John Koukouzelis

| John Koukouzelis | |

|---|---|

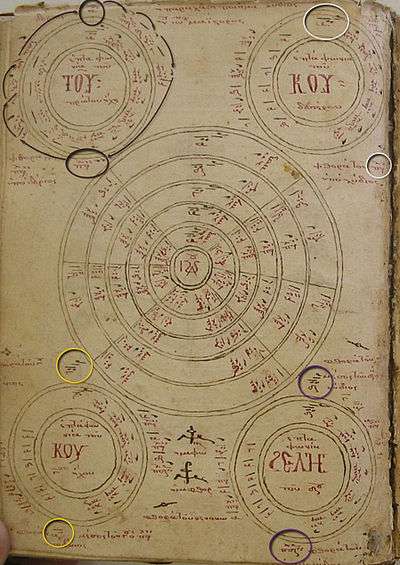

St. John Koukouzelis depicted on a 15th-century musical codex at the Great Lavra Monastery, Mount Athos, Greece. | |

| Born | Durazzo, Eastern Roman Empire |

| Residence | Mount Athos |

| Other names | Jan Kukuzeli |

| Education | Constantinople |

| Occupation | singer, composer |

| Known for | Reformer of Orthodox Church music |

John Koukouzelis or Jan Kukuzeli (Albanian: (Shën) Jan Kukuzeli; Bulgarian: Йоан Кукузел, Yoan Kukuzel; Greek: Ιωάννης Κουκουζέλης, Ioannis Koukouzelis; c. 1280 – c. 1360) was an Albanian-Bulgarian medieval Orthodox Christian composer, singer and reformer of Orthodox Church music.[1]

Early life

Koukouzelis was born in Durazzo, at the time part of the Angevin Kingdom of Albania[2] in the late 13th century to an Albanian father[3][4][5] and a Bulgarian mother.[6][7][8] He was orphaned in childhood.[9]

According to some sources he was born in Džerminci, near Debar, which is presently uninhabited.[10] Koukouzelis' last name is allegedly derived from the Greek word for broad beans (κουκιά, koukia) and a Slavic word for cabbage (зеле, zele).[11][12]

Most scholars, including David Marshall Lang, state that his mother was simply of Bulgarian origin,[11][12][13][14][15][16][17] while Robert Elsie generalizes her as being of Macedonian Slav descent.[18] However, according to Raymond Detrez, despite that his mother may have been a Bulgarian,[19] her Slavic origin is obscure.[20]

At a young age, he was noted and accepted into the school at the imperial court at Constantinople.[12]

His contribution as a master of psaltic art

Koukouzelis received his education at the Constantinople court vocal school and established himself as one of the leading authorities in his field during the time. A favourite of the Byzantine emperor and a principal choir chanter, he moved to Mount Athos and led a monastic way of life in the Great Lavra. Because of his singing abilities, he was called "Angel-voiced".[14]

Koukouzelis established a new melodious ("kalophonic") style of singing out of the sticherarion.[21] Some years after the fall of Constantinople Manuel Chrysaphes characterised the sticheron kalophonikon and the anagrammatismos as new genres of psaltic art which were once created by John Koukouzelis. Despite his innovations, Manuel assured that John Koukouzelis never contradicted the traditional method of the old sticherarion, not even in his anagrammatismoi.

