ZX Spectrum software

The ZX Spectrum software library currently consists of more than 24,000 titles.[1] Despite the fact that the ZX Spectrum hardware was limited by most standards, its software library was very diverse, including programming language implementations (C,[2] Pascal,[3] Prolog,[4] Forth[5]), several Z80 assemblers/disassemblers (e.g.: OCP Editor/Assembler, HiSoft Devpac, ZEUS Assembler, Artic Assembler), Sinclair BASIC compilers (e.g.: MCoder, COLT, HiSoft BASIC, ToBoS-FP), Sinclair BASIC extensions (e.g.: Beta BASIC, Mega Basic), databases (e.g.: VU-File[6]), word processors (e.g.: Tasword II[7]), spread sheets (e.g.: VU-Calc[6]), drawing and painting tools (e.g.: OCP Art Studio,[8] The Artist, Paintbox, Melbourne Draw), even 3D modelling (VU-3D[9][10]), and, of course, many, many games.

Software distribution media and copy protection

Tape

Basis

Because most British home computer owners used tape instead of disk storage into the mid-1980s,[11] most Spectrum software was originally distributed on audio cassette tapes. The software was encoded on tape as a sequence of pulses that may sound similar to the sounds of a modern-day modem. Since ZX Spectrum had only a rudimentary tape interface, data was recorded using an unusually simple and very reliable modulation, similar to pulse-width modulation but without a constant clock rate. Pulses of different widths (durations) represent 0s and 1s. A "zero" is represented by a ~244 μs pulse followed by a gap of the same duration (855 clock ticks each at 3.5 MHz) for a total ~489 μs;[12] "one" is twice as long, totaling ~977 μs. This allows for 1023 "ones" or 2047 "zeros" to be recorded per second. Assuming an even proportion of each, the resulting average speed was ~1535 bit/s. Higher speeds were possible using custom machine code loaders instead of the ROM routines.

Naturally, a standard 48K program would take about 5 minutes to load: 49152 bytes × 8 = 393216 bits; 393216 bits / 1535 baud ≈ 256 seconds = 4:16 minutes. In reality, however, a 48K program usually took between 3–4 minutes to load (because of different number of 0s and 1s encoded using pulse-width modulation, and not all memory needs loading), and 128K programs could take up to 11:23 minutes to load. Experienced users could often tell the type of a file, e.g. file header, screen image or main block of code, from the way it sounded on the tape.[13]

Standard format and loader

The standard method of storing files on tape used pilot signals, headers, and data blocks. Pilot signals are used to calibrate the system to the speed of the tape, both in terms of how it was written and of natural slight variations between different tape decks. Headers have a short file size of 19 bytes (17 for header information, 1 for flag and 1 for checksum), and the loader generally presents one of these messages depending on their type: Program: <filename> for programs written in BASIC; Bytes: <filename> for machine code, screen dumps, etc.; or Character array: <filename> for an ASCII-encoded file.[14]

During standard loading and saving processes, the border flashes with cyan/red stripes for the pilot signal and yellow/blue stripes for the header and data blocks; which colour of the pair is used depends upon the bit that was last read from the tape. Pilot signals are usually represented with a thick stripe size; on header and data blocks, the stripes are thinner (depending the baudrate). Striped border effects, as used in the standard loader or more complex ones (see below) can also be found on games written for other 8-bit computers, such as the Amstrad CPC 464/664/6128 (which, as it used the same CPU, often received ports of loading routines originally for the Spectrum) and the Commodore C64/128.

Reliability

The Spectrum was intended to work with almost any cassette tape player, and despite differences in audio reproduction fidelity, the software loading process was designed to be reliable; nevertheless it was still possible for tapes to fail loading with the message R Tape loading error, 0:1. One common cause was the use of a cassette copy from a tape recorder with a different head alignment to the one being used. This could sometimes be fixed by pressing on the top of the player during loading, or wedging the cassette with pieces of folded paper, to physically shift the tape into the required alignment. A more reliable solution was to realign the head, which was easily accessible on a number of tape players, with a small (jeweller's) screwdriver.

