Alprazolam

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | Alprazolam /ælˈpræzəlæm/ or /ælˈpreɪzəlæm/, Xanax /ˈzænæks/ |

| Trade names | Xanax, Niravam |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a684001 |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Dependence liability | Physical: Moderate Psychological: High[1] |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 80–90% |

| Metabolism | Hepatic, via cytochrome P450 3A4 |

| Biological half-life |

Immediate release: 11.2 hours,[2] Extended release: 10.7–15.8 hours[2] |

| Excretion | Renal |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.044.849 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

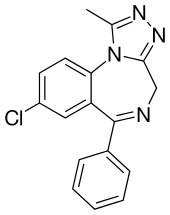

| Formula | C17H13ClN4 |

| Molar mass | 308.77 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Alprazolam, available under the trade name Xanax, is a potent, short-acting benzodiazepine anxiolytic—a minor tranquilizer.[3] It is commonly used for the treatment of anxiety disorders, especially of panic disorder, but also in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) or social anxiety disorder.[4][5] It was the 12th most prescribed medicine in the United States in 2010.[6] Alprazolam, like other benzodiazepines, binds to specific sites on the GABAA receptor. It possesses anxiolytic, sedative, hypnotic, skeletal muscle relaxant, anticonvulsant, amnestic, and antidepressant properties.[7] Alprazolam is available for oral administration as compressed tablets (CT) and extended-release capsules (XR).

Peak benefits achieved for generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) may take up to a week.[8][9] Tolerance to the anxiolytic and antipanic effects is controversial, with only some authoritative sources supporting the development of tolerance;[4][10][11] tolerance will, however, develop to the sedative and hypnotic effects within a couple of days.[11] Withdrawal symptoms or rebound symptoms may occur after ceasing treatment abruptly following a few weeks or longer of steady dosing, and may necessitate a gradual dose reduction.[8][12] Other risks include increased rates of suicide, possibly due to disinhibition.[13]

Alprazolam was first released by Upjohn (now a part of Pfizer) in 1981.[14] The first approved use was of panic disorder, and within two years of its original marketing, Xanax became a blockbuster drug in the US. As at 2010, alprazolam is the most prescribed[15] and the most misused benzodiazepine in the US.[16] The potential for misuse among those taking it for medical reasons is controversial, with some expert reviews stating that the risk is low and similar to that of other benzodiazepine drugs.[4] Others state that there is a substantial risk of misuse and dependence in both patients and non-medical users and that the high affinity binding, high potency, short elimination half-life, and rapid onset of action may increase the misuse potential of alprazolam.[10][17] Compared to the large number of prescriptions, relatively few individuals increase their dose on their own initiative or engage in drug-seeking behavior.[18] Alprazolam is classified as a Schedule IV controlled substance by the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA).

Medical uses

Alprazolam is mostly used to treat anxiety disorders, panic disorders, and nausea due to chemotherapy.[17] Alprazolam may also be indicated for the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder, as well as for the treatment of anxiety conditions with co-morbid depression.[2] The FDA label advises that the physician should periodically reassess the usefulness of the drug.[5]

Panic disorder

Alprazolam is effective in the relief of moderate to severe anxiety and panic attacks.[5] However, it is not a first line treatment since the development of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, and alprazolam is no longer recommended in Australia for the treatment of panic disorder due to concerns regarding tolerance, dependence, and abuse.[10] Most evidence shows that the benefits of alprazolam in treating panic disorder last only 4 to 10 weeks. However, people with panic disorder have been treated on an open basis for up to 8 months without apparent loss of benefit.[5][2]

In the United States, alprazolam is FDA-approved for the treatment of panic disorder with or without agoraphobia.[5] Alprazolam is recommended by the World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) for treatment-resistant cases of panic disorder where there is no history of tolerance or dependence.[19]

Anxiety disorders

Anxiety associated with depression is responsive to alprazolam. Clinical studies have shown that the effectiveness is limited to 4 months for anxiety disorders.[5] However, the research into antidepressant properties of alprazolam is poor and has only assessed its short-term effects against depression.[20] In one study, some long term, high-dosage users of alprazolam developed reversible depression.[21] In the US, alprazolam is FDA-approved for the management of anxiety disorders (a condition corresponding most closely to the APA Diagnostic and Statistical Manual DSM-IV-TR diagnosis of generalized anxiety disorder) or the short-term relief of symptoms of anxiety. In the UK, alprazolam is recommended for the short-term treatment (2–4 weeks) of severe acute anxiety.[2][22][23]

Nausea due to chemotherapy

Alprazolam may be used in combination with other medications for chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting.[17]

Pregnancy and lactation

Benzodiazepines cross the placenta, enter the fetus, and are also excreted in breast milk. Chronic administration of diazepam, another benzodiazepine, to nursing mothers has been reported to cause their infants to become lethargic and to lose weight.[24][25]

The use of alprazolam during pregnancy is associated with congenital abnormalities,[2][26] and use in the last trimester may cause fetal drug dependence and withdrawal symptoms in the post-natal period as well as neonatal flaccidity and respiratory problems.[27][28] However, in long-term users of benzodiazepines, abrupt discontinuation due to concerns of teratogenesis has a high risk of causing extreme withdrawal symptoms and a severe rebound effect of the underlying mental health disorder. Spontaneous abortions may also result from abrupt withdrawal of psychotropic medications, including benzodiazepines.[29]

Contraindications

Benzodiazepines require special precaution if used in children and in alcohol- or drug-dependent individuals. Particular care should be taken in pregnant or elderly people, people with substance abuse history (particularly alcohol dependence), and people with comorbid psychiatric disorders.[30] The use of alprazolam should be avoided or carefully monitored by medical professionals in individuals with: myasthenia gravis, acute narrow-angle glaucoma, severe liver deficiencies (e.g., cirrhosis), severe sleep apnea, pre-existing respiratory depression, marked neuromuscular respiratory, acute pulmonary insufficiency, chronic psychosis, hypersensitivity or allergy to alprazolam or other benzodiazepines, and borderline personality disorder (where it may induce suicidality and dyscontrol).[23][31][32]

