Zulu language

| Zulu | |

|---|---|

| isiZulu | |

| Native to | South Africa, Zimbabwe, Lesotho, Malawi, Mozambique, Swaziland |

| Region | KwaZulu-Natal, eastern Gauteng, eastern Free State, southern Mpumalanga |

Native speakers |

12 million (2011 census)[1] L2 speakers: 16 million (2002)[2] |

|

Latin (Zulu alphabet) Zulu Braille | |

| Signed Zulu | |

| Official status | |

Official language in |

|

| Regulated by | Pan South African Language Board |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 |

zu |

| ISO 639-2 |

zul |

| ISO 639-3 |

zul |

| Glottolog |

zulu1248[3] |

S.42[4] | |

| Linguasphere |

99-AUT-fg incl. |

|

Proportion of the South African population that speaks Zulu at home

0–20%

20–40%

40–60%

60–80%

80–100%

| |

| The Zulu Language | |

|---|---|

| Person | umZulu |

| People | amaZulu |

| Language | isiZulu |

| Country | kwaZulu |

Zulu (Zulu: isiZulu) is the language of the Zulu people, with about 10 million speakers, the vast majority (over 95%) of whom live in South Africa. Zulu is the most widely spoken home language in South Africa (24% of the population), and it is understood by over 50% of its population.[5] It became one of South Africa's 11 official languages in 1994.

According to Ethnologue,[6] it is the second most widely spoken of the Bantu languages, after Shona. Like many other Bantu languages, it is written with the Latin alphabet.

In South African English, the language is often referred to by using its native form, isiZulu.

Geographical distribution

Zulu migrant populations have taken it to adjacent regions, especially Zimbabwe, where Zulu is called (Northern) Ndebele.

Xhosa, the predominant language in the Eastern Cape, is often considered mutually intelligible with Zulu.[7]

Maho (2009) lists four dialects: central KwaZulu-Natal Zulu, northern Transvaal Zulu, eastern coastal Qwabe, and western coastal Cele.[4]

History

The Zulu, like Xhosa and other Nguni people, have lived in South Africa for a long time. The Zulu language possesses several click sounds typical of Southern African languages, not found in the rest of Africa. The Nguni people have coexisted with other Southern tribes like the San and Khoi.

Zulu, like most indigenous Southern African languages, was not a written language until the arrival of missionaries from Europe, who documented the language using the Latin script. The first grammar book of the Zulu language was published in Norway in 1850 by the Norwegian missionary Hans Schreuder.[8] The first written document in Zulu was a Bible translation that appeared in 1883. In 1901, John Dube (1871–1946), a Zulu from Natal, created the Ohlange Institute, the first native educational institution in South Africa. He was also the author of Insila kaShaka, the first novel written in Zulu (1930). Another pioneering Zulu writer was Reginald Dhlomo, author of several historical novels of the 19th-century leaders of the Zulu nation: U-Dingane (1936), U-Shaka (1937), U-Mpande (1938), U-Cetshwayo (1952) and U-Dinizulu (1968). Other notable contributors to Zulu literature include Benedict Wallet Vilakazi and, more recently, Oswald Mbuyiseni Mtshali.

The written form of Zulu was controlled by the Zulu Language Board of KwaZulu-Natal. This board has now been disbanded and superseded by the Pan South African Language Board[9] which promotes the use of all eleven official languages of South Africa.

Contemporary usage

English, Dutch and later Afrikaans had been the only official languages used by all South African governments before 1994. However, in the Kwazulu bantustan the Zulu language was widely used. All education in the country at the high-school level was in English or Afrikaans. Since the demise of apartheid in 1994, Zulu has been enjoying a marked revival. Zulu-language television was introduced by the SABC in the early 1980s and it broadcasts news and many shows in Zulu. Zulu radio is very popular and newspapers such as isoLezwe,[10] Ilanga[11] and UmAfrika in the Zulu language are available, mainly available in Kwazulu-Natal province and in Johannesburg. In January 2005 the first full-length feature film in Zulu, Yesterday, was nominated for an Oscar.

South African matriculation requirements no longer specify which South African language needs to be taken as a second language, and some people have made the switch to learning Zulu. However people taking Zulu at high-school level overwhelmingly take it as a first language: according to statistics, Afrikaans is still over 30 times more popular than Zulu as a second language. The mutual intelligibility of many Nguni languages has increased the likelihood of Zulu becoming the lingua franca of the eastern half of the country, although the political dominance of Xhosa-speaking people on national level militates against this. (The predominant language in the Western Cape and Northern Cape is Afrikaans – see the map below.)

