Benzalkonium chloride

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Other names

N-Alkyl-N-benzyl-N,N-dimethylammonium chloride; Alkyldimethylbenzylammonium chloride; ADBAC; BC50 BC80; Quaternary ammonium compounds; quats | |

| Identifiers | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.058.301 |

| EC Number | 264-151-6 |

| KEGG | |

| RTECS number | BO3150000 |

| UNII | |

| Properties | |

| variable | |

| Molar mass | variable |

| Appearance | 100% is white or yellow powder; gelatinous lumps; Solutions BC50 (50%) & BC80 (80%) are colorless to pale yellow solutions |

| Density | 0.98 g/cm3 |

| very soluble | |

| Pharmacology | |

| D08AJ01 (WHO) | |

| Hazards | |

| EU classification (DSD) (outdated) |

C, N [1] |

| R-phrases (outdated) | R21/22, R34, R50 [1] |

| S-phrases (outdated) | (S2), S36/37/39, S45, S61 [1] |

| NFPA 704 | |

| Flash point | 250 °C (482 °F; 523 K) (if solvent based) |

| Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| | |

| Infobox references | |

Benzalkonium chloride, also known as BZK, BKC, BAC, alkyldimethylbenzylammonium chloride and ADBAC, is a type of cationic surfactant. It is an organic salt classified as a quaternary ammonium compound. It has three main categories of use: as a biocide, a cationic surfactant, and as a phase transfer agent.[2] ADBACs are a mixture of alkylbenzyldimethylammonium chlorides, in which the alkyl group has various even-numbered alkyl chain lengths.

Solubility and physical properties

Depending on purity, benzalkonium chloride ranges from colourless to a pale yellow (impure). Benzalkonium chloride is readily soluble in ethanol and acetone. Although dissolution in water is slow, aqueous solutions are easier to handle and are preferred. Aqueous solutions should be neutral to slightly alkaline. Solutions foam when shaken. Concentrated solutions have a bitter taste and a faint almond-like odour.

Standard concentrates are manufactured as 50% and 80% w/w solutions, and sold under trade names such as BC50, BC80, BAC50, BAC80, etc. The 50% solution is purely aqueous, while more concentrated solutions require incorporation of rheology modifiers (alcohols, polyethylene glycols, etc.) to prevent increases in viscosity or gel formation under low temperature conditions.

Cationic surfactant

Benzalkonium chloride also possesses surfactant properties, dissolving the lipid phase of the tear film and increasing drug penetration, making it a useful excipient.[3]

- Laundry detergents and treatments

- Softeners for textiles

Phase transfer agent

Benzalkonium chloride is a mainstay of phase-transfer catalysis, an important technology in the synthesis of organic compounds, including drugs.

Bioactive agents

Especially for their antimicrobial activity, benzalkonium chloride is an active ingredient in many consumer products:

- Pharmaceutical products such as eye, ear and nasal drops or sprays, as a preservative

- Personal care products such as hand sanitizers, wet wipes, shampoos, deodorants and cosmetics

- Skin antiseptics, such as Bactine and Dettol

- Some disinfectant solutions, such as post-piercing ear disinfectants.

- Throat lozenges[4] and mouthwashes, as a biocide

- Spermicidal creams

- Over-the-counter single-application treatments for herpes, cold-sores, and fever blisters, such as RELEEV and Viroxyn

- Burn and ulcer treatment

- Spray disinfectants for hard surface sanitization

- Cleaners for floor and hard surfaces as a disinfectant, such as Lysol

- Algaecides for clearing of algae, moss, lichens from paths, roof tiles, swimming pools, masonry, etc.

