Zhao (state)

| State of Zhao | ||||||||||

| 趙 | ||||||||||

| Kingdom | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

| Capital | Jinyang, Handan | |||||||||

| Religion | Chinese folk religion ancestor worship | |||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | |||||||||

| Historical era | Warring States period | |||||||||

| • | Partition of Jin | 403 BC | ||||||||

| • | Conquered by Qin | 222 BC | ||||||||

| Currency | spade money other ancient Chinese coinage | |||||||||

| ||||||||||

| Zhao | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

"Zhao" in seal script (top), Traditional (middle), and Simplified (bottom) Chinese characters | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 趙 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 赵 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

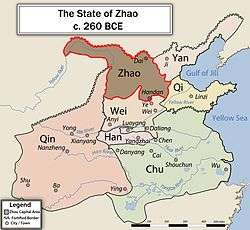

Zhao (Chinese: 趙) was one of the seven major states during the Warring States period of ancient China. It was created from the three-way Partition of Jin, together with Han and Wei, in the 5th century BC. Zhao gained significant strength from the military reforms initiated during King Wuling's reign, but suffered a crushing defeat at the hands of Qin at the Battle of Changping. Its territory included areas now in modern Inner Mongolia, Hebei, Shanxi and Shaanxi provinces. It bordered the Xiongnu, the states of Qin, Wei and Yan. Its capital was Handan, in modern Hebei Province.

Zhao was home to administrative philosopher Shen Dao, sophist Gongsun Long and the Confucian Xun Kuang.[1]

Origins and ascendancy

At the end of the Spring and Autumn Period, the state of Jin was divided up between three powerful ministers; the Zhao family patriarch being one of them. In 403 BC, the king of Zhou formally recognized the existence of the State of Zhao along with two other States, Han and Wei, marking the start of the Warring States Period.

At the onset of the Warring States period, Zhao was one of the weaker states. Despite its extensive territory, its northern border was frequently subject to harassment by the Xiongnu and by other northern nomadic peoples. At the same time, Zhao was surrounded by strong states and lacked the military strength of Wei or the prosperity of Qi. Zhao became a pawn in the struggle between the states of Wei and Qi, and this struggle came to a climax in 354 BC when Wei invaded Zhao, and Zhao had to seek aid from Qi. The resulting Battle of Guiling was a major victory for Qi, and it consequently lessened the threat to Zhao's southern border.

Zhao remained relatively weak until the military reforms of King Wuling of Zhao (325-299 BC). The soldiers of Zhao were ordered to dress like their Xiongnu neighbours and to replace war chariots with cavalry archers. This reform proved to be a brilliant strategy. With the advanced technology of the Chinese states and nomadic tactics, the cavalry of Zhao became a powerful force. The result was that the newly strengthened Zhao was evenly matched against its greatest enemy, the state of Qi.

Zhao demonstrated its enhanced military prowess by conquering the State of Zhongshan in 295 BC after a prolonged war, and annexing territory from its neighbouring states of Wei, Yan, and Qin. During this time, the cavalry of Zhao also occasionally intruded into the state of Qi in campaigns against the state of Chu.

Several brilliant military commanders of the period appeared concurrently, including Lian Po, Zhao She (趙奢) and Li Mu. Lian Po proved instrumental in defending Zhao against the Qin. Zhao She was most active in the east; leading the invasion of the Yan state. Li Mu defended Zhao from the Xiongnu and later from Qin.

Fall of Zhao

By the end of the Warring States Period, Zhao was the only state strong enough to oppose the powerful Qin state. An alliance with Wei against Qin commenced in 287 BC but ended in defeat at Huayang in 273 BC. The struggle then culminated in the bloodiest battle of the whole period, the Battle of Changping in 260 BC. The troops of Zhao were completely defeated by Qin. Although the forces of Wei and Chu saved Handan from a follow-up siege by the victorious Qin, Zhao would never recover from the enormous loss of men in the battle.

In 229 BC, invasions led by the Qin general Wang Jian were opposed by Li Mu and his subordinate officer Sima Shang (司馬尚) until 228 BC. According to some accounts, King Youmiu, ordered the execution of Li Mu and relieved Sima Shang from his duties, due to faulty advice from disloyal court officials and Qin infiltrators.

