Wetting

Wetting is the ability of a liquid to maintain contact with a solid surface, resulting from intermolecular interactions when the two are brought together. The degree of wetting (wettability) is determined by a force balance between adhesive and cohesive forces. Wetting deals with the three phases of materials: gas, liquid, and solid. It is now a center of attention in nanotechnology and nanoscience studies due to the advent of many nanomaterials in the past two decades (e.g. graphene,[1] carbon nanotube, boron nitride nanomesh[2]).

Wetting is important in the bonding or adherence of two materials.[3] Wetting and the surface forces that control wetting are also responsible for other related effects, including capillary effects.

There are two types of wetting: non-reactive wetting and active wetting.[4][5]

Explanation

Adhesive forces between a liquid and solid cause a liquid drop to spread across the surface. Cohesive forces within the liquid cause the drop to ball up and avoid contact with the surface.

| Contact angle | Degree of wetting |

Strength of: | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Solid/liquid interactions |

Liquid/liquid interactions | ||

| θ = 0 | Perfect wetting | strong | weak |

| 0 < θ < 90° | high wettability | strong | strong |

| weak | weak | ||

| 90° ≤ θ < 180° | low wettability | weak | strong |

| θ = 180° | perfectly non-wetting | weak | strong |

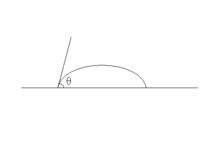

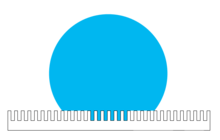

The contact angle (θ), as seen in Figure 1, is the angle at which the liquid–vapor interface meets the solid–liquid interface. The contact angle is determined by the result between adhesive and cohesive forces. As the tendency of a drop to spread out over a flat, solid surface increases, the contact angle decreases. Thus, the contact angle provides an inverse measure of wettability.[6]

A contact angle less than 90° (low contact angle) usually indicates that wetting of the surface is very favorable, and the fluid will spread over a large area of the surface. Contact angles greater than 90° (high contact angle) generally means that wetting of the surface is unfavorable, so the fluid will minimize contact with the surface and form a compact liquid droplet.

For water, a wettable surface may also be termed hydrophilic and a nonwettable surface hydrophobic. Superhydrophobic surfaces have contact angles greater than 150°, showing almost no contact between the liquid drop and the surface. This is sometimes referred to as the "Lotus effect". The table describes varying contact angles and their corresponding solid/liquid and liquid/liquid interactions.[7] For nonwater liquids, the term lyophilic is used for low contact angle conditions and lyophobic is used when higher contact angles result. Similarly, the terms omniphobic and omniphilic apply to both polar and apolar liquids.

High-energy vs. low-energy surfaces

Liquids can interact with two main types of solid surfaces. Traditionally, solid surfaces have been divided into high-energy solids and low-energy types. The relative energy of a solid has to do with the bulk nature of the solid itself. Solids such as metals, glasses, and ceramics are known as 'hard solids' because the chemical bonds that hold them together (e.g., covalent, ionic, or metallic) are very strong. Thus, it takes a large input of energy to break these solids (alternatively large amount of energy is required to cut the bulk and make two separate surfaces so high surface energy), so they are termed “high energy”. Most molecular liquids achieve complete wetting with high-energy surfaces.

The other type of solids is weak molecular crystals (e.g., fluorocarbons, hydrocarbons, etc.) where the molecules are held together essentially by physical forces (e.g., van der Waals and hydrogen bonds). Since these solids are held together by weak forces, a very low input of energy is required to break them, thus they are termed “low energy”. Depending on the type of liquid chosen, low-energy surfaces can permit either complete or partial wetting.[8][9]

Dynamic surfaces have been reported that undergo changes in surface energy upon the application of an appropriate stimuli. For example, a surface presenting photon-driven molecular motors was shown to undergo changes in water contact angle when switched between bistable conformations of differing surface energies.[10]

Wetting of low-energy surfaces

Low-energy surfaces primarily interact with liquids through dispersion (van der Waals) forces. William Zisman had several key findings in the work that he did:[11]

Zisman observed that cos θ increases linearly as the surface tension (γLV) of the liquid decreased. Thus, he was able to establish a linear function between cos θ and the surface tension (γLV) for various organic liquids.

