Leonard P. Zakim Bunker Hill Memorial Bridge

| Zakim Bunker Hill Bridge | |

|---|---|

|

(2005) | |

| Coordinates | 42°22′08″N 71°03′48″W / 42.36889°N 71.06333°WCoordinates: 42°22′08″N 71°03′48″W / 42.36889°N 71.06333°W |

| Carries |

10 lanes of |

| Crosses | Charles River, MBTA Orange Line |

| Locale | Boston, Massachusetts |

| Official name | Leonard P. Zakim Bunker Hill Memorial Bridge |

| Owner | Commonwealth of Massachusetts |

| Maintained by | Massachusetts Department of Transportation |

| Characteristics | |

| Design | Hybrid Steel and Concrete Cable-stayed bridge[1] |

| Total length | 1,432 ft (436 m) |

| Width | 183 ft (56 m) |

| Height | 270 ft (82 m)[1] |

| Longest span | 745 ft (227 m) |

| Clearance below | 40 ft (12 m)[2] |

| History | |

| Construction cost | $105 million[3] |

| Opened |

March 30, 2003 (northbound) December 20, 2003 (southbound)[2] |

Leonard P. Zakim Bunker Hill Memorial Bridge (Massachusetts) | |

The Leonard P. Zakim (/ˈzeɪkəm/) Bunker Hill Memorial Bridge (or Zakim Bridge) is a cable-stayed bridge across the Charles River in Boston, Massachusetts. It is a replacement for the Charlestown High Bridge, an older truss bridge constructed in the 1950s. Of ten lanes, using the harp-style system of nearly-parallel cable layout, coupled with the use of "cradles" through each pylon for the cables, the main portion of the Zakim Bridge carries four lanes each way (northbound and southbound) of the Interstate 93 and U.S. Route 1 concurrency between the Thomas P. "Tip" O'Neill Jr. Tunnel and the elevated highway to the north. Two additional lanes are cantilevered outside the cables, which carry northbound traffic from the Sumner Tunnel and North End on-ramp. These lanes merge with the main highway north of the bridge. I-93 heads toward New Hampshire as the "Northern Expressway", and US 1 splits from the Interstate and travels northeast toward Massachusetts' North Shore communities, crossing the Mystic River via the Tobin Bridge.

The bridge and connecting tunnel were built as part of the Big Dig, the largest highway construction project in the United States. The northbound lanes were finished in March 2003, and the southbound lanes in December. The bridge's unique styling quickly became an icon for Boston, often featured in the backdrop of national news channels, to establish location, and included on tourist souvenirs. The bridge is commonly referred to as the "Zakim Bridge" or "Bunker Hill Bridge" by residents of nearby Charlestown.

The Leverett Circle Connector Bridge was constructed in conjunction with the Zakim Bridge, allowing some traffic to bypass it.

Design

In a cable-stayed bridge, instead of hanging the roadbed from cables slung between towers, the cables run directly between the roadbed and the towers. Although cable-stayed bridges have been common in Europe since World War II, they are relatively new to North America.

The bridge concept was developed by Swiss civil engineer Christian Menn and its design was engineered by American civil engineer Ruchu Hsu with Parsons Brinckerhoff. Wallace Floyd Associates, sub-consultants to Bechtel/Parsons Brinckerhoff, was the lead architect/urban designer and facilitated community participation during the design process.[4][5] The engineer of record is HNTB/FIGG. The lead designers were Theodore Zoli (from HNTB) and W. Denney Pate (from FIGG). The bridge follows a new design in which, besides having its eight primary lanes running through the towers, a pair of northbound lanes are cantilevered outside of the cable-stays. It has a striking, graceful appearance that is meant to echo the tower of the Bunker Hill Monument, which is within view of the bridge, and the white cables evoke imagery of the rigging of the USS Constitution, docked nearby.

The 1975-built MBTA Orange Line's Haymarket North Extension tunnel lies beneath the bridge.