In the 1994 film The Lion King, in the "Circle of Life" song, the phrases Ingonyama nengw' enamabala (English: A lion and a leopard spots), Nans' ingonyama bakithi Baba (English: Here comes a lion, Father) and Siyonqoba (English: We will conquer) were used. In some movie songs, like "This Land", the voice says Busa leli zwe bo (Rule this land) and Busa ngothando bo (Rule with love) were used too.

The song Siyahamba is a South African hymn originally written in the Zulu language that became popular in North American churches in the 1990s.

Standard vs urban Zulu

Standard Zulu as it is taught in schools, also called "deep Zulu" (isiZulu esijulile), differs in various respects from the language spoken by people living in cities (urban Zulu, isiZulu sasedolobheni). Standard Zulu tends to be purist, using derivations from Zulu words for new concepts, whereas speakers of urban Zulu use loan words abundantly, mainly from English. For example:

| Standard Zulu | urban Zulu | English |

|---|---|---|

| umakhalekhukhwini | icell | cell/mobile phone |

| Ngiyezwa | Ngiya-andastenda | I understand |

This situation has led to problems in education because standard Zulu is often not understood by young people.[12]

Phonology

Vowels

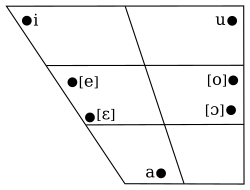

Zulu has a simple vowel system consisting of five vowels.

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i | u | |

| Mid | e | o | |

| Open | a |

/e/ and /o/ are pronounced [e] and [o], respectively, if the following syllable contains an "i" or a "u" or if the vowel is word-final. They are [ɛ] and [ɔ] otherwise:

- umgibeli "passenger", phonetically [úm̩̀ɡìɓé(ː)lì]

- ukupheka "to cook", phonetically [ùɠúpʰɛ̀(ː)ɠà]

There is limited vowel length in Zulu, as a result of the contraction of certain syllables. For example, the word ithambo /íːtʰámbó/ "bone", is a contraction of an earlier ilithambo /ílítʰámbó/, which may still be used by some speakers. Likewise, uphahla /úːpʰaɬa/ "roof" is a contraction of earlier uluphahla /ulúpʰaɬa/. In addition the vowel of the penultimate syllable is allophonically lengthened phrase- or sentence-finally.

Consonants

| Labial | Dental/Alveolar | Postalveolar | Velar | Glottal | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| central | lateral | ||||||

| Click | plain | ǀ | ǁ | ǃ | |||

| aspirated | ǀʰ | ǁʰ | ǃʰ | ||||

| nasalised | ᵑǀ | ᵑǁ | ᵑǃ | ||||

| breathy | ᶢǀʱ | ᶢǁʱ | ᶢǃʱ | ||||

| breathy nasalised | ᵑǀʱ | ᵑǁʱ | ᵑǃʱ | ||||

| Nasal | plain | m | n | ɲ | |||

| breathy | mʱ | nʱ | ɲʱ | ŋ | |||

| Stop | voiceless | p | t | k | |||

| aspirated | pʰ | tʰ | kʰ | ||||

| breathy | b | d | ɡ | ||||

| implosive | ɓ | ɠ | |||||

| Affricate | voiceless | tʃ | kx | ||||

| breathy | dʒ | ||||||

| Fricative | voiceless | f | s | ɬ | ʃ | h | |

| breathy | v | z | ɮ | ɦ | |||

| Approximant | plain | l | j | w | |||

| breathy | jʱ | wʱ | |||||

| Trill | r | ||||||

- The plain voiceless stops and affricates are realised phonetically as ejectives [pʼ], [tʼ], [kʼ], [tʃʼ] [kxʼ].

- When not preceded by a nasal, /ɠ/ is almost in complementary distribution with /k/ and /kʰ/. The latter two phonemes occur almost exclusively root-initial, while /ɠ/ appears exclusively medially. Recent loanwords contain /k/ and /kʰ/ in other positions, e.g. isekhondi /iːsekʰoːndi/ "second", ibhayisikili /iːbajisikiːli/ "bicycle".

- The breathy consonants are depressor consonants. These have a lowering effect on the tone of their syllable. They are only marked with the breathy voice symbol ʱ when the breathiness is contrastive.

