James Parkinson

| James Parkinson | |

|---|---|

| Born |

11 April 1755 Shoreditch, London, England |

| Died |

21 December 1824 (aged 69) Shoreditch, London, England |

| Cause of death | Stroke |

| Nationality | British |

| Occupation | Surgeon |

| Known for | First description of Parkinson's disease |

| Spouse(s) | Mary Dale |

| Children | 6[1] |

James Parkinson FGS (11 April 1755 – 21 December 1824)[2] was an English surgeon, apothecary, geologist, palaeontologist, and political activist. He is most famous for his 1817 work, An Essay on the Shaking Palsy[3] in which he was the first to describe "paralysis agitans", a condition that would later be renamed Parkinson's disease by Jean-Martin Charcot.

Early life

James Parkinson was born in Shoreditch, London, England. He was the son of John Parkinson, an apothecary and surgeon practising in Hoxton Square in London.[4] He was the oldest of three siblings, which included his brother William and his sister Mary Sedgewood.[1] In 1784 Parkinson was approved by the City of London Corporation as a surgeon.

On 21 May 1783, he married Mary Dale, with whom he subsequently had eight children; two did not survive past childhood. Soon after he was married, Parkinson succeeded his father in his practice in 1 Hoxton Square. He believed that any worthwhile surgeon should know shorthand, at which he was adept.

Politics

In addition to his flourishing medical practice, Parkinson had an avid interest in geology and palaeontology, as well as the politics of the day.[5]

Parkinson was a strong advocate for the under-privileged, and an outspoken critic of the Pitt government. His early career was marred by his being involved in a variety of social and revolutionary causes, and some historians think it most likely that he was a strong proponent for the French Revolution. He published nearly twenty political pamphlets in the post-French Revolution period, while Britain was in political chaos. Writing under his own name and his pseudonym "Old Hubert", he called for radical social reforms and universal suffrage.[6]

Parkinson called for representation of the people in the House of Commons, the institution of annual parliaments, and universal suffrage. He was a member of several secret political societies, including the London Corresponding Society and the Society of Constitutional Information.[1] In 1794 his membership in the organisation led to his being examined under oath before William Pitt and the Privy Council to give evidence about a trumped-up plot to assassinate King George III. He refused to testify regarding his part in the popgun plot, until he was certain he would not be forced to incriminate himself. The plan was to use a poisoned dart fired from a pop-gun to bring the king's reign to a premature conclusion. No charges were ever brought against Parkinson but several of his friends languished in prison for many months before being acquitted.

Medicine

.png)

Parkinson turned away from his tumultuous political career, and between 1799 and 1807 published several medical works, including a work on gout in 1805.[7] He was also responsible for early writings on ruptured appendix in English medical literature.

Parkinson was also interested in improving the general health and well-being of the population. He wrote several medical doctrines that exposed a similar zeal for the health and welfare of the people that was expressed by his political activism. He was a crusader for legal protection for the mentally ill, as well as their doctors and families.

In 1812 Parkinson assisted his son with the first described case of appendicitis in English, and the first instance in which perforation was shown to be the cause of death.

Parkinson's disease

Parkinson was the first person to systematically describe six individuals with symptoms of the disease that bears his name. In his "An Essay on the Shaking Palsy", he reported on three of his own patients and three persons who he saw in the street.[8] He referred to the disease that would later bear his name as paralysis agitans, or shaking palsy.[9] He distinguished between resting tremors and the tremors with motion.[10] Jean-Martin Charcot coined the term "Parkinson's disease" some 60 years later.

Parkinson erroneously predicted that the tremors in these patients were due to lesions in the cervical spinal cord.[11]

Science

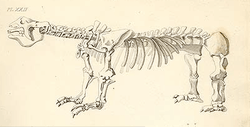

Parkinson's interest gradually turned from medicine to nature, specifically the relatively new field of geology, and palaeontology. He began collecting specimens and drawings of fossils in the latter part of the eighteenth century. He took his children and friends on excursions to collect and observe fossil plants and animals. His attempts to learn more about fossil identification and interpretation were frustrated by a lack of available literature in English, and so he took the decision to improve matters by writing his own introduction to the study of fossils.

In 1804, the first volume of his Organic Remains of a Former World was published.[12] Gideon Mantell praised it as "the first attempt to give a familiar and scientific account of fossils". A second volume was published in 1808, and a third in 1811. Parkinson illustrated each volume and his daughter Emma coloured some of the plates. The plates were later re-used by Gideon Mantell. In 1822 Parkinson published the shorter "Outlines of Oryctology: an Introduction to the Study of Fossil Organic Remains, especially of those found in British Strata".

Parkinson also contributed several papers to William Nicholson's "A Journal of Natural Philosophy, Chemistry and the Arts", and in the first, second, and fifth volumes of the "Geological Society's Transactions". He wrote a single volume 'Outlines of Orytology' in 1822, a more popularise work.

On 13 November 1807, Parkinson and other distinguished gentlemen met at the Freemasons' Tavern in London. The gathering included such great names as Sir Humphry Davy, Arthur Aikin and George Bellas Greenough. This was to be the first meeting of the Geological Society of London.[13]

Parkinson belonged to a school of thought, Catastrophism, that concerned itself with the belief that the Earth's geology and biosphere were shaped by recent large-scale cataclysms. He cited the Noachian deluge of Genesis as an example, and he firmly believed that creation and extinction were processes guided by the hand of God. His view on Creation was that each 'day' was actually a much longer period, that lasted perhaps tens of thousands of years in length.

