Hungarian nobility

Part of a series on the |

||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History of Hungary | ||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||

|

Medieval

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Early modern

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Late modern

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Contemporary

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

By topic |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||

The Hungarian nobility consisted of a privileged group of laymen, most of whom owned inheritable landed property, in the Kingdom of Hungary (including all the Lands of the Crown of Saint Stephen as well) between the 1260s and 1946. Late 12th-century documents used the term "noblemen" in reference to the dignitaries of the royal court and the heads of the counties. Most of these aristocrats were native lords, some even tracing their families' origins back to tribal chiefs who lived at the time of the Hungarian conquest of the Carpathian Basin around 895. Other aristocrats were regarded as newcomers, because their ancestors (mainly German, Italian and French knights) came after the establishment of the kingdom around 1000. The immigrant knights contributed to the introduction of heavy cavalry and the spread of chivalric culture. According to scholarly theories, groups of Slavic or Romanian notabilities of the polities from the period preceding the Hungarian conquest also survived.

Beside the aristocrats, less illustrious individuals held landed property and were obliged to provide military service throughout the kingdom. For instance, a privileged group of armed serfs – the "castle warriors" – held estates in the lands attached to royal castles. Through the integration of the different classes of free and non-free warriors, a new group emerged after a decline in royal power started at the end of the 13th century. They referred to themselves as "royal servants" to emphasize their direct contact to the monarch. They forced Andrew II of Hungary to spell out their liberties (including their exemption of royal taxes) in the Golden Bull of 1222, which became the fundamental document of noble privileges. The royal servants' identification as noblemen was enacted in 1267. The highest royal officials had by that time were mentioned as "barons of the realm". In short time, the counties transformed into the most important institutions of the self-government of noblemen. A decree of 1351 declared the principle of "one and the selfsame liberty" of all noblemen. However, there were groups of privileged landowners – the so-called "conditional nobles" – that did not enjoy all the privileges of "true noblemen"; for instance, they were to render military services in exchange for the estates that they held on their lords' domains. Moreover, significant economic, political and social differences existed between the wealthiest noblemen (who owned castles and dozens of villages and held sway over thousands of peasants) and noblemen who themselves cultivated their tiny plots. The rich landowners employed impoverished noblemen in their households as their familiares. Through their familiares, they could control both the counties and the Diet, or parliament.

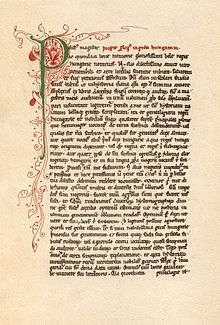

According to customary law, only sons and male members of the noble families could inherit noble estates. Noblemen's daughters were only entitled to the "daughters' quarter" which was to be given in money or movable property, except if a noble women was married off to a commoner. Only the monarch had the power to "promote a daughter to a son", authorizing her to inherit her father's estates. If a nobleman died, his estates were divided among his sons in equal parts, which contributed to the impoverishment of noble families. A group of noble families bearing hereditary titles emerged in the middle of the 15th century. First the monarchs granted the title of "perpetual count" to noblemen; the existence of "natural barons" was acknowledged from the 1480s. Nevertheless, István Werbőczy's Tripartitum – a collection of customary laws compelled in 1514 – emphasized the equal status of all noblemen and identified the Hungarian nation with the community of noblemen. The law book also summarized the noblemen's privileges, including their personal freedom and their exemption of taxation.

In some cases, not individuals but a group of people was granted a legal status similar to that of the nobility; e.g., the Hajdú people enjoyed the privileges of the nobility not as individuals but as a community.

The Latin became the language of the nobility.[1] It represented that Hungary belonged to the western states in the modern historical consciousness and served as a symbol of independence against German expansion. It also symbolised that the nobility had a common culture.[1] Latin was used at tribunals and served as lingua franca in the spheres of official life.[1]

Beginning in the 14th century, Hungarian nobility was based on a Patent of Nobility with a coat of arms issued by the monarch and constituted a legal and social class. Privileges of nobility—e.g. no taxation but obligatory military service at war at own cost—were abolished 1848, titles of nobility were abolished in 1947, and the abolishment of titles of nobility were again confirmed in 1990.

Similarly to other countries in Central Europe, the proportion of the nobility in the population of the Kingdom of Hungary was significantly higher than in the Western countries: by the 18th century, about 5% of its population qualified a member of the nobility.

The core privileges of the nobility were abolished or expanded to other citizens by the "April laws" in 1848, but the members of the upper nobility could reserve their special political rights (they were hereditary members of the Upper House of the Parliament) and the usage of names of the nobles also distinguished them from the commoners. All the distinctive features of nobility, including titles, were abolished in 1947 following the declaration of the Republic of Hungary. The abolition of titles of nobility was confirmed by parliamentary legislation in 1990.

Origins (before c. 1000)

The Magyars, or Hungarians, dwelled in the Pontic steppes in the middle of the 9th century.[2] Regino of Prüm, Leo the Wise and other contemporaneous authors portrayed the Magyars as nomadic warriors who "ride their horses all the time"[3] and "do not last long on foot".[4][5] The Magyars crossed the Carpathian Mountains in search for a new homeland after the Pechenegs invaded their lands in 894 or 895.[6] The Magyars defeated the Bavarians, annihilated Moravia, and settled in the lowlands of the Carpathian Basin.[7][8]

The Hungarians were organized into tribes and each had its own chief in the middle of the 10th century, according to Constantine Porphyrogenitus.[9][10] Porphyrogenitus also wrote that the Hungarians "do not obey their own particular princes, but have a joint agreement to fight together with all earnestness and zeal",[11] suggesting that the tribal chiefs were military commanders instead of political leaders.[10] At least the leaders of the tribes were bilingual, speaking both Hungarian and "the tongue of the Chazars",[12] according to the emperor.[13] According to historian Pál Engel, the tribal chiefs bore the title úr, as it is suggested by Hungarian terms – ország ("realm") and uralkodik ("to rule") – deriving from this word.[9] The bős, whose title derived from the Turkic bey, were military leaders subjected to the tribal chiefs.[14][15] Burials yielding sabres and other weapons, silver sabretaches, jewels and remains of horses show that a numerous class of mounted warriors existed in the first half of the 10th century.[16] They were buried either in large cemeteries where hundreds of graves of men who had been buried without weapons surrounded their burial places, or in small cemeteries with 25-30 graves.[17] There is no evidence that the chiefs lived in fortified abodes, because none of the forts in the Carpathian Basin can certainly be dated to the 10th century.[18] However, wood-and-stone houses from the same century that were unearthed in Borsod suggest that 10th-century notabilities lived in abodes made of stone and wood.[19]

The Aba, Bár-Kalán, Csák and many noble kindreds asserted a descent from 9th and 10th-century chiefs in the late 12th and early 13th centuries, but there is little evidence to substantiate their claim.[20][21] According to historian László Makkai, most of these clans bore lions on their coat-of-arms.[15] However, decorative motifs, which can be regarded as the totems of tribes (the griffin, wolf and hind) in the 10th-century, were rarely used in Hungarian heraldry in the following centuries.[20] According to historian Martyn Rady, both the Hungarians' defeats during their raids in Europe and the centralizing attempts of the grand princes from the Árpád dynasty caused the destruction of the families of the tribal chiefs.[22]

In Slovak historiography, certain noble kindreds are described as Slavic noble families which had survived the fall of Moravia.[23] For instance, Ján Lukačka writes that the Hont-Pázmány kindred, whose ancestors are mentioned as Swabian knights in medieval chronicles, was actually descended from aristocrats from the Principality of Nitra who had yielded to the Hungarian monarchs in the 10th century.[24] According to Vlad Georgescu, Ioan-Aurel Pop and other historians, Romanian landowners also survived the Hungarian Conquest in Transylvania and other regions east of the river Tisza.[25][26] Other historians (including Pál Engel and Martyn Rady) write that the presence of Romanians cannot be proven before around 1200, and their leaders, known as knezes, primarily acquired their landed propierty through settling Romanian commoners on the sparsely inhabited domains of the kings, prelates and noblemen in the 13th and 14th centuries.[27][20]

The Medieval Kingdom

The "patrimonial" kingdom (c. 1000 – c. 1193)