| “ | ἀλλὰ μηδὲ τὸν δρόμον, ὦ οὗτος, τῆς μουσικῆς ἁπάσης τέχνης καὶ τὴν μεταχείρησιν ἁπλῆν τινα ωομίσῃς εἶναι καὶ μονοειδῆ, ὥστε τὸν ποιήσαντα στιχηρὸν καλοφωνικὸν μετὰ θέσεων ἁρμοδίων, μὴ μέντοι γε καὶ ὁδὸν τηρήσαντα στιχηροῦ, καλῶς ἡγεῖσθαι τοῦτον πεποιηκέναι καὶ τὸ ποιηθὲν ὑπ’ αὐτοῦ καλὸν ἁπλῶς εἶναι καὶ μώμου παντὸς ἀνεπίδεκτον· ἐπεὶ εἰ καὶ μεταχείρησιν στιχηροῦ τὸ ὑπ’ αὐτοῦ γινόμενον οὐκ ἕχει, τῷ ὄντι οὐκ ἔστιν ἀνεπίληπτον. μὴ τοίνυν νόμιζε ἁπλῆν εἶναι τὴν τῆς ψαλτικῆς μεταχείρησιν, ἀλλὰ ποικίλην τε καὶ πολυχιδῆ καὶ πολὺ τι διαφέρειν ἀλλήλων. [...] ἔνθεντοι κἄν τοῖς καλοφωνικοῖς στιχηροῖς οἱ τούτων ποιηταὶ τῶν κατὰ τὰ ἰδιόμελα μελῶν οὐκ ἀπολείπονται, ἀλλὰ κατ’ ἴχνος ἀκριβῶς ἀκολουθοῦσιν αὐτοῖς καὶ αὐτοῖς μέμνηνται. ὡς γοῦν ἐν μέλεσι διὰ μαρτυρίας καὶ τῶν ἐκεῖσε καιμένων μελῶν ἔνια παραλαμβάνουσον ἀπαραλλάκτως, καθάπερ δὴ καὶ ἐν τῷ στιχηραρίῳ ἔκκειντο, καὶ τὸν ἐκεῖσε πάντες δρόμον παρ’ ὅλον τὸ ποίημα τρέχουσιν ἀμετατρέπτει, καὶ τῷ πρωτέρῳ τε τῶν τοιητῶν ἀεὶ ὁ δεύτερος ἕπεται καὶ τοῦτο ὁ μετ’ αὐτόν, καὶ πάντες ἁπλῶς ἔχονται τῆς τέχνης ὁδοῦ. [...]

Ὁ γὰρ χαριτώνυμος μαΐστωρ, ὁ Κουκουζέλης, ἐν τοῖς ἀναγραμματισμοῖς αὐτοῦ τῶν παλαιῶν οὐκ ἐξισταται στιχηρῶν, ἀλλὰ κατ’ ἴχνος τούτοις ακολουθαῖ, δυνάμενος ἄν πάντως καὶ αὐτός, ὡς οἱ νῦν, καὶ πολὺ μᾶλλον εἴπερ οὗτοι, μέλη μόνα ποιεῖν ἴδια, μηδέν τι κοινωνοῦντα τοῖς πρωτοτύποις αὐτῶν στιχηροῖς. ἀλλ’ εἰ οὕτως ἐποίει, οὔτε καλῶς ἂν ἐποίει, οὔτε ἐπιστήμης προσηκόντως ἐπαΐειν ἐδοκει. διὸ καὶ κατ’ ἀκρίβειαν τοῦ τῶν παλαιῶν στιχηρῶν ἔχεται δρόμου καὶ αὐτῶν οὐ πάνυ τοι ἐξίσταται, τοῖς τῆς ἐπιστήμης νόμοις πειθόμενος.[22] |

” |

But, O my friend, do not think that the manner of the whole musical art and its practice is so simple and uniform that the composer of a kalophonic sticheron [the soloistic sticheron kalophonikon (στιχηρὸν καλοφωνικὸν)] with appropriate theseis who does not adhere to the manner of old sticheron [the conventional simple way to perform a sticheron with two choirs] can think that he has done well and that which he has written quite good and free from every condemnation – since, if what he has composed does not include the method of the old sticheron, it is not correct. Do not think therefore, that the performance of chant is simple, but rather that it is complex and of many forms. [...] Thus even in the kalophonic stichera the composers of these do not depart from their original melodies [τὰ ἰδιόμελα] but follow them accurately, step by step, and retain them. Therefore, they take over some melodies unchanged from tradition and from the music thus preserved (as it is recorded in the old Sticherarion [the simple sticherarion according to the redaction and its variants since the 14th century]), and they all follow the path unaltered throughout the entire composition. The second composer always follows his predecessor and his successor follows him and, to put it simply, everyone retains the technique of the art. [...]

Ioannes Koukouzeles, the maistor, does not alter the stichera in his anagrammatismoi [the more deliberate compositions of a sticheron kalophonikon about the final section of a certain sticheron which usually also changed its text and reworked its melodic structure], but follows them step by step, although, like composers now, he was entirely able (indeed he was much more able) to create his own original chants which had nothing in common with their prototype stichera [the simple sticheron as it was traditionally notated in the books of the sticherarion]. But, had he acted thus, he would neither acted correctly nor would he have thought that he had interpreted the science of composition befittingly. Therefore, he follows the path of the old stichera precisely and does not alter them at all, obeying the rules of the science.

