Xuzhou

| Xuzhou 徐州市 | |

|---|---|

| Prefecture-level city | |

|

The skyline of Xuzhou and Yunlong Lake (云龙湖) | |

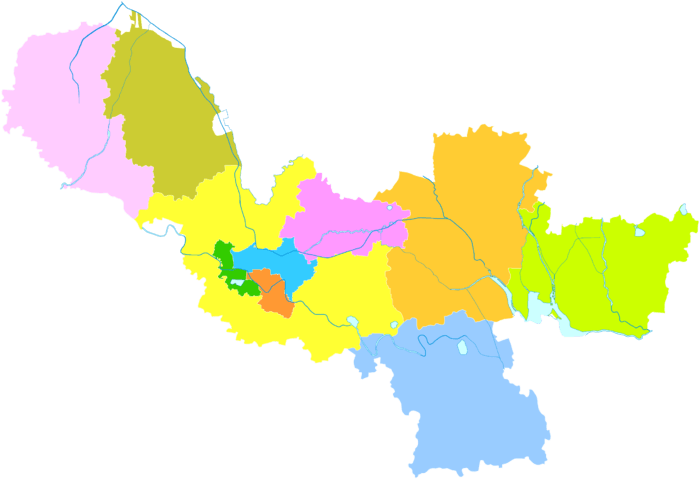

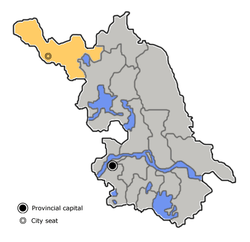

Location of Xuzhou City jurisdiction in Jiangsu | |

Xuzhou Location in China | |

| Coordinates: 34°16′N 117°13′E / 34.26°N 117.21°ECoordinates: 34°16′N 117°13′E / 34.26°N 117.21°E | |

| Country | China |

| Province | Jiangsu |

| County-level divisions | 10 |

| Township-level divisions | 161 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Zhou Tiegen (周铁根) |

| • CPC Committee Secretary | Zhang Guohua (张国华) |

| Area | |

| • Prefecture-level city | 11,259 km2 (4,347 sq mi) |

| • Urban | 3,037 km2 (1,173 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 2,347 km2 (906 sq mi) |

| Population (2010 census) | |

| • Prefecture-level city | 8,577,225 |

| • Density | 760/km2 (2,000/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 3,053,778 |

| • Urban density | 1,000/km2 (2,600/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 2,623,066 |

| • Metro density | 1,100/km2 (2,900/sq mi) |

| Time zone | China Standard (UTC+8) |

| Postal code | 221000(Urban center), 221000, 221000, 221000(Other areas) |

| Area code(s) | 0516 |

| GDP | ¥ 532 billion (2015) |

| GDP per capita | ¥ 62,000 (2015) |

| Major Nationalities | Han |

| Licence plate prefixes | 苏C |

| Website |

xz |

| Xuzhou | |||||||||

|

"Xuzhou", as written in Chinese | |||||||||

| Chinese | 徐州 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Postal | Suchow | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Pengcheng | |||||||||

| Chinese | 彭城 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Xuzhou, known as Pengcheng in ancient times, is a major city in and the fourth largest prefecture-level city of Jiangsu Province, China. Its population was 8,577,225 at the 2010 census whom 2,623,066 lived in the built-up (or metro) area made of Quanshan, Gulou, Yunlong and Tongshan districts.[1] It is known for its role as a transportation hub in northwestern Jiangsu, as it has expressways and railway links connecting directly to the provinces of Henan and Shandong, the neighboring port city of Lianyungang, as well as the economic hub Shanghai.

Romanization

Before the adoption of Hanyu Pinyin, the city's name was typically romanized as Suchow[2] or Süchow,[3][4] though it also appeared as Siu Tcheou [Fou],[5] Hsu-chou,[6] Hsuchow,[7] and Hsü-chow.[4][8]

History

Early history

According to the archaeological excavations, the early prehistoric relics around Xuzhou are classified as Dawenkou culture system. Liulin (劉林) site together with Dadunzi (大墩子) site, Huating (花廳) site, and Liangwangcheng (梁王城) site correspond to the initial, middle and late stages of this culture, respectively.[9] As far the edge of the suburb, remains of sacrificial activities to Houtu were found at Qiuwan (丘灣) site and Gaohuangmiao (高皇廟) site, Tongshan. Extrapolating from the findings, the archaeologists reckoned they belong to Shang dynasty.[10] Besides, history relates that Peng or Great Peng, the transitions from a tribe to a chiefdom, dominated the partial area of Xuzhou nowadays, which eventually conquered by King Wu Ding of Shang in around 1208 BC.[11][12] While Peng Zu is believed to be the first chief.

During the Western Zhou, a chiefdom called Xuyi or Xu rose and controlled the Lower Yellow River Valley. Allied with Huaiyi, Xuyi fought against Zhou and its vassals at irregular intervals. Since its declining, Xuyi once moved the capital to the area of Xuzhou and populated it with people who were migrated southwards.

After Song annexed the area, the first actual city in Xuzhou according to chronicles, was built. The name Pengcheng was given to it. In 573 BC, Chu and Zheng invaded Song and captured Pengcheng.[13] Soon afterwards, the city was recaptured. Shared its territory among them, Song eventually exterminated by Qi, Chu and Wei in 286 BC. Chu got the part which in the north of the Huai River. Before that, Chu saw the area as their natural sphere of influence due to the growing influence. Xuzhou and its west neighbouring region were referred to as West Chu. Since its realm shrunk, Chu moved its capital to this area in 278 BC after the Qin army captured its old one, Ying, in modern Jingzhou, Hubei. Moreover, there were two minor states called Pi and Zhongwu in then east of Xuzhou during the Spring and Autumn period.

Imperial China

The domino effect caused by the Dazexiang Uprising is enormous. Xiang Liang, one of the main rebel leaders, made a bid for recognized authority by reconstituting the old kingdom of Chu, choosing as king a grandson of a former ruler. The capital city of the new kingdom was established at Pengcheng.[14] After Liang's death, his nephew, Xiang Yu won the overlordship from power struggle, he proclaimed himself the Hegemon-King of Western Chu and kept Pengcheng as a capital until defeated by Liu Bang in 202 BC.

.jpg)

Liu Bang, first emperor of the Han Dynasty (206 BC−AD 220), was born in Pei County, Xuzhou. At the beginning of the Han Dynasty, Xuzhou became part of the Kingdom of Chu, a principality ruled by relatives of the royal Liu family. Initially, Liu Bang allowed his relatives to rule parts of the country since they were assumed to be the most trustworthy. However, the Kingdom of Chu under third generation ruler Liu Wu rebelled against the central authority during the Rebellion of the Seven Princes and was defeated. His tomb was recently excavated near Xuzhou. Perhaps the earliest reliable evidence of the presence of Buddhism in China could be found in Pengcheng, which was the seat of Liu Ying, the Prince of Chu when the Emperor Ming of Han reigned. Ying had both Taoist and Buddhist faith, he also supported some monks and even kept them around him, according to a letter to him from the Emperor, which was quoted in the Book of the Later Han:

楚王誦黃老之微言,尚浮屠之仁祠,潔齋三月,與神為誓,何嫌何疑,當有悔吝?其還贖以助伊蒲塞桑門之盛饌。[15]

The letter was wrote in 65 AD, before Buddhism was introduced formally in 68. By the end of the 2nd century, a prosperous community had been settled at Pengcheng.[16]

In 193, Cao Cao attacked Pengcheng and the others cites of Xu Province. Then Cao and his enemies controlled Xuzhou alternately until he defeated Liu Bei in 200.