A surface is more wettable when γLV and θ is low. Zisman termed the intercept of these lines when cos θ = 1, as the critical surface tension (γc) of that surface. This critical surface tension is an important parameter because it is a characteristic of only the solid.

Knowing the critical surface tension of a solid, it is possible to predict the wettability of the surface.[6] The wettability of a surface is determined by the outermost chemical groups of the solid. Differences in wettability between surfaces that are similar in structure are due to differences in packing of the atoms. For instance, if a surface has branched chains, it will have poorer packing than a surface with straight chains.

Ideal solid surfaces

An ideal surface is flat, rigid, perfectly smooth, and chemically homogeneous, and has zero contact angle hysteresis. Zero hysteresis implies the advancing and receding contact angles are equal. In other words, only one thermodynamically stable contact angle exists. When a drop of liquid is placed on such a surface, the characteristic contact angle is formed as depicted in Fig. 1. Furthermore, on an ideal surface, the drop will return to its original shape if it is disturbed.[7][11] The following derivations apply only to ideal solid surfaces; they are only valid for the state in which the interfaces are not moving and the phase boundary line exists in equilibrium.

Minimization of energy, three phases

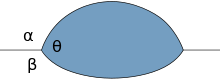

Figure 3 shows the line of contact where three phases meet. In equilibrium, the net force per unit length acting along the boundary line between the three phases must be zero. The components of net force in the direction along each of the interfaces are given by:

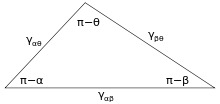

where α, β, and θ are the angles shown and γij is the surface energy between the two indicated phases. These relations can also be expressed by an analog to a triangle known as Neumann’s triangle, shown in Figure 4. Neumann’s triangle is consistent with the geometrical restriction that , and applying the law of sines and law of cosines to it produce relations that describe how the interfacial angles depend on the ratios of surface energies.[12]

Because these three surface energies form the sides of a triangle, they are constrained by the triangle inequalities, γij < γjk + γik meaning that no one of the surface tensions can exceed the sum of the other two. If three fluids with surface energies that do not follow these inequalities are brought into contact, no equilibrium configuration consistent with Figure 3 will exist.

Simplification to planar geometry, Young's relation

If the β phase is replaced by a flat rigid surface, as shown in Figure 5, then β = π, and the second net force equation simplifies to the Young equation,[13]

which relates the surface tensions between the three phases: solid, liquid and gas. Subsequently, this predicts the contact angle of a liquid droplet on a solid surface from knowledge of the three surface energies involved. This equation also applies if the "gas" phase is another liquid, immiscible with the droplet of the first "liquid" phase.

Real smooth surfaces and the Young contact angle

The Young equation assumes a perfectly flat and rigid surface often referred to as an ideal surface. In many cases, surfaces are far from this ideal situation, and two are considered here: the case of rough surfaces and the case of smooth surfaces that are still real (finitely rigid). Even in a perfectly smooth surface, a drop will assume a wide spectrum of contact angles ranging from the so-called advancing contact angle, , to the so-called receding contact angle, . The equilibrium contact angle () can be calculated from and as was shown by Tadmor[15] as,

where

The Young–Dupré equation and spreading coefficient

The Young–Dupré equation (Thomas Young 1805; Anthanase Dupré and Paul Dupré 1869) dictates that neither γSG nor γSL can be larger than the sum of the other two surface energies.[16][17] The consequence of this restriction is the prediction of complete wetting when γSG > γSL + γLG and zero wetting when γSL > γSG + γLG. The lack of a solution to the Young–Dupré equation is an indicator that there is no equilibrium configuration with a contact angle between 0 and 180° for those situations.[18]

A useful parameter for gauging wetting is the spreading parameter S,

When S > 0, the liquid wets the surface completely (complete wetting). When S < 0, partial wetting occurs.