Like all central nervous system depressants, alprazolam in larger-than-normal doses can cause significant deterioration in alertness and increase drowsiness, especially in those unaccustomed to the drug's effects.[33]

Elderly individuals should be cautious in the use of alprazolam due to the possibility of increased susceptibility to side-effects, especially loss of coordination and drowsiness.[24]

Adverse effects

Possible side effects include:

- Anterograde amnesia[34] and concentration problems

- Ataxia, slurred speech[35]

- Disinhibition[36]

- Drowsiness, dizziness, lightheadedness, fatigue, unsteadiness and impaired coordination, vertigo[37][38]

- Dry mouth (infrequent)[39]

- Hallucinations (rare)[40]

- Jaundice (very rare)[41]

- Skin rash, respiratory depression, constipation[37][38]

- Suicidal ideation or suicide[13]

- Urinary retention (infrequent)[42]

Paradoxical reactions

Although unusual, the following paradoxical reactions have been shown to occur:

- Aggression[43]

- Mania, agitation, hyperactivity, and restlessness[44][45][46]

- Rage, hostility[36]

- Twitches and tremor[47]

Food and drug interactions

Alprazolam is primarily metabolized via CYP3A4.[48] Combining CYP3A4 inhibitors such as cimetidine, erythromycin, norfluoxetine, fluvoxamine, itraconazole, ketoconazole, nefazodone, propoxyphene, and ritonavir delay the hepatic clearance of alprazolam, which may result in its accumulation[49] and increased severity of its side effects.[50][51]

Imipramine and desipramine have been reported to be increased an average of 31% and 20% respectively by the concomitant administration of alprazolam tablets.[52] Combined oral contraceptive pills reduce the clearance of alprazolam, which may lead to increased plasma levels of alprazolam and accumulation.[53]

Alcohol is one of the most common interactions; alcohol and alprazolam taken in combination have a synergistic effect on one another, which can cause severe sedation, behavioral changes, and intoxication. The more alcohol and alprazolam taken, the worse the interaction.[36] Combination of alprazolam with the herb kava can result in the development of a semi-comatose state.[54] Plants in the Hypericum genus (including St. John's wort) conversely can lower the plasma levels of alprazolam and reduce its therapeutic effect.[55][56][57]

Overdose

Overdoses of alprazolam can be mild to severe depending on how much of it taken and other drugs that have been taken.[58]

Alprazolam overdoses cause excess central nervous system (CNS) depression and may include one or more of the following symptoms:[42]

- Coma and death if alprazolam is combined with other substances.

- Fainting

- Hypotension (low blood pressure)

- Hypoventilation (shallow breathing)

- Impaired motor functions

- Dizziness

- Impaired balance

- Impaired or absent reflexes

- Muscle weakness

- Orthostatic hypotension (fainting while standing up too quickly)

- Somnolence (drowsiness)

Dependence and withdrawal

Alprazolam, like other benzodiazepines, binds to specific sites on the GABAA (gamma-amino-butyric acid) receptor. When bound to these sites, which are referred to as benzodiazepine receptors, it modulates the effect of GABAA receptors and, thus, of GABAergic neurons. Long-term use causes adaptive changes in the benzodiazepine receptors, making them less sensitive to stimulation and thus making the drugs less potent.[59]

Withdrawal and rebound symptoms commonly occur and necessitate a gradual reduction in dosage to minimize withdrawal effects when discontinuing.[8]

Not all withdrawal effects are evidence of true dependence or withdrawal. Recurrence of symptoms such as anxiety may simply indicate that the drug was having its expected anti-anxiety effect and that, in the absence of the drug, the symptom has returned to pretreatment levels. If the symptoms are more severe or frequent, the person may be experiencing a rebound effect due to the removal of the drug. Either of these can occur without the person actually being drug-dependent.[59]

Alprazolam and other benzodiazepines may also cause the development of physical dependence, tolerance, and benzodiazepine withdrawal symptoms during rapid dose reduction or cessation of therapy after long-term treatment.[60][61] There is a higher chance of withdrawal reactions if the drug is administered in a higher dosage than recommended, or if a person stops taking the medication altogether without slowly allowing the body to adjust to a lower-dosage regimen.[62][63]

In 1992, Romach and colleagues reported that dose escalation is not a characteristic of long-term alprazolam users, and that the majority of long-term alprazolam users change their initial pattern of regular use to one of symptom control only when required.[64]

Some common symptoms of alprazolam discontinuation include malaise, weakness, insomnia, tachycardia, lightheadedness, and dizziness.[65]

Those taking more than 4 mg per day have an increased potential for dependence. This medication may cause withdrawal symptoms upon abrupt withdrawal or rapid tapering, which in some cases have been known to cause seizures, as well as marked delirium similar to that produced by the anticholinergic tropane alkaloids of Datura (scopolamine and atropine).[66][67][68] The discontinuation of this medication may also cause a reaction called rebound anxiety.

In a 1983 study, only 5% of patients who had abruptly stopped taking long-acting benzodiazepines after less than 8 months demonstrated withdrawal symptoms, but 43% of those who had been taking them for more than 8 months did. With alprazolam – a short-acting benzodiazepine – taken for 8 weeks, 65% of patients experienced significant rebound anxiety. To some degree, these older benzodiazepines are self-tapering.[69]

The benzodiazepines diazepam (Valium) and oxazepam (Serepax) have been found to produce fewer withdrawal reactions than alprazolam (Xanax), temazepam (Restoril/Normison), or lorazepam (Temesta/Ativan). Factors that determine the risk of psychological dependence or physical dependence and the severity of the benzodiazepine withdrawal symptoms during dose reduction of alprazolam include: dosage used, length of use, frequency of dosing, personality characteristics of the individual, previous use of cross-dependent/cross-tolerant drugs (alcohol or other sedative-hypnotic drugs), current use of cross-dependent/-tolerant drugs, use of other short-acting, high-potency benzodiazepines,[70][71] and method of discontinuation.[62]