- The consonant /ŋ/ occurs as a reduction of the cluster /ŋɡ/, and is therefore always breathy, without being marked as such.

- The trill /r/ is not native to Zulu and occurs only in expressive words and in recent borrowings from European languages.

The use of click consonants is one of the most distinctive features of Zulu. This feature is shared with several other languages of Southern Africa, but it is very rare in other regions. There are three basic articulations of clicks in Zulu:

- Dental /ǀ/, comparable to a sucking of teeth, as the sound one makes for 'tsk tsk'.

- Alveolar /!/, comparable to a bottle top 'pop'.

- Lateral /ǁ/, comparable to a click that one may do for a walking horse.

Each articulation covers five click consonants, with differences such as being voiced, aspirated or nasalised, for a total of 15.

Phonotactics

Zulu syllables are canonically (N)C(w)V, and words must always end in a vowel. Consonant clusters consist of any consonant, optionally preceded by a homorganic nasal consonant (so-called "prenasalisation", described in more detail below) and optionally followed by the consonant /w/.

In addition, syllabic /m̩/ occurs as a reduction of former /mu/, and acts like a true syllable: it can be syllabic even when not word-initial, and can also carry distinctive tones like a full syllable. It does not necessarily have to be homorganic with the following consonant, although the difference between homorganic nonsyllabic /mC/ and syllabic /m̩C/ is distinctive, e.g. umpetshisi /um̩pétʃiːsi/ "peach tree" (5 syllables) versus impoko /ímpoːɠo/ "grass flower" (3 syllables). Moreover, sequences of syllabic m and homorganic m can occur, e.g. ummbila /úm̩mbíːla/ "maize" (4 syllables).

Recent loanwords from languages such as English may violate these constraints, by including additional consonant clusters that are not native to Zulu, such as in igremu /iːgreːmu/ "gram". There may be some variation between speakers as to whether clusters are broken up by an epenthetic vowel or not, e.g. ikhompiyutha /iːkʰompijuːtʰa/ or ikhompyutha /iːkʰompjuːtʰa/ "computer".

Prosody

Stress

Stress in Zulu words is mostly predictable and normally falls on the penultimate syllable of a word. It is accompanied by allophonic lengthening of the vowel. When the final vowel of a word is long due to contraction, it receives the stress instead of the preceding syllable.

Lengthening does not occur on all words in a sentence, however, but only those that are sentence- or phrase-final. Thus, for any word of at least two syllables, there are two different forms, one with penultimate length and one without it, occurring in complementary distribution. In some cases, there are morphemic alternations that occur as a result of word position as well. The remote demonstrative pronouns may appear with the suffix -ana when sentence-final, but only as -ā otherwise. Likewise, the recent past tense of verbs ends in -ile sentence-finally, but is reduced to -ē medially. Moreover, a falling tone can only occur on a long vowel, so the shortening has effects on tone as well.

Some words, such as ideophones or interjections, can have stress that deviates from the regular pattern.

Tone

Like almost all other Bantu and other African languages, Zulu is tonal. There are three main tonemes: low, high and falling. Zulu is conventionally written without any indication of tone, but tone can be distinctive in Zulu. For example, the words for "priest" and "teacher" are both spelled umfundisi, but they are pronounced with different tones: /úm̩fúndisi/ for the "priest" meaning, and /úm̩fundísi/ for the "teacher" meaning.

In principle, every syllable can be pronounced with either a high or a low tone. However, low tone does not behave the same as the other two, as high tones can "spread" into low-toned syllables while the reverse does not occur. A low tone is therefore better described as the absence of any toneme; it is a kind of default tone that is overridden by high or falling tones. The falling tone is a sequence of high-low, and occurs only on long vowels. The penultimate syllable can also bear a falling tone when it is long due to the word's position in the phrase. However, when it shortens, the falling tone becomes disallowed in that position.

In principle, every morpheme has an inherent underlying tone pattern which does not change regardless of where it appears in a word. However, like most other Bantu languages, Zulu has word tone, meaning that the pattern of tones acts more like a template to assign tones to individual syllables, rather than a direct representation of the pronounced tones themselves. Consequently, the relationship between underlying tone patterns and the tones that are actually pronounced can be quite complex. Underlying high tones tend to surface rightward from the syllables where they are underlyingly present, especially in longer words.

