Yohimbine

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Routes of administration | Oral |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 7-86% (mean 33%) |

| Biological half-life | 0.25-2.5 hours[1] |

| Excretion | Urine (as metabolites) |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.005.157 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

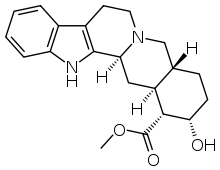

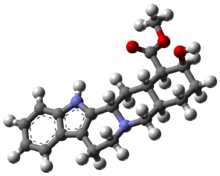

| Formula | C21H26N2O3 |

| Molar mass |

354.44 g/mol (base) 390.90 g/mol (hydrochloride) |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Yohimbine (/joʊˈhɪmbiːn/)[2] is an indole alkaloid derived from the bark of the Pausinystalia yohimbe tree in Central Africa. It is a veterinary drug used to reverse sedation in dogs and deer. Yohimbine has been studied as a potential treatment for erectile dysfunction but there is insufficient evidence to rate its effectiveness.[3] Extracts from yohimbe have been marketed as dietary supplements for improving sexual function.[4]

Uses

Yohimbine is a drug used in veterinary medicine to reverse the effects of xylazine in dogs and deer.[5]

Yohimbe extracts, which contain yohimbine, have been used in traditional medicine and marketed as dietary supplements.[4]

Toxicity

Depending on dosage, yohimbine can either increase or decrease systemic blood pressure (through vasoconstriction or vasodilation, respectively). Because yohimbine has highest affinity for the α2 receptor, small doses can increase blood pressure by causing a relatively selective α2 blockade. Yohimbine also, however, interacts with α1 receptors, albeit with lower affinity; therefore, at higher doses an α1 blockade can occur and overwhelm the effects of the α2 blockade, leading to a potentially dangerous drop in blood pressure.[6] Higher doses of oral yohimbine may create numerous side effects, such as rapid heart rate, overstimulation, anomalous blood pressure, cold sweating, and insomnia.

Extracts and chemistry

Yohimbe (Pausinystalia johimbe) is a tree that grows in western and central Africa;[7] yohimbine was originally extracted from the bark of yohimbe in 1896 by Adolph Spiegel.[8] In 1943 the correct constitution of yohimbine was proposed by Witkop.[9] Fifteen years later, Van Tamelen used a 23-step synthesis to become the first person to achieve the synthesis of yohimbine.[10][11][12]

Pharmacology

Yohimbine has high affinity for the α2-adrenergic receptor, moderate affinity for the α1 receptor, 5-HT1A, 5-HT1B, 5-HT1D, 5-HT1F, 5-HT2B, and D2 receptors, and weak affinity for the 5-HT1E, 5-HT2A, 5-HT5A, 5-HT7, and D3 receptors.[13][14] It behaves as an antagonist at α1-adrenergic, α2-adrenergic, 5-HT1B, 5-HT1D, 5-HT2A, 5-HT2B, and D2, and as a partial agonist at 5-HT1A.[13][15][16][17] Yohimbine interacts with serotonin and dopamine receptors in high concentrations.[18]

| Molecular Target | Binding Affinity (Ki in nanomolar)[19] | Pharmacologic Action [13][15][16][17][20] | Species | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SERT | 1,000 | Inhibitor | Human | Frontal Cortex |

| 5-HT1A | 346 | Partial Agonist | Human | Cloned |

| 5-HT1B | 19.9 | Antagonist | Human | Cloned |

| 5-HT1D | 44.3 | Antagonist | Human | Cloned |

| 5-HT1E | 1,264 | Unknown | Human | Cloned |

| 5-HT1F | 91.6 | Unknown | Human | Cloned |

| 5-HT2A | 1,822 | Antagonist | Human | Cloned |

| 5-HT2B | 143.7 | Antagonist | Human | Cloned |

| 5-HT7 | 2,850 | Unknown | Human | Cloned |

| α1A | 1,680 | Antagonist | Human | Cloned |

| α1B | 1,280 | Antagonist | Human | Cloned |

| α1C | 770 | Antagonist | Human | Cloned |

| α1D | 557 | Antagonist | Human | Cloned |

| α2A | 1.05 | Antagonist | Human | Cloned |

| α2B | 1.19 | Antagonist | Human | Cloned |

| α2C | 1.19 | Antagonist | Human | Cloned |

| D2 | 339 | Antagonist | Human | Cloned |

| D3 | 3,235 | Antagonist | Human | Cloned |

Research

Sexual dysfunction

Yohimbine has been studied as a potential treatment for erectile dysfunction but there is insufficient evidence to rate its effectiveness.[6][3] It is illegal in the United States to market an over the counter product containing yohimbine as a treatment for erectile dysfunction without getting FDA approval to do so.[21]

