Yelloweye rockfish

| Yelloweye rockfish | |

|---|---|

| |

| Typical adult | |

| |

| Typical young | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Scorpaeniformes |

| Family: | Sebastidae |

| Genus: | Sebastes |

| Species: | S. ruberrimus |

| Binomial name | |

| Sebastes ruberrimus (Cramer, 1895) | |

The yelloweye rockfish (Sebastes ruberrimus) is a rockfish of the genus Sebastes, and one of the biggest members of the genus. Its name derives from its coloration. It is also locally known as "red snapper",[1][2] not to be confused with the warm-water species Lutjanus campechanus that formally carries the name red snapper. The yelloweye is one of the world's longest-lived fish species, and is cited to live to a maximum of 114 to 120 years of age. As they grow older, they change in color, from reddish in youth, to bright orange in adulthood, to pale yellow in old age. Yelloweye live in rocky areas and feed on small fish and other rockfish. They reside in the East Pacific and range from Baja California to Dutch harbor in Alaska.

Yelloweye rockfish are prized for their meat, and were declared overfished in 2002, at which time a survey determined that their population, which had been in decline since the 1980s, was just 7–13% of numbers before commercial fishing of the species began. Because of the slow reproductive age of the species, recovery of the species is difficult, and liable to last decades, even with the harshest restrictions; Washington state, for example, maintains a quota of under 1000 individuals per year. It is currently under consideration for listing under Threatened or Endangered status.

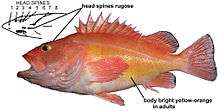

Characteristics

The yelloweye rockfish is colored red on its back, orange to yellow on the sides, and black on the fin tips. Its young are typically under 28 cm (11 in) in length, and differ from the adults in that they have two reddish-white stripes along their belly,[3] and are often red. Because of the distinct difference in coloration between juveniles and adults, they were considered separate species for a long time.[4] Its head spines are exceptionally strong. They grow to a maximum length of 36 in (0.9 m) and are typically found in the 28-to-215-fathom (51-to-393 m) range, although specimen have been reported up to a maximum depth of 260 fathoms (475 m).[3]

Yelloweye rockfish live to be extremely old, even for their unusually long-lived genus. They average 114[1] to 120[2] years of age; the oldest ones reach as much as 147 years. They fade from bright orange to a paler yellow as they grow in age. They are exceptionally slow developing as well, not reaching maturity until they are around 20 years of age.[1]

Diet

Larval yelloweye feed on diatoms, dinoflagellates, crustaceans, tintinnids, and cladocerans, and juveniles consume copepods and euphausiids of all life stages. Adults eat demersal invertebrates and small fishes, including other species of rockfish.[4]

Habitat

The yelloweye rockfish has been recorded all along the East Pacific, from Umnak Island and Prince William Sound, Alaska, to Ensenada, Baja California.[5] They are typically found in deeper, rocky-bottomed areas; in fact, they often spend their entire lifetime on a single rock pile.[2]

Value to fishing

Due to their large size and fillet quality, yelloweye rockfish are a highly prized species in both commercial and recreational fisheries. Historically, yelloweye are taken in by trawl, line, and sports gear. Fishing of the species using trawls was restricted following a 2000 resolution to keep trawlers out of their primary habitats.[6]

Yelloweye brought to the surface by fishing boats tend to die of decompression barotrauma and temperature shock. According to the Alaska Department of Fish and Game, the fish is liable to die if brought to the surface from a depth of over 10 fathoms (60 ft; 18 m).[6]

Recent federal research by John Hyde at National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's (NOAA's) Southwest Fisheries Science Center in San Diego indicates that, after a yelloweye is brought to the surface, devices which bring these fish back to 45 meters below the sea surface may allow the fish to recompress and survive, analogous to 'an ambulance ride home after an angler catches it.' The federal Pacific Fishery Management Council (PFMC) may begin considering proposals to compensate anglers for using these devices, as a means to restore fish stocks.[7]

Overfishing

A stock assessment of the species, which incorporated data gathered from northern California and Oregon, was done in 2001. The study concluded the fish's numbers are just 7% of what they would be without human intervention in northern California, and a slightly higher 13% in Oregon. The assessment also showed a 30-year decline in numbers. These numbers are far below the 25% threshold at which a fish is labeled "overfished." As a result, the yellowfish is separated from the assessment group of rockfish in general of which it was a part.[6]

Although efforts are being made to facilitate a recovery in numbers, a formal rebuilding of the species would take decades, as much as 100 years of recovery. This is associated with the fact that they do not reach sexual maturity until they are 10 to 20 years of age.[1][6] A total of 13.5 metric tons (29,800 lb) of yelloweye catch were allowed coastwide in 2002. This limit is set so that fisheries can potentially catch yelloweye if they are caught accidentally, but prevents the targeted fishing of the species. The Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, meanwhile, prohibited retention of yelloweye rockfish caught by recreational fisheries. The Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife has a daily limit of one yelloweye rockfish. Commercial retention of the rockfish is prohibited except for a small 300 lb (136 kg) limit, to allow yellowfish caught dead to be retained.[6] California's sportfishing regulations prohibit the take or possession of Yelloweye rockfish (also Cowcod and Bronzespotted and Canary Rockfish).[8]

As time passed, the restrictions on fishing became stricter; the 2009 Washington state quota is just 6,000 pounds (2.7 t), fewer than 1000 fish. State departments are prepared to close down anglers hunting halibut to protect the species if the situation becomes dire.[2]

{http://www.nmfs.noaa.gov/pr/species/fish/yelloweyerockfish.htm They are listed as EPA Threatened. />

References

- 1 2 3 4 "Orion Charters - Rock Fish". 10/06/06. Retrieved 26 November 2009. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - 1 2 3 4 "Protecting Washington’s Yelloweye Rockfish". Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife. 2009. Archived from the original on 30 March 2013. Retrieved 26 November 2009.

- 1 2 "Yelloweye rockfish". NOAA. Retrieved 26 November 2009.

- 1 2 "Yelloweye Rockfish (Sebastes ruberrimus)". NOAA Office of Protected Resources. Retrieved 26 November 2009.

- ↑ "Sebastes ruberrimus". Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife. Archived from the original on 4 November 2011. Retrieved 26 November 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Avoid Yelloweye Rockfish". June 4, 2002. Archived from the original on 2 February 2010. Retrieved 26 November 2009.

- ↑ Chen, Ingfei (June 13, 2011). "Putting Rockfish Back Where They Belong". Science. Retrieved November 6, 2012.

- ↑ https://www.wildlife.ca.gov/Fishing/Ocean/Regulations/Sport-Fishing

External links

- Milton S. Love, Mary Yoklavich, Lyman K. Thorsteinson, (2002), The Rockfishes of the Northeast Pacific, University of California Press, pp. 234–236

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2009). "Sebastes ruberrimus" in FishBase. August 2009 version.

- National Marine Fisheries Service canary rockfish webpage