Name

The bridge's full name commemorates Boston civic leader and civil rights activist Leonard P. Zakim who championed "building bridges between peoples",[6] and the Battle of Bunker Hill. Originally, Massachusetts Governor A. Paul Cellucci sought to name it the "Freedom Bridge". In 2000, however, local clergy and religious leaders, including Cardinal Bernard Francis Law, requested the Zakim name shortly after Zakim's death from myeloma. Although Cellucci agreed to the naming, community leaders from Charlestown objected to the name as they felt that since the design reflected the nearby Bunker Hill memorial, it should be named the "Bunker Hill Freedom bridge". Allegations of antisemitism were leveled against members of the mostly white, Irish Catholic community as reasons for resistance to the Zakim name, based on some comments quoted in the Boston Globe. Several local neo-Nazis also complained about the honor for Zakim and launched an unsuccessful petition drive to drop his name from the Bunker Hill one (the petition needed 100 signatures to be reviewed by the Massachusetts State Legislature and only 20 people signed it). In response, several community leaders spoke out against the allegations in a press conference, stating that the claims, made by Professor Jonathan Sarna, were his alone and did not reflect the community's historical (not racial) basis of favoring the "Bunker Hill" name, though they dodged questions about the false claim that no Jews had fought in the battle of Bunker Hill.[7]

Eventually a compromise between the Boston City Council, the Massachusetts State Legislature and community activists brought about the current name. As with the Hoover Dam, different communities call the bridge by different colloquial names. Many people in the Charlestown area refer to it as the "Bunker Hill Bridge", while most, including the local press and traffic monitoring services, refer to it as the "Zakim Bridge".

Landscape design and public art

Placement of footings for the Zakim Bridge required environmental permits to relocate areas of open water surface, changing the contour of the Charles River shoreline. The process of landscape design and environmental mitigation under the bridge deck and around the bridge supports allowed for the creation of a new and accessible public landscape designed by Carol R. Johnson Associates. This under bridge landscape contains a series of perforated stainless steel lighting-based public artworks, entitled, Five Beacons for the Lost Half Mile.

Pedestrians and cyclists are able to travel from Charlestown toward Cambridge over the adjacent North Bank Pedestrian Bridge to North Point Park (Cambridge, Massachusetts).[8] This bridge is a link in the Charles River Bike Path.

Dedication

The bridge was dedicated on October 4, 2002, in a ceremony held on the new span. The dedication speakers included members of Zakim's family, government officials, and a performance of the song Thunder Road by Bruce Springsteen.[9]

Introducing the song, Springsteen said about Zakim, "... I knew him a little bit during the last year of his life, he was one of those people whose, intensity, inner spirit you could feel even when he was very ill and uh. ... I guess, you know, we honor his memory obviously not with this beautiful bridge, very lovely, but by continuing on in his fight for social justice."[10]

Miscellaneous facts

- On Mother's Day of 2002, more than 200,000 people waited in long lines for a one-time only chance to walk on the bridge, almost a year before the structure was opened to vehicular traffic.[11]

- On October 14, 2002, fourteen elephants from the Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Circus, weighing a total of 112,000 pounds (51,000 kg), were walked across the bridge to "test" it. (In the nineteenth century, elephants were sometimes used to test bridges—such as the Eads Bridge in St. Louis and the Brooklyn Bridge in New York City[12]—not only because of their great weight, but because of a superstition that elephants had a special instinct preventing them from setting foot on unsafe structures.)[13]

- Although the bridge was completed in 2002, it was not opened to traffic until the northbound Central Artery tunnel opened in early 2003. The southbound lanes were opened in December 2003, with the opening of the southbound tunnel, and the cantilevered northbound lanes (a two-lane entrance ramp) opened in April 2005, when the old bridge was improved. It acts as a complete replacement for the previous three-lane, dual-height steel bridge, the Charlestown High Bridge. The different heights of the lanes of the I-93 elevated highway in Charlestown are the only remaining hints to the layout of the old bridge.