Detection in body fluids

Alprazolam may be quantified in blood or plasma to confirm a diagnosis of poisoning in hospitalized patients, provide evidence in an impaired driving arrest, or to assist in a medicolegal death investigation. Blood or plasma alprazolam concentrations are usually in a range of 10–100 μg/L in persons receiving the drug therapeutically, 100–300 μg/L in those arrested for impaired driving, and 300–2000 μg/L in victims of acute overdosage. Most commercial immunoassays for the benzodiazepine class of drugs will cross-react with alprazolam, but confirmation and quantitation is usually performed using chromatographic techniques.[72][73][74]

Pharmacology

Mechanism of action

Alprazolam is classed as a high-potency triazolobenzodiazepine:[75][76] a benzodiazepine with a triazole ring attached to its structure. As a benzodiazepine, alprazolam produces a variety of therapeutic and adverse effects by binding to the benzodiazepine receptor site on the GABAA receptor and modulating its function; GABA receptors are the most prolific inhibitory receptor within the brain. The GABA chemical and receptor system mediates inhibitory or calming effects of alprazolam on the nervous system. The GABAA receptor is made up of 5 subunits out of a possible 19, and GABAA receptors made up of different combinations of subunits have different properties, different locations within the brain, and, importantly, different activities with regard to benzodiazepines. Alprazolam and other triazolobenzodiazepines like triazolam that have a triazol ring attached to their structure appear to have antidepressant properties, since the structure resembles that of tricyclic antidepressants, which also have rings[34][77] Alprazolam causes a marked suppression of the hypothalamicpituitary-adrenal axis. The therapeutic properties of alprazolam are similar to other benzodiazepines and include anxiolytic, anticonvulsant, muscle relaxant, hypnotic[78] and amnesic; however, it is used mainly as an anxiolytic.[7]

Administration of alprazolam, as compared to lorazepam, has been demonstrated to elicit a statistically significant increase in extracellular dopamine D1 and D2 concentrations in the striatum.[79][80]

Pharmacokinetics

Alprazolam is taken orally, and is absorbed well – 80% of alprazolam binds to proteins in the serum (the majority binding to albumin). The concentration of alprazolam peaks after one to two hours.[2]

Alprazolam is metabolized in the liver, mostly by the enzyme cytochrome P450 3A4 (CYP3A4). Two major metabolites are produced: 4-hydroxyalprazolam and α-hydroxyalprazolam, as well as an inactive benzophenone. The low concentrations and low potencies of 4-hydroxyalprazolam and α-hydroxyalprazolam indicate that they have little to no contribution to the effects of alprazolam.[2]

The metabolites, as well as some unmetabolized alprazolam, are filtered out by the kidneys and are excreted in the urine.[2]

Forms of alprazolam

Alprazolam regular release and orally disintegrating tablets are available as 0.25 mg, 0.5 mg, 1 mg, and 2 mg tablets,[81] while extended release tablets are available as 0.5 mg, 1 mg, 2 mg, and 3 mg. Alprazolam oral solutions are available as 0.5 mg/5 mL and as 1 mg/1 mL oral solutions. Inactive ingredients in alprazolam tablets and solutions include microcrystalline cellulose, corn starch, docusate sodium, povidone, sodium starch glycollate, lactose monohydrate, magnesium stearate, colloidal silicon dioxide, and sodium benzoate. In addition, the 0.25 mg tablet contains D&C Yellow No. 10 and the 0.5 mg tablet contains FD&C Yellow No. 6 and D&C Yellow No. 10.[2]

Society and culture

Patent

Alprazolam is covered under U.S. Patent 3,987,052, which was filed on 29 October 1969, granted on 19 October 1976, and expired in September 1993.

Recreational use

There is a risk of misuse and dependence in both patients and non-medical users of alprazolam; alprazolam's high affinity binding, high potency, and rapid onset increase its abuse potential. The physical dependence and withdrawal syndrome of alprazolam also add to its addictive nature. In the small subgroup of individuals who escalate their doses there is usually a history of alcohol or other substance use disorders.[10] Despite this, most prescribed alprazolam users do not use their medication recreationally, and the long-term use of benzodiazepines does not generally correlate with the need for dose escalation.[82] However, based on US findings from the Treatment Episode Data Set (TEDS), an annual compilation of patient characteristics in substance abuse treatment facilities in the United States, admissions due to "primary tranquilizer" (including, but not limited to, benzodiazepine-type) drug use increased 79% from 1992 to 2002, suggesting that misuse of benzodiazepines may be on the rise.[83] In 2011, The New York Times reported, "The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention last year reported an 89 percent increase in emergency room visits nationwide related to nonmedical benzodiazepine use between 2004 and 2008."[84]

Alprazolam is one of the most commonly prescribed and misused benzodiazepines in the United States.[12][16] A large-scale nationwide U.S. government study conducted by SAMHSA found that, in the U.S., benzodiazepines are recreationally the most frequently used pharmaceuticals due to their widespread availability, accounting for 35% of all drug-related visits to hospital emergency and urgent care facilities. Men and women are equally likely to use benzodiazepines recreationally. The report found that alprazolam is the most common benzodiazepine for recreational use, followed by clonazepam, lorazepam, and diazepam. The number of emergency room visits due to benzodiazepines increased by 36% between 2004 and 2006.[16]

Regarding the significant increases detected, it is worthwhile to consider that the number of pharmaceuticals dispensed for legitimate therapeutic uses may be increasing over time, and DAWN estimates are not adjusted to take such increases into account. Nor do DAWN estimates take into account the increases in the population or in ED use between 2004 and 2006.[16]

At a particularly high risk for misuse and dependence are people with a history of alcoholism or drug abuse and/or dependence[85][86] and people with borderline personality disorder.[87]

Alprazolam, along with other benzodiazepines, is often used with other recreational drugs. These uses include aids to relieve the panic or distress of dysphoric ("bad trip") reactions to psychedelic drugs, such as LSD, and the drug-induced agitation and insomnia in the "comedown" stages of stimulant use, such as amphetamine, cocaine, and phencyclidine allowing sleep. Alprazolam may also be used with other depressant drugs, such as ethanol, heroin and other opioids, in an attempt to enhance their psychological effects. Alprazolam may be used in conjunction with cannabis, with users citing a synergistic effect achieved after consuming the combination.