Typical settings for loading were ¾ volume, 100% treble, 0% bass. Audio filters like loudness and Dolby Noise Reduction had to be disabled, and it was not recommended to use a Hi-Fi player to load programs. There were some tape recorders built specially for digital use, such as the Timex Computer 2010 Tape Recorder or Grundig CR 100 Data Recorder. The ZX Spectrum Plus 2 and 2A models are fashioned after an Amstrad CPC 464 and feature a built-in tape "datacorder".

Custom loaders and copying

It is possible to alter the colours between which the border alternates during loading, and/or to use more than two colours, in order to obtain more flashy visual effects during the loading process.

Complex loaders with unusual speeds or encoding were the basis of the ZX Spectrum copy protection schemes, although other methods were used including asking for a particular word from the documentation included with the game — often a novella — or the notorious Lenslok system. This had a set of plastic prisms in a fold-out plastic holder: the idea was that a scrambled two-letter code would appear on the screen, which could only be read by holding the prisms at a fixed distance from the screen courtesy of the plastic holder. This relied rather too much on everyone using the same size television, and Lenslok became a running joke with Spectrum users.

One very interesting kind of software was copiers. Most were copyright infringement oriented, and their function was only tape duplication, but when Sinclair Research launched the ZX Microdrive, copiers were developed to copy programs from audio tape to microdrive tapes, and later on diskettes. Best known were the Lerm suite produced by Lerm Software and Trans Express by Romantic Robot. As the protections became more complex (e.g. Speedlock) it was almost impossible to use copiers to copy tapes, and the loaders had to be cracked by hand, to produce unprotected versions. Special hardware, like Romantic Robot's Multiface which was able to dump a copy of the ZX Spectrum RAM to disk/tape at the press of a button, was developed, entirely circumventing the copy protection systems. "Snapshots" generated by these black boxes would later become the original filetype recognised by emulators - .SNA - although these memory dumps have been generally replaced by more complex files, incorporating original loading features and multi-level options.

ZX Microdrive

The ZX Microdrive system was released in July 1983 and quickly became quite popular with the Spectrum user base due to the low cost of the drives, however, the actual media was very expensive for software publishers to use for mass market releases (by a factor of 10, compared to tape duplication). Furthermore, the cartridges themselves acquired a reputation for unreliability, and publishers were reluctant to QA each and every item shipped.[15] Hence the main use became to complement tape releases, usually utilities and niche products like the Tasword word processing software and the aforementioned Trans Express. No games are known to be exclusively released on Microdrive, but some companies allowed, and even aided, their software to be copied over. One such example was Rally Driver by Five Ways Software Ltd.[15]

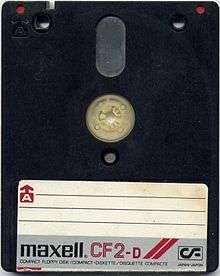

Floppy disk

Several floppy disk systems were designed for the ZX Spectrum. The most popular (excepting Eastern Europe,) were the DISCiPLE and +D systems released by Miles Gordon Technology in 1987 and 1988 respectively. Despite becoming popular and being reliable (from using standard Shugart disk drives), most releases were utility software. However, both systems had the ability to store memory images onto disk, snapshots, which later on could be loaded back into the ZX Spectrum and execution would commence from the point where they were "snapped", making them perfect for "backups". Both systems were also compatible with the Microdrive command syntax, which made porting existing software simpler.

The ZX Spectrum +3 featured a built-in 3" disk drive and enjoyed more success when it came to commercial software releases - more than 700[1] titles were released on disk from 1987 to 1997.

Most Russian releases since 1989 are made for the Beta 128 disc interface, the only system now in use there.

Others

In addition, software was also distributed through print media, fan magazines and books. The prevalent language for distribution was the Spectrum's BASIC dialect Sinclair BASIC. The reader would type the software into the computer by hand, run it, and save it to tape for later use. The software distributed in this way was in general simpler and slower than its assembly language counterparts, and lacked graphics. But soon, magazines were printing long lists of checksummed hexadecimal digits with machine code games or tools. There was a vibrant scientific community built around such software, ranging from satellite dish alignment programs to school classroom scheduling programs.