The invasions of the Five Barbarians posed a great threat to the local residents. With considerable households migrated to the south of the Yangtze River since the 3rd century, Xu Province was lost and became a migrated province. Its capital moved to Jingkou, namely Zhenjiang nowadays, from Pengcheng also. The old province where then Pengcheng was located was prefixed "North" to distinguish. Until Liu Yu recaptured there in 421, reversion ensued.

The raging wars inflicted upon Xuzhou until the Emperor Taizong of Tang's enthronement in 626. Keeping the northern rebellions and warfare a distance gave Xuzhou scope for developing during the most period of the Tang Dynasty. According to the Old Book of Tang and the New book of Tang, in 639, the total population of Pengcheng County, Fei County and Pei County was only 21,768, versus 205,286 in 742.[17]

In 781, General Li Na rebelled, but his cousin Li Wei (李洧) as the prefect of Xuzhou, refused to cooperate with him. Na was angry at that and commanded his army to lay siege to the city of Xuzhou. Several days afterwards, the imperial authority's force arrived and defeated Na. Na's rebel made it was necessary to reinforce defence in Xuzhou for the court.[18] In 788, Zhang Jianfeng, the prefect of Xuzhou at the time, was appointed as the first military governor (or Jiedushi,節度使) of Xuzhou-Sizhou-Haozhou (徐泗濠節度使) whose headquarters was still at Xuzhou. The title was invalid since 800, but was restored and rename Wuning (武寧) in 805. In consideration of Wang Zhxing's sterling war record, the court granted him formal appointment to Wuning in the spring of 822. He recruited about 2000 brutal soldiers to garrison the city, Wang's successors mostly were came from the civil officer system, made they incapable of controlling these soldiers increasingly.[19] The Wuning army also became notorious, the garrison even expelled its governor, Wen Zhang (溫璋), in 862.[20] Meantime, they revolted twice in 849 and 859.[21]

Then Wang Shi (王式) replaced Wen. Wang suppressed the garrison and disintegrated the Wuning army. Far from settling matters, this simply produced a new and more difficult problem, for the soldiers who had fled or were banished from the city began to terrorize the surrounding area as bandits. The next year, 864, the court declared an amnesty in the area, and promised that all former soldiers who willingly re-enrolled would be sent for a tour of duty in the southern.[22] Coincidentally, it was these people beset the court several years later.[23] In 868, about 800 soldiers stationed at Guizhou (Guilin nowadays) and, led by their provisions officer Pang Xun, began to march back north, the extended service and abuse from their chief contributed to their furious desertion. The court decided to pardon the revolt, and to allow the soldiers to return home under escort, provided they surrendered their arms halfway. Having done so, the soldiers, suspecting that the court's pardon was probably only a trick to get them off their guard and that they would be attacked on the way back to their hometowns or else killed when they returned, took steps to re-arm themselves.[24] Pang's troop captured Xuzhou and also the extensive area around the prefecture by 869, but eventually defeat by the court's army in the end of this year. Consequently, thousands people were executed.[25] Whereas the court had to restore the Wuning army again in the next year, they also hope the army don't stir up trouble any more, thus, it was renamed "Ganhua (感化)", whose rough meaning in Chinese is "reformatory" or "moral exhortation".[26]

After the Yellow River began to change course during the Song Dynasty (AD 960−1279), heavy silting at the Yellow River estuary forced the river to channel its flow into the lower Huai River tributary. The area became barren thereafter due to persistent flooding, nutrient depletion and salination of the once fertile soil.

After the Jingkang incident, Wanyan Zonghan's army marched to the Yangtze River in 1129, meanwhile he ordered his subordinate Nijuhun to storm Xuzhou. On February 17, Nijuhun occupied Xuzhou after a 27-days siege, and the guarding governor Wang Fu was executed (王复) for refusing to surrender. Wang's successor Zhao Li (赵立) regrouped his forces and raided the enemy. He achieved an enormous victory, however, as a strategic decision, he evacuated from Xuzhou with soldiers and citizens, went south to rescue the siege of Chuzhou in the end of this year.[27] Henceforth, Xuzhou was ruled by Jurchen over a century.

In 1232, the general Wang You (王佑), Feng Xian (封仙) revolted, they expelled the Jurchen's governor Tuktan. Then the Mongolian army led by Anyong (安用), a Han Chinese general captured Xuzhou soon. Both the general of Suzhou (宿州) Liu Anguo (刘安国) and the general of Pizhou Du Zheng (杜政) yielded their owned city to Anyong. Regarding Anyong's behave as grabbing reputation, the Mongolian general Asuru (阿术鲁/额苏伦 in Chinese) irritated and persisted to kill him. Felt panic, Anyong sought refuge from Jurchen.[28] The Jin Dynasty resumed its ruling in Xuzhou, and it was quite transient. The serious disunity made betraying recur. On November 1233, the garrison of Xuzhou welcomed the Mongolian.[29] Meantime, Anyong pledged loyalty to the Song Dynasty. He captured the city again after the Mongolian army left. In the spring of the next year, the Mongolian commander Zhang Rong (张荣) attacked Xuzhou,[30] Anyong drowned himself after the final defeat.[28] The Mongolian governor of Xuzhou and Pizhou called Li Gaoge (李杲哥) surrendered to the Song in 1262. Then he failed and was killed after several days.[31]

An uneasy calm settled over Xuzhou during the most time of the Yuan Dynasty (1271−1368), but it was broken completely by the waves of insurrection since 1350s. A rebellion headed by Li Er (李二), or was known as his nickname: Sesame Li (芝麻李) rose in Xuzhou subsequent to the Red Turban Rebellion.[32] The imperial court issued an ultimatum to them with a 20-days deadline, it proved to be ineffectual. Then Toqto'a led a successful expedition in 1352 to recapture the city. It was the symbolically most important campaigns he chose to command in person.[33] And his troops not only put Li's followers down with appalling barbarity but also massacred the citizens brutally.[34] Zhang Shicheng occupied Xuzhou in 1360 as the most northerly city of his domain.[35] The Hongwu Emperor's general Xu Da , captured Xuzhou in the summer of 1366. Then his subordinates Fu Youde (傅友德) and Lu Ju (陸聚) beat Köke Temür in the vicinity of the city.[32]

Xuzhou had been a hub for both the national courier system and the grain tribute system for several centuries.[36] It played a more prominent role after the Yongle Emperor ambitiously planned to move imperial capital to Beijing. Aimed at holding this vital hub, three garrison areas, namely Guards, or also Wei (衛) in Chinese, were established in modern Xuzhou's area: Xuzhou Guard (徐州衛), Xuzhou Left Guard (徐州左衛), Pizhou Guard (邳州衛), while more than 10,000 soldiers were stationed there. Granaries collecting the tribute grain destined for the capital were also established in Xuzhou when the Yongle Emperor reigned.[37] The flourishing economy largely attributed to the carriage, especially by the Grand Canal,[38] one of seven customs barriers (or customs houses, 鈔關) under the Ministry of Revenue was located in Xuzhou.[39] It was retained until the late Qing.[40]

Choe Bu, a Korean official, who passed Xuzhou along the Grand Canal in 1488, his book, the Geumnam pyohaerok writes:

The cities in the north of the Yangtze River, such as Yangzhou, Huai'an, and the ones in the north of the Huai River, such as Xuzhou, Jining, Linqing, are prosperous and bustling just like the Jiangnan region...

(江以北,若揚州、淮安及淮河以北,若徐州、濟寧、臨清,繁華豐阜,無異江南……)

However, two Rapids: the Xuzhou Rapids (徐州洪), a kilometer southeast of Xuzhou, and the Lüliang Rapids (呂梁洪), another 24 kilometers further south were threats for vessels and sailors.[41] In 1604, the Jia River was repaired to link Weishan Lake and the Yellow River rounding two Rapids as the new stretch of the Grand Canal, which gave a shock for local development.