- In March 2005, ice fell off the cables and landed on the roadway below in large enough chunks to possibly break windshields, or even endanger motorists, stopping traffic.[14]

- The Travel Channel ranked the Zakim Bridge 9th in their list of the World's Top Ten Bridges. The article also points out that, at the time of publication, the bridge was the widest cable-stayed bridge in the world, but with only 10 lanes for traffic.[15]

Gallery

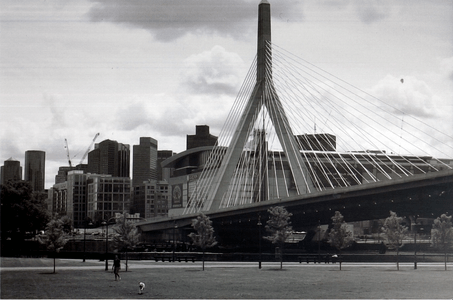

Bridge and downtown Boston from Paul Revere Park

Bridge and downtown Boston from Paul Revere Park Detail of the cabling and tower on the bridge

Detail of the cabling and tower on the bridge A view from the roadway

A view from the roadway- A view from the roadway traveling south into Boston

Traffic stopped on bridge and proximity to TD Garden

Traffic stopped on bridge and proximity to TD Garden View from Paul Revere Park in Charlestown

View from Paul Revere Park in Charlestown The bridge from below

The bridge from below

See also

References

- 1 2 Massachusetts Department of Transportation. "MassDOT — The Big Dig — Tunnels and Bridges — The Cable-stayed Bridge". Retrieved 2014-04-05.

- 1 2 Eastern Roads. "Leonard P Zakim-Bunker Hill Memorial Bridge (I-93 and US 1)". Retrieved 2006-10-19.

- ↑ "Leonard P Zakim-Bunker Hill Memorial Bridge (I-93 and US 1)". Retrieved 4 October 2014.

- ↑ Thomas P. Hughes, Rescuing Prometheus, New York, Pantheon, 1998

- ↑ Wiley Online Library 19 June 2013, Megaproject Management" Lessons in Risk and Project Management from the Big Dig, pp. 415–418

- ↑ MTA press release (2002-09-18). "Leonard P. Zakim Bunker Hill Bridge Dedication Events Set For October 3–6". Archived from the original on February 10, 2007. Retrieved 2008-04-28.

"He worked tirelessly to build personal bridges between our city's diverse people and neighborhoods." - Joyce Zakim, wife of Lenny Zakim

- ↑ Biography of Lenny Zakim in articles and TV programs. "Lenny's Story: Cancer and the Quality of Life". the International Myeloma Foundation. Archived from the original on 2008-01-12. Retrieved 2008-04-29.

- ↑ "Twists & Turns Geometric constraints posed a major challenge for designers of a new footbridge" (PDF).

- ↑ "Bruce Springsteen performs at the Leonar (sic) P. Zakim Bunker Hill Bridge Dedication".

- ↑ "Brucebase transcription".

- ↑ DeLuca, Nick (2014-05-14). "This Day in Boston History: The Zakim Bridge Carries 200,000 Pedestrians". BostInno. Retrieved 2016-06-06.

- ↑ "The Pachyderm Test". Retrieved 2008-09-17.

- ↑ History Channel, This Day In HISTORY, June 14, 1874, "Test Elephant" Proves Eads Bridge Is Safe"

- ↑ Daniel, Mac; Globe Staff (2005-03-15). "Bridge's falling ice called fluke of nature". The Boston Globe. Retrieved 2006-10-19.

- ↑ Marathe, Amy. "World's Top Ten Bridges". The Travel Channel. Retrieved 2008-02-27.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Leonard P. Zakim Bunker Hill Memorial Bridge. |

- The Leonard P. Zakim Bunker Hill Bridge web site

- Fact sheet on the Leonard P. Zakim Bunker Hill Bridge

- Leonard P. Zakim Bunker Hill Bridge at Structurae

- Description and history on bostonroads.com

- Zakim bridge as viewed from former location of Spaulding Rehab Hospital

- Leonard P. Zakim Bunker Hill Memorial Bridge | foundations

- Zakim Bridge architect pays to keep the lights on

- Bland Zakim Bridge leaves us feeling blue

- MassDOT Reveals Zakim Bridge New Lighting

- New Lighting Revealed for Zakim Bunker Hill Bridge

- A new type of Cape escape, and a Zakim unveiling

- Lawrence model bridge builders meet their role model

- The Leonard P. Zakim Bunker Hill Bridge – Philips Color Kinetics Case Study