Combining the spreading parameter definition with the Young relation yields the Young–Dupré equation:

which only has physical solutions for θ when S < 0.

Nonideal rough solid surfaces

.jpg)

Unlike ideal surfaces, real surfaces do not have perfect smoothness, rigidity, or chemical homogeneity. Such deviations from ideality result in phenomenon called contact-angle hysteresis, which is defined as the difference between the advancing (θa) and receding (θr) contact angles[19]

In simpler terms, contact angle hysteresis is essentially the displacement of a contact line such as the one in Figure 3, by either expansion or retraction of the droplet. Figure 6 depicts the advancing and receding contact angles. The advancing contact angle is the maximum stable angle, whereas the receding contact angle is the minimum stable angle. Contact-angle hysteresis occurs because many different thermodynamically stable contact angles are found on a nonideal solid. These varying thermodynamically stable contact angles are known as metastable states.[11]

Such motion of a phase boundary, involving advancing and receding contact angles, is known as dynamic wetting. When a contact line advances, covering more of the surface with liquid, the contact angle is increased and generally is related to the velocity of the contact line.[20] If the velocity of a contact line is increased without bound, the contact angle increases, and as it approaches 180°, the gas phase will become entrained in a thin layer between the liquid and solid. This is a kinetic nonequilibrium effect which results from the contact line moving at such a high speed that complete wetting cannot occur.

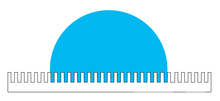

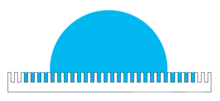

A well-known departure from ideality is when the surface of interest has a rough texture. The rough texture of a surface can fall into one of two categories: homogeneous or heterogeneous. A homogeneous wetting regime is where the liquid fills in the roughness grooves of a surface. A heterogeneous wetting regime, though, is where the surface is a composite of two types of patches. An important example of such a composite surface is one composed of patches of both air and solid. Such surfaces have varied effects on the contact angles of wetting liquids. Cassie–Baxter and Wenzel are the two main models that attempt to describe the wetting of textured surfaces. However, these equations only apply when the drop size is sufficiently large compared with the surface roughness scale.[21] When the droplet size is comparable to that of the underlying pillars, the effect of line tension should be considered. .[22]

Wenzel's model

The Wenzel model (Robert N. Wenzel 1936) describes the homogeneous wetting regime, as seen in Figure 7, and is defined by the following equation for the contact angle on a rough surface:[21]

where is the apparent contact angle which corresponds to the stable equilibrium state (i.e. minimum free energy state for the system). The roughness ratio, r, is a measure of how surface roughness affects a homogeneous surface. The roughness ratio is defined as the ratio of true area of the solid surface to the apparent area.

θ is the Young contact angle as defined for an ideal surface. Although Wenzel's equation demonstrates the contact angle of a rough surface is different from the intrinsic contact angle, it does not describe contact angle hysteresis.[23]

Cassie–Baxter model

When dealing with a heterogeneous surface, the Wenzel model is not sufficient. A more complex model is needed to measure how the apparent contact angle changes when various materials are involved. This heterogeneous surface, like that seen in Figure 8, is explained using the Cassie–Baxter equation (Cassie's law):[21]

Here the rf is the roughness ratio of the wet surface area and f is the fraction of solid surface area wet by the liquid. It is important to realize that when f = 1 and rf = r, the Cassie–Baxter equations becomes the Wenzel equation. On the other hand, when there are many different fractions of surface roughness, each fraction of the total surface area is denoted by .