Benzalkonium chloride is also used in many non-consumer processes and products, including as an active ingredient in surgical disinfection. A comprehensive list of uses includes industrial applications.[5] An advantage of benzalkonium chloride, not shared by ethanol-based antiseptics or hydrogen peroxide antiseptic, is that it does not cause a burning sensation when applied to broken skin.,

Medicine

Benzalkonium chloride is a frequently used preservative in eye drops; typical concentrations range from 0.004% to 0.01%. Stronger concentrations can be caustic[6] and cause irreversible damage to the corneal endothelium.[7]

Avoiding the use of benzalkonium chloride solutions while contact lenses are in place is discussed in the literature.[8][9]

Adverse effects

Although historically benzalkonium chloride has been ubiquitous as a preservative in ophthalmic preparations, its ocular toxicity and irritant properties,[10] in conjunction with consumer demand, have led pharmaceutical companies to increase production of preservative-free preparations, or to replace benzalkonium chloride with preservatives which are less harmful.

Many mass-marketed inhaler and nasal spray formulations contain benzalkonium chloride as a preservative, despite substantial evidence that it can adversely affect ciliary motion, mucociliary transport, nasal mucosal histology, human neutrophil function, and leukocyte response to local inflammation.[11] Although some studies have found no correlation between use of benzalkonium chloride in concentrations at or below 0.1% in nasal sprays and drug-induced rhinitis,[12] others have recommended that benzalkonium chloride in nasal sprays is avoided.[13][14] In the United States, nasal steroid preparations that are free of benzalkonium chloride include budesonide, triamcinolone acetonide, dexamethasone, and Beconase and Vancenase aerosol inhalers.[11]

Benzalkonium chloride is irritant to middle ear tissues at typically used concentrations. Inner ear toxicity has been demonstrated.[15]

Occupational exposure to benzalkonium chloride has been linked to the development of asthma.[16] In 2011, a large clinical trial designed to evaluate the efficacy of hand sanitizers based on different active ingredients in preventing virus transmission amongst schoolchildren was re-designed to exclude sanitizers based on benzalkonium chloride due to safety concerns.[17]

Benzalkonium chloride has been in common use as a pharmaceutical preservative and antimicrobial since the 1940s. While early studies confirmed the corrosive and irritant properties of benzalkonium chloride, investigations into the adverse effects of, and disease states linked to, benzalkonium chloride have only surfaced during the past 30 years.

Benzalkonium chloride is classed as a Category III antiseptic active ingredient by the United States Food and Drug Administration. Ingredients are categorised as Category III when "available data are insufficient to classify as safe and effective, and further testing is required”. Benzalkonium chloride is excluded from the current United States Food and Drug Administration review of the safety and effectiveness of consumer antiseptics and topical antimicrobial over-the-counter drug products, meaning it will remain a Category III ingredient.[18] There is acknowledgement that more data are required on its safety, efficacy and effectiveness, especially with relation to:

- Human pharmacokinetic studies, including information on its metabolites

- Studies on animal absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion

- Data to help define the effect of formulation on dermal absorption

- Carcinogenicity

- Studies on developmental and reproductive toxicology

- Potential hormonal effects

- Assessment of the potential for development of bacterial resistance

Toxicology

RTECS lists the following acute toxicity data:[19]

| Organism | Route of exposure | Dose (LD50) |

|---|---|---|

| Rat | Intravenous | 13.9 mg/kg |

| Rat | Oral | 240 mg/kg |

| Rat | Intraperitoneal | 14.5 mg/kg |

| Rat | Subcutaneous | 400 mg/kg |

| Mouse | Subcutaneous | 64 mg/kg |

Benzalkonium chloride is a human skin and severe eye irritant.[20] It is a suspected respiratory toxicant, immunotoxicant, gastrointestinal toxicant and neurotoxicant.[21][22][23]

Benzalkonium chloride formulations for consumer use are dilute solutions. Concentrated solutions are toxic to humans, causing corrosion/irritation to the skin and mucosa, and death if taken internally in sufficient volumes. 0.1% is the maximum concentration of benzalkonium chloride that does not produce primary irritation on intact skin or act as a sensitizer.[24]

Poisoning by benzalkonium chloride is recognised in the literature.[25] A 2014 case study detailing the fatal ingestion of up to 240ml of 10% benzalkonium chloride in a 78-year-old male also includes a summary of the currently published case reports of benzalkonium chloride ingestion. While the majority of cases were caused by confusion about the contents of containers, one case cites incorrect pharmacy dilution of benzalkonium chloride as the cause of poisoning of two infants.[26]