Depressor consonants

The breathy consonant phonemes in Zulu are depressor consonants, or depressors for short. Depressor consonants have a lowering effect on pitch, adding a non-phonemic low-tone onset to the normal tone of the syllable. Thus, in syllables with depressor consonants, high tones are realised as rising, and falling tones as rising-then-falling. In both cases, the pitch does not reach as high as in non-depressed syllables. The possible tones on a syllable with a voiceless consonant like hla are [ɬá ɬâ ɬà], and the possible tones of a breathy consonant syllable, like dla, are [ɮǎ̤ ɮa̤᷈ ɮà̤]. A depressor has no effect on a syllable that's already low, but it blocks assimilation to a preceding high tone, so that the tone of the depressor syllable and any following low-tone syllables stays low.

Phonological processes

Prenasalisation

Prenasalisation occurs whenever a consonant is preceded by a homorganic nasal, either lexically or as a consequence of prefixation. The most notable case of the latter is the class 9 noun prefix in-, which ends in a homorganic nasal. Prenasalisation triggers several changes in the following consonant, some of which are phonemic and others allophonic. The changes can be summed as follows:[13][14]

| Normal | Prenasalised | Rule |

|---|---|---|

| /pʰ/, /tʰ/, /kʰ/ | /mp/, /nt/, /ŋk/ | Aspiration is lost on obstruents. |

| /ǀʰ/, /ǁʰ/, /ǃʰ/ | /ᵑǀ/, /ᵑǁ/, /ᵑǃ/ | Aspiration is replaced by nasalisation of clicks. |

| /ǀ/, /ǁ/, /ǃ/ | /ᵑǀʱ/, /ᵑǁʱ/, /ᵑǃʱ/ | Plain clicks become breathy nasal. |

| /ɓ/ | /mb/ | Implosive becomes breathy. |

| /f/, /s/, /ʃ/, /ɬ/ /v/, /z/, /ɮ/ |

[ɱp̪fʼ], [ntsʼ], /ɲtʃ/, [ntɬʼ] [ɱb̪vʱ], [ndzʱ], [ndɮʱ] |

Fricatives become affricates. Only phonemic, and thus reflected orthographically, for /ɲtʃ/. |

| /h/, /ɦ/, /w/, /wʱ/ | [ŋx], [ŋɡʱ], [ŋɡw], [ŋɡwʱ] | Approximants are fortified. This change is allophonic, and not reflected in the orthography. |

| /j/ | /ɲ/ | Palatal approximant becomes palatal nasal. |

| /l/ | /l/ or rarely /nd/ | The outcome /nd/ is a fossilised outcome from the time when /d/ and /l/ were still one phoneme. See Proto-Bantu language. |

| /m/, /n/, ɲ | /m/, /n/, ɲ | No change when the following consonant is itself a nasal. |

Tone assimilation

Zulu has tonic assimilation: high tones tend to spread allophonically to following low-tone syllables, raising their pitch to a level just below that of adjacent high-tone syllables. A toneless syllable between a high-tone syllable and another tonic syllable assimilates to that high tone. That is, if the preceding syllable ends on a high tone and the following syllable begins with a high tone (because it is high or falling), the intermediate toneless syllable has its pitch raised as well. When the preceding syllable is high but the following is toneless, the medial toneless syllable adopts a high-tone onset from the preceding syllable, resulting in a falling tone contour.

For example, the English word spoon was borrowed into Zulu as isipunu, phonemically /ísipúnu/. The second syllable si assimilates to the surrounding high tones, raising its pitch, so that it is pronounced [ísípʼúːnù] sentence-finally. If tone pitch is indicated with numbers, with 1 highest and 9 lowest pitch, then the pitches of each syllable can be denoted as 2-4-3-9.[15] The second syllable is thus still lower in pitch than both of the adjacent syllables.

Tone displacement

Depressor consonants have an effect called tone displacement. Tone displacement occurs whenever a depressor occurs with a high tone, and causes the tone on the syllable to shift rightward onto the next syllable. If the next syllable is long, it gets a falling tone, otherwise a regular high tone. If the penultimate syllable becomes high (not falling), the final syllable dissimilates and becomes low if it wasn't already. Tone displacement is blocked under the following conditions:

- When the syllable has a long vowel.

- When the following syllable also has a depressor consonant.

- When the following syllable is the final syllable, and is short.

Whenever tone displacement is blocked, this results in a depressor syllable with high tone, which will have the low-tone onset as described above. When the following syllable already has a high or falling tone, the tone disappears from the syllable as if it had been shifted away, but the following syllable's tone is not modified.