One of areas constantly susceptible to famine was Xuzhou. Here famine struck in 1441. There was serious flooding in 1452, 1453, 1456, and 1457, and in 1458 there was again widespread famine. What's worse, the harshness of the climate led to more severe flood and drought alternately in almost every year, was a torture for the prefecture since 15th century.[42]

Shi Kefa was appointed as the Minister of War when the Prince of Fu was crowned as the Hongguang Emperor in 1644. He designated four defense commanders including the former bandit general Gao Jie (高傑). Now, as Shi redeployed the commanders and other units, Gao took the crucial forward position at Xuzhou.[43] In response to the situation, the Ming court had ordered its best units forward, repulsing the Qing armies and designating new defense areas all along the southern bank of the Yellow River (江北四鎮). But the assassination of Gao seriously reduced the court's capacity to deal with further Qing challenges.[44] Gao's successor was an amoral general, Li Chengdong (李成棟). Being aware of forthcoming attack, he deserted Xuzhou in the early summer of 1645. Then Dodo's army captured the city.

.jpg)

The Tancheng earthquake in 1688 involved Xuzhou, its disastrous consequence was recorded by the local chorography:[45]

City walls,government offices and also residents' houses, mostly were ruined, and the collapsing buildings around the area led to enormous deaths...

(城垣、官署、民廬傾覆過半,遠近壓死人不可數計……)

Then many people were living outside or in shacks, and the circumstances were restored after several months.

The tragic process whereby the Yellow River shifted its course from the southern to the northern side began in 1851 with a series of damaging floods that inundated broad reaches of Xuzhou and its environs. Though it was not until August 1855 that there occurred the massive break in the dikes that released the river north-eastward, the years from 1851 brought ruin and famine. These years of economic desperation exacerbated the endemic malaise of inter-community feuding, a circumstance of some significance for intensifying Nian movement. Felt obliged, Zeng Guofan rushed to Xuzhou and commanded the troops. The army of Nian attempted to attack the city in the following decade for several times, but all in vain.

Modern China

Zhang Xun fled into Xuzhou with the remnants of his force, after the Uprising. They entered the city on 5 December 1911. A rifle platoon of garrison revolted on 7 February 1912. Since most of force had been flattened by the assaults, Zhang escaped to Yanzhou. On 11 February, the Revolutionary Army captured the area and disestablished the prefecture.

Yuan Shikai rearmed Zhang's army, then the latter returned and recaptured Xuzhou in the summer of the next year. They cracked down the republicans remained and continue their push towards Nanjing. Thereafter Zhang's headquarters was established in Xuzhou, he summoned the rest leaders of Beiyang clique to the conference for four times. Zhang involved the stalemate among Li Yuanhong and Duan Qirui in 1917. He marched towards Beijing at the head of a large force on 7 June. His failure spread and caused a terrible wave of theft and arson committed by his garrisons later in Xuzhou in July.

In the early Warlord Era, Xuzhou was Anhui clique's domain. But the area changed hands several times in the 1920s. Fengtian clique, Zhili clique and National Revolutionary Army controlled the area, successively.[46] As the leader of the Northern Expedition, Chiang Kai-shek arrived in Xuzhou on 17 June 1927. He conferred with Feng Yuxiang and other Kuomintang officers on 20 June, Feng was courted by Nanjing.[47] Then Sun Chuanfang and Zhang Zongchang began to fight in unison against the Nationalist government. They captured the city on 24 June. The fall of Xuzhou arouse public outrage, Chiang 's first resignation ensued. On 16 December, Nanjing force took the area again.[48]

The area was the site both of the Battle of Xuzhou in 1938 against the Japanese Army in the Second Sino-Japanese War and of the critical battle in the Chinese Civil War, the Huaihai Campaign in 1948-49. The capitulation of Chiang Kai-shek to Chinese communist forces at Xuzhou[49] led to the fall of the Nationalist Chinese capital Nanking.

On May 19, 1938, Chiang gave order to abandoned Xuzhou, then Japanese military controlled the city. They set up a puppet regime, North Jiangsu Prefectural Commission (苏北行政长官公署) in 1939.

In 1942, the Reorganized National Government took over Xuzhou from Japanese military superficially and divided several counties of the northern Jiangsu and Bozhou into Suhuai Special Regions. Then it converted as Huaihai Province, and its capital was Xuzhou. Hao Pengju was appointed as the governor.[50]

On August 3, 1945. Two U.S. bombers had intended to knock out the Japanese arsenal, but bombed a fair for misjudgment, which led to about 700 citizens deaths. On September 7, 19th Army Group of the National Revolutionary Army, Chen Ta-ching's troop arrived in Xuzhou and garrisoned. Then more National Revolutionary Army arrived to control Jinpu Railway against CPC. In the same year, the urban area of Tongshan County at that time was spun off into Xuzhou City. On November 16, Xuzhou Prefectural Government was founded. On December 21, Xuzhou Pacification Commission (徐州绥靖公署) was founded.

During the Second Sino-Japanese War, Japanese Army committed sorts of crime in and around Xuzhou. The Nationalist Government founded Xuzhou court-martial for Japanese war criminals affiliated to Xuzhou Pacification Commission on February 15, 1946. There were 25 war criminals at the trials, and 8 were executed finally, including two Koreans.[51][52]

On February 10, 1946, Guo Yingqiu as the respective of CPC attended the conference with the government for peace, but it was futile. On March 2, George Marshall, Zhang Zhizhong and Zhou Enlai arrived at Xuzhou for further negotiation, got no effect, still. The National Revolutionary Army in Xuzhou began to attacked the area controlled by CPC since May, they marched along the railways and moved forward. Xu Yue was the director of Xuzhou Pacification Commission who commanded these troops. Gu Zhutong replace him to gassioned Xuzhou as the Commanding General of Army in the next year, while Xuzhou Pacification Commission was converted into Xuzhou Command Headquarters affiliated to the General Headquarters. Chiang even ordered Yasuji Okamura to Xuzhou as military adviser.

Xuzhou Command Headquarters was reorganised as General Suppression Headquarters of Xuzhou Garrison on June 14, 1948, while Liu Chih was the Commanding General and Du Yuming was the Deputy. The PLA attacked the area around Xuzhou to besiege the city in November. On December 1, they captured it. The Huaihai Campaign ended on January 10, 1949, KMT still controlled remaining region of Jiangsu, hence, Shandong Province administrated Xuzhou and Lianyungang of the time temporarily. Although the period was short (1949–52), the followed impacts on Xuzhou was lasting. For instance, Xuzhou Railway Branch Administration affiliated to Jinan Railway Administration from then on until transferring to Shanghai in 2008.

During the Cultural Revolution, the railway system of most China was collapsed, especially in Xuzhou, which was noticed by Beijing. In 1975, Deng Xiaoping sent Wan Li as the minister of railways to Xuzhou on mission to restore order.[53]

On April 22, 1993, Xuzhou was ratified as "Larger Municipality" with legislative power by the State Council.[54]