A summation of all fi equals 1 or the total surface. Cassie–Baxter can also be recast in the following equation:[24]

Here γ is the Cassie–Baxter surface tension between liquid and vapor, the γi,sv is the solid vapor surface tension of every component and γi,sl is the solid liquid surface tension of every component. A case that is worth mentioning is when the liquid drop is placed on the substrate and creates small air pockets underneath it. This case for a two-component system is denoted by:[24]

Here the key difference to notice is that there is no surface tension between the solid and the vapor for the second surface tension component. This is because of the assumption that the surface of air that is exposed is under the droplet and is the only other substrate in the system. Subsequently, the equation is then expressed as (1 – f). Therefore, the Cassie equation can be easily derived from the Cassie–Baxter equation. Experimental results regarding the surface properties of Wenzel versus Cassie–Baxter systems showed the effect of pinning for a Young angle of 180 to 90°, a region classified under the Cassie–Baxter model. This liquid/air composite system is largely hydrophobic. After that point, a sharp transition to the Wenzel regime was found where the drop wets the surface, but no further than edges of the drop.

Precursor film

With the advent of high resolution imaging, researchers have started to obtain experimental data which have led them to question the assumptions of the Cassie–Baxter equation when calculating the apparent contact angle. These groups believe the apparent contact angle is largely dependent on the triple line. The triple line, which is in contact with the heterogeneous surface, cannot rest on the heterogeneous surface like the rest of the drop. In theory, it should follow the surface imperfection. This bending in triple line is unfavorable and is not seen in real-world situations. A theory that preserves the Cassie–Baxter equation while at the same time explaining the presence of minimized energy state of the triple line hinges on the idea of a precursor film. This film of submicrometer thickness advances ahead of the motion of the droplet and is found around the triple line. Furthermore, this precursor film allows the triple line to bend and take different conformations that were originally considered unfavorable. This precursor fluid has been observed using environmental scanning electron microscopy (ESEM) in surfaces with pores formed in the bulk. With the introduction of the precursor film concept, the triple line can follow energetically feasible conformations and thereby correctly explaining the Cassie–Baxter model.[25]

"Petal effect" vs. "lotus effect"[26]

The intrinsic hydrophobicity of a surface can be enhanced by being textured with different length scales of roughness. The red rose takes advantage of this by using a hierarchy of micro- and nanostructures on each petal to provide sufficient roughness for superhydrophobicity. More specifically, each rose petal has a collection of micropapillae on the surface and each papilla, in turn, has many nanofolds. The term “petal effect” describes the fact that a water droplet on the surface of a rose petal is spherical in shape, but cannot roll off even if the petal is turned upside down. The water drops maintain their spherical shape due to the superhydrophobicity of the petal (contact angle of about 152.4°), but do not roll off because the petal surface has a high adhesive force with water.

When comparing the "petal effect" to the "lotus effect", it is important to note some striking differences. The surface structure of the lotus leaf and the rose petal, as seen in Figure 9, can be used to explain the two different effects. The lotus petal has a randomly rough surface and low contact angle hysteresis, which means the water droplet is not able to wet the microstructure spaces between the spikes. This allows air to remain inside the texture, causing a heterogeneous surface composed of both air and solid. As a result, the adhesive force between the water and the solid surface is extremely low, allowing the water to roll off easily (i.e. "self-cleaning" phenomenon).

The rose petal's micro- and nanostructures are larger in scale than those of the lotus leaf, which allows the liquid film to impregnate the texture. However, as seen in Figure 9, the liquid can enter the larger-scale grooves, but it cannot enter into the smaller grooves. This is known as the Cassie impregnating wetting regime. Since the liquid can wet the larger-scale grooves, the adhesive force between the water and solid is very high. This explains why the water droplet will not fall off even if the petal is tilted at an angle or turned upside down. This effect will fail if the droplet has a volume larger than 10 µl because the balance between weight and surface tension is surpassed.