The first king of Hungary, Stephen I, was crowned on Christmas 1000 or 1 January 1001.[28] Stephen subjugated the tribal chiefs; he set up bishoprics and monasteries and prescribed the adoption of Christianity; he erected forts and established administrative units, known as counties, around them.[29] In the subsequent centuries, the royal family held more than two-thirds of all lands in the sparsely inhabited kingdom.[30][31] Accordingly, the "royal household was the greatest provider of largesse in the kingdom" for centuries.[32] The Palatine, the Judge royal and other court dignitaries were the most powerful men in the entire kingdom in the 11th and 12th centuries.[33] They were mentioned as maiores, optimates, proceres or magnates in contemporaneous documents.[33]

The earliest Hungarian laws show that the society was divided into two major categories.[31][34] Freemen (liber) could freely choose their lords, but the serfs (servus) were permanently bound to their masters.[31][35] Among the serfs, the castle warriors (iobagiones castri) enjoyed a privileged status: they had hereditary estates and were exempt of taxation, but were obliged to serve in the army of the head, or ispán, of the castle.[36] They jealously guarded their privileged status and litigated other serfs who attempted to seize their estates or liberties.[37] The burglaries of castle warrior and commoner estates were penalized differently by the laws of Stephen I.[38] It may imply that, beside the fact that the two groups had obviously different legal status, the houses (domus) of the castle warriors (miles) were more valuable than the commoners' abodes (mansiunculas).[38] Only the monarchs had the power to grant liberty to serfs.[39] The first such case is documented from the time of Géza II who declared one Botus, who was the son of a prelate's former serf a freeman.[39] Compensation to be paid in case of certain crimes show that freemen were divided into at least three major groups in the 11th century.[40] An ispán who abducted a girl were to give 50 steers, but a warrior, or "rich", gave 10 steers and a commoner only 5.[41] The ispáns were officials appointed and dismissed by the monarchs at will.[42][43]

Initially, the expression "nobleman" (nobilis) had no well-specified meaning: it could refer to a courtier, a landowner with judicial powers or even to a warrior.[44] In the late 12th century, only the court dignitaries and the ispáns were mentioned as noblemen.[44] Simon of Kéza, who completed his Gesta Hunnorum et Hungarorum around 1285, wrote that there were 108 noble kindreds in the kingdom.[44][21] The members of a kindred (genus or generatio) were the patrilineal descendants of a common ancestor.[45] They held their inherited domains in common through generationes,[45] but the division of the property became common in the early 13th century.[46][47] All 108 kindreds were descended from former ispáns.[21]

The members of a kindred had common patronage rights over one or two monasteries which had been established by their common ancestor.[45][46] In the early 12th century, King Coloman the Learned made a clear distinction between royal land grants made by King Saint Stephen and by later kings.[48][49] Family lands traceable back to the first king, could be inherited by the deceased owner's cousins and other relatives descending from the first grantee.[48][49] Other property could only pass from father to son, or from brother to brother, but otherwise the property escheated to the Crown.[50] From around 1156, the monarchs started granting immunities to landowners, exempting their estates of the jurisdiction of the ispáns and ceding them all royal revenues which had earlier been collected in their lands.[51]

Members of the noble kindreds distinguished themselves with a name which referred to their ancestors with the words de genere ("from the kindred") from around 1208.[46] The contemporaneous Gesta Hungarorum writes the ancestors of most noble lineages were tribal chiefs at the time of the Hungarian conquest of the Carpathian Basin, but most of them can only be traced back to the 11th and 12th centuries.[52][53] The Gesta emphasizing the hereditary right of the one-time tribal chiefs' descendants to participate in the government, stating that they "should never at all excluded from the counsel of the prince and the honor of the realm".[54][47]

Kindreds descending from foreign knights – including the Gutkeled, and Győr families – were labelled as "newcomers" (advena) for centuries.[55][56] The first foreign knights came during the reign of Stephen I's father, Géza.[56] These knights were well-equipped, mostly young, warriors who had been trained in the Western European art of war, enabling the Hungarian monarchs to set up an army of heavy cavalry.[46][57] Most knights arrived from the Holy Roman Empire, but the chronicles also refer to Aragonian, Czech, French and Italian warriors coming to the kingdom.[58][59] The monarchs granted landed estates to the newcomers "with royal liberality", as it is emphasized in a royal charter of 1156.[60] Intermarriages between families descending from newcomers and native lords were not rare, which ensured the two groups' integration.[61] For instance, Hahold, the ancestor of the Hahót kindred arrived in the 1160s, but most of his grandchildren bore Hungarian names a some decades later.[62][63]

With the arrival of foreign knights, tournaments, coat-of-arms and other elements of chivalric culture also spread.[55] Families descending from the same kindred adopted similar coat-of-arms.[55] For instance, all families of the Aba kindred had an eagle in their coat-of-arms, those of the Becse-Gergely kindred a snake.[64] From the late 12th century, noblemen often named their children after Alexander, Lancelot, Tristan and other heroes of popular chivalric romances.[55][65] The cult of Ladislaus I of Hungary, who became the Hungarian ideal of a Christian knight, also emerged in this period.[66]

Towards the first Golden Bull (c. 1193 – 1222)

Béla III was also the first monarch to give away a whole county, granting Modrus to Bartholomew of Krk.[67] In return, the king obliged him to send well-equipped warriors to the royal army.[68] Béla III also started giving away large parts of the royal demesne.[69] The new landowners wanted to subject the freemen, the castle warriors and other privileged elements who lived on or around the alienated royal estates.[70] To strengthen their personal bonds to the monarchs, they demanded royal confirmation of their status as "royal servants" (serrvientes regis).[71] A castle warrior, named Ceka, was the first to receive such a grant in the late 13th century.[72]

Béla III's younger son, Andrew II, who mounted the throne in 1205, decided to "alter the conditions" of his realm and to "distribute castles, counties, lands and other revenues" to his officials, as he narrated in a charter of 1217.[73] He gave up granting the estates as a fiefs, with an obligation to render services in the future, but as an allods, in reward for the grantee's previous acts.[74] Donations to such a large scale accelerated the development of a wealthy group of landowners, most descending from noble kindreds, who monopolized the nearly 25 highest offices.[75][76] The Palatine, the Judge royal, the Voivode of Transylvania, the Ban of Croatia, the Master of the horse, the Master of the cupbearers and other court dignitaries were mentioned as "barons of the realm" (barones regni) instead of noblemen from around the same period.[75]

Age of Golden Bulls (1222 – 1267)

The barons' emerging power endangered the royal servants who lived far from the royal court, subjected to their wealthy neighbors' tyrannical acts.[77] Their movement compelled Andrew II to issue to confirm their liberties in a royal charter known as Golden Bull in 1222.[78][79][80] This "East European document most resembling the Magna Carta"[81] declared that all royal servants were exempt from royal taxes.[80][82] The Bull also stated that they were only to fight in the royal army in case of an invasion against the realm.[83] It confirmed the royal servants' right to freely will their (inherited or granted) estates in absence of male heirs, with the exception of one-quarter of their possessions (the "daughters' quarter", or quarta filialis) which was their daughters' due.[80] Royal servants were also exempted of the jurisdiction of others than the monarch and the Palatine and their arrest without a verdict was prohibited.[84][85] The Golden Bull authorized the prelates and the magnates to resist the monarch who failed to respect its provisions.[81]

The Golden Bull and its first renewal in 1231 also prescribed that castle warriors "shall be preserved in the liberties established"[86] by King St Stephen.[87] However, castle warriors and other armed landowners living in the prelates' domains remained subjected to the jurisdiction of their lords.[88] Accordingly, the royal servants' liberties distinguished them from all other subjects of the kings of Hungary.[88] They called themselves as noblemen from the 1220s,[89] and developed the institutions of their self-government at the level of the counties.[90][91] The first document attesting this process is a charter of Andrew II from 1232.[90] The king authorized the royal servants of Zala County "to judge and do justice" in the county which had been in a state of anarchy.[92] In the same year, Bartholomew le Gros, Bishop of Pécs, took a legal action against Atyusz, Ban of Slavonia, before the royal servants' community of this county, showing that he was willing to accept their jurisdiction.[92] In the following years, the royal servants elected magistrates who were called "judges of the nobles" from among their numbers in more and more counties.[92]

