Yaphank, New York

| Yaphank, New York | |

|---|---|

| Hamlet and census-designated place | |

|

The historic Swezey-Avey House on the southeast bank of Upper Yaphank Lake | |

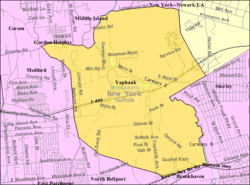

U.S. Census map | |

Yaphank Location within the state of New York | |

| Coordinates: 40°50′7″N 72°55′45″W / 40.83528°N 72.92917°WCoordinates: 40°50′7″N 72°55′45″W / 40.83528°N 72.92917°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | New York |

| County | Suffolk |

| Area | |

| • Total | 13.8 sq mi (35.7 km2) |

| • Land | 13.7 sq mi (35.4 km2) |

| • Water | 0.1 sq mi (0.3 km2) |

| Elevation | 43 ft (13 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 5,945 |

| • Density | 430/sq mi (170/km2) |

| Time zone | Eastern (EST) (UTC−05:00) |

| • Summer (DST) | EDT (UTC−04:00) |

| ZIP code | 11980 |

| Area code(s) | 631 |

| FIPS code | 36-83426[1] |

| GNIS feature ID | 0971807[2] |

| [3] | |

Yaphank (/ˈjæpeɪŋk/) is a hamlet and census-designated place (CDP) in Suffolk County, New York, United States. The population was 5,945 at the time of the 2010 census.[4]

Yaphank is located in the south part of the Town of Brookhaven. It is served by the Longwood Central School District, except for extreme southwestern Yaphank, which is served by the South Country Central School District.

History

Captain Robert Robinson came to Yaphank and built his Dutch Colonial house with the building dated at 1726. He was then granted permission to dam the Carmans River to build a mill across the street from his house. The construction of this mill in 1739 was considered the founding date of the Hamlet of Yaphank.[5]

In the mid 18th century, a man named John Homan built two mills along the Carmans River, which runs directly through the center of the town. These two mills inspired the first name for the town: Millville. The translator/author Mary Louise Booth was born in Millville in 1831. In 1846 a post office was opened in the town, but because there were thirteen other towns named "Millville" in New York state at the time, the town was renamed "Yaphank", from the local Native American word Yamphanke, meaning "bank of a river".

In 1843 the Long Island Rail Road built a railroad station in Yaphank (still named Millville at the time), and virtually overnight the small mill town became a major commercial center. By 1875, Yaphank had two grist mills, two lumber mills, two blacksmith shops, a printing office, an upholstery shop, a stagecoach line, two physicians, a shoe shop, two wheelwright shops, a meat market, a dressmaker and a general store.

Today, Yaphank is home to about half of those industries. The grist mills, blacksmith, physician, shoe shop, wheelwright shops, meat markets and the dressmakers are long gone, although the rail road station is still there, along with the general stores.

Today, Yaphank holds three delis, one pizza shop, a shooting supply company, a skeet range, a bank, and a house moving company.

Yaphank was the home of Camp Upton, which was used as a boot camp in 1917. In 1947, the U.S. Department of War transferred the Camp Upton site to the Atomic Energy Commission, and it now serves as the home of Brookhaven National Laboratory. Before the end of World War I, more than 30,000 men received their basic training there. Perhaps the most notable person to have trained at Camp Upton was the songwriter Irving Berlin. It was there he composed the musical comedy revue Yip Yip Yaphank, which had a brief run on Broadway.

A number of Suffolk County facilities are located in Yaphank, including Suffolk County Police Department headquarters, the county fire academy, and the Suffolk County Farm and Education Center, which offers a glimpse into the workings of an authentic 100+ year old farm and educational programs by Cornell Cooperative Extension.

A quarter horse racing facility named Parr Meadows operated in Yaphank in 1977. The racetrack reopened in 1986 for a single meet, then called Suffolk Meadows. In 1979, Parr Meadows served as the venue of a tenth anniversary reunion concert that featured many of the original performers from the Woodstock Festival.