The school of John Glykys and his followers like John and Xenos Korones created the "Late Byzantine" system of round notation. But the use of just one notation system could seduce to the conclusion, that every chant genre has to be performed in the same way. Instead a huge number of different methods had to be observed, which were part of an oral tradition, sometimes even of a particular one which depended on a certain local school. However, the notation itself is sometimes not regarded as one system of its own, since it simply continued an already existing synthesis of many different notations (like the one of the asmatikon) within the notation developed in the monastic books of the sticherarion and the heirmologion. John Koukouzelis is also regarded as the creator of a new chant book which replaced the former books of the cathedral rite, the book of the choir (asmatikon), and the book of the lampadarios or monophonaris who sometimes replaced the left choir. The latter book was called "psaltikon" or "kontakarion", while the new book which combined the content of the older books, was called "order of services" (τάξις τῶν ἀλολουθίων) and these manuscripts are conventionally ascribed to John Koukouzelis.[23] The Constantinopolitan redaction of the sticherarion and the heirmologion during the fourteenth century were often ascribed to John as well, but it was obviously neither the redaction of just one scribe, nor did the new kalophonic method intend any changes which contradicted the traditional ways. John Koukouzelis was obviously just one among a group of very talented musicians and reformers. Nevertheless, his legendary reputation caused that he is often identified with the reform itself. This identification is a common phenomenon in many Oriental and Andalusian traditions whose orally based transmission had never been completely abandoned.

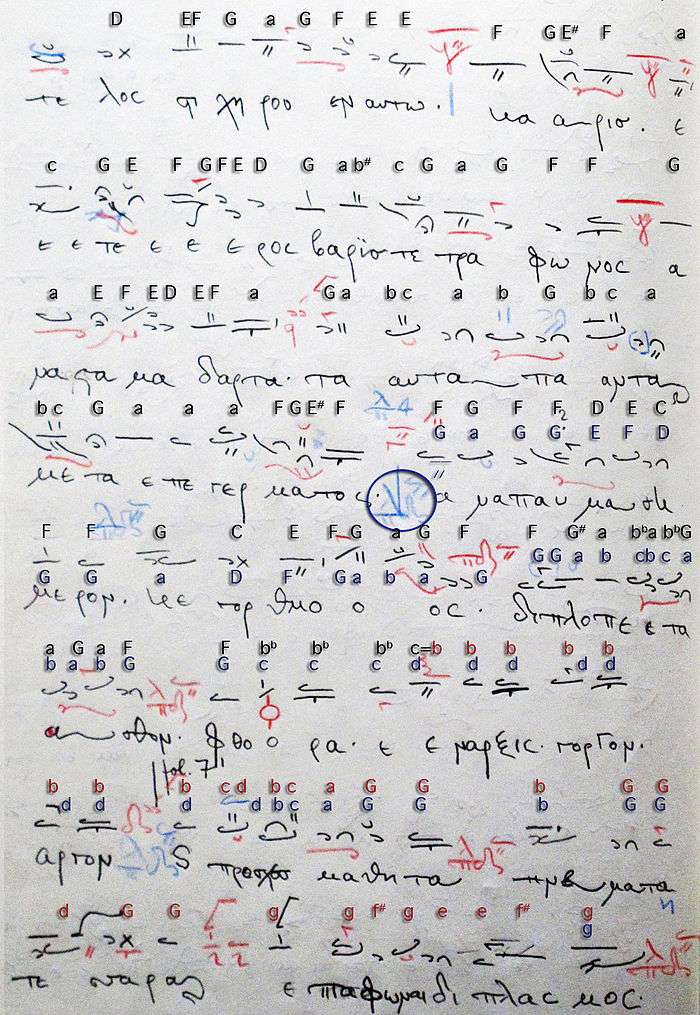

The kalophonic method of John Koukouzelis can be studied by means of a vocal exercise "Mega Ison" which offered 60 designations of vocal signs. Also this didactic chant was a redaction of a similar one by John Glykys which probably developed from a simple list of notation signs as an essential part of a treatise genre called Papadike. The "exercise" (mathema) Mega Ison instead is a complex composition whose melos changes between all the echoi of the Papadic octoechos.

Reception history of Koukouzelian compositions

In general it is useful to make a distinction between compositions which can be verified as the compositions by John Koukouzelis, and those which are simply based on the method which he taught (as a stylistic category based on the kalophonic melos as exemplified by Mega Ison). Even concerning famous compositions, their authorship is often a subject of scholarly debates whose concern is not always the talent of one individual composer—like the Polyeleoi of the Bulgarian Woman dedicated to his mother that, according to some researchers, contains elements of traditional Bulgarian mourning songs.[7][14] Greek editions of the same Polyeleos are different and especially the authorship of the Kratema used in the Bulgarian edition has been a controversial issue.[24] Concerning stichera kalophonika, there are numerous compositions made up in his name, but his authorship must be regarded as a certain school which had a lot of followers and imitators.