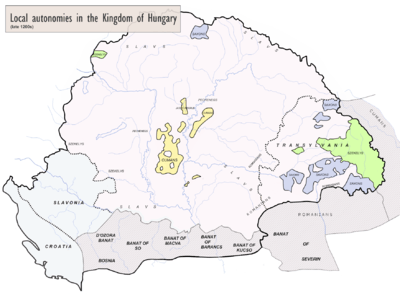

The Mongol invasion brought destruction in Hungary in 1241 and 1242.[93] The invasion proved the importance of well-fortified places and heavy cavalry.[94][95] Béla IV authorized many prelates and lay lords to build fortresses on their domains, although the erection of fortresses had so far been a royal prerogative.[96] More than 50 new castles were built between 1242 and 1270; only about 20 of them were erected on royal domains.[97] Because castles could not be kept without proper income, villages were attached them on a permanent basis.[98] To muster military forces for the protection of the new royal castles in Upper Hungary (in present-day Slovakia), Béla IV granted estates to warriors and liberated local serfs, obliging them to equip a specified number of armoured knights or to provide services for the keeper of the castle.[99] In contrast with the royal servants, these groups of landowners – including the "sons of servants" (filii iobagionum) of Zólyom County and the "ten-lanced nobles" in Szepes – held their estates conditionally, in exchange for services to be rendered.[100] A royal charter of 1247 shows that the Romanian knezes, or chiefs, were likewise obliged to provide services to the heads of the Banate of Severin.[101] In contrast with true noblemen, these groups of privileged landowners, or "conditional nobles", were to serve their lords in exchange the estates they held on their lords' domainst, but their services were rarely defined in details.[102] Royal charters referred to royal servants as noblemen from the 1250s.[103] Béla IV, who had for decades failed to meet their representatives, attended an assembly "of the nobles of all Hungary who are called royal servants" in Esztergom in 1267.[104][105] The assembly passed a decree that confirmed the noblemen's privileges, mostly in accordance with the Golden Bull of 1222, but in some cases, the new wording differed from the original text.[104]

The partition of the landed property among the male heirs to the deceased owner, which became customary in the 13th century, led to the reduction in size of noble estates.[106] Most noblemen only owned a single village and many of them could not even arm themselves.[107] Occasionally, noblemen sold their estates and lost their noble status.[108] For instance, in 1268, the sons of a castle warrior named Chaz went to court to restore their family estates at Hódosd (now Hodoş in Romania) that had been lost because of their grandfather's "cupidity".[109]

Noble counties and oligarchs (1267 – 1321)

The judges of the nobles, who knew local customs, took charge of exercising justice in the counties.[92] New local courts of justice – known as sedes iudiciaria or sedria – came into being; the ispán or his deputy presided these courts, but they were consisted of four (in Transylvania and Slavonia, of two) judges of the nobles.[92][104] A decree of 1290 prohibited the Palatine and the ispáns "to accept a judgement or judge without four elected nobles".[110][111][112] The "general assemblies" (congregatio generalis) of the counties also developed into important institutions.[113] Initially, they were primarily forums for detecting and proscribing criminals.[114] The establishment of the sedria and the general assembly marked the transformation of the counties from an institution of royal authority into "noble counties",[104] institutions of the local noblemen's autonomy.[115]

Noblemen became also involved in legislation through the development of the Diet of Hungary, which was a medieval form of the parliament.[104][116] At the first Diet, which was held in 1277, the barons of the realm and the representatives of the noblemen and the Cumans were present.[116] A decree of 1290 prescribed that the noblemen's representatives should have seats in the royal council, but this decree was seldom respected.[104] The contemporaneous Simon of Kéza emphasized, in his Gesta Hungarorum, that the community of the noblemen had a preeminent role in the government of the country.[116] He identified the "pure Hungarian nation"[117] with the noble clans which were descended from tribal chiefs.[118]

The erection of private castles drastically changed the relationship between the kings and their barons.[119] Up to that time, a baron had seldom been able to openly oppose the monarch.[120] However, a baron who owned a well-fortified castle could take refuge in the castle in case of a conflict.[120] Furthermore, "castle bred castle" (Erik Fügedi)[121] because attempts by the lords of the newly built castles to expand their domains forced the neighboring landowners to erect new fortresses.[122] For instance, shortly after the Geregye clan had two castles erected at Adorján and Sólyomkő (present-day Adrian and Şoimeni in Romania) in Bihar County, three new fortresses were built in the same county: a castle at Fenes (now Finiș) for the Bishop of Várad, a fortress at Kőrösszeg (now Cheresig) for the Borsa family, and a tower at Diószeg (present-day Diosig) for members of the Gutkeled kindred.[123] About 170 new fortresses were built in the kingdom between 1271 and 1320, and less than 15% of them for the monarchs.[124] Most castles consisted of a tower which was surrounded by a fortified courtyard, but in many cases, for instance at Szigliget, the tower was part of the walls of the castle.[125]

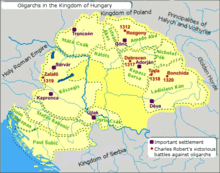

A long period of anarchy followed the reign of Béla IV's son, Stephen V, who died in 1272.[126] Powerful landowners took control of large contiguous territories, transforming them into their own provinces where royal authority was only nominal.[127] The monarchs could not appoint and dismiss their barons and ispáns at will any more.[127] The most powerful noblemen, who are known as "oligarchs" in modern historiography, appropriated royal prerogatives, combining private lordship "with an official power and with the judicial authority that went with it" (Pál Engel).[128] When Andrew III, the last male member of the Árpád dynasty, died in 1301, about a dozen lords – including Amade Aba, Matthew Csák, Ladislaus Kán, and Paul Šubić – held sway over most parts of the kingdom.[129]

It was customary from the end of the 13th century for noblemen to enter the service of wealthier landowners and become a member of their household, or "familia".[130][131] A familiaris was required to provide services to his lord in exchange for a fixed salary or a portion of revenue, or rarely for the ownership or usufruct of a piece of land.[131] If the king nominated a noblemen ispán, or elevated him to a higher office, the newly appointed official customarily appointed his familiares to offices subordinated to him.[131] Nevertheless, the familiares remained independent landholders and reserved their liberties, including their direct contact to the sovereign.[132][133]

The Angevins' monarchy (1321 – 1382)

Stephen V's great-grandson, Charles I, a scion of the Capetian House of Anjou, restored royal power in the first decades of the 14th century.[134][135] He seized almost half of the castles in Hungary, which again ensured the preponderance of the royal demesne.[134][136] He did not hold Diets after 1320, emphasizing his claim to rule with "the plenitude of power".[137] He refused to confirm the Golden Bull in 1318,[138] but he exempted the Transylvanian noblemen from all taxes payable to the Voivodes.[139]

Charles I based royal administration on a system of "honors", or "office fiefs",[136] nominating his partisans to high offices and allowing them to retain all income from these offices, including revenues from the royal castles that Charles I allocated to them for the period of their office-holding.[134][140] About 20 court dignitaries obtained the honorific "magnificus vir" in Charles I's reign, which distinguished them from the masses of noblemen.[141] However, their offices were not hereditary, even if in some cases members of the same family succeeded each other in the same office.[142] For instance, three members of the Drugeth family held the office of Palatine between 1323 and 1342.[143] A wealthy office-holders was expected to muster an army among their familiares, which was named as banderium after the Italian word for banner (bandiera).[144]

Charles was willing to ignore local customs.[137][145] For instance, he granted the right to daughters of noblemen who had no sons to inherit their father's estates.[146] This practise of "promotion of a daughter to a son" (praefectio in filium), which was first recorded in 1332, was harmful to the interests of the grantees' cousins and other male relatives.[147][148] According to customary law, only sons were regarded as heirs to their fathers' estates, the daughters' quarter were to be given in cash or movable goods.[149] A verdict of 1346 declared that a noble woman who was given in marriage to a commoner should receive her quarter "in the form of an estate in order to preserve the nobility of the descendants born of the ignoble marriage".[150] In practise, her husband was also regarded as a nobleman – a "noble by his wife" (post uxorem nobile) – in Nyitra, Sáros, Zala and other counties.[151]

Charles's son and successor, Louis I, convoked a Diet in late 1351 after his invasions of the Kingdom of Naples between 1347 and 1350 and the destruction brought by the Black Death in 1349.[152][153] Stating the all true noblemen enjoy "one and the selfsame liberty" (una eademque libertas) in his realms, the king renewed the Golden Bull, with the exception of the provision entitling noblemen who had no sons to bequeath their estates.[154][152][155] Instead, the king introduced the entail system (aviticitas), prohibiting noblemen to freely dispose of their property and prescribing that the estates of childless noblemen "should descend to their brothers, cousins and kinsmen".[155] The decree exempted all noblemen from paying extraordinary taxes, but stipulated that their households are subject to the so-called "chamber's profit" (lucrum camarae), a tax introduced in 1323.[82] At the same Diet Louis I ordered that the "ninth" – a tax assessed on agricultural products which was payable to the landowner – were to be collected from the peasants in all noblemen's estates, which hindered landowners from competing for manpower through offering lower taxes or tax holidays for peasants who moved to their lands.[155]