The poly-drug use of powerful depressant drugs poses the highest level of health concerns due to a significant increase in the likelihood of experiencing an overdose which may result in fatal respiratory depression.[88][89]

A 1990 study claimed that diazepam has a higher misuse potential relative to other benzodiazepines, and that some data suggests that alprazolam and lorazepam resemble diazepam in this respect.[90]

Anecdotally injection of alprazolam has been reported, causing dangerous damage to blood vessels, closure of blood vessels (embolization) and decay of muscle tissue (rhabdomyolysis).[91] Alprazolam is not very soluble in water, and when crushed in water it will not fully dissolve (40 µg/ml of H2O at pH 7).[92] There have also been anecdotal reports of alprazolam being snorted.[93] Due to the low weight of a dose, alprazolam in one case was found to be distributed on blotter paper in a manner similar to LSD.[94]

Popular culture

Slang terms for alprazolam vary from place to place. Some of the more common terms are shortened versions of the trade name "Xanax", such as Xannies (or Xanies);[95][96] references to their drug classes, such as benzos or downers; or remark upon their shape or color (most commonly a straight, perforated tablet or an oval-shaped pill): bars, Xanbars, Z-bars, footballs, planks, poles, blues, or blue footballs.[97][98][99]

Availability

Alprazolam is available in English-speaking countries under the following brand names:[100]

- Alprax, Alprocontin, Alzam, Alzolam, Anzilum, Apo-Alpraz, Helex, Kalma, Mylan-Alprazolam, Niravam, Novo-Alprazol, Nu-Alpraz, Pacyl, Restyl, Tranax, Trika, Xycalm, Xanax, Xanor, Zolam, Zopax.

As of December 2013, in anticipation of the rescheduling of alprazolam to Schedule 8 in Australia—Pfizer Australia announced they would be discontinuing the Xanax brand in Australia as it is no longer commercially viable.[101]

Legal status

Alprazolam has varied legal status depending on jurisdiction:

- In the United States, alprazolam is a prescription drug and is assigned to Schedule IV of the Controlled Substances Act by the Drug Enforcement Administration.[102]

- Under the UK drug misuse classification system, benzodiazepines are class C drugs (Schedule 4).[103] Note that in the UK, alprazolam is not available on the NHS and can only be obtained on a private prescription.[104]

- In Ireland, alprazolam is a Schedule 4 medicine.[105]

- In Sweden, alprazolam is a prescription drug in List IV (Schedule 4) under the Narcotics Drugs Act (1968).[106]

- In the Netherlands, alprazolam is a List 2 substance of the Opium Law and is available for prescription.

- In Germany, alprazolam can be prescribed normally in doses up to 1 mg. Higher doses are scheduled as Anlage III drugs and require a special prescription form.

- In Australia, alprazolam was originally a Schedule 4 (Prescription Only) medication; however, as of February 2014, it has become a Schedule 8 medication, subjecting it to more rigorous prescribing requirements.[107]

Internationally, alprazolam is included under the United Nations Convention on Psychotropic Substances as Schedule IV.[108]

References

- ↑ Dickinson, B; Rush, PA; Radcliffe, AB (1990). "Alprazolam use and dependence. A retrospective analysis of 30 cases of withdrawal". Western Journal Of Medicine. 152: 604–8. PMC 1002418

. PMID 2349800.

. PMID 2349800. - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 "Xanax (Alprazolam)". RxList. First DataBank. July 2008.

- ↑ Goldberg, Raymond (2009). Drugs Across the Spectrum. Cengage Learning. p. 195. ISBN 9781111782009.

- 1 2 3 Work Group on Panic Disorder (January 2009). APA Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Panic Disorder (2nd ed.). doi:10.1176/appi.books.9780890423905.154688.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "FDA approved labeling for Xanax revision 08/23/2011" (PDF). Federal Drug Administration. 23 August 2011. p. 4. Retrieved 14 September 2011.

Anxiety Disorders – XANAX Tablets (alprazolam) are indicated for the management of anxiety disorder (a condition corresponding most closely to the APA Diagnostic and Statistical Manual [DSMIII-R] diagnosis of generalized anxiety disorder) or the short-term relief of symptoms of anxiety. Anxiety or tension associated with the stress of everyday life usually does not require treatment with an anxiolytic... Panic Disorder – XANAX is also indicated for the treatment of panic disorder, with or without agoraphobia... Demonstrations of the effectiveness of XANAX by systematic clinical study are limited to 4 months duration for anxiety disorder and 4 to 10 weeks duration for panic disorder; however, patients with panic disorder have been treated on an open basis without any apparent loss of benefit. The physician should periodically reassess the usefulness of the drug for the individual patient.

- ↑ "In Pictures: The Most Popular Prescription Drugs". Forbes. Retrieved 16 June 2015.

- 1 2 Mandrioli, R.; Mercolini, L.; Raggi, M. A. (2008). "Benzodiazepine Metabolism: An Analytical Perspective". Current Drug Metabolism. 9 (8): 827–844. PMID 18855614. doi:10.2174/138920008786049258.

- 1 2 3 Verster, J. C.; Volkerts, E. R. (2004). "Clinical Pharmacology, Clinical Efficacy, and Behavioral Toxicity of Alprazolam: A Review of the Literature". CNS Drug Reviews. 10 (1): 45–76. PMID 14978513. doi:10.1111/j.1527-3458.2004.tb00003.x.

- ↑ Tampi, R. R.; Muralee, S.; Weder, N. D.; Penland, H., eds. (2008). Comprehensive Review of Psychiatry. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer / Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Health. p. 226. ISBN 978-0-7817-7176-4.

- 1 2 3 4 Moylan, S.; Giorlando, F.; Nordfjærn, T.; Berk, M. (2012). "The Role of Alprazolam for the Treatment of Panic Disorder in Australia" (PDF). The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 46 (3): 212–224. PMID 22391278. doi:10.1177/0004867411432074.

- 1 2 Pavuluri, M. N.; Janicak, P. G.; Marder, S. R. (2010). Principles and Practice of Psychopharmacotherapy (5th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer Health / Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 535. ISBN 978-1-60547-565-3.