Yohimbine blocks the pre- and post-synaptic α2 receptors. Blockade of post-synaptic α2 receptors causes only minor corpus cavernosum smooth muscle relaxation, due to the fact that the majority of adrenoceptors in the corpus cavernosum are of the α1 type. Blockade of pre-synaptic α2 receptors facilitates the release of several neurotransmitters in the central and peripheral nervous system — thus in the corpus cavernosum — such as nitric oxide and norepinephrine. Whereas nitric oxide released in the corpus cavernosum is the major vasodilator contributing to the erectile process, norepinephrine is the major vasoconstrictor through stimulation of α1 receptors on the corpus cavernosum smooth muscle. Under physiologic conditions, however, nitric oxide attenuates norepinephrine vasoconstriction.[22]

See also

References

- ↑ Hedner, T; Edgar, B; Edvinsson, L; Hedner, J; Persson, B; Pettersson, A (1992). "Yohimbine pharmacokinetics and interaction with the sympathetic nervous system in normal volunteers". European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 43 (6): 651–656. PMID 1493849. doi:10.1007/BF02284967.

- ↑ yohimbine. (n.d.) Collins English Dictionary – Complete and Unabridged. (1991, 1994, 1998, 2000, 2003). Retrieved January 27, 2015 from http://www.thefreedictionary.com/yohimbine

- 1 2 Andersson KE (September 2001). "Pharmacology of penile erection". Pharmacological Reviews. 53 (3): 417–50. PMID 11546836.

- 1 2 Beille, P. E. (2013). "Scientific Opinion on the evaluation of the safety in use of Yohimbe (Pausinystalia yohimbe)". EFSA Journal. 11: 3302. doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2013.3302.

- ↑ 21 CFR Sec. 522.2670 Yohimbine

- 1 2 "Yohimbe: MedlinePlus Supplements". Medline. Retrieved 2013-05-26.

- ↑ Kew World Checklist of Selected Plant Families, Pausinystalia johimbe

- ↑ Year Book of the American Pharmaceutical Association. American Pharmaceutical Association. 1914. p. 564. Retrieved 2015-05-04.

- ↑ Witkop, B. (1943), Justus Liebigs Annalen der Chemie, 83: 554 Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ The Alkaloids: Chemistry and Pharmacology. Academic Press. 1988. p. 564. ISBN 0-12-469532-9.

- ↑ van Tamelen; E. E. (1958). "The Total Synthesis of Yohimbine". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 80: 5006–5007. doi:10.1021/ja01551a062.

- ↑ Herle, B. (2011). "Total Synthesis of (+)-Yohimbine via an Enantioselective Organocatalytic Pictet–Spengler Reaction". J. Org. Chem. 76: 8907–8912. doi:10.1021/jo201657n.

- 1 2 3 Millan MJ, Newman-Tancredi A, Audinot V, et al. (February 2000). "Agonist and antagonist actions of yohimbine as compared to fluparoxan at alpha(2)-adrenergic receptors (AR)s, serotonin (5-HT)(1A), 5-HT(1B), 5-HT(1D) and dopamine D(2) and D(3) receptors. Significance for the modulation of frontocortical monoaminergic transmission and depressive states". Synapse. 35 (2): 79–95. PMID 10611634. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(200002)35:2<79::AID-SYN1>3.0.CO;2-X.

- ↑ "PDSP Ki Database".

- 1 2 Arthur JM, Casañas SJ, Raymond JR (June 1993). "Partial agonist properties of rauwolscine and yohimbine for the inhibition of adenylyl cyclase by recombinant human 5-HT1A receptors". Biochemical Pharmacology. 45 (11): 2337–41. PMID 8517875. doi:10.1016/0006-2952(93)90208-E.

- 1 2 Kaumann AJ (June 1983). "Yohimbine and rauwolscine inhibit 5-hydroxytryptamine-induced contraction of large coronary arteries of calf through blockade of 5 HT2 receptors". Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Archives of Pharmacology. 323 (2): 149–54. PMID 6136920. doi:10.1007/BF00634263.

- 1 2 Baxter GS, Murphy OE, Blackburn TP (May 1994). "Further characterization of 5-hydroxytryptamine receptors (putative 5-HT2B) in rat stomach fundus longitudinal muscle". British Journal of Pharmacology. 112 (1): 323–31. PMC 1910288

. PMID 8032658. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.1994.tb13072.x.

. PMID 8032658. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.1994.tb13072.x. - ↑ "Yohimbine (PIM 567)". Inchem.org. Retrieved 2013-05-26.

- ↑ National Institute of Mental Health. "PDSP Ki Database". University of North Carolina. Archived from the original on November 8, 2013. Retrieved 5 July 2013.

- ↑ "Yohimbine". DrugBank. University of Alberta. Archived from the original on January 30, 2013. Retrieved 12 April 2014.

- ↑ FDA regulations on OTC products

- ↑ Saenz De Tejada, I; Kim, NN; Goldstein, I; Traish, AM (2000). "Regulation of pre-synaptic alpha adrenergic activity in the corpus cavernosum". International Journal of Impotence Research. 12 Suppl 1: S20–25. PMID 10845761. doi:10.1038/sj.ijir.3900500.