Noblemen and landowners were often identified in royal charters from the second half of the 14th century.[156] A nobleman lived in his own house which stood on his own land, "in the way of noble" (more nobilium), in contrast with a commoner who did had land and lived "in the way of peasants" (more rusticorum).[157] Regional differences also disappeared.[157] The decree of 1351 emphasized that the noblemen in Slavonia and Transylvania enjoyed the same liberties as their peers in Hungary proper.[157] The so-called sons of servants in Upper Hungary were either received a charter of nobility from the sovereign or were tacitly integrated in community of the true noblemen of the counties.[158] The kings ennobled many Romanian knezes in Máramaros (now Maramureș in Romania and Maramorosh in Ukraine) between 1326 and 1360 and their descendants developed the region into a self-governing county in 1380.[159] The status of conditional noblemen – for instance, the "nobles of the Church" (praediales), ten-lanced nobles of Szepes and Romanian knezes – remained distinct from the true noblemen.[160] They developed their own institutions of self-government, which were known as "seats" (sedes) or "districts" (districtus) instead of county.[161]

Attempts to convert Orthodox landowners to Catholicism were recorded during the reign of Louis I.[162] For instance, in 1366 he ordered that only Catholic noblemen and knezes were allowed to hold estates in the Romanian district at Karánsebes (now Caransebeș in Romania) in 1366.[163] However, in other parts of the kingdom, Orthodox landowners lived undisturbed.[159]

Louis I preferred the sons of his father's barons when nominating his officials, which contributed to the development of an "inner circle" of noblemen.[164] They were styled magnificus even when they did not hold any higher office.[164] The heads of the counties lost their right to use a distinctive banner and an authenticating seal, with the exception of the ispán of Pozsony County, who thus preserved a position equal to the barons of the realm.[165] Both Charles I and Louis I often gave immunities to landowners, exempting their estates and the peasants living there of the jurisdiction of the sedria.[166] Many landowners also received ius gladii (the right to punish (execute or mutilate) criminals who were captured in their estates).[167]

The emerging Estates (1382 – 1453)

Royal power declined after Louis I's death in 1382.[168] Sigismund of Luxembourg, who had married Louis I's daughter and successor, Queen Mary, in 1385, was elected king after he joined a league formed by a group of wealthy barons in early 1387.[169] He promised that he would only nominate his allies and their offspring to high offices.[170] In the next decade, Sigismund gave away more than 50% of the royal castles and about 67% of the villages of the royal demesne to his supporters.[171][172] Sigismund founded a new chivalric order, the Order of the Dragon, in 1408 to award his supporters.[173]

The expansion of the Ottoman Empire reached the southern frontiers in the 1390s.[174] The Crusade of Nicopolis of 1396 ended with the annihilation of the crusaders' army.[175] In order to strengthen the defense, Sigismund held a Diet in Temesvár (now Timișoara in Romania) in 1397.[176] Most provisions of the Golden Bull were confirmed, but a decree prescribed that all noblemen were obliged to join a defensive campaign against the Ottoman Empire.[176] The Diet also ordered the establishment of a militia, obliging all landowners to equip a light horseman after for 20 peasant plots on their domains.[177] Noblemen who individually owned lesser plots were to join together.[178]

The decrees of the Diet of Temesvár referred to the members of the wealthiest noble families as "barons' sons" (filii baronum), distinguishing them from the masses of the nobles.[179] About 40 families belonged to this group at the end of Sigismund's rule.[180] The size of their domains was 600 to 3,000 km2 (150,000 to 740,000 acres) where thousands of peasant families lived and worked for them.[180] Rulers of neighboring states also received large domains from Sigismund.[181] He donated Fogaras (now Făgăraș in Romania) to Mircea the Great, Prince of Wallachia in 1395, and about 15 domains to Stefan Lazarević, Despot of Serbia, in 1411 and during same period entire Váh river with 15 castles to duke Stibor of Stiboricz.[181] The first stable aristocratic residences – new or renovated comfortable castles – were built during the reign of Sigismund.[182] For instance, new castles were built for the Kanizsais at Kismarton (now Eisenstadt in Austria), the Újlakis in Várpalota, and for Filippo Scolari at Ozora.[182]

The aristocrats were followed by about 200-300 noble families, most of them descending from 13th-century noble kindreds, who owned more than 200 peasant plots and lived in their own households.[179] Most familiares of the magnates were "petty noblemen"[183] who had 20-200 peasant plots.[184] However, less than one-third of the nobility belonged to this group. Most noblemen owned less than 20 peasant plots, including those who cultivated their own single plots and were known as "curialists" (nobiles sessionales).[185] In the middle of the 15th century, these poor noblemen made up about 1-3% of the total population.[184] The judges of the nobles were customarily elected from among their number, they were also employed as lower county officials, mercenaries or lawyers.[184]

After the long reign of Sigismund, who died in 1437, the noblemen's attempts to increase their influence transformed the system of government.[186] Sigismund's son-in-law and successor, Albert of Habsburg, was elected king only after he promised that he would appoint his Palatine with the consent of the Diet and would only exceptionally proclaim the noblemen's general levy.[187][188] After his death, a civil war broke out between the partisans of his infant son, Ladislaus the Posthumous, and the supporters of Vladislaus III of Poland.[189] Ladislaus the Posthumous was crowned with the Holy Crown of Hungary in full accordance with the ancient customs, but the majority of the noblemen supported his opponent.[190] The Diet proclaimed the coronation invalid, emphasizing that "the crowning of kings is always dependent on the will of the kingdom's inhabitants, in whose consent both the effectiveness and the force of the crown reside".[190] With this decision, the Diet took a decisive step towards the formation of a "corporate state", featured by the dominant position of the Estates of the realm in the government.[190][191]

Thereafter the Diet, which was convoked in almost each year, transformed from a consultative body into an important institution of law-making.[192] Along with the prelates and the barons of the realm, the most prominent noblemen attended the Diet in person.[192] Other noblemen were represented by delegates who were elected at the general assemblies of the counties in Hungary proper and by the general assemblies of the realm in Croatia, Slavonia and Transylvania.[192] Occasionally, for instance, in 1446 when John Hunyadi was elected regent, all noblemen were personally convoked to the Diet.[192][193] Nevertheless, Diets were dominated by the wealthiest noblemen, because the representatives of most counties where their familiares.[194][193] A decree of 1447 declared that all noblemen was exempted of the chamber's profit and the ecclesiastic tithes.[82] On the other hand, curialists often had to pay at least the half amount of the taxa portalis, a tax otherwise assessed on peasants' households.[195]

The birth of titled nobility and the Tripartitum (1453 – 1526)

A noble father could not disinherit his sons.[196] The so-called "betrayal of fraternal blood" (proditio fraterni sanguinis) – a kinsman's "deceitful, sly, and fraudulent deprivation or disiheritance"[197] of his rights – was a crime, according to customary law.[198] The division of a nobleman's estate among his heirs impoverished many noble families.[199] For instance, Stephen Bánffy of Losonc held 68 villages at his death in 1459, but the same villages were divided among his 14 descendants in 1526.[200] To avoid this, many noblemen remained unmarried, which could cause the dying out of their families.[200] For instance, from among the 36 wealthiest families of the late 1430s, only 25 existed in 1490, and only 8 families survived the next 80 years.[200]

John Hunyadi was the first to receive a hereditary title.[201] Ladislaus the Posthumous, whom the Diet had acknowledged as lawful king, rewarded him with the Saxon district of Beszterce (now Bistrița in Romania) and the title "perpetual count" (perpetuus comes) in 1453.[202][201] During the reign of John Hunyadi's son, Matthias Corvinus, who was elected king in early 1458, further noblemen received the hereditary title of perpetual count.[203][204] Historian Erik Fügedi writes that 1487 is the "birthdate of the estate of magnates in Hungary", because the existence of a hereditary group of barons was officially acknowledged in an armistice between Hungary and the Holy Roman Empire in this year.[203] In this document, Matthias listed 23 noble families as "natural barons" (barones naturales), contrasting them with the Palatine, the Judge royal and other high officials, who were mentioned as "barons because of their position" (barones ex officio).[203]