One unusual software distribution method were radio or television shows in e.g. Croatia (Radio 101), Serbia (Ventilator 202), Slovenia (Radio Študent), Poland, Czechoslovakia, Romania, Lebanon or Brazil, where the host would describe a program, instruct the audience to connect a cassette tape recorder to the radio or TV and then broadcast the program over the airwaves in audio format. In former Soviet Union, mostly in Russia and Ukraine unauthorised radio operators (so-called radio hooligans) often exchanged software from cassette tapes for Spectrum and other popular computers by broadcasting it.

Another unusual method which was used by some magazines were 7" 33⅓ rpm "flexidisc" records, not the hard vinyl ones, which could be played on a standard record player. These disks were known under various trademarked names including "Floppy ROM", "Flexisoft", and "Discoflex".

Spectrum software in popular music

A few pop musicians included Sinclair programs on their records. The Buzzcocks front man, Pete Shelly, put a Spectrum program including lyrics and other information as the last track on his XL-1 album. The punk band Inner City Unit put a Spectrum database of band information on their 1984 release, 'New Anatomy'. Also in 1984, the Thompson Twins released a game on vinyl.[16] The Freshies had a brief flirtation with fame and Spectrum games, and the Aphex Twin included various loading noises on his Richard D. James album in 1996—most notably part of the loading screen from Sabre Wulf on Carn Marth. Shakin' Stevens included his Shaky Game at the end of his The Bop Won't Stop album. The aim of the game was to guide your character around a maze, while avoiding bats. Upon completion your score would be given in terms of a rank of disc, e.g. "gold" or "platinum". The game had a minor connection with one of his tracks, It's Late. Scottish band Urusei Yatsura included a Spectrum program that showed a satanic message in the beginning of the song Thank You (from the album Everybody Loves Urusei Yatsura).

There was also a music program for the Spectrum 48K which allowed to play two notes at a time, by rapidly switching between the waveforms of the two separate notes, a big improvement over the mono Spectrum sound. The program was branded after the popular '80s pop band Wham!, and some of the biggest hits of this group could be played with the Spectrum. The program was called Wham! The Music Box and released by Melbourne House, one of the most prolific publishing houses at the time.

Spectrum software today

As audio tapes have a limited shelf-life, most Spectrum software has been digitized in recent years and is available for download in digital form. The legality of this practice is still in question. However, it seems unlikely that any action will ever be taken over such so-called "abandonware".

One popular program for digitizing Spectrum software is Taper: it allows connecting a cassette tape player to the line in port of a sound card or, through a simple home-built device, to the parallel port of a PC.[17] Once in digital form, the software can be executed on one of many existing emulators, on virtually any platform available today. Today, the largest on-line archive of ZX Spectrum software is World of Spectrum, with more than 24,000 titles.

The Spectrum enjoys a vibrant, dedicated fan-base. Since it was cheap and simple to learn to use and program, the Spectrum was the starting point for many programmers and technophiles who remember it with nostalgia. The hardware limitations of the Spectrum imposed a special level of creativity on game designers, and for this reason, many Spectrum games are very creative and playable even by today's standards. Games for the ZX Spectrum continue to be developed and released long after the machine itself was discontinued.

ZX Spectrum games continue to inspire developers and gamers on modern platforms such as iOS with many games being produced using similar styles of game-play mechanics to those from the ZX Spectrum era.

Notable titles

Your Sinclair top 10

Between October 1991 and February 1992 Your Sinclair published a list of what they considered to be the top 100 games for the ZX Spectrum. Their top 10 were:[18][19]

- Deathchase

- Rebelstar

- All or Nothing

- Stop the Express

- Head Over Heels

- R-Type

- The Sentinel

- Rainbow Islands

- Boulder Dash

- Tornado Low Level

CRASH top 10

Between August and December 1991 CRASH published their list of the top 100 ZX Spectrum games, including in the top 10:[20]

- Rainbow Islands

- Chase H.Q.