Some examples:

- izipunu "spoons", the plural of isipunu from the previous section, is phonemically /ízipúnu/. Because /z/ is a depressor consonant, tone assimilation is prevented. Consequently, the word is pronounced as [ízìpʼúːnù] sentence-finally, with low tone in the second syllable.

- izintombi "girls" is phonemically /izíntombí/. /z/ is a depressor, and is not blocked, so the tone shifts to the third syllable. This syllable can be either long or short depending on sentence position. When long, the pronunciation is [ìzìntômbí], with a falling tone. However, when the third syllable is short, the tone is high, and dissimilation of the final syllable occurs, resulting in [ìzìntómbì].

- nendoda "with a man" is phonemically /nʱéndoda/. /nʱ/ is a depressor, but so is /d/, so tone displacement is blocked. Consequently, the pronunciation is [nʱěndɔ̀ːdà], with rising pitch in the first syllable due to the low-onset effect.

Palatalisation

Palatalisation is a change that affects labial and alveolar consonants whenever they are immediately followed by /j/. While palatalisation occurred historically, it is still productive, and occurs as a result of the addition of suffixes beginning with /j/. A frequent example is the diminutive suffix -yana.

Moreover, Zulu does not generally tolerate sequences of a labial consonant plus /w/. Whenever /w/ follows a labial consonant, it changes to /j/, which then triggers palatalisation of the consonant. This effect can be seen in the locative forms of nouns ending in -o or -u, which changes to -weni and -wini respectively in the locative. If a labial consonant immediately precedes, palatalisation is triggered. The change also occurs in nouns beginning in ubu- with a stem beginning with a vowel.

The following changes occur as a result of palatalisation:

| Original consonant |

Palatalised consonant |

Examples |

|---|---|---|

| pʰ | ʃ |

|

| tʰ |

| |

| p | tʃ |

|

| t |

| |

| ɓ |

| |

| b | dʒ |

|

| d |

| |

| m | ɲ |

|

| n |

| |

| mp | ɲtʃ |

|

| nt |

| |

| mb | ɲdʒ |

|

| nd |

|

Orthography

Zulu employs the 26 letters of the ISO basic Latin alphabet. However, some of the letters have different pronunciation than in English. Additional phonemes are written using sequences of multiple letters. Tone, stress and vowel length are not indicated.