The Diet regained its pre-eminent position, which had been lost in the last years of Matthias's reign, under his successor, Vladislaus II, who was crowned king in 1490.[205] The Diets passed hundreds of decrees in an attempt to increase the influence of the lesser noblemen.[205] For instance, a decree of 1498 prescribed that 8 noblemen should be elected to join the royal council.[206] The Diet of 1498 ordered the compilation of customary law.[207] A nobleman of Ugocsa County (now in Ukraine), István Werbőczy, completed the task in 1514.[208] Werbőczy's law-book – The Custormary Law of the Renowned Kingdom of Hungary in Three Parts, or Tripartitum – was never enacted, because the king refused to sanction it.[209] Even so, it was regularly cited and consulted at the local courts of justies in the subsequent centuries.[209][210][211] Werbőczy's work identified the Hungarian nation with the community of noblemen, stating that all noblemen "are members of the Holy Crown",[212] the symbol of the realm.[213] He anachronistically emphasized the principle of "one and the selfsame liberty", although he admitted that a baron's weregild and his widow's dower was higher than in the case of a nobleman.[214] The ninth chapter of the first part of the Tripartitum – the so-called Primae Nonus – summarized the basic liberties of all noblemen in four points.[213] According to these points, noblemen were only subject to the monarch's authority and could only be arrested in a due legal process, furthermore, they were exempted of all taxes and were entitled to resist the king if he attempted to interfere with their privileges.[215]

The Diets passed decrees which limited the peasants' rights or increased their burdens after 1490.[216] For instance, the peasants' traditional right to free movement was restricted and their labour dues were increased.[216][217] Grievances of the peasantry culminated in a rebellion of elementary force in 1514, which was led by György Dózsa.[218] The rebels pillaged manors, raped noble women and murdered noblemen, especially in the Great Hungarian Plain.[219] John Zápolya, Voivode of Transylvania, annihilated their main force at Temesvár on 15 July, which put an end to the rebellion.[220] In retaliation, the Diet deprived the peasants of the right to free movement, condemning them to "perpetual servitude".[221]

Early modern and modern times

Ottoman domination and fights for the Estates' privileges (1526 – 1711)

The Ottomans annihilated the royal army in the Battle of Mohács on 29 August 1526.[222] King Louis II died while fleeing from the battlefield.[222] Within two months, two claimants – John Zápolya and Ferdinand I of Habsburg – were elected kings and a civil war broke out.[223] John Zápolya who had accepted the suzerainty of the Ottoman Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent died in July 1540.[224][225] His partisans elected his infant son, John Sigismund Zápolya, king.[225] Ferdinand I attempted to unite the kingdom, but Sultan Suleiman intervened and seized Buda in August 1541.[225] The Sultan acknowledged John Sigismund's rule in the territories east of the river Tisza, including Transylvania.[226] The Sultan's decision completed the division of the medieval Kingdom of Hungary into three parts.[226] The northern and westernmost territories, known as Royal Hungary, remained under the rule of the Habsburgs.[227][228] The eastern regions developed into the autonomous Principality of Transylvania.[229] The central territories, known as Ottoman Hungary, were transformed into Ottoman provinces.[230] From the latter territories, most noblemen fled to Royal Hungary or to the Principality of Transylvania.[231] Peasants living in the border regions were forced to continue to pay taxes to their former lords.[232]

In the emerging Principality of Transylvania, the noblemen formed one of the three Estates of the realm.[233] Their influence on government was limited, because the princes of Transylvania were the largest landowners in their realm.[233] On the other hand, the princes were willing to help the Estates in Royal Hungary to protect their privileges against the monarchs.[234] Three peace treaties – the Peace of Vienna of 1606, the Peace of Nikolsburg of 1621, and the Peace of Linz of 1645 – concluded between the Habsburgs and the princes referred to the noblemen's liberties in Royal Hungary.[235]

The Habsburg monarchs of Royal Hungary did not maintain an independent royal court in Hungary or a separate division for Hungary in their unified court in Vienna.[236] However, they continued to appoint the Hungarian court dignitaries who had a seat in the royal council.[236] The functions that the royal court used to play in the social and cultural life were partially taken over by the wealthiest noblemen's manors.[237] These manors also became important centers of the spread of Reformation.[238] Tamás Nádasdy, Peter Perényi, and George Báthori were among the eminent supporters of reformist preachers.[239] Lutheranism became the predominant religion among noblemen living in the western regions of Royal Hungary; those who lived in the eastern regions and in Transylvania mostly adhered to Calvinism.[239] In Transylvania, even anti-Trinitarian ideas spread, but most Unitarian noblemen fell in a battle in the early 1600s.[240]

Dozens of palaces were fortified with walls made of earth and timber in the border regions in the 1540s and 1550s.[232] The wealthiest landowners hired mercenaries and settled armed runaway noblemen and serfs on their estates in the border regions.[241][242] These soldiers developed into a separate social group who attempted to receive a privileged status.[243] The "largest collective ennoblement" was performed by Stephen Bocskai, Prince of Transylvania, who donated 7 settlements in the Partium to the community of 10,000 soldiers, known as Haiduks, in 1605, exempting them of taxation and granting them the right to self-government.[244] Although noblemen continued to be identified as landowners, the number of "armalists" – noblemen who received a charter of ennoblement but did not hold a single plot of land – increased.[183] Armalists and curialists, who were unable to perform military obligations, did not enjoy all liberties.[183] Being obliged to pay taxes, they became known as "taxed noblemen" in the 16th century.[183]

In Vienna, noblemen from the Habsburgs' various realms were competing against each other for court offices.[245] The development of a "supranational aristocracy" – noble families from different realms who were related to each other through marriages – began in the second half of the 16th century.[246] For instance, the Thurzó and Zrinyi families had close family links with the Czech Kolovrat and Lobkowicz, and the Tyrolian von Arco families.[247] Noble families from the Habsburgs' other realms often received Hungarian citizenship.[246] For instance, the Diet of Pressburg of 1563 granted citizenship to three members of the Salm family and Scypius von Arco.[248] The number of titled noble families significantly increased from the 1540s.[249] About 35 families received the title baron before 1600, and further 80 families in the first half of the 17th century.[249][250] In most cases, the title was granted in connection with the grantees' military career.[251] The division of the Diet into two chambers was enacted in 1608.[252][228] The Upper House consisted of the Catholic prelates, the court dignitaries and the members of the titled noble families, including the members of the foreign aristocratic families that had received Hungarian citizenship.[252] The Lower House primarily consisted of the delegates of the counties, the free royal towns and the cathedral chapters, but the widows of titled noblemen also had a seat in this chamber.[253]

Cooperation and absolutism (1711 – 1848)

The old concept of Natio Hungarica came to play a role in the development of early nationalism based on the French model.[254] Ľudovít Štúr indirectly demanded that all people (including peasants) living in the Kingdom of Hungary have their own representatives in the Diet. He indicated thenew constitutional subject that is all the peoples in the Kingdom of Hungary should become the Natio Hungarica. This involved the amendment of the meaning of the traditional class concept Natio Hungarica and the extension of its frame to all the peoples in the Hungarian Kingdom. His attempt at the transformation of all the peoples in kingdom into Natio Hungarica constituted an attempt at the transformation of all ethnic groups in Hungarian Kingdom into Natio Hungarica. Only with the abolition of nobility and the development of Hungarian nationalism did natio Hungarica begin to develop an ethnic sense. Lajos Kossuth identified the historical-political rights of king and corporations in the Kingdom of Hungary with the national rights of the Magyars.[255]

Revolutions and counter-revolution (1918 – 1920)

After the resignation of the Berinkey government, the Communist leader Béla Kun took over the power from Mihály Károlyi's administration. He ordered the abolition of all titles and ranks of the Hungarian nobility and nationalized the aristocratic estates.[256]

Abolition of nobility (1945 – 1947)

The Statute IV of 1947 regarding the abolition of certain titles and ranks,[257] a law still in force in the Republic of Hungary, declares the abolition of hereditary noble ranks and related styles and titles, also putting a ban on their use.

Unofficial nobility (after 1947)

After 1989

The Statute survived the political change after the fall of the single-party system and the ongoing deregulation processes during and after the 1990s (see for example Statute LXXXII of 2007,[258]) and it is still in force today. Multiple attempts have been made to have the Statute revoked, none of them succeeded.