Administration

The evolutionary history

| The evolutionary history of Xuzhou's administrative division | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Period | Provincial Level | Prefectural Level | County Level | ||||

| Spring and Autumn |

Song (state) 宋国 |

Pengcheng 彭城 Liuyi 留邑 Lüyi 吕邑 | |||||

| Zhongwu (state) 钟吾国 | |||||||

| Warring States |

Chu (state) 楚国 | Peiyi 沛邑 | |||||

| Qi (state) 齐国 | Changyi 常邑 | ||||||

| Pi (state) 邳国 | |||||||

| Qin dynasty | Sishui Commandery 泗水郡 |

Pei County 沛县 Pengcheng County 彭城县 Liu County 留县 Xiao County 萧县 | |||||

| Donghai Commandery 东海郡 | Xiapi County下邳县 | ||||||

| Western Han | Xu Province 徐州(古代,刺史部) |

Chu (state) 楚国 | Lü County 吕县 Wuyuan County 武原县 | ||||

| Donghai Commandery 东海郡 |

Siwu County 司吾县 Marquis Jianling’s state 建陵侯国 Marquis Liangcheng’s state 良成侯国 Marquis Rongqiu’s state 容丘侯国 | ||||||

| Yu Province 豫州(古代,刺史部) |

Pei Commandery 沛郡 |

Pei County 沛县 Feng County 丰县 Guangqi County 广戚县 | |||||

| Eastern Han and Three Kingdoms |

Xu Province 徐州(古代,刺史部) |

Pengcheng (state) 彭城国 |

Pengcheng County 彭城县 Liu County 留县 <Lü County 吕县 Wuyuan County 武原县 Guangqi County 广戚县 | ||||

| Xiapi (state) 下邳国 |

Xiapi County 下邳县 Liangcheng County 良成县 Siwu County 司吾县 | ||||||

| Yu Province 豫州(古代,刺史部) |

Pei (state) 沛国 |

Pei County 沛县 Feng County 丰县 | |||||

| Jin dynasty, Northern and Southern dynasties |

(Nouth) Xuzhou or (Nouth) Xu Province (北)徐州 South Xuzhou or South Xu Province 南徐州, located in modern Zhenjiang, see Zhenjiang |

Pengcheng Commandery 彭城郡 |

Pengcheng County 彭城县 Liu County 留县 Lü County 吕县 | ||||

| Xiapi Commandery 下邳郡 |

Xiapi County 下邳县 Liangcheng County 良成县 Siwu County 司吾县 | ||||||

| Pei Commandery 沛郡 |

Pei County 沛县 Feng County 丰县 | ||||||

| Jiyin Commandery 济阴郡 |

Suiling County 睢陵县 | ||||||

| Sui dynasty | Pengcheng Commandery 彭城郡 |

Pengcheng County 彭城县 Liu County 留县 Pei County 沛县 Feng County 丰县 | |||||

| Xiapi Commandery 下邳郡 |

Xiapi County 下邳县 Liangcheng County 良城县 | ||||||

| Tang dynasty | Henan Circuit 河南道 |

Xuzhou 徐州 |

Pengcheng County 彭城县 Pei County 沛县 Feng County 丰县 | ||||

| Sizhou 泗州 | Xiapi County 下邳县 | ||||||

| Northern Song |

West Jingdong Circuit 京东西路 |

Xuzhou 徐州 |

Pengcheng County 彭城县 Pei County 沛县 Feng County 丰县 Baofeng Jian* 宝丰监 Liguo Jian* 利国监 | ||||

| East Jingdong Circuit 京东东路 |

Huaiyang Military 淮阳军 |

Xiapi County 下邳县 | |||||

| Jin | West Shandong Circuit 山东西路 |

Xuzhou 徐州 | Pengcheng County 彭城县 Feng County 丰县 | ||||

| Huaiyang Military 淮阳军 | Xiapi County 下邳县 | ||||||

| Tengzhou 滕州 | Pei County 沛县 | ||||||

| Yuan dynasty | Henanjiangbei Province 河南江北行中书省 |

Gui’de-fu 归德府 |

Xuzhou 徐州 | Xiao County 萧县 | |||

| Pizhou 邳州 | Xiapi County 下邳县 Suining County 睢宁县 | ||||||

| Branch Secretariats 中书省 |

Jining Circuit 济宁路 |

Jizhou 济州 | Pei County 沛县 | ||||

| Feng County 丰县 | |||||||

| Ming dynasty | Nanquin/South Zhil 南京/南直隶 |

Xuzhou (as a Independent Departments) 徐州 |

Pei County 沛县 Feng County 丰县 Xiao County 萧县 Dangshan County 砀山县 | ||||

| Huaian-fu淮安府 | Pizhou 邳州 | ||||||

| Qing dynasty, during 1733-1911 |

Kiangsu/Jiangsu Province 江苏省 |

Xuzhou-fu (as a Prefecture) 徐州府 |

Tongshan County 铜山县 Pei County 沛县 Feng County 丰县 Xiao County 萧县 Dangshan County 砀山县 Suining County 睢宁县 Suqian County 宿迁县 Pizhou 邳州 | ||||

| Republic of China, during 1945-1949 |

Kiangsu/Jiangsu Province 江苏省 |

Xuzhou City 徐州市 | |||||

| No.9 Administrative Superintendent District 第九督察区 |

Tongshan County 铜山县 Pei County 沛县 Feng County 丰县 Xiao County 萧县 Dangshan County 砀山县 Suining County 睢宁县 Pi County 邳县 | ||||||

| People's Republic of China, during 1949-1952 |

Shandong Province 山东省 |

Xuzhou City徐州市 | Tongshan County 铜山县 | ||||

| Prefecture of Teng County 滕县专区 |

Tongbei County 铜北县 Pei County 沛县 Feng County 丰县 | ||||||

| Prefecture of Linyi 临沂专区 |

Pi County 邳县 | ||||||

| Administrative Region of the Northern Anhui 皖北行署区 |

Prefecture of Su County 宿县专区 |

Xiao County 萧县 Dangshan County 砀山县 | |||||

| People's Republic of China, in 1955 |

Jiangsu Province 江苏省 |

Xuzhou City 徐州市 |

Gulou District 鼓楼区 Yunlong District 云龙区 Zifang District 子房区 Wangling District 王陵区 Jiawang Mining District 贾汪矿区 | ||||

| Prefecture of Xuzhou 徐州专区 |

Xinhailian City 新海连市 Tongshan County 铜山县 Pei County 沛县 Feng County 丰县 Suining County睢宁县 Pi County 邳县 Xinyi County 新沂县 Donghai County 东海县 Ganyu County 赣榆县 | ||||||

| Anhui Province 安徽省 |

Prefecture of Su County 宿县专区 |

Xiao County 萧县 Dangshan County 砀山县 | |||||

| People's Republic of China, in 1963 |

Jiangsu Province 江苏省 |

Xuzhou City 徐州市 |

Gulou District 鼓楼区 Yunlong District 云龙区 Jiawang Town 贾汪镇 The Suburb 郊区(办事处) | ||||

| Prefecture of Xuzhou 徐州专区 |

Tongshan County 铜山县 Pei County 沛县 Feng County 丰县 Suining County睢宁县 Pi County 邳县 Xinyi County 新沂县 Donghai County 东海县 Ganyu County 赣榆县 | ||||||

| People's Republic of China, in 1983 |

Jiangsu Province 江苏省 |

Xuzhou City 徐州市 |

Gulou District 鼓楼区 Yunlong District 云龙区 The Suburb District 郊区 Jiawang District 贾汪区 The Mining District 矿区 Tongshan County 铜山县 Pei County 沛县 Feng County 丰县 Suining County睢宁县 Pi County 邳县 Xinyi County 新沂县 | ||||

| Lianyungang City 连云港市 |

Donghai County 东海县 Ganyu County 赣榆县 | ||||||

| People's Republic of China, in 1993 |

Jiangsu Province 江苏省 |

Xuzhou City 徐州市 |

Gulou District 鼓楼区 Yunlong District 云龙区 Quanshan District 泉山区 Jiawang District 贾汪区 The Mining District 矿区 Pizhou City 邳州市 Xinyi City 新沂市 Tongshan County 铜山县 Pei County 沛县 Feng County 丰县 Suining County 睢宁县 | ||||

| People's Republic of China, 2010–present |

Jiangsu Province 江苏省 |

Xuzhou City 徐州市 |

Gulou District 鼓楼区 Yunlong District 云龙区 Quanshan District 泉山区 Jiawang District 贾汪区 Tongshan District 铜山区 Pizhou City 邳州市 Xinyi City 新沂市 Pei County 沛县 Feng County 丰县 Suining County 睢宁县 | ||||