- 1 2 Galanter, M. (2008). The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Substance Abuse Treatment (4th ed.). American Psychiatric Publishing. p. 222. ISBN 978-1-58562-276-4. Retrieved 22 January 2014.

- 1 2 Dodds, Tyler J. (2 March 2017). "Prescribed Benzodiazepines and Suicide Risk: A Review of the Literature". The primary care companion for CNS disorders. 19 (2). ISSN 2155-7780. PMID 28257172. doi:10.4088/PCC.16r02037

.

. - ↑ Walker, S. (1996). A Dose of Sanity: Mind, Medicine, and Misdiagnosis. New York: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 64–65. ISBN 978-0-471-19262-6.

- ↑ Langreth, Robert; Herper, Matthew (11 May 2010). "In Pictures: The Most Popular Prescription Drugs". Forbes.

- 1 2 3 4 "Drug Abuse Warning Network, 2006: National Estimates of Drug-Related Emergency Department Visits" (PDF). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. 2006. Retrieved 13 February 2012.

- 1 2 3 "Alprazolam". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 15 May 2011. Retrieved 3 April 2011.

- ↑ "DEA Brief Benzodiazepines". Archived from the original on 12 March 2009. Retrieved 1 October 2011.

Given the millions of prescriptions written for benzodiazepines (about 100 million in 1999), relatively few individuals increase their dose on their own initiative or engage in drug-seeking behavior.

- ↑ Bandelow, B.; Zohar, J.; Hollander, E.; Kasper, S.; Möller, H. J.; WFSBP Task Force On Treatment Guidelines For Anxiety, O. C. P. S. D. (2002). "World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) Guidelines for the Pharmacological Treatment of Anxiety, Obsessive-Compulsive and Posttraumatic Stress Disorders". World Journal of Biological Psychiatry. 3 (4): 171–199. PMID 12516310. doi:10.3109/15622970209150621

.

. - ↑ van Marwijk, H.; Allick, G.; Wegman, F.; Bax, A.; Riphagen, I. I. (2012). van Marwijk, Harm, ed. "Alprazolam for depression" (PDF). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 7: CD007139. PMID 22786504. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007139.pub2.

- ↑ Lydiard, R. B.; Laraia, M. T.; Ballenger, J. C.; Howell, E. F. (May 1987). "Emergence of Depressive Symptoms in Patients Receiving Alprazolam for Panic Disorder". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 144 (5): 664–665. PMID 3578580. doi:10.1176/ajp.144.5.664.

- ↑ "Xanax". Netdoctor.co.uk. NetDoctor. 1 October 2006. Archived from the original on 9 August 2007. Retrieved 2 August 2007.

- 1 2 "Alprazolam". British National Formulary. 2007. Retrieved 3 August 2007.

- 1 2 "Alprazolam – Oral (Xanax) Side Effects, Medical Uses, and Drug Interactions". Medicinenet.com. MedicineNet. July 2005. Archived from the original on 18 December 2008. Retrieved 7 December 2008.

- ↑ "Xanax (Alprazolam) Drug Information: Uses, Side Effects, Drug Interactions and Warnings". RxList.com. RxList. July 2008. p. 8. Archived from the original on 13 September 2008. Retrieved 7 December 2008.

- ↑ Oo, C. Y.; Kuhn, R. J.; Desai, N.; Wright, C. E.; McNamara, P. J. (1995). "Pharmacokinetics in Lactating Women: Prediction of Alprazolam Transfer into Milk". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 40 (3): 231–236. PMC 1365102

. PMID 8527284. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.1995.tb05778.x.

. PMID 8527284. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.1995.tb05778.x. - ↑ Iqbal, M. M.; Sobhan, T.; Ryals, T. (2002). "Effects of Commonly Used Benzodiazepines on the Fetus, the Neonate, and the Nursing Infant" (PDF). Psychiatric Services. 53 (1): 39–49. PMID 11773648. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.53.1.39.

- ↑ García-Algar, Ó.; López-Vílchez, M. Á.; Martín, I.; Mur, A.; Pellegrini, M.; Pacifici, R.; Rossi, S.; Pichini, S. (2007). "Confirmation of Gestational Exposure to Alprazolam by Analysis of Biological Matrices in a Newborn with Neonatal Sepsis". Clinical Toxicology. 45 (3): 295–298. PMID 17453885. doi:10.1080/15563650601072191.

- ↑ Einarson, A.; Selby, P.; Koren, G. (2001). "Abrupt Discontinuation of Psychotropic Drugs During Pregnancy: Fear of Teratogenic Risk and Impact of Counselling". Journal of Psychiatry and Neuroscience. 26 (1): 44–48. PMC 1408034

. PMID 11212593.

. PMID 11212593. - ↑ Authier, N.; Balayssac, D.; Sautereau, M.; Zangarelli, A.; Courty, P.; Somogyi, A. A.; et al. (2009). "Benzodiazepine Dependence: Focus on Withdrawal Syndrome" (PDF). Annales Pharmaceutiques Françaises. 67 (6): 408–413. PMID 19900604. doi:10.1016/j.pharma.2009.07.001.

- ↑ Hori, A. (1998). "Pharmacotherapy for Personality Disorders". Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 52 (1): 13–19. PMID 9682928. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1819.1998.tb00967.x

.

. - ↑ Gardner, D. L.; Cowdry, R. W. (1985). "Alprazolam-Induced Dyscontrol in Borderline Personality Disorder". American Journal of Psychiatry. 142 (1): 98–100. PMID 2857071. doi:10.1176/ajp.142.1.98.

- ↑ Kozená, L.; Frantik, E.; Horváth, M. (1995). "Vigilance Impairment after a Single Dose of Benzodiazepines". Psychopharmacology. 119 (1): 39–45. PMID 7675948. doi:10.1007/BF02246052.

- 1 2 Barbee, J. G. (1993). "Memory, Benzodiazepines, and Anxiety: Integration of Theoretical and Clinical Perspectives". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 54 (Suppl): 86–97; discussion 98–101. PMID 8262893.