In 2009 the Constitutional Court rejected a motion requesting the revocation of 3. § (1) - (4), the ban of using certain titles. Commenting on the rejection, the Constitutional Court felt it

| “ | ... necessary to add that the Statute serves the abolition of discrimination of people on the basis of descent, which is, as the ministerial rationale of the bill conveys, "can not be compatible with the democratic public and social arrangement standing on the basis of equality. Thus, the Statute is supported by such a definite system of values that is consonant with, moreover, is an integral part of the values derived from paragraph 70/A. § (1) of the Constitution in force, prohibiting discrimination. | ” |

On September 27, 2010 (nearing the finish of the campaign for the municipal elections) István Tarlós (at the time running for the seat of Mayor in Budapest, nominated by the governing party Fidesz) and Zsolt Semjén (Deputy Prime Minister of Hungary, Christian Democratic People's Party, also member of the government), among many other politicians, have been initiated into the Vitéz Order,[259] an act the Statute explicitly prohibits.

In December 2010 two members of the opposition party JOBBIK presented a motion to revoke parts of the Statute.[260] This motion has later been revoked.[261]

In March 2011, during the drafting process of a new constitution, the possibility of revoking all legislation between 1944 and 1990 was raised.[262]

List of titled noble families

References

- 1 2 3 Nagy, Péter Tibor (2006). "The rise of conservatism and ideology in control of Hungarian education 1918-1945". The social and political history of Hungarian education. Education and Society PhD School - University of Pécs - John Wesley College - Budapest. Retrieved 4 November 2014.

- ↑ Berend, Urbańczyk & Wiszewski 2013, pp. 71, 73.

- ↑ The Chronicle of Regino of Prüm (year 889), p. 206.

- ↑ The Taktika of Leo VI (18.61), p. 459.

- ↑ Engel 2001, pp. 15–16.

- ↑ Berend, Urbańczyk & Wiszewski 2013, pp. 76–77.

- ↑ Engel 2001, pp. 12–13.

- ↑ Rady 2000, p. 11.

- 1 2 Engel 2001, p. 20.

- 1 2 Berend, Urbańczyk & Wiszewski 2013, p. 105.

- ↑ Constantine Porphyrogenitus: De Administrando Imperio (ch. 40), p. 179.

- ↑ Constantine Porphyrogenitus: De Administrando Imperio (ch. 39), p. 175.

- ↑ Bak 1993, p. 273.

- ↑ Kontler 1999, p. 44.

- 1 2 Makkai 1994, p. 11.

- ↑ Engel 2001, p. 18.

- ↑ Engel 2001, p. 17.

- ↑ Berend, Urbańczyk & Wiszewski 2013, p. 107.

- ↑ Wolf 2008, pp. 13-14.

- 1 2 3 Rady 2000, p. 12.

- 1 2 3 Engel 2001, p. 85.

- ↑ Rady 2000, p. 13.

- ↑ Lukačka 2011, pp. 31, 33–36.

- ↑ Lukačka 2011, p. 32–34.

- ↑ Georgescu 1991, p. 40.

- ↑ Pop 2013, p. 40.

- ↑ Engel 2001, pp. 119, 270-271.

- ↑ Cartledge 2011, p. 11.

- ↑ Berend, Urbańczyk & Wiszewski 2013, pp. 148–149, 152–155, 158.

- ↑ Engel 2001, p. 80.

- 1 2 3 Rady 2000, p. 16.

- ↑ Rady 2000, p. 17.

- 1 2 Berend, Urbańczyk & Wiszewski 2013, p. 193.

- ↑ Engel 2001, p. 66.

- ↑ Engel 2001, pp. 66–67.

- ↑ Engel 2001, pp. 71–72.

- ↑ Rady 2000, p. 20.

- 1 2 Balassa 1997, p. 292.

- 1 2 Kristó 1998, p. 193.

- ↑ Engel 2001, p. 69.

- ↑ Engel 2001, pp. 69–70.

- ↑ Engel 2001, p. 73.

- ↑ Fügedi 1986b, pp. 54–55.

- 1 2 3 Rady 2000, p. 28.

- 1 2 3 Fügedi 1986b, p. 25.

- 1 2 3 4 Rady 2000, p. 29.

- 1 2 Engel 2001, p. 87.

- 1 2 Rady 2000, p. 25.

- 1 2 Fügedi 1986b, p. 44.

- ↑ Rady 2000, p. 26.

- ↑ Rady 2000, p. 25, 189.

- ↑ Rady 2000, p. 23.

- ↑ Berend, Urbańczyk & Wiszewski 2013, p. 275.

- ↑ Anonymus, Notary of King Béla: The Deeds of the Hungarians (ch. 6.), p. 19.

- 1 2 3 4 Engel 2001, p. 86.

- 1 2 Fügedi 1986b, p. 13.

- ↑ Fügedi & Bak 2012, p. 324.

- ↑ Fügedi & Bak 2012, p. 323.

- ↑ Fügedi 1986b, pp. 13–14.

- ↑ Fügedi 1986b, pp. 14–17.

- ↑ Fügedi & Bak 2012, p. 326.

- ↑ Fügedi & Bak 2012, p. 321.

- ↑ Bak 1993, p. 275.

- ↑ Engel 2001, pp. 86–87.

- ↑ Fügedi & Bak 2012, pp. 327–328.

- ↑ Rady 2000, p. 129.

- ↑ Berend, Urbańczyk & Wiszewski 2013, pp. 275, 286.

- ↑ Berend, Urbańczyk & Wiszewski 2013, p. 286.

- ↑ Makkai 1994, p. 23.

- ↑ Rady 2000, p. 35.

- ↑ Rady 2000, p. 36.

- ↑ Fügedi 1998, p. 35.

- ↑ Cartledge 2011, p. 20.

- ↑ Engel 2001, p. 93.

- 1 2 Engel 2001, p. 92.

- ↑ Berend, Urbańczyk & Wiszewski 2013, pp. 426–427.

- ↑ Fügedi 1986b, p. 36.

- ↑ Berend, Urbańczyk & Wiszewski 2013, pp. 428–429.

- ↑ Makkai 1994, pp. 24–25.

- 1 2 3 Cartledge 2011, p. 21.

- 1 2 Makkai 1994, p. 25.

- 1 2 3 Rady 2000, p. 146.

- ↑ Berend, Urbańczyk & Wiszewski 2013, p. 429.

- ↑ Engel 2001, p. 95.

- ↑ Rady 2000, pp. 40, 103.

- ↑ The Laws of the Medieval Kingdom of Hungary, 1000–1301 (1222:19), p. 34.

- ↑ Kristó 1998, pp. 213, 219.

- 1 2 Engel 2001, p. 94.

- ↑ Rady 2000, p. 43.

- 1 2 Berend, Urbańczyk & Wiszewski 2013, p. 431.

- ↑ Fügedi 1986b, p. 63.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Rady 2000, p. 41.

- ↑ Berend, Urbańczyk & Wiszewski 2013, p. 445.

- ↑ Kontler 1999, p. 78–80.

- ↑ Engel 2001, pp. 103–105.

- ↑ Engel 2001, p. 104.

- ↑ Fügedi 1986a, pp. 53-54.

- ↑ Fügedi 1986a, pp. 73-74.

- ↑ Rady 2000, pp. 86-87.

- ↑ Rady 2000, pp. 79, 86.

- ↑ Rady 2000, p. 91.

- ↑ Rady 2000, pp. 79, 83, 88, 93–94.

- ↑ Rady 2000, pp. 38, 40.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Engel 2001, p. 120.

- ↑ Rady 2000, p. 40.

- ↑ Rady 2000, pp. 45-46.

- ↑ Rady 2000, p. 46.

- ↑ Rady 2000, p. 47.

- ↑ Rady 2000, p. 48.

- ↑ The Laws of the Medieval Kingdom of Hungary, 1000–1301 (1290:3), p. 42.

- ↑ Rady 2000, pp. 41, 190.

- ↑ Fügedi 1986b, p. 64.

- ↑ Rady 2000, p. 42.

- ↑ Fügedi 1986b, pp. 64-67.

- ↑ Berend, Urbańczyk & Wiszewski 2013, pp. 431-432.

- 1 2 3 Berend, Urbańczyk & Wiszewski 2013, p. 432.

- ↑ Simon of Kéza: The Deeds of the Hungarians (ch. 2.6), p. 23.

- ↑ Engel 2001, p. 122.

- ↑ Fügedi 1986a, p. 128.

- 1 2 Fügedi 1986b, p. 95.

- ↑ Fügedi 1986b, p. 73.

