Zarmanochegas

Zarmanochegas (Ζαρμανοχηγὰς; according to Strabo[1]) or Zarmarus (according to Dio Cassius[2]) was a gymnosophist (naked philosopher), a monk of the Sramana tradition (possibly, but not necessarily a Buddhist) who, according to ancient historians such as Strabo and Dio Cassius, met Nicholas of Damascus in Antioch while Augustus (died 14 AD) was ruling the Roman Empire, and shortly thereafter proceeded to Athens where he burnt himself to death.[3][4] He is estimated to have died c. 22/21 BC.

Pandion Mission

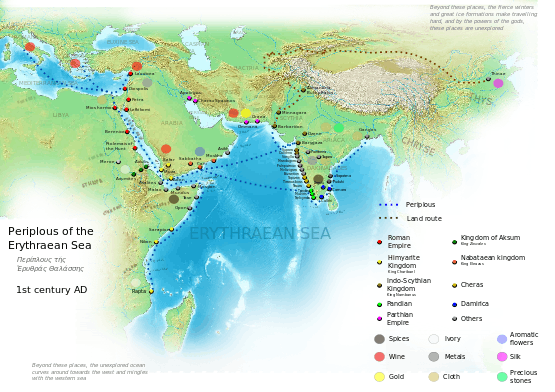

Nicolaus of Damascus describes an embassy sent by the "Indian king Porus (or Pandion, Pandya or Pandita (Buddhism)) to Caesar Augustus. The embassy traveled with a diplomatic letter on a skin in Greek. One of its members was a sramana who burned himself alive in Athens to demonstrate his faith. Nicholas of Damascus met the embassy at Antioch (near present day Antakya in Turkey) and this is related by Strabo (XV,1,73 ) and Dio Cassius (liv, 9). The monk's self-immolation made a sensation and was quoted by Strabo[5] and Dio Cassius (Hist 54.9).[6] His tomb indicated he came from Barygaza which is now Bharuch city of Gujarat, then the capital of Gaikwar near the north bank of the Narmada River; the name being derived from one of the ancient Rishis (Bhrigu) who lived there.[7] If the Sramana timed his death to match the arrival of Augustus in Athens then the date would be the winter of 22/21 BC when Augustus crossed from Sicily to Greece to visit Athens (Dio Cassius LIV,7, 2-3).[8] In support of this Priaulx notes that the poet Horace alludes to an Indian mission (Carmen Seculare 55, 56 (written 17 BC), Ode 14, L.iv (13 BC) and Ode 12, L. i (22 BC)). Priaulx also notes that later writers such as Florus (110 AD) (Hist. Rome IV C 12) and Suetonius (190 AD) (Augustus C21) refer to this Indian mission.[9] Augustus in his Ancyra inscription notes that "to me were sent embassies of kings from India, who had never been seen in the camp of any Roman general."[10]

Self-Immolation and Tomb in Athens

A tomb was made to the sramana, still visible in the time of Plutarch,[11] which bore the mention "ΖΑΡΜΑΝΟΧΗΓΑΣ ΙΝΔΟΣ ΑΠΟ ΒΑΡΓΟΣΗΣ" (Zarmanochēgas indos apo Bargosēs – Zarmanochegas, Indian from Bargosa").[12]

Strabo's (died 24 AD) account at Geographia xv,i,4 is as follows:

"From one place in India, and from one king, namely, Pandion, or, according to others, Porus, presents and embassies were sent to Augustus Caesar. With the ambassadors came the Indian Gymnosophist, who committed himself to the flames at Athens, like Calanus, who exhibited the same spectacle in the presence of Alexander."

Strabo adds (at xv, i, 73)

"To these accounts may be added that of Nicolaus Damascenus. This writer states that at Antioch, near Daphne, he met with ambassadors from the Indians, who were sent to Augustus Caesar. It appeared from the letter that several persons were mentioned in it, but three only survived, whom he says he saw. The rest had died chiefly in consequence of the length of the journey. The letter was written in Greek upon a skin; the import of it was, that Porus was the writer, that although he was sovereign of six hundred kings, yet that he highly esteemed the friendship of Cæsar; that he was willing to allow him a passage through his country, in whatever part he pleased, and to assist him in any undertaking that was just. Eight naked servants, with girdles round their waists, and fragrant with perfumes, presented the gifts which were brought. The presents were a Hermes (i. e. a man) born without arms, whom I have seen, large snakes, a serpent ten cubits in length, a river tortoise of three cubits in length, and a partridge larger than a vulture. They were accompanied by the person, it is said, who burnt himself to death at Athens. This is the practice with persons in distress, who seek escape from existing calamities, and with others in prosperous circumstances, as was the case with this man. For as everything hitherto had succeeded with him, he thought it necessary to depart, lest some unexpected calamity should happen to him by continuing to live; with a smile, therefore, naked, anointed, and with the girdle round his waist, he leaped upon the pyre. On his tomb was this inscription:

Dio Cassio's (died 235 AD) later account reads:

"For a great many embassies came to him, and the people of India, who had already made overtures, now made a treaty of friendship, sending among other gifts tigers, which were then for the first time seen by the Romans, as also, I think by the Greeks...One of the Indians, Zarmarus, for some reason wished to die, — either because, being of the caste of sages, he was on this account moved by ambition, or, in accordance with the traditional custom of the Indians, because of old age, or because he wished to make a display for the benefit of Augustus and the Athenians (for Augustus had reached Athens);— he was therefore initiated into the mysteries of the two goddesses, which were held out of season on account, they say, of Augustus, who also was an initiate, and he then threw himself alive into the fire.[15]"

Based on the different ways Strabo and Dio Cassio render the name (Zarmanochegas, Zarmarus), modern scholars attempted at interpreting Strabo's version as a combination of two words carrying additional information (see below under "Interpretation of the inscription in regard to religious affiliation"), this raising the question of the state of the tomb inscription at different times in the past.

The Eleusinian Mysteries (Ἐλευσίνια Μυστήρια) were initiation ceremonies of pre-historic antiquity focused on immortality and held in honour of Demeter and Persephone based at Eleusis in ancient Greece. Augustus became an initiate in 22/21BC and again in 19BC (Cassius Dio 51,4.1 and 54,9.10).[16] The later Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius also was initiated into the Eleusinian Mysteries in Athens.[17]

Plutarch (died 120 AD) in his Life of Alexander, after discussing the self-immolation of Calanus of India (Kalanos) writes:

"The same thing was done long after by another Indian who came with Caesar to Athens, where they still show you "the Indian's Monument."[18]

Interpretation of the inscription in regard to religious affiliation

Charles Eliot in his Hinduism and Buddhism: An Historical Sketch (1921) considers that the name Zarmanochegas "perhaps contains the two words Sramana and Acarya."[19] McCrindle (2004) infers from this that Zarmanochegas was a Buddhist priest or ascetic.[20][21]

HL Jones (2006) interprets the inscription as mentioned by Strabo and sees two words at the beginning, instead of one name:

"The Sramana master, an Indian, a native of Bargosa, having immortalized himself according to the custom of his country, lies here."[22]

Groskurd (1833) refers to Zarmanochegas as 'Zarmanos Chanes' and as an 'Indian wiseman' ('indischer Weiser').[23]

Priaulx (1873) translates the name in Sanskrit as çramanakarja ("teacher of Shamans") and adds "which points him out as of the Buddhist faith and a priest, and, as his death proves, a priest earnest in his faith.[24]

Halkias (2015) situates Zarmanochegas within a lineage of Buddhist sramanas who had adopted the custom of setting themselves on fire. [25]

Ancient Roman knowledge of Indian monk's lifestyle

Clement of Alexandria (died AD 215) in his Stromata (Bk I, Ch XV), after noting how philosophy flourished in antiquity amongst the "barbarians", states

"The Indian gymnosophists are also in the number, and the other barbarian philosophers. And of these there are two classes, some of them called Sarmanæ and others Brahmins. And those of the Sarmanæ who are called "Hylobii" neither inhabit cities, nor have roofs over them, but are clothed in the bark of trees, feed on nuts, and drink water in their hands. Like those called Encratites in the present day, they know not marriage nor begetting of children. Some, too, of the Indians obey the precepts of Buddha (Βούττα) whom, on account of his extraordinary sanctity, they have raised to divine honours."[26]

References

- ↑ http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Strabo/15A3*.html#ref116

- ↑ http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Strabo/15A3*.html#ref116

- ↑ Strabo, xv, 1, on the immolation of the Sramana in Athens (Paragraph 73).

- ↑ Dio Cassius, liv, 9.

- ↑ Strabo, xv, 1, on the immolation of the Sramana in Athens (Paragraph 73).

