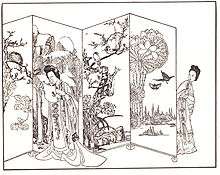

Yingying's Biography

The Biography of Ying-ying (traditional Chinese: 鶯鶯傳; simplified Chinese: 莺莺传; pinyin: Yīngyīng zhuàn; Wade–Giles: Ying-ying chuan), also translated as the Story of Yingying, by Yuan Zhen, is Tang dynasty chuanqi story.[1] It tells the story of a relationship conflicted between love and duty between a 16-year-old girl and a 21-year-old student. It is considered to be one of the first works of fiction in Chinese literature.

Role in history of Chinese literature

Yuan Zhen pioneered psychological exploration and possibilities of plot development. His tale mixed narration, poetry and letters from one character to another to demonstrate emotion rather than describe it, making it in one sense an epistolary novel. The work was also innovative because its characters, in the terms suggested by E.M. Forster, are “round” rather than “flat,” that is, unlike the characters in the earlier zhiguai or zhiren tales, are not built around a single idea or quality, but have the power to surprise readers. Recent critic Gu Mingdong suggests that with this tale, Chinese fiction “came of age,” and the story provided themes for later plays, stories, and novels.[2]

Yingying's Biography was one of three Tang Dynasty works particularly influential in the development of the caizi-jiaren (scholar and beauty story).[1]

Among other works which it inspired was the Story of the Western Wing [3]

Plot

The young man, known only as "the student Zhang" was living in a rented dwelling in a Buddhist compound in the countryside some distance from a small city when a recently widowed woman, her daughter and son, and an entourage befitting their wealth moved into another rented dwelling in that compound. The father of the family had died while stationed in some remote part of China, so the widow Cui (pronounced "tswei") was returning the family to Chang-an. They paused in their journey to recuperate from their long trek. Troops in the nearby city mutinied, so the student Zhang used his friendly connections with influential men in that city to get a guard posted over the compound. The widow Cui and her group were made much more secure as a result of the student Zhang's pulling of strings. She gave a banquet to express her gratitude for Zhang's actions.

The widow Cui instructed her daughter to attend the banquet and to say "thank you" to the student Zhang. However, the daughter only appeared because she was under duress, and behaved in a most petulant and churlish manner. Nevertheless, she appeared gloriously beautiful to Zhang despite her deliberately unkempt state. He had hitherto experienced no intimacy with anyone, and his cohorts had teased him about his lack of experience. There is no indication whatsoever that he had loving parents, siblings, or anyone in his life who was more to him than a mere acquaintance. He was immediately infatuated with this young woman who was so different from the young women who entertained his cohorts in the capital.

Zhang could not properly contact Cui Ying-ying (T: 崔鶯鶯, S: 崔莺莺, P: Cuī Yīngyīng, W: Ts'ui Ying-ying) directly. He arranged an indirect conduit through which he sent two "vernal" poems that the author of the story indicates would have conveyed no indecent propositions. Ying-ying responded with a poem that indicated romantic interest in "my lover," and invites him to come to her apartment after midnight. The student Zhang thought that "his salvation was at hand," i.e., that he would at last find an end to the long dearth of affection in his life. However, when he kept the appointment Ying-ying called him a virtual rapist. He was totally crushed. Several nights later, Ying-ying came to his apartment without prior arrangement and initiated intercourse with him. She said not a single word to him from the time she entered his apartment to the time she left at dawn the next day. Before long they had established a pattern in which Zhang would sneak into her dwelling each night, and sneak back out again the following dawn. Despite her daughter entertaining a virile man every night, the widow Cui did not intervene. When her daughter asked for her reaction she said, essentially, that her daughter had gotten herself into the current situation and should get herself out of it in any way she might choose.

After some months of the functional equivalent of young married life, the student Zhang had to go to the capital to take the yearly civil service examination that would determine whether he could get a good job in the government. Ying-ying felt that Zhang was abandoning her. She blamed him for attending to education and job seeking rather than staying with her. Zhang did not pass the examination and returned to the Buddhist compound. Ying-ying might have used this juncture to renegotiate their relationship. Instead, everything continued as before. Every time Zhang did anything to try to get to know her better, she rebuffed him. When the time of the next examinations came, Zhang again prepared to leave for the capital. Ying-ying was once more convinced that he was abandoning her. She eventually became very emotional about her "abandonment." Zhang left anyway.

When he arrived in the capital, he wrote to Ying-ying and attempted to set out his true feelings for her. She responded with a letter that implied that Zhang had been untrue to her, was interested only in his own future as an official, etc. Zhang did not react to this letter by feeling guilty. Instead, he decided that the relationship was bad for him. He may also have realized that the relationship was bad for Ying-ying. The story is not clear at this point and only says that Zhang decided to end things, and that he made certain rationalizations to his cohorts who thought he should let things go on as before.

After some time passed, the widow Cui managed to arrange a reasonably good marriage for Ying-ying. Zhang, too, found a wife. When his official duties took him near to Ying-ying's new home, he attempted to visit her. She refused to see him, but she sent him a poem that indicated that she was thoroughly miserable, and that this sorrow state of affairs was all Zhang's fault. He responded with a poem of his own, saying that the past and all the decisions each had made were all beyond recall and that she should direct her energies toward making a good relationship with her husband.

Translations

- James Hightower, "The Story of Yingying," in Minford, John and Joseph S. M. Lau, eds. (2000). Classical Chinese Literature: An Anthology of Translations I. From Antiquity to the Tang Dynasty. New York; Hong Kong: Columbia University Press; The Chinese University Press. ISBN 0231096763. pp. 1047–1057.

- Patrick Moran, "The Biography of Ying-ying — Enthrallment to Beauty, Destruction by Desire (includes Chinese text), .]

- Owen, Stephen, "Yingying's Story," in Stephen Owen, ed. An Anthology of Chinese Literature: Beginnings to 1911. New York: W. W. Norton, 1997. p. 540-549 (Archive (Archive).

- Arthur Waley, “The Story of Ts’ui Yingying,” More Translations From Chinese (1919) Sacred Texts (also in the Anthology of Chinese Literature by Cyril Birch, vol. I. (ISBN 0-8021-5038-1);[4]

- "The Story of Cui Yingying" (Archive" (Archive), Indiana University.

References and further reading

- Hightower, James (1973). "Yuan Chen and the 'Story of Yingying'". Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies. 33: 90–123.

- Luo, Manling, "The Seduction Of Authenticity: 'The Story Of Yingying'." (Archive." (Archive). Nan Nü 7.1. Brill, Leiden, 2005. p. 40-70.

- Song, Geng (2004). The Fragile Scholar: Power and Masculinity in Chinese Culture. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press. ISBN 9622096204.

- Yu, Pauline. "The Story of Yingying" (Archive" (Archive). In: Yu, Pauline, Peter Bol, Stephen Owen, and Willard Peterson (editors). Ways with Words: Writing about Reading Texts from Early China (Volume 24 of Studies on China). University of California Press, 2000. ISBN 0520224663, 9780520224667. p. 182-185.

Notes

- 1 2 Song (2004), p. 23-21.

- ↑ Gu, Mingdong Chinese Theories of Fiction (Albany: SUNY Press), pp. 81- 82

- ↑ Indiana Companion to Traditional Chinese Literature p. 408

- ↑ Nienhauser, William H. "Introduction." In: Nienhauser, William H. (editor). Tang Dynasty Tales: A Guided Reader. World Scientific, 2010. ISBN 9814287288, 9789814287289. p. xv.

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Lament for Ying-ying Chinese Forums.