Cassie–Baxter to Wenzel transition

In the Cassie–Baxter model, the drop sits on top of the textured surface with trapped air underneath. During the wetting transition from the Cassie state to the Wenzel state, the air pockets are no longer thermodynamically stable and liquid begins to nucleate from the middle of the drop, creating a “mushroom state” as seen in Figure 10.[27] The penetration condition is given by:

where

- θC is the critical contact angle

- Φ is the fraction of solid/liquid interface where drop is in contact with surface

- r is solid roughness (for flat surface, r = 1)

The penetration front propagates to minimize the surface energy until it reaches the edges of the drop, thus arriving at the Wenzel state. Since the solid can be considered an absorptive material due to its surface roughness, this phenomenon of spreading and imbibition is called hemiwicking. The contact angles at which spreading/imbibition occurs are between 0 and π/2.[28]

The Wenzel model is valid between θC and π/2. If the contact angle is less than ΘC, the penetration front spreads beyond the drop and a liquid film forms over the surface. Figure 11 depicts the transition from the Wenzel state to the surface film state. The film smoothes the surface roughness and the Wenzel model no longer applies. In this state, the equilibrium condition and Young's relation yields:

By fine-tuning the surface roughness, it is possible to achieve a transition between both superhydrophobic and superhydrophilic regions. Generally, the rougher the surface, the more hydrophobic it is.

Spreading dynamics

If a drop is placed on a smooth, horizontal surface, it is generally not in the equilibrium state. Hence, it spreads until an equilibrium contact radius is reached (partial wetting). While taking into account capillary, gravitational, and viscous contributions, the drop radius as a function of time can be expressed as[29]

For the complete wetting situation, the drop radius at any time during the spreading process is given by

where

- γLG = Surface tension of the fluid

- V = Drop volume

- η = Viscosity of the fluid

- ρ = Density of the fluid

- g = Gravitational constant

- λ = Shape factor λ = 37.1 m−1

- t0 = Experimental delay time

- re = Drop radius in the equilibrium

Modifying wetting properties

Surfactants

Many technological processes require control of liquid spreading over solid surfaces. When a drop is placed on a surface, it can completely wet, partially wet, or not wet the surface. By reducing the surface tension with surfactants, a nonwetting material can be made to become partially or completely wetting. The excess free energy (σ) of a drop on a solid surface is:[30]

- γ is the liquid–vapor interfacial tension

- γSL is the solid–liquid interfacial tension

- γSV is the solid–vapor interfacial tension

- S is the area of liquid–vapor interface

- P is the excess pressure inside liquid

- R is the radius of droplet base

Based on this equation, the excess free energy is minimized when γ decreases, γSL decreases, or γSV increases. Surfactants are absorbed onto the liquid–vapor, solid–liquid, and solid–vapor interfaces, which modify the wetting behavior of hydrophobic materials to reduce the free energy. When surfactants are absorbed onto a hydrophobic surface, the polar head groups face into the solution with the tail pointing outward. In more hydrophobic surfaces, surfactants may form a bilayer on the solid, causing it to become more hydrophilic. The dynamic drop radius can be characterized as the drop begins to spread. Thus, the contact angle changes based on the following equation:[30]

- θ0 is initial contact angle

- θ∞ is final contact angle

- τ is the surfactant transfer time scale

As the surfactants are absorbed, the solid–vapor surface tension increases and the edges of the drop become hydrophilic. As a result, the drop spreads.

Surface changes

Ferrocene is a redox-active organometallic compound[32] which can be incorporated into various monomers and used to make polymers which can be tethered onto a surface.[31] Vinylferrocene (ferroceneylethene) can be prepared by a Wittig reaction[33] and then polymerised to form polyvinylferrocene (PVFc), an analogue of polystyrene. Another polymer which can be formed is poly(2-(methacryloyloxy)ethyl ferrocenecarboxylate), PFcMA. Both PVFc and PFcMA have been tethered onto silica wafers and the wettability measured when the polymer chains are uncharged and when the ferrocene moieties are oxidised to produce positively charged groups, as illustrated at right.[31] The contact angle with water on the PFcMA-coated wafers was 70° smaller following oxidation, while in the case of PVFc the decrease was 30°, and the switching of wettability has been shown to be reversible. In the PFcMA case, the effect of longer chains with more ferrocene groups (and also greater molar mass) has been investigated, and it was found that longer chains produce significantly larger contact angle reductions.[31][34]

See also

References

- ↑ J Rafiee, X Mi, H Gullapalli, AV Thomas, F Yavari, Y Shi, PM Ajayan, NA Koratkar, Wetting transparency of graphene, Nature Materials 11 (3), 217-222.