Camp Siegfried and Siegfried Park

Yaphank was also home to Camp Siegfried, a summer camp which taught Nazi ideology.[6][7][8] It was owned by the German American Bund, an American Nazi organization devoted to promoting a favorable view of Nazi Germany, and operated by the German American Settlement League (GASL). Camp Siegfried was one of many such camps in the US in the 1930s, including Camp Hindenberg in Grafton, Wisconsin,[9] Camp Nordland in Andover, New Jersey,[10][11] and Deutschhorst Country Club in Sellersville, Pennsylvania.[12]

Camp Siegfried had a pool, archery competitions, hikes through the woods, a Youth Camp on the other side of Upper Lake, oom-pah bands and Oktoberfest celebrations; women in German peasant outfits greeted visitors at the gate. Weekend-morning Long Island Railroad trains called "Camp Siegfried Specials" ran from Penn Station in New York City to Yaphank for the convenience of the camp's guests, many of whom came out from the German-American Manhattan neighborhood of Yorkville to spend time at what appeared to be a family-oriented summer retreat.[13][14][15][16] In 1938, The New York Times reported that 40,000 people attended that year's annual German Day festivities.[17][18]

But Camp Siegfried also had Nazi and Hitler Youth flags displayed on the grounds, along with pictures of Adolf Hitler, and men were photographed there in Italian Fascist-style blackshirts, SA-style brownshirts, and Nazi military uniforms. According to a court case brought against the German American Settlement League in 1938 for failing to register with New York's Secretary of State – a violation of the Civil Rights Law of 1923, which was enacted to control the Ku Klux Klan – to become a member of the League one had to swear allegiance to Hitler and to the leaders of the German American Bund; the court found against the League.[19][14][15][20] During the trial, a witness was asked to demonstrate how those at the camp saluted the American flag. Under duress, he responded by giving the Nazi salute. When asked if this was "the American salute", the witness responded "It will be."[16]

According to The Washington Post, the purpose of Camp Siegfried was to "Raise the future leaders of America – and make sure they were steeped in Nazi ideals." These future Aryan leaders were not only forced to physically build the camp's infrastructure – so as to avoid hiring union labor, when the unions were, the camp's leaders thought, full of Jews – but were also coerced into having sex with each other in order to breed a new generation of perfect Aryan children.[13][20][15][14][17]

The German American Bund severed its connection with the German American Settlement League in 1940, and the League took over the Camp with the announcement that henceforth it would be "non-political."[21] Neverthesless, the camp was seized and shut down by the US government when Germany declared war on the United States. It had been protected by the First Amendment until that time, when it became illegal for American citizens to swear allegiance to Germany.

Camp Siegfried was transformed into "German Gardens", a planned community which had been approved by the Town of Brookhaven in 1936. Located along Upper Lake, part of German Gardens – where streets named after Hitler, Joseph Goebbels and Hermann Göring were not changed until 1941[22] – was later absorbed by Yaphank, while the remainder became Siegfried Park, a 40-acre private community of small bungalows and suburban-type ranch houses with well-kept lawns, where the land under the houses was owned by the German American Settlement League, and no one could buy a house without being approved by the League. Technically a co-op, the League's by-laws included a restrictive covenant that all home-buyers had to be mostly "of German extraction." This was struck down by a Federal judge in 2016 as the result of a lawsuit, and the community's bylaws were rewritten to require it to comply with all fair housing laws, at the federal, state and local levels, but the discriminatory practices continued despite this, with the League making it difficult for home-owners to sell their houses. In May 2017, New York state prosecutors announced that they had reached a settlement with the League to end any discriminatory housing policies and practices. According to the state's Attorney General, Eric Schneiderman, the agreement "will once and for all put an end to the GASL's discrimination."[13][20][14][17]

Geography

According to the United States Census Bureau, the CDP has a total area of 13.8 square miles (35.7 km2), of which 13.7 square miles (35.4 km2) is land and 0.12 square miles (0.3 km2), or 0.89%, is water.[4]

Demographics of the CDP

As of the census[1] of 2000, there were 5,025 people, 1,566 households, and 1,130 families residing in the CDP. The population density was 359.5 per square mile (138.8/km²). There were 1,650 housing units at an average density of 118.0/sq mi (45.6/km²). The racial makeup of the CDP was 85.11% White, 11.22% African American, 0.24% Native American, 1.03% Asian, 0.04% Pacific Islander, 0.94% from other races, and 1.41% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 7.34% of the population.