The present administrative division

The prefecture-level city of Xuzhou administers ten county-level divisions, including five districts, two county-level cities and three counties. These are further divided into 161 township-level divisions, including 63 subdistricts and 98 towns.[55]

| Map | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Map | Hanzi | Pinyin | Population (2010) | Area (km2) | Density | ||

| City Proper | |||||||

| Yunlong District | 云龙区 | Yúnlóng Qū | 1,536,502 | 438 | 3,508 | ||

| Gulou District | 鼓楼区 | Gúlóu Qū | |||||

| Quanshan District | 泉山区 | Quánshān Qū | |||||

| Suburban | |||||||

| Tongshan District | 铜山区 | Tóngshān Qū | 1,086,564 | 1,909 | 569 | ||

| Jiawang District | 贾汪区 | Jiǎwāng Qū | 430,712 | 690 | 624.22 | ||

| Rural | |||||||

| Suining County | 睢宁县 | Suíníng Xiàn | 1,039,315 | 1,767 | 588.01 | ||

| Pei County | 沛县 | Pèi Xiàn | 1,141,935 | 1,349 | 847 | ||

| Feng County | 丰县 | Fēng Xiàn | 963,531 | 1,446 | 666 | ||

| Satellite cities (County-level cities) | |||||||

| Pizhou | 邳州市 | Pīzhōu Shì | 1,458,038 | 2,088 | 698 | ||

| Xinyi | 新沂市 | Xīnyí Shì | 920,628 | 1,571 | 586 | ||

| Total | 8,577,225 | 11,259 | 762 | ||||

Geography

Geology, Landform and Hydrology

The geologic structure of Xuzhou consisting of four parts from east to west, more precisely, they belong to the Shandong-Jiangsu Traps (鲁苏地盾), the Tancheng-Lujiang Fault Zone (郯庐断裂带), the Xu-Huai Downwarp-fold Belt (徐淮坳褶带) and the Fault-block of West Shandong (鲁西断块) respectively. It was formed during the Archean Eon and maintains relatively stable since then.[56]

Most area of Xuzhou is located in the Xu-Huai Alluvial Plain (徐淮黄泛平原), the southeast part of the North China Plain.

There is a zone along the old course of Yellow River covered with sediment through the area.

The city proper is bisected by the ancient channel of Yellow River, while Yunlong Lake (云龙湖) is located in the its southwest.

Luoma Lake, located on the Xinyi-Suqian boundaries, is the main resource of tap water for Xuzhou since 2016.

Climate

Xuzhou has a monsoon-influenced humid subtropical climate (Köppen Cwa), with cool, dry winters, warm springs, long, hot and humid summers, and crisp autumns. The monthly daily average temperature ranges from 0.4 °C (32.7 °F) in January to 27.1 °C (80.8 °F) in July; the annual mean is 14.48 °C (58.1 °F). Snow may occur during winter, though rarely heavily. Precipitation is light in winter, and a majority of the annual total of 832 millimetres (32.8 in) occurs from June thru August. With monthly percent possible sunshine ranging from 44% in July to 54% in three months, the city receives 2,221 hours of bright sunshine annually.

The lowest temperature recorded in Xuzhou was -23.3 °C, on 6 February 1969, while the highest was 43.4 °C, on 15 July 1955.[57]

| Climate data for Xuzhou (1971−2000) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 19.8 (67.6) |

25.9 (78.6) |

30.1 (86.2) |

34.8 (94.6) |

38.2 (100.8) |

40.6 (105.1) |

43.4 (110.1) |

38.2 (100.8) |

36.2 (97.2) |

34.5 (94.1) |

29.0 (84.2) |

21.3 (70.3) |

43.4 (110.1) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 5.2 (41.4) |

7.8 (46) |

13.4 (56.1) |

20.9 (69.6) |

26.3 (79.3) |

30.4 (86.7) |

31.4 (88.5) |

30.6 (87.1) |

26.9 (80.4) |

21.5 (70.7) |

14.1 (57.4) |

7.7 (45.9) |

19.7 (67.4) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 0.4 (32.7) |

2.7 (36.9) |

8.0 (46.4) |

15.1 (59.2) |

20.6 (69.1) |

25.0 (77) |

27.1 (80.8) |

26.3 (79.3) |

21.7 (71.1) |

15.7 (60.3) |

8.5 (47.3) |

2.6 (36.7) |

14.5 (58.1) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −3.3 (26.1) |

−1.4 (29.5) |

3.2 (37.8) |

9.8 (49.6) |

15.1 (59.2) |

20.2 (68.4) |

23.5 (74.3) |

22.7 (72.9) |

17.4 (63.3) |

10.9 (51.6) |

4.0 (39.2) |

−1.6 (29.1) |

10.0 (50.1) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −17.3 (0.9) |

−23.3 (−9.9) |

−7.6 (18.3) |

−1.4 (29.5) |

4.8 (40.6) |

12.4 (54.3) |

15.9 (60.6) |

13.4 (56.1) |

5.0 (41) |

−1.0 (30.2) |

−8.3 (17.1) |

−13.5 (7.7) |

−23.3 (−9.9) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 17.6 (0.693) |

20.5 (0.807) |

36.0 (1.417) |

47.1 (1.854) |

65.5 (2.579) |

106.8 (4.205) |

241.0 (9.488) |

132.6 (5.22) |

72.3 (2.846) |

51.5 (2.028) |

26.7 (1.051) |

14.0 (0.551) |

831.6 (32.739) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 4.0 | 5.4 | 6.4 | 7.1 | 7.4 | 8.0 | 13.5 | 9.9 | 7.2 | 6.8 | 5.1 | 3.7 | 84.5 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 66 | 64 | 62 | 62 | 64 | 67 | 80 | 81 | 74 | 70 | 69 | 66 | 68.8 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 144.8 | 147.5 | 177.0 | 210.5 | 232.7 | 218.6 | 191.9 | 202.8 | 188.3 | 190.8 | 164.2 | 151.8 | 2,220.9 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 46 | 48 | 48 | 54 | 54 | 51 | 44 | 49 | 51 | 54 | 53 | 50 | 50.2 |

| Source: China Meteorological Administration[58] | |||||||||||||

Natural disasters

The earthquakes seldom affected Xuzhou historically, except for the 462 Yanzhou earthquake and 1668 Tancheng earthquake, which caused enormous losses and casualties, while the epicenters rarely located in this area.

Demographics

According to the 1% National Population Sample Survey in 2015, the total resident population of Xuzhou reached 8.66 millions, and the sex ratio was 101.40 males to 100 females.[59]

| Year | Urban areas | Tongshan | Feng | Pei | Suining | Pizhou | Xinyi | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1913 | 826,083 | 291,562 | 280,345 | 501,867 | 636,040 | 2,535,897 | ||

| 1918 | 854,213 | 281,696 | 294,604 | 506,975 | 639,064 | 2,576,552 | ||

| 1928 | 954,939 | 308,968 | 329,933 | 508,226 | 568,193 | 2,670,259 | ||

| 1932 | 986,536 | 304,480 | 346,593 | 547,848 | 584,904 | 2,770,361 | ||

| 1935 | 1,099,296 | 364,007 | 391,121 | 645,890 | 642,641 | 3,142,955 | ||

| 1953 | 333,190 | 1,072,430 | 473,815 | 395,094 | 653,854 | 683,113 | 452,203 | 4,063,699 |

| 1964 | 505,417 | 1,001,377 | 587,822 | 575,237 | 729,619 | 861,117 | 518,086 | 4,778,675 |

| 1982 | 779,289 | 1,414,460 | 834,568 | 869,778 | 981,917 | 1,187,526 | 741,600 | 6,809,138 |

| 1990 | 949,267 | 1,741,522 | 952,760 | 1,042,280 | 1,160,772 | 1,431,728 | 883,650 | 8,161,979 |

| 2002 | 1679626 | 1,262,489 | 1,068,404 | 1,183,048 | 1,217,820 | 1,539,922 | 962,656 | 8,913,965 |

| 2010 | 1,911,585 | 1,142,193 | 963,597 | 1,141,935 | 1,042,544 | 1,458,036 | 920,610 | 8,580,500 |

Economy

Earlier development

Xuzhou is a vital hub for freight, especially during the Ming and Qing dynasties. The city once benefited from waterborne freight without reckoning on the war eras, however, its traditional economic economy was nearly ruined after the Yellow River flooded and changed its course in 1855 and the abandon of the Caoyun system.