- ↑ Fügedi 1986b, pp. 72-73.

- ↑ Fügedi 1986b, p. 65.

- ↑ Fügedi 1986b, p. 54.

- ↑ Fügedi 1986a, p. 82.

- ↑ Berend, Urbańczyk & Wiszewski 2013, p. 430-431.

- 1 2 Engel 2001, p. 124.

- ↑ Engel 2001, p. 125.

- ↑ Engel 2001, pp. 126-127.

- ↑ Engel 2001, p. 126.

- 1 2 3 Rady 2000, p. 110.

- ↑ Kontler 1999, p. 76.

- ↑ Engel, Kristó & Kubinyi 1998, p. 133.

- 1 2 3 Cartledge 2011, p. 34.

- ↑ Engel 2001, pp. 128, 130-134, 382-383.

- 1 2 Kontler 1999, p. 89.

- 1 2 Engel 2001, pp. 140-141.

- ↑ Engel 2001, p. 141.

- ↑ Makkai, László (2001). "Transylvania in the medieval Hungarian kingdom (896–1526): From the Mongol invasion to the Battle of Mohács: Barons and other nobles". History of Transylvania, Volume I.: From the Beginnings to 1606. Columbia University Press. Retrieved 27 October 2014.

- ↑ Engel 2001, p. 121.

- ↑ Fügedi 1986b, p. 188.

- ↑ Fügedi 1986c, p. IV.11..

- ↑ Engel 2001, p. 144.

- ↑ Rady 2000, pp. 146-147.

- ↑ Kontler 1999, p. 89-90.

- ↑ Rady 2000, pp. 108-109.

- ↑ Rady 2000, p. 108.

- ↑ Engel 2001, pp. 178-179.

- ↑ Engel 2001, p. 176.

- ↑ Fügedi 1998, p. 45.

- ↑ Fügedi 1998, p. 47.

- 1 2 Kontler 1999, p. 97.

- ↑ Engel 2001, pp. 159-160, 181.

- ↑ Fügedi 1998, p. 34.

- 1 2 3 Cartledge 2011, p. 40.

- ↑ Rady 2000, pp. 59-60.

- 1 2 3 Engel 2001, p. 175.

- ↑ Rady 2000, p. 89.

- 1 2 Makkai, László (2001). "Transylvania in the medieval Hungarian kingdom (896–1526): From the Mongol invasion to the Battle of Mohács: Romanian Voivodes and Cnezes, Nobles and Villeins". History of Transylvania, Volume I.: From the Beginnings to 1606. Columbia University Press. Retrieved 27 October 2014.

- ↑ Rady 2000, pp. 84, 89, 93.

- ↑ Rady 2000, pp. 89, 93.

- ↑ Makkai, László (2001). "Transylvania in the medieval Hungarian kingdom (896–1526): Transylvanian culture in the Middle Ages: Orthodox Romanians and Their Church Hierarchy". History of Transylvania, Volume I.: From the Beginnings to 1606. Columbia University Press. Retrieved 27 October 2014.

- ↑ Pop 2013, p. 169.

- 1 2 Fügedi 1986c, p. IV.10.

- ↑ Engel 2001, pp. 141, 179.

- ↑ Engel 2001, pp. 179-180.

- ↑ Engel 2001, p. 180.

- ↑ Fügedi 1986c, p. IV.12..

- ↑ Engel 2001, pp. 197-199.

- ↑ Engel 2001, p. 198.

- ↑ Kontler 1999, p. 102.

- ↑ Engel 2001, p. 200.

- ↑ Engel 2001, p. 210.

- ↑ Cartledge 2011, p. 44.

- ↑ Kontler 1999, p. 103.

- 1 2 Engel 2001, p. 205.

- ↑ Kontler 1999, p. 104.

- ↑ Rady 2000, p. 151.

- 1 2 Engel, Kristó & Kubinyi 1998, p. 172.

- 1 2 Engel, Kristó & Kubinyi 1998, p. 171.

- 1 2 Engel 2001, pp. 232-233.

- 1 2 Engel, Kristó & Kubinyi 1998, p. 187.

- 1 2 3 4 Rady 2000, p. 155.

- 1 2 3 Engel, Kristó & Kubinyi 1998, p. 173.

- ↑ Engel, Kristó & Kubinyi 1998, pp. 154, 173.

- ↑ Engel 2001, p. 278.

- ↑ Engel 2001, p. 279.

- ↑ Cartledge 2011, p. 48.

- ↑ Kontler 1999, p. 113.

- 1 2 3 Engel 2001, p. 281.

- ↑ Kontler 1999, pp. 113, 116.

- 1 2 3 4 Engel, Kristó & Kubinyi 1998, p. 195.

- 1 2 Kontler 1999, p. 116.

- ↑ Engel, Kristó & Kubinyi 1998, p. 196.

- ↑ Engel 2001, p. 339.

- ↑ Fügedi 1998, pp. 21-22.

- ↑ The Customary Law of the Renowned Kingdom of Hungary in Three Parts (1517) (1.39.), p. 105.

- ↑ Fügedi 1998, p. 26.

- ↑ Engel 2001, p. 340.

- 1 2 3 Engel 2001, p. 341.

- 1 2 Kontler 1999, p. 117.

- ↑ Engel 2001, pp. 288, 293.

- 1 2 3 Fügedi 1986c, p. IV.14.

- ↑ Engel 2001, pp. 298, 311.

- 1 2 Engel 2001, p. 348.

- ↑ Cartledge 2011, p. 69.

- ↑ Kontler 1999, p. 134.

- ↑ Engel 2001, p. 349.

- 1 2 Engel 2001, p. 350.

- ↑ Spiesz, Caplovic & Bolchazy 2006, p. 58.

- ↑ Kontler 1999, p. 135.

- ↑ The Customary Law of the Renowned Kingdom of Hungary in Three Parts (1517) (1.4.), p. 53.

- 1 2 Engel 2001, p. 351.

- ↑ Fügedi 1998, pp. 32, 34.

- ↑ Cartledge 2011, p. 70.

- 1 2 Cartledge 2011, p. 71.

- ↑ Kontler 1999, p. 133.

- ↑ Engel 2001, p. 362.

- ↑ Engel, Kristó & Kubinyi 1998, p. 363.

- ↑ Engel 2001, p. 364.

- ↑ Cartledge 2011, p. 72.

- 1 2 Engel 2001, p. 370.

- ↑ Kontler 1999, p. 139.

- ↑ Engel 2001, p. 371.

- 1 2 3 Szakály 1994, p. 85.

- 1 2 Cartledge 2011, p. 83.

- ↑ Spiesz, Caplovic & Bolchazy 2006, p. 64.

- 1 2 Cartledge 2011, p. 94.

- ↑ Cartledge 2011, pp. 91-92.

- ↑ Cartledge 2011, pp. 87-88.

- ↑ Szakály 1994, p. 88.

- 1 2 Szakály 1994, p. 89.

- 1 2 Cartledge 2011, p. 91.

- ↑ Kontler 1999, p. 167.

- ↑ Kontler 1999, pp. 165-166, 171-172.

- 1 2 Pálffy 2009, pp. 72-73.

- ↑ Szakály 1994, pp. 91-92.

- ↑ Kontler 1999, p. 151.

- 1 2 Murdock 2000, p. 12.

- ↑ Murdock 2000, p. 20.

- ↑ Szakály 1994, p. 90.

- ↑ Cartledge 2011, p. 98.

- ↑ Szakály 1994, p. 92.

- ↑ Pálffy 2009, p. 231.

- ↑ Pálffy 2009, pp. 75-77.

- 1 2 Pálffy 2009, p. 87.

- ↑ Pálffy 2009, pp. 86-88.

- ↑ Pálffy 2009, p. 87, Figure 3.

- 1 2 Cartledge 2011, p. 97.

- ↑ Pálffy 2009, pp. 269-270.

- ↑ Pálffy 2009, pp. 110, 269-270.

- 1 2 Pálffy 2009, p. 178.

- ↑ Pálffy 2009, pp. 179-180.

- ↑ Mikuláš Teich, Roy Porter, The National question in Europe in historical context , Cambridge University Press, 1993, p.255

- ↑ Nakazawa 2007.

- ↑ Thompson 2014, p. 383.