Modern print editions of chant books have only a very few compositions (different melismatic echos varys realisations of Ἄνωθεν οἱ προφήται, several Polyeleos compositions, the cherubikon palatinon, the Mega Ison, the Anoixantaria) which are almost never sung, except the short Sunday koinonikon, for the very practical reason that most of John Koukouzelis' compositions, at least based on the exegetic transcriptions by Chourmouzios Chartophylakos (GR-An Ms. ΜΠΤ 703), are simply too long.[25]

Sainthood and legacy

Koukouzelis is regarded as the most influential figure in the music of his period. He was later recognized as a saint by the Eastern Orthodox Church, his feast day being on 1 October.[26] He is known as Saint John Koukouzelis (Greek: Άγιος Ιωάννης Κουκουζέλης, Hagios Ioannis Koukouzelis, Bulgarian: Свети Йоан Кукузел, Sveti Yoan Kukuzel, Albanian: Shën Jan Kukuzeli, Macedonian: Свети Јован Кукузел, Serbian: Свети Јован Кукузељ).

A musical school in his native Durrës bears his name. Kukuzel Cove in Livingston Island in the South Shetland Islands, Antarctica is named after Koukouzelis, using the Slavic form of his name.

References

- ↑ Ostrogorski, K. (2004). The art of Medieval Europe. Rome. p. 121.

- ↑ Randel, Don Michael (1999). Don Michael Randel, ed. The Harvard concise dictionary of music and musicians (2nd ed.). Harvard University Press. p. 355. ISBN 978-0-674-00084-1.

- ↑ Helen C. Evans, William D. Wixom (2013). The Glory of Byzantium: Art and Culture of the Middle Byzantine Era, A. D. 843-1261. p. 600.

There is no doubt his father was an Albanian...his mother, a Bulgarian.

- ↑ Mark Mazower, "The Balkans: A Short History", pg. 76

- ↑ Balkan Ghosts: A Journey Through History

- ↑ Kazhdan, Alexander, ed. (1991), "Koukouzeles, John", Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium, Oxford University Press, p. 1155, ISBN 978-0-19-504652-6,

There is evidence... that his mother was Bulgarian.

- 1 2 "725 години от рождението на Йоан Кукузел" (in Bulgarian). Ruse Library website. Retrieved 2007-05-06.

- ↑ Maguire, Robert A.; Alan Timberlake (1998). American contributions to the Twelfth International Congress of Slavists. Slavica. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-89357-274-7.

For instance, the famous reformer of Byzantine music, loan Kukuzel (ca. 1302-ca. 1360), not only used his musical composition "Polieleos of a Bulgarian Woman" melodic elements from his mother's laments...

- ↑ "Venerable John (Koukouzelis)", Orthodox Church in America

- ↑ Janko Petrovski; Aleksandar Dautovski; Angelikija Anakijeva (2004). Undying creativity: a pictorial journey through Macedonia. MacedoniaDirect. pp. 77–. ISBN 978-9989-2343-0-9.

- 1 2 "Св. Йоан Кукузел — тропар, кондак и житие" (in Bulgarian). Pravoslavieto.com. Retrieved 2007-05-06.

- 1 2 3 "St. John Kukuzelis". Orthodox America. Retrieved 2007-05-06.

- ↑ Dujcev, Ivan. Medioevo bizantino-slavo, vol. II. Ed. di Storia e Letteratura. p. 222.

- 1 2 3 Бакалов, Георги; Милен Куманов (2003). "Йоан Кукузел (ок. 1280-1360)". Електронно издание "История на България" (in Bulgarian). София: Труд, Сирма. ISBN 954528613X.

- ↑ Lang, David Marshall (1976). The Bulgarians: from pagan times to the Ottoman conquest. Westview Press. p. 145. ISBN 978-0-89158-530-5.

John Kukuzel, the eminent Bulgarian/born reformer of Byzantine music.

- ↑ Aleksandr Mikhaĭlovich Prokhorov (1982). Great Soviet encyclopedia. 13. Macmillan. p. 551.

- ↑ Nicholas P. Brill (1980). History of Russian Church Music, 988-1917. Brill. pp. 11–12.

- ↑ Robert Elsie. "The Dictionary of Albanian Religion, Mythology and Folk Culture". p. 138. Retrieved 25 October 2015.