.jpg)

The Yellow River not only affect trading but also farming. The main cereal crop cultivated in Xuzhou used to be Japonica rice, however, as the impact of the river made the area dry-farming, they became really rare at least during the mid-Qing. On the eve of Revolution of 1911, wheat, soya bean and peanut were widely planted.

The mining and metallurgy in Xuzhou began quite early. According to the archaeological site at Liguo, a town in northern Xuzhou, there were furnaces for iron constructed during the Han dynasty. A triangle-edge copper mirror with carved divine beasts was found in the Kurozuka Kofun (黒塚古墳) which located at Tenri, Japan, and it was engraved with inscriptions: "Copper from Xuzhou; craftman from Luoyang" in Chinese (“銅出徐州;師出洛陽”). Hence its material is believed to fabricated probably in Xuzhou during the Three Kingdoms period.[60] There is another similar mirror found in Liaoyang's ancient tombs. The Song's Government set up Liguo Bureau (or Liguo Jian, 利國監) to smelt iron in 979, while Baofeng Bureau (or Baofeng Jian, 寶豐監) was order to mint coins since 1083.[61][62][63] The coals of Xuzhou were discovered when Su Shi as the local governor, then they were utilized to smelt Liguo's iron ore, replaced the charcoal. Su even wrote a poem entitled The coals (石炭) to record this event, which shows that the coal industry of Xuzhou initiated no later than 1079.

Modern times

From 1910s to 1940s, the staple merchandise for sale were peanut, soya bean, soya bean meal, wheat, sesame, sunflower seed, daylily, alive swine and pelt. Meanwhile, the ones for purchase were fabric, cotton yarn, sugar, salt, cigarettes, kerosene, etc. And the main domestic trades were associating with Nanjing and Shanghai.

As the railways extended to Xuzhou, the city appeared to be prospering again, and it opened to foreign traders formally in 1922,[64] still, only quite a few small and medium-sized shops were operating, on account of the continual warfare. Meanwhile, the industrial structure had to adapt itself to a war economy. Distilled beverage industry in Xuzhou was single flourishing sector since the Japanese military purchased the liquor from practitioners as an alternative to alcohol during the Second Sino-Japanese War. Likewise the lodging industry from 1945 to 1949, it grew rapidly as massing of KMT's troops. Besides, the finance was also in disorder. On November, 1933, recession and over-issue of the local notes triggered a run on local banks, which gummed up whole regional commercial activities.

The early modern mining in Xuzhou could be considered as a minor product of the Self-Strengthening Movement since 1881. It struggled on into the 20 century. CPC's industrial policy once made it blossomed and brought a main satellite city, Jiawang. The whole area possesses about 93% of the Jiangsu coals reserves.[56] In 1970, Datun mining area was put under Shanghai administration for providing adequate coals.

When Zhang Xun occupied Xuzhou, he ordered to build a power station in the north of the city. Its 40-kilowatt generator started in 1914, which made Xuzhou became one of the few cities with electricity. On August 1, 1941, a power plant whose installed capacity was 1250 kilowatts completed in Jiawang. The power industry gained great progress after 1949. Installed capacity of the Xuzhou Plant up to 13,000,000 kilowatts in 1985.[65]

During the planned economy period, the coal and electric power industries reinforced their importance while the main manufacture were metallic materials, chemicals and mining machines. The city was defined as one of the old industrial bases after the Chinese economic reform.

Nowadays, the most important industries of Xuzhou are machinery, energy and food production. Wheat-maize rotation is quite widespread since the 20th century while the main contemporary fruit yield are apple and pear, besides, peach, grape, pomegranate and apricot are also common. Ginkgo tree is another economic plant.

The construction machinery manufacturer XCMG is the largest company based in Xuzhou. It is the world's tenth-largest construction equipment maker measured by 2011 revenues, and the third-largest based in China (after Sany and Zoomlion).[66]

Education

By the imperial era, Xuzhou was nearly barren of education resources, in comparison with Jiangnan. In 1903, a traditional academy being turned into public primary school, was the beginning of modernising the local education. Even in Republican China, only a limited number of underfunded schools was available. There were only two colleges: Provincial College of Kiangsu (省立江蘇學院) and North China Theological Seminary, besides 19 urban middles school in 1948.[67]

This impoverishment is reversed since the 1950s. In 1958, Jiangsu Normal Academy relocated to Xuzhou. And then Nanjing Medical College, Xuzhou Branch was founded in July. Both of the institutions have been preserved after the Great Leap Forward. In 1978, then China Institute of Mining and Technology relocated to Xuzhou from the West of China.

Schools

- Xuzhou No.1 Middle School (徐州市第一中学)

- Xuzhou No.2 Middle School (徐州市第二中学)

- Xuzhou No.3 Middle School (徐州市第三中学)

- Xuzhou Senior High School (徐州市高级中学)

- Xuzhou No.5 Middle School

- Xuzhou No.36 Middle School (徐州市第三十六中学)

- Xuzhou No.13 Middle School (徐州市第十三中学)

Universities and colleges

- China University of Mining and Technology

- Jiangsu Normal University

- Xuzhou Medical University

- Xuzhou Institute of Technology

- People's Liberation Army Engineering Corps Command College (中国人民解放军工程兵指挥学院)

- People's Liberation Army Air Force Logistical College (中国人民解放军空军后勤学院)

Scenic spots

Tourist attractions in Xuzhou include Yunlong Mountain (Cloud Dragon Mountain) and the nearby Yunlong Lake, which are near the downtown area. There are also Xuzhou Museum and Han Dynasty Stone Carvings museum next to the Yunlong Mountain.

The most important places of interest in Xuzhou are the relics of Han Dynasty, including Terracotta Army of Han, Mausoleum of the kings of Han and the art of stone graving.

Religion

According to the local administrator's survey in 2014, around 4.76% of the population of Xuzhou, namely 0.46 million people belongs to organised religions.The largest groups being Protestants with 350,000 people, followed by Buddhists with 70,000 people.

Catholicism

.jpg)

Despite being guaranteed the religious liberty, the initial missionary work was held up by stout resistance in the 1880s. The involvement of a secret society escalated regional disputes, known as "Xuzhou Missionary Cases", in the next decade. Especially in 1896, thousands of rioters destroyed almost all the local churches. While the riots were deemed as retaliation for missionaries' villainy.

The missionary work before 1918, on the whole, dominated by Jesuits in France. Then more French-Canadians arrived in Xuzhou to assist their French brethren. They even started the magazine titled 'Le Brigand'', the early articles of that revolve around their work. Apostolic Prefecture of Süchow established in 1931, it was promoted as a Diocese in 1946.