In 228 BC, Qin captured King Youmiu and conquered Zhao. Prince Jia, the stepbrother of King Qian, was proclaimed King Jia at Dai and led the last Zhao forces against the Qin. The regime lasted until 222 BC, when the Qin army captured him and defeated his forces at Dai.

In 154 BC, an unrelated Zhao (赵), headed by Liu Sui (劉遂), the Prince of Zhao kingdom, participated in the unsuccessful Rebellion of the Seven States (Chinese: 七国之乱) against the newly installed second emperor of the Han dynasty.

Culture and society

Before Qin unified China, each state had its own customs and culture. According to the Yu Gong or Tribute of Yu, composed in the 4th or 5th century BC and included in the Book of Documents, there were nine distinct cultural regions of China, which are described in detail in this book. The work focuses on the travels of the titular sage, Yu the Great, throughout each of the regions. Other texts, predominantly military, also discussed these cultural variations.[2]

One of these texts was The Book of Master Wu, written in response to a query by Marquis Wu of Wei on how to cope with the other states. Wu Qi, the author of the work, declared that the government and nature of the people were reflective of the terrain they live in. Of Zhao, he said:

The two states of Han and Zhao train their troops rigorously but have difficulty in applying their skills to the battlefield.— Wuzi, Master Wu

Han and Zhao are states of the Central Plain. Theirs are a gentle people, weary from war and experienced in arms, but have little regard for their generals. The soldiers' salaries are meager and their officers have no strong commitment to their countries. Although their troops are experienced, they cannot be expected to fight to the death. To defeat them, we must concentrate large numbers of troops in our attacks to present them with certain peril. When they counterattack, we must be prepared to defend our positions vigorously and make them pay dearly. When they retreat, we must pursue and give them no rest. This will grind them down.— Wuzi, Master Wu

List of Zhao rulers

- Marquess Xian (獻侯), personal name Huan (浣), ruled 424 BC–409 BC

- Marquess Lie (烈侯), personal name Ji (籍), son of previous, ruled 409 BC–387 BC, noted for several reforms

- Marquess Jing (敬侯), personal name Zhang (章), son of previous, ruled 387 BC–375 BC

- Marquess Cheng (成侯), personal name Zhong (種), son of previous, ruled 375 BC–350 BC

- Marquess Su (肅侯), personal name Yu (語), son of previous, ruled 350 BC–326 BC

- King Wuling (武靈王), personal name Yong (雍), son of previous, ruled 326 BC–Spring 299 BC

- King Huiwen (惠文王), personal name He (何), son of previous, ruled Spring 299 BC–266 BC

- King Xiaocheng (孝成王), personal name Dan (丹), son of previous, ruled 266 BC–245 BC

- King Daoxiang (悼襄王), personal name Yan (偃), son of previous, ruled 245 BC–236 BC

- King Youmiu (幽繆王), personal name Qian (遷), son of previous, ruled 236 BC–228 BC

- King Jia of Dai (代王), personal name Jia (嘉), half-brother of previous, ruled 228 BC–222 BC

Zhao in astronomy

There is two opinions about the representing star of Zhao in Chinese astronomy. The opinions are :

- Zhao is represented with the star Lambda Herculis in asterism Left Wall, Heavenly Market enclosure .,[3] and also represented with two stars 26 Capricorni (趙一 Zhao yī, English: the First Star of Zhao) and 27 Capricorni (趙二 Zhao èr, English: the Second Star of Zhao) in asterism Twelve States, Girl mansion.[4] (see Chinese constellation).

- Zhao is represented with the star Lambda Herculis,[5] and also represented with star "m Capricorni".[6]

See also

- The kingdoms of Former Zhao and Later Zhao of the Sixteen Kingdoms

References

- ↑ Huang Kejian 2010 p.185. From Destiny to Dao: A Survey of Pre-Qin Philosophy in China. https://books.google.com/books?id=bATIDgAAQBAJ&pg=PA185

- ↑ Lewis 2007, p. 12

- ↑ (in Chinese) AEEA (Activities of Exhibition and Education in Astronomy) 天文教育資訊網 2006 年 6 月 23 日

- ↑ zh:北方中西星名對照表

- ↑ Richard Hinckley Allen: Star Names – Their Lore and Meaning: Hercules

- ↑ Richard Hinckley Allen: Star Names – Their Lore and Meaning: Capricornus

.svg.png)