- ↑ SFL Mertens, A Hemmi, S Muff, O Gröning, S De Feyter, J Osterwalder, T Greber, Switching stiction and adhesion of a liquid on a solid, Nature 534, 2016, 676–679.

- ↑ Amziane, Sofiane; Collet, Florence (2017-03-05). Bio-aggregates Based Building Materials: State-of-the-Art Report of the RILEM Technical Committee 236-BBM. Springer. ISBN 9789402410310.

- ↑ Dezellus, O. and N. Eustathopoulos (2010). "Fundamental issues of reactive wetting by liquid metals." Journal of Materials Science 45(16): 4256-4264.

- ↑ Han Hu, Hai-Feng Ji, and Ying Sun, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., 15, (2013) 16557

- 1 2 Sharfrin, E.; Zisman, William A. (1960). "Constitutive relations in the wetting of low energy surfaces and the theory of the retraction method of preparing monolayers". The Journal of Physical Chemistry. 64 (5): 519–524. doi:10.1021/j100834a002.

- 1 2 Eustathopoulos, N.; Nicholas, M.G.; Drevet B. (1999). Wettability at high temperatures. Oxford, UK: Pergamon. ISBN 0-08-042146-6.

- ↑ Schrader, M.E; Loeb, G.I. (1992). Modern Approaches to Wettability. Theory and Applications. New York: Plenum Press. ISBN 0-306-43985-9.

- ↑ de Gennes, P.G. (1985). "Wetting: statics and dynamics". Reviews of Modern Physics. 57 (3): 827–863. Bibcode:1985RvMP...57..827D. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.57.827.

- ↑ "Control of Surface Wettability Using Tripodal Light-activated Molecular Motors" Journal of the American Chemical Society, 3 February 2014 doi:10.1021/ja412110t

- 1 2 3 Johnson, Rulon E. (1993) in Wettability Ed. Berg, John. C. New York, NY: Marcel Dekker, Inc. ISBN 0-8247-9046-4

- ↑ Rowlinson, J.S.; Widom, B. (1982). Molecular Theory of Capillarity. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-855642-X.

- ↑ Young, T. (1805). "An Essay on the Cohesion of Fluids". Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. 95: 65–87. doi:10.1098/rstl.1805.0005.

- ↑ T. S. Chow (1998). "Wetting of rough surfaces". Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter. 10 (27): L445. Bibcode:1998JPCM...10L.445C. doi:10.1088/0953-8984/10/27/001.

- ↑ Tadmor, Rafael (2004). "Line energy and the relation between advancing, receding and Young contact angles". Langmuir. 20 (18): 7659–64. PMID 15323516. doi:10.1021/la049410h.

- ↑ Schrader, Malcolm E. (2002-05-01). "Young-Dupre Revisited". Langmuir. 11 (9): 3585–3589. doi:10.1021/la00009a049.

- ↑ Athanase M. Dupré, Paul Dupré (1869-01-01). Théorie mécanique de la chaleur (in French). Gauthier-Villars.

- ↑ Clegg, Carl (2016). "Contact Angle Spreading Coefficient". www.ramehart.com. ramé-hart. Retrieved 6 January 2016.

- ↑ Robert J. Good (1992). "Contact angle, wetting, and adhesion: a critical review". J. Adhesion Sci. Technol. 6 (12): 1269–1302. doi:10.1163/156856192X00629.

- ↑ De Gennes, P. G. (1994). Soft Interfaces. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-56417-4.

- 1 2 3 Abraham Marmur (2003). "Wetting of Hydrophobic Rough Surfaces: To be heterogeneous or not to be". Langmuir. 19 (20): 8343–8348. doi:10.1021/la0344682.