- ↑ Cassano, G. B.; Toni, C.; Petracca, A.; Deltito, J.; Benkert, O.; Curtis, G.; et al. (1994). "Adverse Effects Associated with the Short-term Treatment of Panic Disorder with Imipramine, Alprazolam or Placebo" (PDF). European Neuropsychopharmacology. 4 (1): 47–53. PMID 8204996. doi:10.1016/0924-977X(94)90314-X.

- 1 2 3 Michel, L.; Lang, J. P. (2003). "Benzodiazépines et passage à l'acte criminel" [Benzodiazepines and Forensic Aspects] (PDF). Encephale (in French). 29 (6): 479–485. PMID 15029082. Retrieved 9 April 2013.

- 1 2 Rawson, N. S.; Rawson, M. J. (1999). "Acute Adverse Event Signalling Scheme Using the Saskatchewan Administrative Health Care Utilization Datafiles: Results for Two Benzodiazepines". Canadian Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 6 (3): 159–166. PMID 10495368.

- 1 2 "Alprazolam – Complete Medical Information Regarding This Treatment of Anxiety Disorders". Medicinenet.com. MedicineNet. Retrieved 2 August 2007.

- ↑ Elie, R.; Lamontagne, Y. (1984). "Alprazolam and Diazepam in the Treatment of Generalized Anxiety". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 4 (3): 125–129. PMID 6145726. doi:10.1097/00004714-198406000-00002.

- ↑ "Complete Alprazolam Information". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 5 August 2007. Retrieved 2 August 2007.

- ↑ Noyes, R.; DuPont, R. L.; Pecknold, J. C.; Rifkin, A.; Rubin, R. T.; Swinson, R. P.; et al. (1988). "Alprazolam in Panic Disorder and Agoraphobia: Results from a Multicenter Trial. II. Patient Acceptance, Side Effects, and Safety". Archives of General Psychiatry. 45 (5): 423–428. PMID 3358644. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1988.01800290037005.

- 1 2 "Alprazolam Side Effects, Interactions and Information". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 19 August 2007. Retrieved 2 August 2007.

- ↑ Rapaport, M.; Braff, D. L. (1985). "Alprazolam and Hostility". American Journal of Psychiatry. 142 (1): 146. PMID 2857070.

- ↑ Arana, G. W.; Pearlman, C.; Shader, R. I. (1985). "Alprazolam-Induced Mania: Two Clinical Cases". American Journal of Psychiatry. 142 (3): 368–369. PMID 2857534. doi:10.1176/ajp.142.3.368.

- ↑ Strahan, A.; Rosenthal, J.; Kaswan, M.; Winston, A. (1985). "Three Case Reports of Acute Paroxysmal Excitement Associated with Alprazolam Treatment". American Journal of Psychiatry. 142 (7): 859–861. PMID 2861755. doi:10.1176/ajp.142.7.859.

- ↑ Reddy, J.; Khanna, S.; Anand, U.; Banerjee, A. (1996). "Alprazolam-Induced Hypomania". Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 30 (4): 550–552. PMID 8887708. doi:10.3109/00048679609065031.

- ↑ Béchir, M.; Schwegler, K.; Chenevard, R.; Binggeli, C.; Caduff, C.; Büchi, S.; et al. (2007). "Anxiolytic Therapy with Alprazolam Increases Muscle Sympathetic Activity in Patients with Panic Disorders" (PDF). Autonomic Neuroscience. 134 (1–2): 69–73. PMID 17363337. doi:10.1016/j.autneu.2007.01.007.

- ↑ Otani, K. (2003). "Cytochrome P450 3A4 and Benzodiazepines". Seishin Shinkeigaku Zasshi (in Japanese). 105 (5): 631–642. PMID 12875231.

- ↑ Dresser, G. K.; Spence, J. D.; Bailey, D. G. (2000). "Pharmacokinetic-Pharmacodynamic Consequences and Clinical Relevance of Cytochrome P450 3A4 Inhibition". Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 38 (1): 41–57. PMID 10668858. doi:10.2165/00003088-200038010-00003.

- ↑ Greenblatt, D. J.; Wright, C. E. (1993). "Clinical Pharmacokinetics of Alprazolam. Therapeutic Implications". Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 24 (6): 453–471. PMID 8513649. doi:10.2165/00003088-199324060-00003.

- ↑ Wang, J. S.; Chase, C. L. (2003). "Pharmacokinetics and Drug Interactions of the Sedative Hypnotics" (PDF). Psychopharmacological Bulletin. 37 (1): 10–29. PMID 14561946. doi:10.1007/BF01990373. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 July 2007.

- ↑ "FDA SPL Approved Application Filing for NDC Code 0228-3083 (Alprazolam by Actavis Elizabeth LLC)".

- ↑ Back, D. J.; Orme, M. L. (1990). "Pharmacokinetic Drug Interactions with Oral Contraceptives". Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 18 (6): 472–484. PMID 2191822. doi:10.2165/00003088-199018060-00004.

- ↑ Izzo, A. A.; Ernst, E. (2001). "Interactions between Herbal Medicines and Prescribed Drugs: A Systematic Review" (PDF). Drugs. 61 (15): 2163–2175. PMID 11772128. doi:10.2165/00003495-200161150-00002.

- ↑ Izzo, A. A. (2004). "Drug Interactions with St. John's Wort (Hypericum perforatum): A Review of the Clinical Evidence". International Journal of Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 42 (3): 139–148. PMID 15049433. doi:10.5414/CPP42139.

- ↑ Madabushi, R.; Frank, B.; Drewelow, B.; Derendorf, H.; Butterweck, V. (2006). "Hyperforin in St. John's Wort Drug Interactions". European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 62 (3): 225–233. PMID 16477470. doi:10.1007/s00228-006-0096-0.

- ↑ Izzo, A. A.; Ernst, E. (2009). "Interactions between Herbal Medicines and Prescribed Drugs: An Updated Systematic Review". Drugs. 69 (13): 1777–1798. PMID 19719333. doi:10.2165/11317010-000000000-00000.

- ↑ Isbister, G. K.; O'Regan, L.; Sibbritt, D.; Whyte, I. M. (2004). "Alprazolam is Relatively more Toxic than other Benzodiazepines in Overdose". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 58 (1): 88–95. PMC 1884537

. PMID 15206998. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.2004.02089.x

. PMID 15206998. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.2004.02089.x  .