There were 1,566 households out of which 33.5% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 55.5% were married couples living together, 11.9% had a female householder with no husband present, and 27.8% were non-families. 21.9% of all households were made up of individuals and 6.8% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.69 and the average family size was 3.14.

In the CDP, the population was spread out with 21.9% under the age of 18, 8.0% from 18 to 24, 34.6% from 25 to 44, 24.0% from 45 to 64, and 11.6% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 37 years. For every 100 females there were 115.3 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 118.1 males.

The median income for a household in the CDP was $70,534, and the median income for a family was $72,348. Males had a median income of $48,807 versus $35,406 for females. The per capita income for the CDP was $25,020. About 3.3% of families and 3.8% of the population were below the poverty line, including 4.8% of those under age 18 and 4.7% of those age 65 or over.

See also

- Brookhaven Rail Terminal

- Robert Hawkins Homestead

- Homan-Gerard House and Mills

- St. Andrew's Episcopal Church (Yaphank, New York)

- Suffolk County Almshouse Barn

References

- 1 2 "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ↑ "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. 2007-10-25. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ↑ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. 2011-02-12. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- 1 2 "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (G001): Yaphank CDP, New York". U.S. Census Bureau, American Factfinder. Retrieved 2013-01-10.

- ↑ "An Old House – An Unusual House Guest" Yaphank Historical Society

- ↑ Shaffer, Ryan (Spring 2010). "Long Island Nazis: A Local Synthesis of Transnational Politics". Long Island History Journal. Retrieved 2012-02-05.

- ↑ Neuss, Gustave (November 2002). "The German American Bund". Longwood's Journey. Retrieved 2012-02-05.

- ↑ Miller, Marvin D (1983). Wunderlich's Salute: The Interrelationship of the German-American Bund, Camp Siegfried, Yaphank, Long Island, and the Young Siegfrieds and Their Relationship with American and Nazi Institutions. Malamud Rose Pubns. p. 336. ISBN 978-0-9610466-0-6.

- ↑ Van Ells, Mark D. (2007). "Americans for Hitler". America in World War 2. Retrieved 2012-02-05.

- ↑ Staff (1938). "American Nazis in the 1930s". Click Magazine. Retrieved 2012-02-05.

- ↑ Grover, Warren (2003). Nazis in Newark. Transaction Publishers. p. 292. ISBN 978-0-7658-0516-4.

- ↑ "German-American Bund". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2012-02-05.

- 1 2 3 Wootson, Cleve R. Jr. (May 19, 2017) "'Hitler Street' and swastika landscaping: A New York enclave's hidden Nazi past", The Washington Post

- 1 2 3 4 Casey, Nicholas (October 19, 2015) "Nazi Past of Long Island Hamlet Persists in a Rule for Home Buyers" The New York Times

- 1 2 3 Blakinger, Keri (July 19, 2016) "A look back at when Nazis lived on Long Island – and ran a brutal indoctrination camp plagued by sexual assault" New York Daily News

- 1 2 Wesselhoeft, Conrad (March 25, 1984) "Where L.I. Nazis Camped" The New York Times

- 1 2 3 Eltman, Fred (May 20, 2017) "New York enclave with Nazi roots agrees to change policies" Associated Press

- ↑ Staff (August 15, 1938) "40,00 at Nazi Camp Fete" The New York Times

- ↑ Staff (July 17, 1938) "Camp Siegfried Loses" The New York Times

- 1 2 3 Young, Michelle (April 2, 2015) "Long Island with Adolf Hitler Street Still Exists" Untapped Cities

- ↑ Staff (July 12, 1940) "Bund Quits Camp Group" The New York Times

- ↑ Staff (August 14, 1941) "Yaphank Renounces Hitler Street Name" The New York Times

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Yaphank, New York. |