| Letter(s) | Phoneme(s) | Example |

|---|---|---|

| a | /a/ | amanzi /amaːnzi/ "water" |

| b | /ɓ/ | ubaba /uɓaːɓa/ "my/our father" |

| bh | /b/ | ukubhala /uɠubaːla/ "to write" |

| c | /ǀ/ | icici /iːǀiːǀi/ "earring" |

| ch | /ǀʰ/ | ukuchaza /uɠuǀʰaːza/ "to fascinate/explain" |

| d | /d/ | idada /iːdaːda/ "duck" |

| dl | /ɮ/ | ukudla /uɠuːɮa/ "to eat" |

| e | /e/ | ibele /iːɓeːle/ "breast" |

| f | /f/ | ifu /iːfu/ "cloud" |

| g | /ɡ/ | ugogo /uɡoːɡo/ "grandmother" |

| gc | /ᶢǀʱ/ | isigcino /isiᶢǀʱiːno/ "end" |

| gq | /ᶢǃʱ/ | uMgqibelo /um̩ᶢǃʱiɓeːlo/ "Saturday" |

| gx | /ᶢǁʱ/ | ukugxoba /uɠuᶢǁʱoːɓa/ "to stamp" |

| h | /h/ | ukuhamba /uɠuhaːmba/ "to go" |

| hh | /ɦ/ | ihhashi /iːɦaːʃi/ "horse" |

| hl | /ɬ/ | ukuhlala /uɠuɬaːla/ "to sit" |

| i | /i/ | imini /imiːni/ "daytime" |

| j | /dʒ/ | uju /uːdʒu/ "honey" |

| k | /k/ | ikati /iːkaːti/ "cat" |

| /ɠ/ | ukuza /uɠuːza/ "to come" | |

| kh | /kʰ/ | ikhanda /iːkʰaːnda/ "head" |

| kl | /kx/ | umklomelo /um̩kxomeːlo/ "prize" |

| l | /l/ | ukulala /uɠulaːla/ "sleep" |

| m | /m/ | imali /imaːli/ "money" |

| /mʱ/ | umama /umʱaːma/ "my/our mother" | |

| mb | /mb/ | imbube /imbuːɓe/ "lion" |

| n | /n/ | unina /uniːna/ "his/her/their mother" |

| /nʱ/ | nendoda /nʱendoːda/ "with a man" | |

| nc | /ᵑǀ/ | incwancwa /iᵑǀwaːᵑǀwa/ "sour corn meal" |

| ng | /ŋ/ | ingane /iŋɡaːne/ "child" |

| ngc | /ᵑǀʱ/ | ingcosi /iᵑǀʱoːsi/ "a bit" |

| ngq | /ᵑǃʱ/ | ingqondo /iᵑǃʱoːndo/ "brain" |

| ngx | /ᵑǁʱ/ | ingxenye /iᵑǁʱeːɲe/ "part" |

| nj | /ɲdʒ/ | inja /iːɲdʒa/ "dog" |

| nk | /ŋk/ | inkomo /iŋkoːmo/ "cow" |

| nq | /ᵑǃ/ | inqola /iᵑǃoːla/ "cart" |

| ntsh | /ɲtʃ/ | intshe /iːɲtʃe/ "ostrich" |

| nx | /ᵑǁ/ | inxeba /iᵑǁeːɓa/ "wound" |

| ny | /ɲ/ | inyoni /iɲoːni/ "bird" |

| /ɲʱ/ | ||

| o | /o/ | uphondo /uːpʰoːndo/ "horn" |

| p | /p/ | ipipi /iːpiːpi/ "pipe for smoking" |

| ph | /pʰ/ | ukupheka /uɠupʰeːɠa/ "to cook" |

| q | /ǃ/ | iqaqa /iːǃaːǃa/ "polecat" |

| qh | /ǃʰ/ | iqhude /iːǃʰuːde/ "rooster" |

| r | /r/ | iresiphi /iːresiːpʰi/ "recipe" |

| s | /s/ | isisu /iːsiːsu/ "stomach" |

| sh | /ʃ/ | ishumi /iːʃuːmi/ "ten" |

| t | /t/ | itiye /iːtiːje/ "tea" |

| th | /tʰ/ | ukuthatha /uɠutʰaːtʰa/ "to take" |

| tsh | /tʃ/ | utshani /utʃaːni/ "grass" |

| u | /u/ | ubusuku /uɓusuːɠu/ "night" |

| v | /v/ | ukuvala /uɠuvaːla/ "to close" |

| w | /w/ | ukuwela /uɠuweːla/ "to cross" |

| /wʱ/ | wuthando /wʱuːtʰaːndo/ "It's love." | |

| x | /ǁ/ | ixoxo /iːǁoːǁo/ "frog" |

| xh | /ǁʰ/ | ukuxhasa /uɠuǁʰaːsa/ "to support" |

| y | /j/ | uyise /ujiːse/ "his/her/their father" |

| /jʱ/ | yintombazane /jʱintombazaːne/ "It's a girl" | |

| z | /z/ | umzuzu /um̩zuːzu/ "moment" |

Reference works and older texts may use additional letters. A common former practice was to indicate the implosive /ɓ/ using the special letter ɓ, while the digraph bh would then be simply written as b. Some references may also write h after letters to indicate that they are of the depressor variety, e.g. mh, nh, yh, a practice that is standard in Xhosa orthography.

Very early texts, from the early 20th century or before, tend to omit the distinction between plain and aspirated voiceless consonants, writing the latter without the h.

Nouns are written with their prefixes as one orthographical word. If the prefix ends with a vowel (as most do) and the noun stem also begins with a vowel, a hyphen is inserted in between, e.g. i-Afrika. This occurs only with loanwords.

Morphology

Here are some of the main features of Zulu:

- Word order is subject–verb–object.

- Morphologically, it is an agglutinative language.

- As in other Bantu languages, Zulu nouns are classified into morphological classes or genders (16 in Zulu), with different prefixes for singular and plural. Various parts of speech that qualify a noun must agree with the noun according to its gender. Such agreements usually reflect part of the original class with which it is agreeing. An example is the use of the class 'aba-':

- Bonke abantu abaqatha basepulazini bayagawula.

- All the strong people of the farm are felling (trees).

- The various agreements that qualify the word 'abantu' (people) can be seen in effect.

- Its verbal system shows a combination of temporal and aspectual categories in their finite paradigm. Typically verbs have two stems, one for present-undefinite and another for perfect. Different prefixes can be attached to these verbal stems to specify subject agreement and various degrees of past or future tense. For example, in the word uyathanda ("he loves"), the present stem of the verb is -thanda, the prefix u- expresses third-person singular subject and -ya- is a filler that is used in short sentences.