The local missionary work at its zenith in 1938. There were about 68,000 Catholics, 365 mission schools with about 10,050 students. The Japanese changed such a success.[68] Bishop Philip Côté who refused to cooperate with the government was exiled in 1953. While the rest of missions left in the next year.[69]

Protestantism

Later in the 1880s, Alfred G. Jones reached Xuzhou and worked as a Baptist minister. Made slow progress, he turned to American Southern Presbyterian Mission before he left. Hugh W.White was sent to Xuzhou. He returned with Mark Grier in 1896, after an enforced absence. Then Frank A.Brown, E. H. Hamilton, L. S. Morgan and others joined them. Brown as the last foreign Protestant missionary departed from Xuzhou in the spring of 1949.[70]

Culture

Arts

According to Xu Wei's Nanci Xulu (南詞敘錄; [Treatises and Catalogue of Nanqu]), Yuyao Tone (余姚腔), one of then major Southern Operas, was prevalent in Xuzhou during the Mid-Ming period. Shanxi merchants popularized Bangzi in Xuzhou afterwards, since it was introduced in the late Ming along the Great Cannel. Fused the local ballads in dialect, this localized version evolved into a new opera over the following centuries. The opera was designated as Jiangsu Bangzi (江蘇梆子) in 1962.

The new municipal concert hall was opened in 2011, shaped like a myrtle flower. However, the various regular performances are unattainable. While the first local philharmonic orchestra is established in 2015.

Media

The first local newspaper entitled Hsing-hsü Daily (醒徐日報) was started in 1913. Nowadays, Xuzhou's major newspaper is Xuzhou Daily (徐州日報), which was founded in the end of 1948. It is owned and operated by the Xuzhou Committee of the Communist Party of China.[71]

| Station | Chinese name | Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| News Radio | 新闻广播 | 93 FM |

| Private Motor Radio | 私家车广播 | 91.6 FM |

| Traffic Radio | 交通广播 | 103.3 FM |

| Joy Radio | 文艺广播 | 89.6 FM |

| Channel | Chinese name | Description |

|---|---|---|

| XZ·1 | 徐州·1 | News & General |

| XZ·2 | 徐州·2 | Economy & Life |

| XZ·3 | 徐州·3 | Arts & Entertainment |

| XZ·4 | 徐州·4 | Public |

The earliest local radio was broadcasting in 1934 for public education. Then Japanese military founded Hsuchow Broadcasting Station (徐州放送局; Joshi Hōsōkyoku) in 1938, after the city was captured. The National Army took over it after the World War II. Broadcasting was resumed in 1949, operated by the CPC. In 1980, Xuzhou TV Station was established. A decade later, Xuzhou TV Tower was completed.

Museums

Dialect

As a subdialect of Central Plains Mandarin, Xuzhou dialect is spoken in the whole area, especially in the suburb and countryside.

Cuisine

Xuzhou cuisine is closely related to Shandong cuisine's Jinan-style. Xuzhou's most well known foods include bǎzi ròu (pork belly, and other items stewed in a thick broth), sha tang (![]() 汤), and various dog meat dishes.

汤), and various dog meat dishes.

Another one of Xuzhou's famous dishes is di guo (地锅) style cooking which places ingredients with a spicy sauce in a deep black skillet and cooks little pieces of flatbread on the side or top. Common staples of di guo style cooking include: chicken, fish, lamb, pork rib and eggplant.

Fu Yang Festival (伏羊节) is a traditional festival celebrated in the city. It starts on Chufu (初伏) which is around mid-July and lasts for about one month. During the festival, people eat lamb meat and drink lamb soup. This festival is very popular among all the citizens.

Transport

Roads

Expressways

- G2 Beijing–Shanghai Expressway

- G2513 Huai'an–Xuzhou Expressway

- G3 Beijing–Taipei Expressway

- G30 Lianyungang–Khorgas Expressway

- S49 Xinyi–Yangzhou Expressway

- S65 Xuzhou–Mingguang Expressway

- S69 Jinan–Xuzhou Expressway

National Highway

- China National Highway 104

- China National Highway 205

- China National Highway 206

- China National Highway 311

Rail

Xuzhou is one of the most important railway hubs in China. Xuzhou has two main railway stations: Xuzhou Railway Station and Xuzhou East Railway Station. Xuzhou Railway Station is one of the largest Chinese railway stations, it is the interchange station of Jinghu Railway, Longhai Railway. Xuzhou East Railway Station lies in the eastern suburb of Xuzhou, which is the hub of Beijing–Shanghai High-Speed Railway and Xuzhou–Lanzhou High-Speed Railway.

Its satellite city Xinyi has a smaller hub, Xinyi Railway Station is the terminus of Jiaozhou–Xinyi Railway and Xinyi–Changxing Railway.

Aviation

Xuzhou Guanyin Airport serves the area with scheduled passenger flights to major airports in China including Beijing, Shanghai, Nanjing, Hong Kong and many other cities.

A general airport will be finished in Xinyi by 2017.[72]

Public transportation

Xuzhou is the first city in North Jiangsu to build a subway system. The project was approved by State Council in 2013. 3 subway lines are being built and expected to be completed by 2019-2020 one after another, with total length of 67 km.

Xuzhou has a public bicycle system for citizens since 2012.

The others

The Grand Canal flows through Xuzhou, and the navigation route extends from Jining to Hangzhou.

Luning oil pipeline, which originates from Shandong Linyi (临邑) County to Nanjing, passes through Xuzhou.

Military

Xuzhou is headquarters of the 12th Group Army of the People's Liberation Army, one of the three group armies that compose the Nanjing Military Region responsible for the defense of China's eastern coast and possible military engagement with Taiwan. The People's Liberation Army Navy also has a Type 054A frigate that shares the name of the region.

See also

- List of twin towns and sister cities in China

- Battle of Xuzhou

- List of cities in the People's Republic of China by population

- Xuzhou dialect

Notes

- ↑ http://www.citypopulation.de/php/china-jiangsu-admin.php

- ↑ Postal romanization, See, e.g., this 1947 ROC map.

- ↑ Rosario Renaud, Süchow. Diocèse de Chine 1882-1931, Montréal, 1955.

- 1 2 Canadian Missionaries, Indigenous Peoples: Representing Religion at Home and Abroad. University of Toronto Press. 2005. p. 208.

- ↑ Louis Hermand, Les étapes de la Mission du Kiang-nan 1842-1922 et de la Mission de Nanking 1922-1932, Shanghai, 1933.

- ↑ See: Wade-Giles.

- ↑ Jaques, Tony (2007). Dictionary of Battles and Sieges: P-Z. p. 1116.

- ↑ Twitchett, Fairbank (2009). The Cambridge History of China, Vol. 5: The Sung Dynasty and Its Precursors, 960-1279 AD, Part I. Cambridge University Press. p. 1042. ISBN 978-0521812481.

- ↑ "江苏邳州梁王城遗址大汶口文化遗存发掘简报 (Brief Excavation Report of the Remains of Dawenkou Culture at the Site of Liangwangcheng in Pizhou, Jiangsu Province)" (PDF). 东南文化 (Southeast Culture). 2013(4): 21–41.

- ↑ Yu, Weichao. "銅山丘湾商代社祀遗迹的推定". 考古 (Archaeology). 1973(5): 296–298.

- ↑ (武丁……四十三年,王師滅大彭。) 竹書紀年(Bamboo Annals)

- ↑ (彭、豕韋為商伯矣。當週未有……彭姓彭祖、豕韋、諸稽,則商滅之矣。) 國語(Guoyu)·卷十六,鄭語

- ↑ (夏六月,鄭伯侵宋,及曹門外。遂會楚子伐宋,取朝郟。楚子辛、鄭皇辰侵城郜,取幽丘,同伐彭城,納宋魚石、向為人、鱗朱、向帶、魚府焉,以三百乘戍之而還.) 左傳(Zuo zhuan)·成公,成公十八年

- ↑ Twitchett, Loewe (1987), p. 114.

- ↑ "后汉书·卷四十二".

- ↑ Twitchett, Loewe (1987), p. 670.

- 1 2 Jiangsu Provincial Chorographies: Demography Chorography (in Chinese). Nanjing: Jiangsu Guji Press. 1999. ISBN 7-80122-5260.

- ↑ Twitchett (2007), p. 593.

- ↑ Twitchett (2007), p. 541.

- ↑ Twitchett (2007), p. 516, 557.