- RoboCop

- RoboCop 2

- Dizzy

- Target: Renegade

- Magicland Dizzy

- Batman: The Movie

- Operation Wolf

- Midnight Resistance

In CRASH's Top 10 all but the Dizzy games were published by Ocean Software. All but one of the Your Sinclair Top 10 games were released in 1987 or before (the conversion of Rainbow Islands did not appear until 1989, although the original was released in 1987), in comparison to the CRASH Top 10 which exclusively features games released in 1987 or after. 1987 was the year in which use of the newer 128K architecture and of the newer AY-3-8912 sound chip began to take off. All of CRASH's Top 10, with the exception of Dizzy, made use of these new features with enhanced sound and preloaded levels (eliminating the need for a multi-load), reflecting a difference in the attitudes of the editorship and readership of the two magazines.

Techradar's "Top 30"

Techradar published their list of the best 30 ZX Spectrum games in 2012, underlining which games stood the test of time.[21]

- Elite – Firebird Games

- R-Type – Electric Dreams Software

- Chuckie Egg - A'n'F Software

- Manic Miner - Bug-Byte Software Ltd

- Knight Lore - Ultimate Play the Game

- Back to Skool - Microsphere

- Football Manager - Addictive Games Ltd

- Lunar Jetman - Ultimate Play the Game

- Horace Goes Skiing – Beam Software

- Boulder Dash – Front Runner

- Sim City - Infogrames

- Underwurlde - Ultimate Play the Game

- Super Hang-On - Electric Dreams Software

- Jet Set Willy - Software Projects Ltd

- Rainbow Islands - Ocean Software Ltd

- Tornado Low Level - Vortex Software

- Ant Attack - Quicksilva Ltd

- Chase H.Q. - Ocean Software Ltd

- Deus Ex Machina - Automata UK Ltd

- Lode Runner - Software Projects Ltd

- Gauntlet - US Gold Ltd

- Fantasy World Dizzy - Code Masters Ltd

- The Hobbit - Melbourne House

- Atic Atac - Ultimate Play the Game

- Tetris - Mirrorsoft Ltd

- Hyper Sports - Imagine Software Ltd

- The Way of the Exploding Fist – Melbourne House

- Daley Thompson's Decathlon - Ocean

- Skool Daze - Microsphere

- The Great Escape - Ocean

Notable Spectrum developers

A number of current leading games developers and development companies began their careers on the ZX Spectrum. David Perry of Shiny Entertainment wrote Three Weeks in Paradise and Paperboy II. Tim and his brother Chris Stamper, along with Tim’s girlfriend (later wife) Carole Ward and John Lathbury, published Jetpac, Atic Atac, Sabre Wulf and Knightlore - and many others, as Ultimate Play the Game, now known as Rare, maker of many famous titles for Nintendo and Xbox game consoles.[22] Alan Cox wrote Blizzard Pass, and is an ardent supporter of open source software.[23]

Other notable Spectrum game developers include:

- Jonathan "Joffa" Smith wrote Cobra, Hysteria, Firefly and a conversion from the Green Beret arcade among other games which prove that smooth scrolling was never a problem on the ZX Spectrum, as long as the developer had the necessary technical knowledge.

- Matthew Smith wrote the seminal Spectrum titles Manic Miner and Jet Set Willy, proving that it was possible to have continual music during game play on a Spectrum;

- Nigel Alderton was the 16 year old author of Chuckie Egg, published by A'n'F Software on the Spectrum and BBC Micro;

- The first author of an isometric 3D game - Ant Attack, published by Quicksilva, was Sandy White;

- Julian Gollop wrote Rebelstar and Laser Squad;

- Jon Ritman was the author of Match Day and Head Over Heels;

- The Oliver Twins wrote the Dizzy series of games;

- David and Helen Reidy wrote Skool Daze and Back to Skool for Microsphere;

