Gel

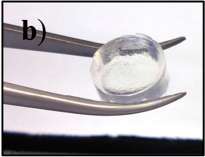

A gel is a solid jelly-like material that can have properties ranging from soft and weak to hard and tough. Gels are defined as a substantially dilute cross-linked system, which exhibits no flow when in the steady-state.[1] By weight, gels are mostly liquid, yet they behave like solids due to a three-dimensional cross-linked network within the liquid. It is the crosslinking within the fluid that gives a gel its structure (hardness) and contributes to the adhesive stick (tack). In this way gels are a dispersion of molecules of a liquid within a solid in which the solid is the continuous phase and the liquid is the discontinuous phase. The word gel was coined by 19th-century Scottish chemist Thomas Graham by clipping from gelatine.[2]

Composition

Gels consist of a solid three-dimensional network that spans the volume of a liquid medium and ensnares it through surface tension effects. This internal network structure may result from physical bonds (physical gels) or chemical bonds (chemical gels), as well as crystallites or other junctions that remain intact within the extending fluid. Virtually any fluid can be used as an extender including water (hydrogels), oil, and air (aerogel). Both by weight and volume, gels are mostly fluid in composition and thus exhibit densities similar to those of their constituent liquids. Edible jelly is a common example of a hydrogel and has approximately the density of water.

Polyionic polymers

Polyionic polymers are polymers with an ionic functional group. The ionic charges prevent the formation of tightly coiled polymer chains. This allows them to contribute more to viscosity in their stretched state, because the stretched-out polymer takes up more space. This is also the reason gel hardens. See polyelectrolyte for more information.

Types

Hydrogels

A hydrogel is a network of polymer chains that are hydrophilic, sometimes found as a colloidal gel in which water is the dispersion medium. Hydrogels are highly absorbent (they can contain over 90% water) natural or synthetic polymeric networks. Hydrogels also possess a degree of flexibility very similar to natural tissue, due to their significant water content. The first appearance of the term 'hydrogel' in the literature was in 1894.[4] Common uses for hydrogels include:

- Scaffolds in tissue engineering. When used as scaffolds, hydrogels may contain human cells to repair tissue. They mimic 3D microenvironment of cells.[5]

- Hydrogel-coated wells have been used for cell culture[6]

- Environmentally sensitive hydrogels (also known as 'Smart Gels' or 'Intelligent Gels'). These hydrogels have the ability to sense changes of pH, temperature, or the concentration of metabolite and release their load as result of such a change.[7]

- Sustained-release drug delivery systems

- Providing absorption, desloughing and debriding of necrotic and fibrotic tissue

- Hydrogels that are responsive to specific molecules, such as glucose or antigens, can be used as biosensors, as well as in DDS.[8]

- Disposable diapers where they absorb urine, or in sanitary napkins[9]

- Contact lenses (silicone hydrogels, polyacrylamides, polymacon)

- EEG and ECG medical electrodes using hydrogels composed of cross-linked polymers (polyethylene oxide, polyAMPS and polyvinylpyrrolidone)

- Water gel explosives

- Rectal drug delivery and diagnosis

- Encapsulation of quantum dots

- Breast implants

- Glue

- Granules for holding soil moisture in arid areas

- Dressings for healing of burn or other hard-to-heal wounds. Wound gels are excellent for helping to create or maintain a moist environment.

- Reservoirs in topical drug delivery; particularly ionic drugs, delivered by iontophoresis (see ion exchange resin).

- Materials mimicking animal mucosal tissues to be used for testing mucoadhesive properties of drug delivery systems[10][11]

Common ingredients include polyvinyl alcohol, sodium polyacrylate, acrylate polymers and copolymers with an abundance of hydrophilic groups.

Natural hydrogel materials are being investigated for tissue engineering; these materials include agarose, methylcellulose, hyaluronan, and other naturally derived polymers.