- ↑ Historical Dictionary of Bulgaria, Raymond Detrez, Rowman & Littlefield, 2014, ISBN 1442241802, p. 531.

- ↑ The A to Z of Bulgaria, Raymond Detrez, Scarecrow press, ISBN 0810872021, p. 487.

- ↑ See as an example Maria Alexandru's study (2011) of John Koukouzelis' composition of a sticheron kalophonikon which he created over a part (ποὺς) of a traditional sticheron for Saint Demetrios.

- ↑ See the edition and translation by Dimitri Conomos (1985, 40–45).

- ↑ See the Akolouthiai written in Thessaloniki (ca. 1400) which contained most of the chant performed during the three ceremonies of the new mixed cathedral rite: the Hesperinos, the Orthros, and the Divine Liturgies, except of the kontakia. The break with the former cathedral rite was less meant as an innovative act of certain composers in Constantinople, it was due to the historic fact that this tradition was definitely lost since the long exile of the court and the patriarchate during the thirteenth century. Hence, even the kontakia did not come out of use, but its repertoire became very limited and the few known kontakia were performed in a rather melismatic style which provoked further simplifications.

- ↑ Sarafov's edition (1912, 201–203) has a teretismos which ends a fifth too high for the Polyeleos composition, his edition of compositions ascribed to John Koukouzelis is regarded as authoritative by Bulgarian chanters until today (listen to the interpretation of the Bulgarian Byzantine choir under direction of Dimiter Dimitrov).

- ↑ Some collections of stichera kalophonika made alone of the Menaion cycle—they were usually called "exercise books" (mathemataria)—have a volume of 1900 pages. In fact, even the traditional way to sing the sticheraric melos had been already so expanded, that the modern editions must all regarded as different efforts to abridge the traditional melos.

- ↑ Great Synaxaristes: (in Greek) Ὁ Ὅσιος Ἰωάννης ὁ ψάλτης ὁ καλούμενος Κουκουζέλης. 1 Οκτωβρίου. ΜΕΓΑΣ ΣΥΝΑΞΑΡΙΣΤΗΣ.

Manuscripts

- Koukouzeles, Ioannes; Korones, Xenos; Kladas, Ioannes (1400). "Vienna, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Cod. theol. gr. 185". Βιβλίον σὺν Θεῷ ἁγίῳ περιέχον τὴν ἄπασαν ἀκολουθίαν τῆς ἐκκλησιαστικῆς τάξεως συνταχθὲν παρὰ τοῦ μαΐστορος κυροῦ Ἰωάννου τοῦ Κουκουζέλη. Thessaloniki.

- Germanos Hieromonachos; Panagiotes the New Chrysaphes; Petros Bereketes; Anastasios Skete; Balasios Iereos; Petros Peloponnesios; Petros Byzantios. "Athens, Ιστορικό και Παλαιογραφικό Αρχείο (ΙΠΑ), MIET, Ms. Pezarou 15". Anthologiai of Psaltic Art (late 18th century). Athens: Μορφωτικό Ίδρυμα Εθνικής Τράπεζας. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 29 September 2012.

- Koukouzeles, Ioannes (1819). Chourmouzios the Archivist (ed.), ed. "Athens, National Library of Greece (EBE), Metochion of Panagios Taphos (ΜΠΤ) 703". Manuscript with Chourmouzios' transcriptions of 14th-century composers (Ioannes Glykys, Ioannes Koukouzeles, Xenos Korones, Ioannes Kladas etc.) according to the New Method. Istanbul.

Print editions

- Petĕr V. Sarafov, ed. (1912). "Biografiya na Sv. Ioan Kukuzel, Iz carigradskaya prĕvod (Aniksantari, Golĕmoto Iso, Poleyleyat na Bĕlgarkata, Heruvimska pĕsn, Pričastno, Svyše prorocy)". Rĕkovodstvo za praktičeskoto i teoretičesko izučvane na Vostočnata cĕrkovna muzika, Parachodni uroci, Voskresnik i Antologiya (Polielei, Božestvena služba ot Ioana Zlatoousta, Božestvena služba na Vasilij Velikij, Prazdnični pričastni za prĕz cĕlata godina, Sladkoglasni Irmosi). Sofia: Peter Gluškov. pp. 131–216.