- Christian Penfold and Mel Croucher, of Automata, authors of Pimania, My Name Is Uncle Groucho, You Win A Fat Cigar and Deus Ex Machina;[24]

- Paul Owens and Christian Urquhart, developers of Daley Thompson's Decathlon for Ocean Software;

- Philip Mitchell and Veronika Megler of Beam Software, who wrote The Hobbit published by Melbourne House;

- Lode Runner (Software Projects) authors David J Anderson and Ian Morrison;

- Costa Panayi, who wrote Android, Android 2, Highway Encounter, Cyclone and Tornado Low Level for Vortex Software;

- Peter Liepa and Chris Gray wrote Boulder Dash for First Star Software;

- William Tang wrote the Horace series of games (Hungry Horace, Horace Goes Skiing and Horace and the Spiders) for Beam Software, published by Sinclair Research and Melbourne House.

See also

References

- 1 2 Heide, Martijn van der. "Archive!". World of Spectrum. Retrieved 22 July 2012.

- ↑ Heide, Martijn van der. "Sinclair Infoseek: HiSoft C". World of Spectrum. Retrieved 2006-08-24.

- ↑ Heide, Martijn van der. "Sinclair Infoseek: HiSoft Pascal 4". World of Spectrum. Retrieved 2006-08-24.

- ↑ Heide, Martijn van der. "Sinclair Infoseek: Micro-Prolog". World of Spectrum. Retrieved 2006-08-24.

- ↑ Heide, Martijn van der. "Sinclair Infoseek: Forth". World of Spectrum. Retrieved 2006-08-24.

- 1 2 Pearce, Nick (October–November 1982). "Zap! Pow! Boom!". ZX Computing: 75.

- ↑ Wetherill, Steven (June 1984). "Tasword Two: The Word Processor". CRASH! (5): 126.

- ↑ Gilbert, John (October 1985). "Art Studio". Sinclair User (43): 28. Retrieved 2007-01-18.

- ↑ Carter, Alasdair (October–November 1983). "VU-3D". ZX Computing: 76–77.

- ↑ "Psion Vu-3D". Retrieved 2007-01-18.

- ↑ Pountain, Dick (January 1985). "The Amstrad CPC 464". BYTE. p. 401. Retrieved 27 October 2013.

- ↑ Heide, Martijn van der; Kopanske, Martin; Kac, Tomaz (1997–1999). "Selecting a sample rate". Tape decoding with Taper. Retrieved 2006-08-24.

- ↑ "Loader Bollocks". gaminglives.com.

- ↑ Heide, Martijn van der; et al. (2005). "48K ZX Spectrum Technical Information". comp.sys.sinclair FAQ. Retrieved 2013-09-22.

- 1 2 "Microdrive revisited". CRASH (22). November 1985. Retrieved 2006-08-10.

- ↑ Heide, Martijn van der. "Sinclair Infoseek: Thompson Twins Adventure, The". World of Spectrum. Retrieved 2006-08-24.

- ↑ http://www.worldofspectrum.org/taper.html

- ↑ "The YS Top 100 Speccy Games Of All Time (Ever!)". Your Sinclair (73): 34–36. January 1992. Retrieved 2006-08-15.

- ↑ "The YS Top 100 Speccy Games Of All Time Pt 5". Your Sinclair (74): 45. February 1992. Retrieved 2006-08-15.

- ↑ "All Time Encyclopedia Top 100 Speccy Games". CRASH (94): 45–48. December 1991. Retrieved 2006-08-15.

- ↑ Hartley, Adam (23 April 2012). "30 best ZX Spectrum games". Retrieved 2016-03-21.

- ↑ Maher, Jimmy (2014-01-14). "The Legend of Ultimate Play the Game". The Digital Antiquarian.

- ↑ Bezroukov, Nikolai. "Alan Cox: and the Art of Making Beta Code Work". Portraits of Open Source Pioneers. Retrieved 2007-01-18.

- ↑ Maher, Jimmy (2014-01-21). "The Merry Pranksters of Automata". The Digital Antiquarian.