. - 1 2 Stahl, S. (1996). Essential Pharmacology: Neuroscientific Basis and Practical Applications. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-42620-0.

- ↑ Juergens, S. M.; Morse, R. M. (1988). "Alprazolam Dependence in seven Patients". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 145 (5): 625–627. PMID 3258735. doi:10.1176/ajp.145.5.625.

- ↑ Klein, E. (2002). "The Role of Extended-Release Benzodiazepines in the Treatment of Anxiety: A Risk-Benefit Evaluation with a Focus on Extended-Release Alprazolam"

. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 63 (Suppl 14): 27–33. PMID 12562116.

. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 63 (Suppl 14): 27–33. PMID 12562116. - 1 2 Ashton, Heather (August 2002). "The Ashton Manual – Benzodiazepines: How They Work and How to Withdraw". Benzo.org.uk. Retrieved 31 October 2008.

- ↑ Closser, M. H.; Brower, K. J. (1994). "Treatment of Alprazolam Withdrawal with Chlordiazepoxide Substitution and Taper" (PDF). Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 11 (4): 319–323. PMID 7966502. doi:10.1016/0740-5472(94)90042-6.

- ↑ Romach, M. K.; Somer, G. R.; Sobell, L. C.; Sobell, M. B.; Kaplan, H. L.; Sellers, E. M. (1992). "Characteristics of Long-Term Alprazolam Users in the Community" (PDF). Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 12 (5): 316–321. PMID 1479048. doi:10.1097/00004714-199210000-00004.

- ↑ Fyer, A. J.; Liebowitz, M. R.; Gorman, J. M.; Campeas, R.; Levin, A.; Davies, S. O.; et al. (1987). "Discontinuation of Alprazolam Treatment in Panic Patients". American Journal of Psychiatry. 144 (3): 303–308. PMID 3826428. doi:10.1176/ajp.144.3.303. Retrieved 10 December 2008.

- ↑ Breier, A.; Charney, D. S.; Nelson, J. C. (1984). "Seizures Induced by Abrupt Discontinuation of Alprazolam". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 141 (12): 1606–1607. PMID 6150649. doi:10.1176/ajp.141.12.1606.

- ↑ Noyes Jr, R.; Perry, P. J.; Crowe, R. R.; Coryell, W. H.; Clancy, J.; Yamada, T.; Gabel, J. (1986). "Seizures following the withdrawal of alprazolam". The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 174 (1): 50–52. PMID 2867122. doi:10.1097/00005053-198601000-00009.

- ↑ Levy, A. B. (1984). "Delirium and Seizures due to Abrupt Alprazolam Withdrawal: Case Report". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 45 (1): 38–39. PMID 6141159.

- ↑ Schatzberg, A.; DeBattista, C. (2003). Manual of Clinical Psychopharmacology. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Pub. p. 391. ISBN 1-58562-209-5. Retrieved 22 January 2014.

- ↑ Wolf, B.; Griffiths, R. R. (1991). "Physical Dependence on Benzodiazepines: Differences Within the Class". Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 29 (2): 153–156. PMID 1686752. doi:10.1016/0376-8716(91)90044-Y.

- ↑ Higgitt, A.; Fonagy, P.; Lader, M. (1988). "The Natural History of Tolerance to the Benzodiazepines". Psychological Medicine. Monograph Supplement. 13: 1–55. PMID 2908516. doi:10.1017/S0264180100000412.

- ↑ Jones, A. W.; Holmgren, A.; Kugelberg, F. C. (2007). "Concentrations of Scheduled Prescription Drugs in Blood of Impaired Drivers: Considerations for Interpreting the Results" (PDF). Therapeutic Drug Monitoring. 29 (2): 248–260. PMID 17417081. doi:10.1097/FTD.0b013e31803d3c04.

- ↑ Fraser, A. D.; Bryan, W. (1991). "Evaluation of the Abbott ADx and TDx Serum Benzodiazepine Immunoassays for Analysis of Alprazolam" (PDF). Journal of Analytic Toxicology. 15 (2): 63–65. PMID 1675703. doi:10.1093/jat/15.2.63.

- ↑ Baselt, R. (2011). Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man (9th ed.). Seal Beach, CA: Biomedical Publications. pp. 45–48. ISBN 978-0-9626523-8-7.

- ↑ Skelton, K. H.; Nemeroff, C. B.; Owens, M. J. (2004). "Spontaneous Withdrawal from the Triazolobenzodiazepine Alprazolam Increases Cortical Corticotropin-Releasing Factor mRNA Expression". Journal of Neuroscience. 24 (42): 9303–9312. PMID 15496666. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1737-04.2004

.

. - ↑ Chouinard, G. (2004). "Issues in the Clinical Use of Benzodiazepines: Potency, Withdrawal, and Rebound"

. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 65 (Suppl 5): 7–12. PMID 15078112.

. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 65 (Suppl 5): 7–12. PMID 15078112. - ↑ White, G.; Gurley, D. A. (1995). "α Subunits Influence Zn Block of γ2 Containing GABAA Receptor Currents". NeuroReport. 6 (3): 461–464. PMID 7766843. doi:10.1097/00001756-199502000-00014.

- ↑ Arvat, E.; Giordano, R.; Grottoli, S.; Ghigo, E. (2002). "Benzodiazepines and Anterior Pituitary Function". Journal of Endocrinological Investigation. 25 (8): 735–747. PMID 12240908. doi:10.1007/bf03345110.

- ↑ Bentué-Ferrer, D.; Reymann, J. M.; Tribut, O.; Allain, H.; Vasar, E.; Bourin, M. (2001). "Role of dopaminergic and serotonergic systems on behavioral stimulatory effects of low-dose alprazolam and lorazepam". European Neuropsychopharmacology. 11 (1): 41–50. PMID 11226811. doi:10.1016/S0924-977X(00)00137-1.

- ↑ Giardino, L.; Zanni, M.; Pozza, M.; Bettelli, C.; Covelli, V. (5 March 1998). "Dopamine receptors in the striatum of rats exposed to repeated restraint stress and alprazolam treatment". European Journal of Pharmacology. 344 (2-3): 143–147. ISSN 0014-2999. PMID 9600648. doi:10.1016/s0014-2999(97)01608-7.