- ↑ Twitchett (2007), p. 687, 697.

- ↑ Twitchett (2007), p. 558, 697.

- ↑ Twitchett (2007), p. 696.

- ↑ Twitchett (2007), p. 697.

- ↑ "资治通鉴·卷二百五十一".

- ↑ Twitchett (2007), p. 727.

- ↑ "宋史·列传第二百七".

- 1 2 "金史·列传第五十五".

- ↑ "金史·列传第五十一".

- ↑ "元史·列传第三十七".

- ↑ "元史·列传第三十五".

- 1 2 "明史·本纪第一".

- ↑ Franke, Twitchett (2006). The Cambridge History of China, Vol. 6: Alien regimes and border states, 907-1368. Cambridge University Press. p. 577. ISBN 978-0-521-24331-5.

- ↑ "元史·列传第二十五".

- ↑ "明史·列传第十一".

- ↑ Twitchett, Mote (1998), p. 590.

- ↑ Twitchett, Mote (1998), p. 500.

- ↑ Twitchett, Mote (1998), p. 598.

- ↑ Twitchett, Mote (1998), p. 603.

- ↑ Peterson (2002). The Cambridge History of China, Vol. 9: The Ch'ing Empire to 1800, Part I. Cambridge University Press. p. 647. ISBN 0 521 24334 3.

- ↑ Twitchett, Mote (1998), p. 599.

- ↑ Mote, Twitchett (2007). The Cambridge History of China, Vol. 7: The Ming Dynasty, 1368-1644, Part I. Cambridge University Press. p. 310. ISBN 978-0-521-24332-2.

- ↑ Mote, Twitchett (2007). The Cambridge History of China, Vol. 7: The Ming Dynasty, 1368-1644, Part I. Cambridge University Press. p. 633. ISBN 978-0-521-24332-2.

- ↑ Mote, Twitchett (2007). The Cambridge History of China, Vol. 7: The Ming Dynasty, 1368-1644, Part I. Cambridge University Press. p. 656. ISBN 978-0-521-24332-2.

- ↑ "徐州会发生地震吗?".

- ↑ Fairbank (2005). The Cambridge History of China, Vol. 9: Republican China 1912-1949, Part I. Cambridge University Press. p. 651. ISBN 978-0-521-23541-9.

- ↑ Fairbank (2005). The Cambridge History of China, Vol. 9: Republican China 1912-1949, Part I. Cambridge University Press. p. 665. ISBN 978-0-521-23541-9.

- ↑ Fairbank (2005). The Cambridge History of China, Vol. 9: Republican China 1912-1949, Part I. Cambridge University Press. p. 700. ISBN 978-0-521-23541-9.

- ↑ "Battle of Suchow". Life Magazine, December 6, 1948.

- ↑ Jiangsu Provincial Chorographies: Civil Administration Chorography. Beijing: China Local Records Publishing. 2002.

- ↑ "徐州绥靖公署军事法庭审判日本战犯回顾(in Chinese)".

- ↑ "不能忘却的审判(in Chinese)".

- ↑ "1975,万里在徐州整顿铁路(in Chinese)".

- ↑ "国务院关于同意苏州市和徐州市为"较大的市"的批复".

- ↑ "徐州市区划简册(2016)".

- 1 2 "Jiangsu Provincial Geography" (in Chinese). Beijing: Beijing Normal University Publishing Group. 2011. ISBN 9787303131686.

- ↑ "沂沭泗流域介绍(in Chinese)".

- ↑ 中国地面国际交换站气候标准值月值数据集(1971-2000年) (in Chinese). China Meteorological Administration. June 2011. Archived from the original on September 21, 2013. Retrieved 2010-05-27.

- ↑ "The bulletin of 1% National Population Sample Survey in Xuzhou 2015 's main data".

- ↑ "黒塚古墳(in Japanese)".

- ↑ (徐州…… 監二:寶豐,元豐六年置,鑄銅錢,八年廢。利國。主鐵冶。) 宋史(History of Song)·誌第三十八 地理一

- ↑ (徐州則置寶豐……元豐以後,西師大舉,邊用匱闕,徐州置寶豐下監,歲鑄折二錢二十萬緡……自熙寧以來……复徐州寶豐、衛州黎陽監,並改鑄折二錢為折十……) 宋史(History of Song)·誌第一百三十三,食貨下二

- ↑ (癸卯,詔:「京城外置錢監,並複徐州寶豐監、衛州黎陽監,並改鑄當十大錢,其當二限一年,更不行使。」) 續資治通鑑長編拾補·卷二十三.

- ↑ "Jiangsu Provincial Chorographies: Comprehensive Economy Chorography" (in Chinese). Nanjing:Jiangsu Guji Press. Retrieved 2016-07-23.

- ↑ Jiangsu Provincial Chorographies: Electricity Industry Chorography. Nanjing: Jiangsu Science&Technology Press. 1994. ISBN 7-5345-1844-X.

- ↑ "Analysis: China's budding Caterpillars break new ground overseas". Reuters. 8 March 2012. Retrieved 8 March 2012.

- ↑ Zhao (2015), pp. 222–247.

- ↑ "Le financement canadien-français de la mission chinoise des Jésuites au Xuzhou de 1931 à 1949" (PDF) (in French).

- ↑ "天主教在徐州传播的概况".

- ↑ "近现代基督教在徐州地区的传播".

- ↑ "Jiangsu Provincial Chorographies: Press Chorography" (in Chinese). Nanjing:Jiangsu Guji Press.

- ↑ "徐州新沂通用机场建设工程环境影响评价第一次公示".

References

- Twitchett, Loewe, Denis, Michael (1987). The Cambridge History of China, Volume 1: The Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 BC–AD 220. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-24327-8.

- Twitchett, Denis (2007). The Cambridge History of China, Volume 3: Sui and T'ang China, 589–906, Part 1. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-21446-9.

- Twitchett, Mote, Denis, Frederick W. (1998). The Cambridge History of China, Volume 8: The Ming Dynasty, 1368–1644, Part 2. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-24333-9.

- Zhao, Liangyu (2015). 环境·经济·社会——近代徐州城市社会变迁的研究(1882–1948). China Social Sciences Press. ISBN 978-7-516-16418-1.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Xuzhou. |

- Government website of Xuzhou (in Simplified Chinese)

- Xuzhou city guide with open directory (Jiangsu.NET)

| Largest cities or towns in China Sixth National Population Census of the People's Republic of China (2010) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Name | Province | Pop. | Rank | Name | Province | Pop. | ||

Shanghai .jpg) Beijing |

1 | Shanghai | Shanghai | 20,217,700 | 11 | Foshan | Guangdong | 6,771,900 |  Chongqing  Guangzhou |

| 2 | Beijing | Beijing | 16,858,700 | 12 | Nanjing | Jiangsu | 6,238,200 | ||

| 3 | Chongqing | Chongqing | 12,389,500 | 13 | Shenyang | Liaoning | 5,890,700 | ||

| 4 | Guangzhou | Guangdong | 10,641,400 | 14 | Hangzhou | Zhejiang | 5,578,300 | ||

| 5 | Shenzhen | Guangdong | 10,358,400 | 15 | Xi'an | Shaanxi | 5,399,300 | ||

| 6 | Tianjin | Tianjin | 10,007,700 | 16 | Harbin | Heilongjiang | 5,178,000 | ||

| 7 | Wuhan | Hubei | 7,541,500 | 17 | Dalian | Liaoning | 4,222,400 | ||

| 8 | Dongguan | Guangdong | 7,271,300 | 18 | Suzhou | Jiangsu | 4,083,900 | ||

| 9 | Chengdu | Sichuan | 7,112,000 | 19 | Qingdao | Shandong | 3,990,900 | ||

| 10 | Hong Kong | Hong Kong | 7,055,071 | 20 | Zhengzhou | Henan | 3,677,000 | ||