Hydrogels show promise for use in agriculture, as they can release agrochemicals including pesticides and phosphate fertiliser slowly, increasing efficacy and reducing runoff, and at the same time improve the water retention of drier soils such as sandy loams.[12]

Organogels

An organogel is a non-crystalline, non-glassy thermoreversible (thermoplastic) solid material composed of a liquid organic phase entrapped in a three-dimensionally cross-linked network. The liquid can be, for example, an organic solvent, mineral oil, or vegetable oil. The solubility and particle dimensions of the structurant are important characteristics for the elastic properties and firmness of the organogel. Often, these systems are based on self-assembly of the structurant molecules.[13][14] (An example of formation of an undesired thermoreversible network is the occurrence of wax crystallization in petroleum.[15])

Organogels have potential for use in a number of applications, such as in pharmaceuticals,[16] cosmetics, art conservation,[17] and food.[18]

Xerogels

A xerogel /ˈzɪəroʊˌdʒɛl/ is a solid formed from a gel by drying with unhindered shrinkage. Xerogels usually retain high porosity (15–50%) and enormous surface area (150–900 m2/g), along with very small pore size (1–10 nm). When solvent removal occurs under supercritical conditions, the network does not shrink and a highly porous, low-density material known as an aerogel is produced. Heat treatment of a xerogel at elevated temperature produces viscous sintering (shrinkage of the xerogel due to a small amount of viscous flow) and effectively transforms the porous gel into a dense glass.

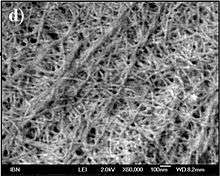

Nanocomposite hydrogels

Nanocomposite hydrogels[19][20] are also known as hybrid hydrogels, can be defined as highly hydrated polymeric networks, either physically or covalently crosslinked with each other and/or with nanoparticles or nanostructures. Nanocomposite hydrogels can mimic native tissue properties, structure and microenvironment due to their hydrated and interconnected porous structure. A wide range of nanoparticles, such as carbon-based, polymeric, ceramic, and metallic nanomaterials can be incorporated within the hydrogel structure to obtain nanocomposites with tailored functionality. Nanocomposite hydrogels can be engineered to possess superior physical, chemical, electrical, and biological properties.[19]

Properties

Many gels display thixotropy – they become fluid when agitated, but resolidify when resting. In general, gels are apparently solid, jelly-like materials. By replacing the liquid with gas it is possible to prepare aerogels, materials with exceptional properties including very low density, high specific surface areas, and excellent thermal insulation properties.

Animal-produced gels

Some species secrete gels that are effective in parasite control. For example, the long-finned pilot whale secretes an enzymatic gel that rests on the outer surface of this animal and helps prevent other organisms from establishing colonies on the surface of these whales' bodies.[21]

Hydrogels existing naturally in the body include mucus, the vitreous humor of the eye, cartilage, tendons and blood clots. Their viscoelastic nature results in the soft tissue component of the body, disparate from the mineral-based hard tissue of the skeletal system. Researchers are actively developing synthetically derived tissue replacement technologies derived from hydrogels, for both temporary implants (degradable) and permanent implants (non-degradable). A review article on the subject discusses the use of hydrogels for nucleus pulposus replacement, cartilage replacement, and synthetic tissue models.[22]

Applications

Many substances can form gels when a suitable thickener or gelling agent is added to their formula. This approach is common in manufacture of wide range of products, from foods to paints and adhesives.

In fiber optics communications, a soft gel resembling "hair gel" in viscosity is used to fill the plastic tubes containing the fibers. The main purpose of the gel is to prevent water intrusion if the buffer tube is breached, but the gel also buffers the fibers against mechanical damage when the tube is bent around corners during installation, or flexed. Additionally, the gel acts as a processing aid when the cable is being constructed, keeping the fibers central whilst the tube material is extruded around it.