- ↑ Dio Cassius, liv, 9.

- ↑ JW McCrindle. Ancient India as Described in Classical Literature. Elibron Classics. Adamant Media Corp. 2005 ISBN 1-4021-6154-9 p 78 fn2 https://books.google.com/books?id=Hjfo-0ytFh0C&pg=PA78&lpg=PA78&dq=zarmanochegas&source=bl&ots=59GDNAecGN&sig=Zjtiv47h2iFeAQe9QsBGzs148qA&hl=en&sa=X&ei=MjnRULXfMu-TiAe5m4HwCg&ved=0CDoQ6AEwAzgK#v=onepage&q=zarmanochegas&f=false (accessed 18 Dec 2012)

- ↑ Huff ML. Civil Disobedience and Unrest in Augustan Athens Hesperia 1989; 58: 267-276.

- ↑ Osmond de Beauvoir Priaulx. The Indian Travels of Apollonius of Tyana and the Indian Embassies, London 1873, pp67 et seq.

- ↑ Evelyn Schuckburgh. Augustus. London 1903 Appendix 31.

- ↑ Plutarch. 'Life of Alexander' in The Lives of the Noble Grecians and Romans. (trans John Dryden and revised Arthur Hugh Clough) The Modern Library (Random House Inc). New York.p850

- ↑ Elledge CD. Life After Death in Early Judaism. Mohr Siebeck Tilbringen 2006 ISBN 3-16-148875-X pp122-125

- ↑ Strabo, xv, 1.73.

- ↑ http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Strabo/15A3*.html#ref116

- ↑ Dio Cassius, liv, 9.

- ↑ KW Arafat. Pausanius' Greece: Ancient Artists and Roman Rulers. Cambridge University Press. 1996 ISBN 0521553407 p 122.

- ↑ Gregory Hays "Introduction' in Marcus Aurelius. Meditations. Weidenfeld & Nicolson. London. 2003. ISBN 1-84212-675-X p xvii

- ↑ Plutarch. 'Life of Alexander' in The Lives of the Noble Grecians and Romans. (trans John Dryden and revised Arthur Hugh Clough) The Modern Library (Random House Inc). New York. p850

- ↑ Charles Eliot. Hinduism and Buddhism: An Historical Sketch vol 1. Curzon Press, Richmond 1990. p 431 fn 4.

- ↑ McCrindle JW. The Invasion of India by Alexander the Great. Kessinger Publishing. Montana 2004. p 389. https://books.google.com/books?id=ncDFRgtSysIC&pg=PA389&lpg=PA389&dq=zarmanochegas&source=bl&ots=74bHScngFu&sig=lSSOiLr9YGksOMiAMu2YcZdVzNI&hl=en&sa=X&ei=GpvHUIGCNKyeiAfehIGgCg&sqi=2&ved=0CEoQ6AEwBA#v=onepage&q=zarmanochegas&f=false (accessed 12 December 2012)

- ↑ JW McCrindle. Ancient India as Described in Classical Literature. Elibron Classics. Adamant Media Corp. 2005 ISBN 1-4021-6154-9 p 78 fn1 https://books.google.com/books?id=Hjfo-0ytFh0C&pg=PA78&lpg=PA78&dq=zarmanochegas&source=bl&ots=59GDNAecGN&sig=Zjtiv47h2iFeAQe9QsBGzs148qA&hl=en&sa=X&ei=MjnRULXfMu-TiAe5m4HwCg&ved=0CDoQ6AEwAzgK#v=onepage&q=zarmanochegas&f=false (accessed 18 Dec 2012)

- ↑ Elledge CD. Life After Death in Early Judaism. Mohr Siebeck Tilbringen 2006 ISBN 3-16-148875-X p125

- ↑ Christoph Gottleib Groskurd. Strabons Erdbeschreibung. Berlin und Stettin. 1833 p470

- ↑ Osmond de Beauvoir Priaulx. The Indian Travels of Apollonius of Tyana and the Indian Embassies London 1873 p78.

- ↑ “The Self-immolation of Kalanos and other Luminous Encounters among Greeks and Indian Buddhists in the Hellenistic world.” Journal of the Oxford Centre for Buddhist Studies, Vol. VIII, 2015: 163-186.

- ↑ Clement of Alexandria Stromata. BkI, Ch XV http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/anf02.vi.iv.i.xv.html (Accessed 19 Dec 2012)