Death and memorials

He died on 21 December 1824 after a stroke that interfered with his speech, bequeathing his houses in Langthorne to his sons and wife and his apothecary's shop to his son, John. His collection of organic remains was given to his wife and much of it went on to be sold in 1827, a catalogue of the sale has never been found. He was buried at St. Leonard's Church, Shoreditch.[14]

Parkinson's life is commemorated with a stone tablet inside the church of St Leonard's, Shoreditch, where he was a member of the congregation; the exact site of his grave is not known and his body may lie in the crypt or in the churchyard. In addition, a blue plaque at 1 Hoxton Square, marks the site of his home. Several fossils were also named after him. There is no known portrait of him: a photograph, sometimes published and identified as of him, is of a dentist of the same name, but this James Parkinson died before photography was invented.[15]

World Parkinson's Day is held each year on his birthday, 11 April.[16]

Works

- The Town and Country Friend and Physician (Philadelphia, 1803)

References

- 1 2 3 Dr. Stewart Factor DO; Dr. William Weiner MD; Dr. Stewart Factor (15 December 2007). Parkinson's Disease: Diagnosis & Clinical Management : Second Edition. Demos Medical Publishing. p. 35. ISBN 978-1-934559-87-1.

- ↑ Lewis, Cherry; Knell, Simon J. (2009). The making of the Geological Society of London. Geological Society. pp. 62 & 83. ISBN 978-1-86239-277-9.

- ↑ An Essay on the Shaking Palsy

- ↑ Ronald F. Pfeiffer; Zbigniew K. Wszolek; Manuchair Ebadi (9 October 2012). Parkinson's Disease, Second Edition. CRC Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-1-4398-0714-9.

- ↑ Yahr, MD (April 1978). "A physician for all seasons. James Parkinson 1755–1824". Archives of neurology. 35 (4): 185–8. ISSN 0003-9942. PMID 346008. doi:10.1001/archneur.1978.00500280003001.

- ↑ Jeremy R. Playfer; John V. Hindle (1 January 2008). Parkinson's Disease in the Older Patient. Radcliffe Publishing. p. 5. ISBN 978-1-84619-114-5.

- ↑ Jefferson, M (June 1973). "James Parkinson, 1775–1824". British Medical Journal. 2 (5866): 601–3. ISSN 0007-1447. PMC 1592166

. PMID 4576771. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.5866.601.

. PMID 4576771. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.5866.601. - ↑ McCall, Bridget (January 2003). "Dr. James Parkinson 1755–1824" (PDF). Parkinson's Diseas Society. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 February 2006. Retrieved 10 September 2009.

- ↑ Naheed Ali (26 September 2013). Understanding Parkinson's Disease: An Introduction for Patients and Caregivers. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. pp. 4–. ISBN 978-1-4422-2104-8.

- ↑ Currier, RD (April 1996). "Did John Hunter give James Parkinson an idea?". Archives of neurology. 53 (4): 377–8. ISSN 0003-9942. PMID 8929162. doi:10.1001/archneur.1996.00550040117022.

- ↑ Robert H. Wilkins; Irwin A. Brody (1997). Neurological Classics. Thieme. p. 87. ISBN 978-1-879284-49-4.

- ↑ James Parkinson (1833). Organic Remains of a Former World: The fossil zoophytes. M.A. Nattali.

- ↑ History of the Geological Society, UK.

- ↑ Lewis, Cherry; Knell, Simon J. (2009). The making of the Geological Society of London. Geological Society. p. 83. ISBN 978-1-86239-277-9.

- ↑ Gardner-Thorpe, Christopher. James Parkinson (1755–1824). Exeter.

- ↑ http://www.parkinsons.co.za/breaking-news/17-world-parkinsons-day

Further reading

- Morris, AD (April 1955). "James Parkinson, born April 11, 1755". Lancet. 268 (6867): 761–3. ISSN 0140-6736. PMID 14368866. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(55)90558-4.

- Eyles, JM (September 1955). "James Parkinson; 1755–1824". Nature. 176 (4482): 580–1. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 13265780. doi:10.1038/176580a0.

- Mchenry Lc, Jr (September 1958). "Surgeon and palaeontologist, James Parkinson". The Journal of the Oklahoma State Medical Association. 51 (9): 521–3. ISSN 0030-1876. PMID 13576252.

- Nelson, JN (October 1958). "James Parkinson". The New England Journal of Medicine. 259 (14): 686–7. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 13590427. doi:10.1056/NEJM195810022591408.

- "James Parkinson". Medical science. 15: 95. January 1964. PMID 14103628.

- Mulhearn, RJ (May 1971). "The history of James Parkinson and his disease". Australian and New Zealand journal of medicine. 1: Suppl 1:1–6. ISSN 0004-8291. PMID 4949271. doi:10.1111/j.1445-5994.1971.tb02558.x.

- Brian, VA (August 1976). "The man behind the name: James Parkinson, 1755–1824". Nursing times. 72 (31): 1201. ISSN 0954-7762. PMID 785393.

- Tyler, KL; Tyler, HR (February 1986). "The secret life of James Parkinson (1755–1824): the writings of Old Hubert". Neurology. 36 (2): 222–4. ISSN 0028-3878. PMID 3511403. doi:10.1212/wnl.36.2.222.

- Herzberg, L (1987). "Dr James Parkinson". Clinical and experimental neurology. 24: 221–3. ISSN 0196-6383. PMID 3077340.

- Sakula, A (February 2000). "James parkinson (1755–1824)". Journal of medical biography. 8 (1): 59. ISSN 0967-7720. PMID 10994050.

External links

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Parkinson, James. |

-

Works written by or about James Parkinson at Wikisource

Works written by or about James Parkinson at Wikisource - Information sheet about James Parkinson published by Parkinson's UK.

- Biography of James Parkinson from Who Named It?

- Works by James Parkinson at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about James Parkinson at Internet Archive

- A text reprinted version of An Essay on the Shaking Palsy with original spelling

- European Parkinson's Disease Association