- ↑ 1947. évi IV. törvény egyes címek és rangok megszüntetéséről (in Hungarian)

- ↑ 2007. évi LXXXII. törvény (in Hungarian)

- ↑ Templomot, iskolát a magyarságért (in Hungarian)

- ↑ T/1954 Az egyes címek és rangok megszüntetéséről szóló 1947. évi IV. törvény módosításáról (in Hungarian)

- ↑ Iromány adatai: 2010- T/1954 Az egyes címek és rangok megszüntetéséről szóló 1947. évi IV. törvény módosításáról. (in Hungarian) Last access: March 05, 2011

- ↑ Alkotmány: újjászületnek a vármegyék (in Hungarian)

Sources

Primary sources

- Anonymus, Notary of King Béla: The Deeds of the Hungarians (Edited, Translated and Annotated by Martyn Rady and László Veszprémy) (2010). In: Rady, Martyn; Veszprémy, László; Bak, János M. (2010); Anonymus and Master Roger; CEU Press; ISBN 978-963-9776-95-1.

- Constantine Porphyrogenitus: De Administrando Imperio (Greek text edited by Gyula Moravcsik, English translation by Romillyi J. H. Jenkins) (1967). Dumbarton Oaks Center for Byzantine Studies. ISBN 0-88402-021-5.

- Simon of Kéza: The Deeds of the Hungarians (Edited and translated by László Veszprémy and Frank Schaer with a study by Jenő Szűcs) (1999). CEU Press. ISBN 963-9116-31-9.

- The Chronicle of Regino of Prüm (2009). In: History and Politics in Late Carolingian and Ottonian Europe: The Chronicle of Regino of Prüm and Adalbert of Magdeburg (Translated and annotated by Simon MacLean); Manchester University Press; ISBN 978-0-7190-7135-5.

- The Customary Law of the Renowned Kingdom of Hungary in Three Parts (1517) (Edited and translated by János M. Bak, Péter Banyó and Martyn Rady, with an introductory study by László Péter) (2005). Charles Schlacks, Jr.; Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University. ISBN 1-884445-40-3.

- The Laws of the Medieval Kingdom of Hungary, 1000–1301 (Translated and edited by János M. Bak, György Bónis, James Ross Sweeney with an essay on previous editions by Andor Czizmadia, Second revised edition, In collaboration with Leslie S. Domonkos) (1999). Charles Schlacks, Jr. Publishers.

- The Taktika of Leo VI (Text, translation, and commentary by George T. Dennis) (2010). Dumbarton Oaks. ISBN 978-0-88402-359-3.

Secondary sources

- Bak, János (1993). ""Linguistic pluralism" in Medieval Hungary". In Meyer, Marc A. The Culture of Christendom: Essays in Medieval History in Memory of Denis L. T. Bethel. The Hambledon Press. pp. 269–280. ISBN 1-85285-064-7.

- Balassa, Iván, ed. (1997). Magyar Néprajz IV. [Hungarian ethnography IV.]. Akadémiai Kiadó. ISBN 963-05-7325-3.

- Berend, Nora; Urbańczyk, Przemysław; Wiszewski, Przemysław (2013). Central Europe in the High Middle Ages: Bohemia, Hungary and Poland, c. 900-c. 1300. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-78156-5.

- Cartledge, Bryan (2011). The Will to Survive: A History of Hungary. C. Hurst & Co. ISBN 978-1-84904-112-6.

- Engel, Pál; Kristó, Gyula; Kubinyi, András (1998). Magyarország története, 1301-1526 [The History of Hungary, 1301-1526]. Osiris Kiadó. ISBN 963-379-171-5.

- Engel, Pál (2001). The Realm of St Stephen: A History of Medieval Hungary, 895–1526. I.B. Tauris Publishers. ISBN 1-86064-061-3.

- Fügedi, Erik (1986a). Castle and Society in Medieval Hungary (1000-1437). Akadémiai Kiadó. ISBN 963-05-3802-4.

- Fügedi, Erik (1986b). Ispánok, bárók, kiskirályok [Counts, Barons and Kinglets]. Magvető Könyvkiadó. ISBN 963-14-0582-6.

- Fügedi, Erik (1986c). "The aristocracy in medieval Hungary (theses)". In Bak, J. M. Kings, Bishops, Nobles and Burghers in Medieval Hungary. Variorum Reprints. pp. IV.1–IV.14. ISBN 0-86078-177-1.

- Fügedi, Erik (1998). The Elefánthy: The Hungarian Nobleman and His Kindred (Edited by Damir Karbić, with a foreword by János M. Bak). Central European University Press. ISBN 963-9116-20-3.

- Fügedi, Erik; Bak, János M. (2012). "Foreign knights and clerks in Early Medieval Hungary". In Berend, Nora. The Expansion of Central Europe in the Middle Ages. Ashgate. pp. 319–331. ISBN 978-1-4094-2245-7.

- Georgescu, Vlad (1991). The Romanians: A History. Ohio State University Press. ISBN 0-8142-0511-9.

- Karácsony, János (1985). Magyarország egyháztörténete főbb vonásaiban 970-től 1900-ig [The Major Features of the Church History of Hungary from 970 until 1900]. Budapest: Könyvértékesítő Vállalat. ISBN 963-02-3434-3.

- Kontler, László (1999). Millennium in Central Europe: A History of Hungary. Atlantisz Publishing House. ISBN 963-9165-37-9.

- Kristó, Gyula (1998). Magyarország története, 895-1301 [The History of Hungary, 895-1301] (in Hungarian). Osiris Kiadó. ISBN 963-379-442-0.

- Lukačka, Ján (2011). "The beginnings of the nobility in Slovakia". In Teich, Mikuláš; Kováč, Dušan; Brown, Martin D. Slovakia in History. Cambridge University Press. pp. 30–37. ISBN 978-0-521-80253-6.

- Makkai, László (1994). "The Hungarians' prehistory, their conquest of Hungary, and their raids to the West to 955; The foundation of the Hungarian Christian state, 950–1196; Transformation into a Western-type state, 1196–1301". In Sugar, Peter F.; Hanák, Péter; Frank, Tibor. A History of Hungary. Indiana University Press. pp. 8–33. ISBN 963-7081-01-1.

- Murdock, Graeme (2000). Calvinism on the Frontier, 1600-1660: International Calvinims and the Reformed Church in Hungary and Transylvania. Clarrendon Press. ISBN 0-19-820859-6.

- Niederhauser, Emil (1993). "The national question in Hungary (translated from Hungarian by Mari Markus Gömöri)". In Teich, Mikuláš; Porter, Roy. The National Question in Europe in Historical Context. Cambridge University Press. pp. 248–269. ISBN 0-521-36713-1.

- Pálffy, Géza (2009). The Kingdom of Hungary and the Habsburg Monarchy in the Sixteenth Century. Center for Hungarian Studies and Publications. ISBN 978-0-88033-633-8.

- Pop, Ioan-Aurel (2013). "De manibus Valachorum scismaticorum...": Romanians and Power in the Mediaeval Kingdom of Hungary: The Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries. Peter Lang Edition. ISBN 978-3-631-64866-7.

- Rady, Martyn (2000). Nobility, Land and Service in Medieval Hungary. Palgrave. ISBN 0-333-80085-0.

- Nakazawa, Tatsuya (2007). "Slovak Nation as a Corporate Body: The Process of the Conceptual Transformation of a Nation without History into a Constitutional Subject during the Revolutions of 1848/49". In Hayashi, Tadayuki; Fukuda, Hiroshi. Regions in Central and Eastern Europe: Past and Present. Slavic Research Center, Hokkaido University. pp. 155–181. ISBN 978-4-938637-43-9.

- Spiesz, Anton; Caplovic, Dusan; Bolchazy, Ladislaus J. (2006). Illustrated Slovak History: A Struggle for Sovereignty in Central Europe. Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers. ISBN 978-0-86516-426-0.

- Szakály, Ferenc (1994). "The Early Ottoman Period, Including Royal Hungary, 1526-1606". In Sugar, Peter F.; Hanák, Péter; Frank, Tibor. A History of Hungary. Indiana University Press. pp. 83–99. ISBN 963-7081-01-1.

- Thompson, Wayne C. (2014). Nordic, Central, and Southeastern Europe 2014. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 9781475812244.

- Wolf, Mária (2008). A borsodi földvár (PDF). Művelődési Központ, Könyvtár és Múzeum, Edelény. ISBN 978-963-87047-3-3.

Further reading

- Tötösy de Zepetnek, Steven (2010). Nobilitashungariae: List of Historical Surnames of the Hungarian Nobility / A magyar történelmi nemesség családneveinek listája. Purdue University Press. ISSN 1923-9580.

.svg.png)