- Chourmouzios the Archivist (1896). Kyriazides, Agathangelos, ed. "Τὸ Μέγα Ἴσον τῆς Παπαδικῆς μελισθὲν παρὰ Ἰωάννου Μαΐστορος τοῦ Κουκκουζέλη, Χερουβικὸν παλατινὸν, Κοινωνικὸν". Ἐν Ἄνθος τῆς καθ' ἡμᾶς Ἐκκλησιαστικῆς Μουσικῆς περιέχον τὴν Ἀκολουθίαν τοῦ Ἐσπερίνου, τοῦ Ὅρθρου καὶ τῆς Λειτουργίας μετὰ καλλοφωνικῶν Εἴρμων μελοποιηθὲν παρὰ διάφορων ἀρχαιῶν καὶ νεωτερῶν Μουσικόδιδασκαλων. Istanbul: Alexandros Nomismatides: 127–144;278–287;350–353.

Papadikai and their editions

- "Hiera Mone of Timios Prodromos (Skete) Veroias, Ms. 1". Papadike (1796). Retrieved 6 February 2013.

- Alexandrescu, Ozana (2011). "Tipuri de gramatici în manuscrise muzicale de tradiţie bizantină". Studii şi cercetări de istoria artei. Teatru, muzică, cinematografie. Serie novă. 49-50: 21–55.

- Alexandru, Maria (1996). "Koukouzeles' Mega Ison: Ansätze einer kritischen Edition" (PDF). Cahiers de l'Institut du Moyen-Âge grec et latin. 66: 3–23.

- Conomos, Dimitri, ed. (1985), The Treatise of Manuel Chrysaphes, the Lampadarios: [Περὶ τῶν ἐνθεωρουμένων τῇ ψαλτικῇ τέχνῃ καὶ ὧν φρουνοῦσι κακῶς τινες περὶ αὐτῶν] On the Theory of the Art of Chanting and on Certain Erroneous Views that some hold about it (Mount Athos, Iviron Monastery MS 1120, July 1458), Monumenta Musicae Byzantinae - Corpus Scriptorum de Re Musica, 2, Vienna: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, ISBN 978-3-7001-0732-3.

- Fleischer, Oskar, ed. (1904), "Die Papadike von Messina", Die spätgriechische Tonschrift, Neumen-Studien, 3, Berlin: Georg Reimer, pp. 15–50; fig. B3-B24 [Papadike of the Codex Chrysander], retrieved 11 April 2012.

- Hannick, Christian; Wolfram, Gerda, eds. (1985), Gabriel Hieromonachus: [Περὶ τῶν ἐν τῇ ψαλτικῇ σημαδίων καὶ τῆς τούτων ἐτυμολογίας] Abhandlung über den Kirchengesang, Monumenta Musicae Byzantinae - Corpus Scriptorum de Re Musica, 1, Vienna: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, ISBN 3-7001-0729-3.

- Tardo, Lorenzo (1938), "Papadiche", L'antica melurgia bizantina, Grottaferrata: Scuola Tipografica Italo Orientale "S. Nilo", pp. 151–163.

Studies

- Alexandru, Maria (2011). "Byzantine Kalophonia, illustrated by St. John Koukouzeles’ piece Φρούρηζον πανένδοξε in Honour of St. Demetrios from Thessaloniki. Issues of Notation and Analysis". Studii şi cercetări de istoria artei. Teatru, muzică, cinematografie. Serie novă. 49-50: 57–105.

- Angelopoulos, Lykourgos (1997). "The "Exegesis" of Chourmouzios Hartofylax on Certain Compositions by Ioannis Koukouzelis". In Christian Troelsgård (ed.). Byzantine Chant – Tradition and Reform: Acts of a Meeting Held at the Danish Institute at Athens, 1993. Monographs of the Danish Institute at Athens. Århus: Aarhus University Press. pp. 109–122. ISBN 8772887338.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to John Koukouzeles. |

- Koukouzeles, Ioannes (13 December 2006). "John Koukouzeles' Teretismos composed in the mesos devteros sung by Ensemble Romeiko in Historic Costumes". National Library of Athens: Romeiko Ensemble.

- Koukouzelis, Ioannis. "Sticheron kalophonikon about Φρούρηζον (Protect, o most glorious) in echos plagios devteros". Greek Byzantine Choir - Lycourgos Angelopoulos.

- Kukuzel, Ioan. "Sunday Koinonikon Хвалите Господа с'небес in Glas 5". Sofia Priest Choir - Kiril Popov.

- Kukuzel, Ioan. "Polielei na Bĕlgarkata in Glas 5 (extracts)". Bulgarian Byzantine Choir - Dimitar Dimitrov.

- Koukouzelis, John. "Anoixantaria composed in echos plagios tetartos". Cappella Romana - Alexander Lingas.