- Suffixes are also put into common use to show the causative or reciprocal forms of a verb stem.

- Most property words (words encoded as adjectives in English) are represented by relative. In the sentence umuntu ubomvu ("the person is red"), the word ubomvu (root -bomvu) behaves like a verb and uses the agreement prefix u-. however, there are subtle differences; for example, it does not use the prefix ya-.

Morphology of root Zulu

The root can be combined with a number of prefixes and thus create other words. For example, here is a table with a number of words constructed from the roots -Zulu and -ntu (the root for person/s, people):

| Prefix | -zulu | -ntu |

|---|---|---|

| um(u) | umZulu (a Zulu person) | umuntu (a person) |

| ama, aba | amaZulu (Zulu people) | abantu (people) |

| isi | isiZulu (the Zulu language) | isintu (culture, heritage, mankind) |

| ubu | ubuZulu (personification/Zulu-like tendencies) | ubuntu (humanity, compassion) |

| kwa | kwaZulu (place of the Zulu people) | – |

| i(li) | izulu (the weather/sky/heaven) | – |

| pha | phezulu (on top) | – |

| e | ezulwini (in, at, to, from heaven) | – |

Sample phrases and text

The following is a list of phrases that can be used when one visits a region whose primary language is Zulu:

| Sawubona | Hello, to one person |

| Sanibonani | Hello, to a group of people |

| Unjani? / Ninjani? | How are you (sing.)? / How are you (pl.)? |

| Ngiyaphila / Siyaphila | I'm okay / We're okay |

| Ngiyabonga (kakhulu) | Thanks (a lot) |

| Ngubani igama lakho? | What is your name? |

| Igama lami ngu... | My name is... |

| Isikhathi sithini? | What's the time? |

| Ngingakusiza? | Can I help you? |

| Uhlala kuphi? | Where do you stay? |

| Uphumaphi? | Where are you from? |

| Hamba kahle / Sala kahle | Go well / Stay well, used as goodbye. The person staying says "Hamba kahle", and the person leaving says "Sala kahle". Other translations include Go gently and Walk in peace.[16] |

| Hambani kahle / Salani kahle | Go well / Stay well, to a group of people |

| Eish! | Wow! (No real European equivalent, used in South African English) (you could try a semi-expletive, such as oh my God or what the heck. It expresses a notion of shock and surprise) |

| Hhayibo | No! / Stop! / No way! (used in South African English too) |

| Yebo | Yes |

| Cha | No |

| Angazi | I don't know |

| Ukhuluma isiNgisi na? | Do you speak English? |

| Ngisaqala ukufunda isiZulu | I've just started learning Zulu |

| Uqonde ukuthini? | What do you mean? |

| Ngiyakuthanda. | "I love you." |

The following is from the preamble to the Constitution of South Africa:

Thina, bantu baseNingizimu Afrika, Siyakukhumbula ukucekelwa phansi kwamalungelo okwenzeka eminyakeni eyadlula; Sibungaza labo abahluphekela ubulungiswa nenkululeko kulo mhlaba wethu; Sihlonipha labo abasebenzela ukwakha nokuthuthukisa izwe lethu; futhi Sikholelwa ekutheni iNingizimu Afrika ingeyabo bonke abahlala kuyo, sibumbene nakuba singafani.

Translation:

We, the people of South Africa, Recognize the injustices of our past; Honor those who suffered for justice and freedom in our land; Respect those who have worked to build and develop our country; and Believe that South Africa belongs to all who live in it, united in our diversity.

Zulu words in South African English

South African English has absorbed many words from the Zulu language. Others, such as the names of local animals (impala and mamba are both Zulu names) have made their way into standard English. A few examples of Zulu words used in South African English:

- muti (from umuthi) – medicine

- donga (from udonga) – ditch (udonga means 'wall' in Zulu and is also the name for ditches caused by soil erosion)

- indaba – conference (it means 'an item of news' in Zulu)

- induna – chief or leader

- shongololo (from ishongololo) – millipede

- ubuntu – compassion/humanity.