- ↑ "Alprazolam Dosage, Uses, Overdose Info and More". RXwiki.com. 18 November 2013. Retrieved 22 January 2014. (

Page will play audio when loaded)

Page will play audio when loaded)

- ↑ Soumerai, S. B.; Simoni-Wastila, L.; Singer, C.; Mah, C.; Gao, X.; Salzman, C.; et al. (2003). "Lack of Relationship between Long-Term Use of Benzodiazepines and Escalation to High Dosages". Psychiatric Services. 54 (7): 1006–1011. PMID 12851438. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.54.7.1006

.

. - ↑ Licata, S. C.; Rowlett, J. K. (2008). "Abuse and Dependence Liability of Benzodiazepine-Type Drugs: GABAA Receptor Modulation and Beyond". Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 90 (1): 74–89. PMC 2453238

. PMID 18295321. doi:10.1016/j.pbb.2008.01.001.

. PMID 18295321. doi:10.1016/j.pbb.2008.01.001. - ↑ Goodnough, Abby (14 September 2011). "Abuse of Xanax Leads a Clinic to Halt Supply". New York Times.

- ↑ Ballenger, J. C. (1984). "Psychopharmacology of the Anxiety Disorders". The Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 7 (4): 757–771. PMID 6151647.

- ↑ Ciraulo, D. A.; Barnhill, J. G.; Greenblatt, D. J.; Shader, R. I.; Ciraulo, A. M.; Tarmey, M. F.; Molloy, M. A.; Foti, M. E. (1988). "Abuse Liability and Clinical Pharmacokinetics of Alprazolam in Alcoholic Men". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 49 (9): 333–337. PMID 3417618.

- ↑ Vorma, H.; Naukkarinen, H. H.; Sarna, S. J.; Kuoppasalmi, K. I. (2005). "Predictors of Benzodiazepine Discontinuation in Subjects Manifesting Complicated Dependence". Substance Use & Misuse. 40 (4): 499–510. PMID 15830732. doi:10.1081/JA-200052433.

- ↑ Walker, B. M.; Ettenberg, A. (2003). "The Effects of Alprazolam on Conditioned Place Preferences Produced by Intravenous Heroin". Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 75 (1): 75–80. PMID 12759115. doi:10.1016/S0091-3057(03)00043-1.

- ↑ "OSAM-O-GRAM Highlights of Statewide Drug Use Trends" (PDF). Ohio, US: Wright State University and the University of Akron. January 2008. Retrieved 10 December 2008.

- ↑ Griffiths, R. R.; Wolf, B. (1990). "Relative Abuse Liability of Different Benzodiazepines in Drug Abusers". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 10 (4): 237–243. PMID 1981067. doi:10.1097/00004714-199008000-00002.

- ↑ Wang, E. C.; Chew, F. S. (2006). "MR Findings of Alprazolam Injection into the Femoral Artery with Microembolization and Rhabdomyolysis". Radiology Case Reports. 1 (3). doi:10.2484/rcr.v1i3.33

.

. - ↑ "DB00404 (Alprazolam)". Canada: DrugBank. 26 June 2008. Archived from the original on 29 January 2008. Retrieved 12 July 2011.

- ↑ Sheehan, M. F.; Sheehan, D. V.; Torres, A.; Coppola, A.; Francis, E. (1991). "Snorting benzodiazepines". The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 17 (4): 457–468. PMID 1684083. doi:10.3109/00952999109001605.

- ↑ "Intelligence Alert – Xanax Blotter Paper in Bartlesville, Oklahoma" (Microgram Bulletin). US Drug Enforcement Administration. May 2008. Archived from the original on 21 May 2008.

- ↑ Mesibov, Ginnie (2004). Outer Strength, Inner Strength. Xulon Press. p. 213. ISBN 9781594675041.

Some people sell Xanax on the street for ten or fifteen dollars a pill. They call them Xannies.

- ↑ Curry, Mark (2009). Dancing with the Devil: How Puff Burned the Bad Boys of Hip-hop. NewMark Books. p. 120. ISBN 9780615276502.

Puff would get so wired sometimes – his favorites were weed, ecstasy and xannies (Xanax) – that he wouldn't realize that he was speeding.

- ↑ "Street Terms for Xanax". Axisresidentialtreatment.com. Archived from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 14 February 2014.

- ↑ "Street Names for Alprazolam". Alprazolamaddictionhelp.com. Retrieved 14 February 2014.

- ↑ "Xanax Effects and Withdrawal Symptoms". Drugrehabtreatmenthelp.com. 2010. Retrieved 14 February 2014.

- ↑ "Benzodiazepine Names". Non-benzodiazepines.org.uk. Archived from the original on 8 December 2008. Retrieved 31 October 2008.

- ↑ "Discontinuation of Xanax" (PDF). Pfizer Australia.

- ↑ "DEA, Drug Scheduling". DEA. Archived from the original on 4 November 2008. Retrieved 31 October 2008.

- ↑ "Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 (c. 38)". The UK Statute Law database. 1991.

- ↑ British Medical Association, Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain (September 2010). "4.1.2: Anxiolytics". British National Formulary (BNF 60). United Kingdom: BMJ Group and RPS Publishing. p. 212. ISBN 978-0-85369-931-6.

- ↑ "Misuse Of Drugs (Amendment) Regulations". Irish Statute Book. Office of the Attorney General. 1993.

- ↑ "Läkemedelsverkets föreskrifter (LVFS 2011:10) om förteckningar över narkotika" [Medical Products Agency on the lists of drugs] (PDF) (in Swedish). Sweden: Läkemedelsverket. October 2011.

- ↑ "Alprazolam to be rescheduled from next year". 2013. (Subscription required (help)).

- ↑ "List of Psychotropic Substances under International Control" (PDF). Incb.org. International Narcotics Control Board. August 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 December 2008. Retrieved 7 December 2008.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Alprazolam. |

- U.S. National Library of Medicine: Drug Information Portal – Alprazolam

- Erowid Alprazolam (Xanax) Vault