A hydrogel used to coat an RNA triple-helix including a tumor suppressor miRNA and an antagomiR (oncomiR inhibitor) offers a promising way to treat tumors such as breast cancer. The treatment could be delivered in a prophylactic patch which combines gene, chemo- and phototherapy.[23][24][25]

See also

- 2-Acrylamido-2-methylpropane sulfonic acid

- Agarose gel electrophoresis

- Food rheology

- Gel electrophoresis

- Gel filtration chromatography

- Gel permeation chromatography

- Hydrocolloid

- Ouchterlony double immunodiffusion

- Paste (rheology)

- Polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- Radial immunodiffusion

- Silicone gel

- Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis

- Void (composites)

References

- ↑ Ferry, John D. (1980) Viscoelastic Properties of Polymers. New York: Wiley, ISBN 0471048941.

- ↑ Harper, Douglas. "Online Etymology Dictionary: gel". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 2013-12-09.

- ↑ Kwon, Gu Han; Jeong, Gi Seok; Park, Joong Yull; Moon, Jin Hee; Lee, Sang-Hoon (2011). "A low-energy-consumption electroactive valveless hydrogel micropump for long-term biomedical applications". Lab on a Chip. 11 (17): 2910–5. PMID 21761057. doi:10.1039/C1LC20288J.

- ↑ "Der Hydrogel und das kristallinische Hydrat des Kupferoxydes". Zeitschrift für Chemie und Industrie der Kolloide. 1 (7): 213–214. 1907. doi:10.1007/BF01830147.

- ↑ Mellati, Amir; Dai, Sheng; Bi, Jingxiu; Jin, Bo; Zhang, Hu (2014). "A biodegradable thermosensitive hydrogel with tuneable properties for mimicking three-dimensional microenvironments of stem cells". RSC Adv. 4 (109): 63951–63961. ISSN 2046-2069. doi:10.1039/C4RA12215A.

- ↑ Discher, D. E.; Janmey, P.; Wang, Y.L. (2005). "Tissue Cells Feel and Respond to the Stiffness of Their Substrate". Science. 310 (5751): 1139–43. Bibcode:2005Sci...310.1139D. PMID 16293750. doi:10.1126/science.1116995.

- ↑ Brudno, Yevgeny (2015-12-10). "On-demand drug delivery from local depots". Journal of Controlled Release. 219: 8–17. PMID 26374941. doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.09.011. Retrieved 21 March 2017.

- ↑ Yetisen, A. K.; Naydenova, I; Da Cruz Vasconcellos, F; Blyth, J; Lowe, C. R. (2014). "Holographic Sensors: Three-Dimensional Analyte-Sensitive Nanostructures and their Applications". Chemical Reviews. 114 (20): 10654–96. PMID 25211200. doi:10.1021/cr500116a.

- ↑ Caló, Enrica; Khutoryanskiy, Vitaliy V. (2015). "Biomedical applications of hydrogels: A review of patents and commercial products". European Polymer Journal. 65: 252–267. doi:10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2014.11.024.

- ↑ Cook, Michael T.; Smith, Sarah L.; Khutoryanskiy, Vitaliy V. (2015). "Novel glycopolymer hydrogels as mucosa-mimetic materials to reduce animal testing". Chem. Commun. 51 (77): 14447–14450. doi:10.1039/C5CC02428E.

- ↑ Cook, Michael T.; Khutoryanskiy, Vitaliy V. (2015). "Mucoadhesion and mucosa-mimetic materials—A mini-review". International Journal of Pharmaceutics. 495 (2): 991–8. PMID 26440734. doi:10.1016/j.ijpharm.2015.09.064.

- ↑ Puoci, Francesco; et al. (2008). "Polymer in Agriculture: A Review" (PDF). American Journal of Agricultural and Biological Sciences. 3 (1): 299–314.