See also

- Bantu language

- Impi

- Nguni culture

- Shaka kaSenzangakhona

- Tsotsitaal – a Zulu-based creole language spoken in Soweto

- UCLA Language Materials Project

- Zulu people

Sources

References

- ↑ Zulu at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015)

- ↑ Webb, Vic. 2002. "Language in South Africa: the role of language in national transformation, reconstruction and development." Impact: Studies in language and society, 14:78

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin; Bank, Sebastian, eds. (2016). "Zulu". Glottolog 2.7. Jena: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- 1 2 Jouni Filip Maho, 2009. New Updated Guthrie List Online

- ↑ Ethnologue 2005

- ↑ Ethnologue's Shona entry

- ↑ Spiegler, Sebastian; van der Spuy, Andrew; Flach, Peter A. (August 2010). "Ukwabelana - An open-source morphological Zulu corpus". Proceedings of the 23rd International Conference on Computational Linguistics. Beijing, China: Tsinghua University Press. p. 1020.

- ↑ Rakkenes, Øystein (2003) Himmelfolket: En Norsk Høvding i Zululand, Oslo: Cappelen Forlag, pp. 63–65

- ↑ pansalb.org.za

- ↑ isolezwe.co.za

- ↑ ilanganews.co.za

- ↑ Magagula, Constance Samukelisiwe (2009). Standard Versus Non-standard IsiZulu: A Comparative Study Between Urban and Rural Learners' Performance and Attitude. Durban: University of KwaZulu-Natal.

- ↑ Rycroft & Ngcobo (1979) Say it in Zulu, p. 6

- ↑ Zulu-English dictionary, C.M. Doke & B.W. Vilakazi

- ↑ Zulu-English Dictionary, Doke, 1958

- ↑ Zulu English Dictionary

Bibliography

- Canonici, Noverino, 1996, Imisindo YesiZulu: An Introduction to Zulu Phonology, University of Natal

- Canonici, Noverino, 1996, Zulu Grammatical Structure, University of Natal

- Wade, Rodrik D. (1996). "Structural characteristics of Zulu English". An Investigation of the Putative Restandardisation of South African English in the Direction of a 'New' English, Black South African English (Thesis). Durban: University of Natal. Archived from the original on 13 October 2008.

Further reading

- Colenso, John William (1882). First steps in Zulu: being an elementary grammar of the Zulu language (Third ed.). Martizburg, Durban: Davis.

- Dent, G.R. and Nyembezi, C.L.S. (1959) Compact Zulu Dictionary. Pietermaritzburg: Shuter & Shooter. ISBN 0-7960-0760-8

- Dent, G.R. and Nyembezi, C.L.S. (1969) Scholar's Zulu Dictionary. Pietermaritzburg: Shuter & Shooter. ISBN 0-7960-0718-7

- Doke, C.M. (1947) Text-book of Zulu grammar. London: Longmans, Green and Co.

- Doke, C.M. (1953) Zulu–English Dictionary. Johannesburg: Witwatersrand University Press. ISBN 1-86814-160-8

- Doke, C.M. (1958) Zulu–English Vocabulary. Johannesburg: Witwatersrand University Press. ISBN 0-85494-009-X

- Nyembezi, C.L.S. (1957) Learn Zulu. Pietermaritzburg: Shuter & Shooter. ISBN 0-7960-0237-1

- Nyembezi, C.L.S. (1970) Learn More Zulu. Pietermaritzburg: Shuter & Shooter. ISBN 0-7960-0278-9

- Wilkes, Arnett, Teach Yourself Zulu. ISBN 0-07-143442-9

External links

| Zulu edition of Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia |

| Wikibooks has a book on the topic of: Zulu |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Zulu phrasebook. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Zulu language. |

- Dryer, Matthew S. & Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2013). "Zulu". World Atlas of Language Structures Online. Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.

- The Universal Declaration of Human Rights in Zulu

- South African Languages: IsiZulu

- A short English–isiZulu–Japanese phraselist incl. sound file

- Zulu Swadesh list of basic vocabulary words (from Wiktionary's Swadesh-list appendix)

- Counting in Zulu

Courses

- Zulu With Dingani - Online beginner's course

- University Of South Africa, free online course

- Sifunda isiZulu!

Grammar

Dictionaries

Newspapers

- Isolezwe

- Ilanga

- UmAfrika

- Izindaba News24

Software

- Spell checker for OpenOffice.org and Mozilla, OpenOffice.org, Mozilla Firefox web-browser, and Mozilla Thunderbird email program in Zulu

- Translate.org.za Project to translate Free and Open Source Software into all the official languages of South Africa including Zulu

- PanAfrican L10n wiki page on Zulu