Benzalkonium chloride poisoning of domestic pets has been recognised as a result of direct contact with surfaces cleaned with disinfectants utilising benzalkonium chloride as an active ingredient.[27]

Biological activity

The greatest biocidal activity is associated with the C12 dodecyl & C14 myristyl alkyl derivatives. The mechanism of bactericidal/microbicidal action is thought to be due to disruption of intermolecular interactions. This can cause dissociation of cellular membrane lipid bilayers, which compromises cellular permeability controls and induces leakage of cellular contents. Other biomolecular complexes within the bacterial cell can also undergo dissociation. Enzymes, which finely control a wide range of respiratory and metabolic cellular activities, are particularly susceptible to deactivation. Critical intermolecular interactions and tertiary structures in such highly specific biochemical systems can be readily disrupted by cationic surfactants.

Benzalkonium chloride solutions are fast-acting biocidal agents with a moderately long duration of action. They are active against bacteria and some viruses, fungi, and protozoa. Bacterial spores are considered to be resistant. Solutions are bacteriostatic or bactericidal according to their concentration. Gram-positive bacteria are generally more susceptible than gram-negative bacteria. Activity is not greatly affected by pH, but increases substantially at higher temperatures and prolonged exposure times.

In a 1998 study utilizing the FDA protocol, a non-alcohol sanitizer with benzalkonium chloride as the active ingredient met the FDA performance standards, while Purell, a popular alcohol-based sanitizer, did not. The study, which was undertaken and reported by a leading US developer, manufacturer and marketer of topical antimicrobial pharmaceuticals based on quaternary ammonium compounds, found that their own benzalkonium chloride-based sanitizer performed better than alcohol-based hand sanitizer after repeated use.[28]

Advancements in the quality and efficacy of benzalkonium chloride in current non-alcohol hand sanitizers has addressed the CDC concerns regarding gram negative bacteria, with the leading products being equal if not more effective against gram negative, particularly New Delhi metallo-beta-lactamase 1 and other antibiotic resistant bacteria.

Newer formulations using benzalkonium blended with various quaternary ammonium derivatives can be used to extend the biocidal spectrum and enhance the efficacy of benzalkonium based disinfection products. Formulation techniques have been used to great effect in enhancing the virucidal activity of quaternary ammonium-based disinfectants such as Virucide 100 to typical healthcare infection hazards such as hepatitis and HIV. The use of appropriate excipients can also greatly enhance the spectrum, performance and detergency, and prevent deactivation under use conditions. Formulation can also help minimise deactivation of benzalkonium solutions in the presence of organic and inorganic contamination.

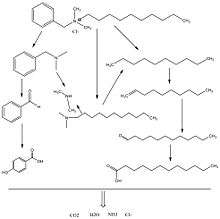

Degradation

Benzalkonium chloride degradation follows consecutive debenzylation, dealkylation, and demethylation steps producing benzyl chloride, alkyl dimethyl amine, dimethyl amine, long chain alkane, and ammonia.[29] The intermediates, major, and minor products can then be broken down into CO2, H2O, NH3, and Cl-. The first step to the biodegradation of BAC is the fission or splitting of the alkyl chain from the quaternary nitrogen as shown in the diagram. This is done by abstracting the hydrogen from the alkyl chain by using a hydroxyl radical leading to a carbon centered radical. This results in benzyl dimethyl amine as the first intermediate and dodecanal as the major product.[29] From here, benzyl dimethyl amine can be oxidized to benzoic acid using the Fenton process. The trimethyl amine group in dimethylbenzylamine can be cleaved to form a benzyl that can be further oxidized to benzoic acid. Benzoic acid uses hydroxylation (adding a hydroxyl group) to form p-hydroxybenzoic acid. Benzyldimethylamine can then be converted into ammonia by performing demethylation twice, which removes both methyl groups, followed by debenzylation, removing the benzyl group using hydrogenation.[29] The diagram represents suggested pathways of the biodegradation of BAC for both the hydrophobic and the hydrophilic regions of the surfactant. Since Stearalkonium chloride is a type of BAC, the biodegradation process should happen in the same manner.