- ↑ Terech P. (1997) "Low-molecular weight organogelators", pp. 208–268 in: Robb I.D. (ed.) Specialist surfactants. Glasgow: Blackie Academic and Professional, ISBN 0751403407.

- ↑ van Esch J., Schoonbeek F., De Loos M., Veen E.M., Kellog R.M., Feringa B.L. (1999) "Low molecular weight gelators for organic solvents", pp. 233–259 in: Ungaro R., Dalcanale E. (eds.) Supramolecular science: where it is and where it is going. Kluwer Academic Publishers, ISBN 079235656X.

- ↑ Visintin RF, Lapasin R, Vignati E, D'Antona P, Lockhart TP (2005). "Rheological behavior and structural interpretation of waxy crude oil gels". Langmuir. 21 (14): 6240–9. PMID 15982026. doi:10.1021/la050705k.

- ↑ Kumar, R; Katare, OP (2005). "Lecithin organogels as a potential phospholipid-structured system for topical drug delivery: A review". AAPS PharmSciTech. 6 (2): E298–310. PMC 2750543

. PMID 16353989. doi:10.1208/pt060240.

. PMID 16353989. doi:10.1208/pt060240. - ↑ Carretti E, Dei L, Weiss RG (2005). "Soft matter and art conservation. Rheoreversible gels and beyond". Soft Matter. 1: 17. Bibcode:2005SMat....1...17C. doi:10.1039/B501033K.

- ↑ Pernetti M, van Malssen KF, Flöter E, Bot A (2007). "Structuring of edible oils by alternatives to crystalline fat". Current Opinion in Colloid & Interface Science. 12 (4–5): 221–231. doi:10.1016/j.cocis.2007.07.002.

- 1 2 Gaharwar, Akhilesh K.; Peppas, Nicholas A.; Khademhosseini, Ali (March 2014). "Nanocomposite hydrogels for biomedical applications". Biotechnology and Bioengineering. 111 (3): 441–453. PMC 3924876

. PMID 24264728. doi:10.1002/bit.25160.

. PMID 24264728. doi:10.1002/bit.25160. - ↑ Carrow, James K.; Gaharwar, Akhilesh K. (November 2014). "Bioinspired Polymeric Nanocomposites for Regenerative Medicine". Macromolecular Chemistry and Physics. 216 (3): 248–264. doi:10.1002/macp.201400427.

- ↑ Dee, Eileen May; McGinley, Mark and Hogan, C. Michael (2010). "Long-finned pilot whale" in Saundry, Peter and Cleveland, Cutler (eds.) Encyclopedia of Earth. National Council for Science and the Environment. Washington DC.

- ↑ "Injectable Hydrogel-based Medical Devices: "There's always room for Jell-O"1". Orthoworld.com. September 15, 2010. Retrieved 2013-05-19.

- ↑ Conde, J; Oliva, N; Atilano, M; Song, HS; Artzi, N (2015). "Self-assembled RNA-triple-helix hydrogel scaffold for microRNA modulation in the tumour microenvironment". Nat Mater. 15 (3): 353–63. Bibcode:2016NatMa..15..353C. PMID 26641016. doi:10.1038/nmat4497.

- ↑ Conde, J; Oliva, N; Artzi, N (Mar 2015). "Implantable hydrogel embedded dark-gold nanoswitch as a theranostic probe to sense and overcome cancer multidrug resistance". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 112 (11): E1278–87. Bibcode:2015PNAS..112E1278C. PMC 4371927

. PMID 25733851. doi:10.1073/pnas.1421229112.

. PMID 25733851. doi:10.1073/pnas.1421229112. - ↑ Conde, João; Oliva, Nuria; Zhang, Yi; Artzi, Natalie (2016). "Local triple-combination therapy results in tumour regression and prevents recurrence in a colon cancer model". Nature Materials. 15 (10): 1128–38. PMID 27454043. doi:10.1038/nmat4707.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gels. |

| Look up gel in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

-solution.jpg)