- ↑ Xuemei Chen, Ruiyuan Ma, Jintao Li, Chonglei Hao, Wei Guo, B.L.Luk, Shuaicheng Li, Shuhuai Yao, Zuankai Wang. The evaporation of droplets on superhydrophobic surfaces: Surface roughness and small droplet size effects. Physical Review Letters, 109, 116101 (2012).

- ↑ Marmur, Abraham (1992) in Modern Approach to Wettability: Theory and Applications Schrader, Malcolm E. and Loeb, George New York: Plenum Press

- 1 2 Whyman, G.; Bormashenko, Edward; Stein, Tamir (2008). "The rigirious derivation of Young, Cassie–Baxter and Wenzel equations and the analysis of the contact angle hysteresis phenomenon". Chemical Physics Letters. 450 (4–6): 355–359. Bibcode:2008CPL...450..355W. doi:10.1016/j.cplett.2007.11.033.

- ↑ Bormashenko, E. (2008). "Why does the Cassie–Baxter equation apply?". Colloids and Surface A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects. 324: 47–50. doi:10.1016/j.colsurfa.2008.13.025.

- ↑ Lin, F.; Zhang, Y; Xi, J; Zhu, Y; Wang, N; Xia, F; Jiang, L (2008). "Petal Effect: Two major examples of the Cassie–Baxter model are the "Petal Effect" and Lotus Effect". A superhydrophobic state with high adhesive force". Langmuir. 24 (8): 4114–4119. PMID 18312016. doi:10.1021/la703821h.

- 1 2 Ishino, C.; Okumura, K (2008). "Wetting transitions on textured hydrophilic surfaces". European Physical Journal. 25 (4): 415–424. Bibcode:2008EPJE...25..415I. PMID 18431542. doi:10.1140/epje/i2007-10308-y.

- ↑ Quere, D.; Thiele, Uwe; Quéré, David (2008). "Wetting of Textured Surfaces" (PDF). Colloids and Surfaces. 206 (1–3): 41–46. doi:10.1016/S0927-7757(02)00061-4.

- ↑ Härth M., Schubert D.W., Simple Approach for Spreading Dynamics of Polymeric Fluids, Macromol. Chem. Phys., 213, 654–665, 2012, DOI: 10.1002/macp.201100631

- 1 2 Lee, K. S.; Ivanova, N.; Starov, V. M.; Hilal, N.; Dutschk, V. (2008). "Kinetics of wetting and spreading by aqueous surfactant solutions". Advances in Colloid and Interface Science. 144 (1–2): 54–65. PMID 18834966. doi:10.1016/j.cis.2008.08.005.

- 1 2 3 4 Pietschnig, R. (2016). "Polymers with pendant ferrocenes". Chem. Soc. Rev. 45: 5216–5231. doi:10.1039/C6CS00196C.

- ↑ Connelly, N. G.; Geiger, W. E. (1996). "Chemical Redox Agents for Organometallic Chemistry". Chem. Rev. 96 (2): 877–910. PMID 11848774. doi:10.1021/cr940053x.

- ↑ Liu, W.-Y.; Xu, Q.-H.; Ma, Y.-X.; Liang, Y.-M.; Dong, N.-L.; Guan, D.-P. (2001). "Solvent-free synthesis of ferrocenylethene derivatives". J. Organomet. Chem. 625: 128–132. doi:10.1016/S0022-328X(00)00927-X.

- ↑ Elbert, J.; Gallei, M.; Rüttiger, C.; Brunsen, A.; Didzoleit, H.; Stühn, B.; Rehahn, M. (2013). "Ferrocene Polymers for Switchable Surface Wettability". Organometallics. 32 (20): 5873–5878. doi:10.1021/om400468p.

Further reading

- de Gennes, Pierre-Gilles; Brochard-Wyart, Françoise; Quéré, David (2004). Capillarity and Wetting Phenomena. Springer New York. ISBN 978-1-4419-1833-8. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-21656-0.

- Victor M. Starov; Manuel G. Velarde; Clayton J. Radke (2 April 2007). Wetting and Spreading Dynamics. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4200-1617-8.

External links

-

Media related to Wetting at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Wetting at Wikimedia Commons