Regulation

In September 2016, the FDA announced a ban on nineteen ingredients in consumer antibacterial soaps citing a lack of evidence for safety and effectiveness. A ban on three additional ingredients, including benzalkonium chloride, was deferred to allow ongoing studies to be completed.[30]

See also

- Stearalkonium chloride

- Polyaminopropyl biguanide, an alternative preservative for contact lens solutions

- Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid

- Triclosan

- Thiomersal

References

- 1 2 3 C&L Inventory: Quaternary ammonium compounds, benzyl-C8–18-alkyldimethyl, chlorides

- ↑ Maximilian Lackner, Josef Peter Guggenbichler "Antimicrobial Surfaces" Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2013. doi:10.1002/14356007.q03_q01

- ↑ Bartlett, J (2013). Clinical Ocular Pharmacology (2 ed.). Elsevier. p. 20. ISBN 1-483-19391-8.

- ↑ Bradosol

- ↑ Ash, M; Ash, I (2004). Handbook of Preservatives. Synapse Info Resources. p. 286. ISBN 1-890-59566-7.

- ↑ Nelson, L; Goldfrank, L (2011). Goldfrank's Toxicologic Emergencies (9 ed.). McGraw-Hill Medical. p. 803. ISBN 0-071-60593-2.

- ↑ Baudouin, C; Creuzot-Garcher, C; Hoang-Xuan, T (2001). Inflammatory Diseases of the Conjunctiva (1, illustrated ed.). Thieme. p. 141. ISBN 978-3-131-25871-7.

- ↑ Otten, Mary; Szabocsik, John M. (1976). "Measurement of Preservative Binding with SOFLENS (polymacon) Contact Lens". Clinical and Experimental Optometry. 59 (8): 277. doi:10.1111/j.1444-0938.1976.tb01445.x.

- ↑ M Akers, "Consideration in selecting antimicrobial preservative agents for parenteral product development", Pharmaceutical Technology, May, p. 36 (1984).

- ↑ Baudouin, C; Labbé, A; Liang, H; Pauly, A; Brignole-Baudouin, F (2010). "Preservatives in eyedrops: the good, the bad and the ugly". Prog Retin Eye Res. 29 (4): 312–34. PMID 20302969. doi:10.1016/j.preteyeres.2010.03.001.

- 1 2 Kennedy, D W; Bolger, W E; Zinreich, S J (2001). Diseases of the Sinuses Diagnosis and Management. B.C. Decker Inc. p. 162. ISBN 1-550-09045-3.

- ↑ Marple, B; Roland, P; Benninger, M (2004). "Safety review of benzalkonium chloride used as a preservative in intranasal solutions: an overview of conflicting data and opinions". Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 130 (1): 131–41. PMID 14726922. doi:10.1016/j.otohns.2003.07.005.

- ↑ Beule, A. G. (2010). "Physiology and pathophysiology of respiratory mucosa of the nose and the paranasal sinuses". GMS Curr Top Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 9: Doc07. PMC 3199822

. PMID 22073111. doi:10.3205/cto000071.

. PMID 22073111. doi:10.3205/cto000071. - ↑ Graf, P (2005). "Rhinitis medicamentosa: a review of causes and treatment.". Treatments in respiratory medicine. 4 (1): 21–9. PMID 15725047. doi:10.2165/00151829-200504010-00003.

- ↑ Snow, J. B.; Wackym, P. A. (2009). Ballenger's Otorhinolaryngology: Head and Neck Surgery (revised ed.). PMPH-USA. p. 277. ISBN 1-550-09337-1.

- ↑ Malo, J; Chan-Yeung, M; Bernstein, D I (2013). Asthma in the Workplace (4, illustrated, revised ed.). CRC Press. p. 198. ISBN 1-842-14591-6.

- ↑ Gerald, L B; Gerald, J K; McClure, L A; Harrington, K; Erwin, S; Bailey, W C (June 2011). "Redesigning a large school-based clinical trial in response to changes in community practice". Clin Trials. 8 (3): 311–319. PMC 3145214

. PMID 21730079. doi:10.1177/1740774511403513.

. PMID 21730079. doi:10.1177/1740774511403513. - ↑ "Safety and Effectiveness of Consumer Antiseptics; Topical Antimicrobial Drug Products for Over-the-Counter Human Use; Proposed Amendment of the Tentative Final Monograph; Reopening of Administrative Record".

- ↑ "RTECS BO3150000 Ammonium, alkyldimethylbenzyl - , chloride".

- ↑ Lewis R J Sr (2004). Sax's Dangerous Properties of Industrial Materials (11 ed.). Wiley-Interscience, Wiley & Sons, Inc. Hoboken, NJ. p. 104. doi:10.1002/0471701343.

- ↑ "TOXNET Benzalkonium Chloride Compounds".

- ↑ "Haz-Map Benzalkonium Chloride".

- ↑ "NIOSH ICSC Benzalkonium Chloride".

- ↑ Seymour Stanton Block (2001). Disinfection, sterilization, and preservation (5, illustrated ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 311. ISBN 0-683-30740-1.

- ↑ Dart, R C (2004). Medical Toxicology (illustrated, revised ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 1255. ISBN 0-781-72845-2.

- ↑ Gossel, T A (1994). Principles Of Clinical Toxicology, Third Edition (3, illustrated, revised ed.). CRC Press.

- ↑ Campbell, A; Chapman, M (2008). Handbook of Poisoning in Dogs and Cats. John Wiley & Sons. p. 17. ISBN 0-470-69844-6.

- ↑ Dyer, David; Gerenraich, Kenneth; Whams, Peter (1998). "Testing a New Alcohol-Free Hand Sanitizer to Combat Infection". AORN Journal Vol 68 Issue 2: 239–251.

- 1 2 3 4 Rowe, Raymond (2009). Handbook of Pharmaceutical Excipients 6th Edition. London, UK: Pharmaceutical Press. pp. 56–58. ISBN 978 1 58212 135 2.

- ↑ "Safety and Effectiveness of Consumer Antiseptics; Topical Antimicrobial Drug Products for Over-the-Counter Human Use". 2016-09-06. Retrieved 2016-10-05.

Further reading

- Rieger, M M (1997). "The Skin Irritation Potential of Quaternaries" (PDF). Soc. Cosmet. Chem. 48: 307–317.

- Thorup I: Evaluation of health hazards by exposure to Quaternary ammonium compounds, The Institute of Food Safety and Toxicology, Danish Veterinary and Food Administration, http://www2.mst.dk/common/Udgivramme/Frame.asp?http://www2.mst.dk/udgiv/publications/2000/87-7944-210-2/html/kap04_eng.htm%5B%5D

- Verret, DJ; Marple, BF. (Feb 2005). "Effect of topical nasal steroid sprays on nasal mucosa and ciliary function". Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 13 (1): 14–8. PMID 15654209. doi:10.1097/00020840-200502000-00005.

External links

- International Programme on Chemical Safety, International Chemical Safety Card (ICSC) - Benzalkonium Chloride

- National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), International Chemical Safety Card (ICSC) - Benzalkonium Chloride

- International Programme on Chemical Safety, Poisons Information Monograph (PIMs) - Benzalkonium Chloride

- Haz-Map Category Details - Benzalkonium Chloride

- ToxNet Human Safety Database - Benzalkonium Chloride Compounds

- Recognition and Management of Pesticide Poisonings, United States Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Pesticide Programs, Sixth Edition, 2013

- CDC Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee (HICPAC), Guideline for Disinfection and Sterilization in Healthcare Facilities, 2008

- Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. MSDS

- Spectrum Labs "Clear Bath" Algae Inhibitor MSDS

- Nile Chemicals MSDS

- TCI America MSDS

- Sciencelab.com, Inc. MSDS

- Nasal Saline Sprays - The Additives May Be the Problem