Women in the Ottoman Empire

This article looks at several examples of women's issues in Ottoman society.

Women in Ottoman Law

Islamic women in the Ottoman Empire were governed by the Sharia. Sharia deals with many topics addressed by secular law, including crime, politics, and economics, as well as personal matters such as sexual intercourse, hygiene, diet, prayer, everyday etiquette and fasting.

There are two primary sources of sharia law: the precepts set forth in the Quranic verses (ayahs), and the example set by the Islamic prophet Muhammad in the Sunnah.[1] Where it has official status, sharia is interpreted by Islamic judges (qadis) with varying responsibilities for the religious leaders (imams). For questions not directly addressed in the primary sources, the application of sharia is extended through consensus of the religious scholars (ulama) thought to embody the consensus of the Muslim Community (ijma).

The muftis play an important role in this decision-making process, because as learned scholars, their opinions about a certain case were recorded and could affect the judge's decision. A judge or any other individual could request the muftis' help in legal matters. Depending on the standing of a mufti, his fatwa could overrule the judge's decision in certain cases.

Lay women possessed a great deal of agency for the time period. Ottoman women, for example, could own property, and retained their property after marriage. They also had access to the justice system and could access a judge, as well as be taken to court themselves. By comparison, many married European women did not have this right, nor could they own property until the nineteenth or twentieth centuries. Despite these advantages, the law limited women’s abilities to testify for themselves, which kept them at a disadvantage. Because women had access to the legal system, much of the information about women in Ottoman society comes from court records.[2] Muslim women in the early modern empire “bought and sold property, inherited and bequeathed wealth, established waqfs [endowments], borrowed and lent money, and at times even served as holders of timar [prebends] and usufruct rights on miri [state] land, as tax farmers and in business partnerships.” Because of their leverage in shari’ah courts, and the importance of these courts in the empire, non-Muslim women often saw conversion as a way to attain greater autonomy.[3]

Ottoman society kept women under control as concubines or through marriage. Marriages, which were usually arranged by parents, could occasionally be escaped by men, but women rarely did the same. It was rare for anyone, of either gender, to remain unmarried.[4] In a survey taken in the twentieth century, only two percent of women did not marry before the end of their childbearing years, and 1885 and 1907 surveys found 8 and 5 percent of men, respectively, unmarried by their mid-fifties.[5] Muslim men could take non-Muslim wives, and his descendents would be considered Muslim, but non-Muslim men could not marry Muslim wives.[6] Polygamy was relatively uncommon, only being found in palace society and religious officials, and monogamy was the norm. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, princesses acquired stronger influence in high society, and as a result, many high-class women began to demand monogamy and frown upon polygamy, with limited success.[4]

Divorces were fairly frequent and could be initiated by either party. However, men did not have to provide a reason and could expect to be compensated and to compensate his wife, whereas women had to provide a reason, such as “there is a lack of good understanding between us.” Upon divorce, women would lose any financial benefit brought to her by the marriage and would sometimes have to pay her husband.[4]

Social Life

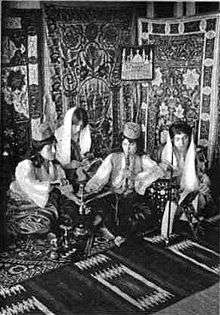

Women socialized with one another in their homes and at bathhouses. High society women, particularly those who did not live in the palace, visited one another for long periods of time at each other’s homes. Those who lived in the palace were subject to strict etiquette that prevented easy socializing. Townswomen visited one another at home and also at the baths, which were an important social ritual. Women would bring their finest bathing accessories, such as embroidered towels and high, wooden sandals.[7]

Education

The Tanzimat reforms of the nineteenth century brought additional rights to women, particularly in education. The first schools for girls opened in 1858, followed by a boom in 1869 when elementary education became mandatory. In 1863, the first middle-level schools and a teacher training college opened. Whereas men’s education focused on job training, women’s education focused on shaping better Muslim wives and mothers with refined social graces.[8]

The movement for women’s education was sparked in large part by women’s magazines, the most recognized of which was Hanimlara Mahsus Gazete (The Ladies’ Own Gazette), which ran for fourteen years and was successful to found its own press. With managing editors and staff writers being almost all women, the magazine aimed to enable women to be better mothers, wives, and Muslims. Its topics shifted from “discussions of feminism, fashion, economic imperialism and autonomy, including patterns for home sewing of European fashions and advertisements for Singer sewing machines, comparisons of Ottoman modernization with Japanese modernization, technology, and the usual matter of a middle class women’s magazine of the nineteenth century: royal gossip, scientific housewifery, health, improving fiction, and childrearing.”[9]

Politics

Women of the imperial harem rose into much greater power during the sixteenth century. From roughly 1520, when Süleyman the Magnificent ascended to the throne, and reaching into the mid-seventeenth century is the period known as the “sultanate of women.” During this time, high-ranking women attained a large amount of political power and public importance. Aiding in domestic politics, foreign negotiations, and even serving as regents, the queen mothers and lead concubines in particular took on a great deal of political power and aided in imperial legitimation in that time.[10]

Legal Advice of mufti Ramli

Khayr al-Din Ramli was a seventeenth-century mufti from Palestine who provided legal opinions that concerned the position of women in Islamic society regarding marriage, divorce, and violence.

Arranged Marriages

The mufti Ramli was presented a case about a girl who, being a minor, was married off by her brother. Once she reached adulthood, she wanted to annul her marriage. However, her husband argued that she wasn't able to do this, because her brother "had acted as an agent to her father".[11] :66 She, on the other hand, claimed her brother had married her off while her father was away on a journey. In response to this situation, Ramli expressed that "if her husband proved his claim, then her choice is cancelled".[11]:66 However, if her father had authorized the brother to arrange the marriage, then she was not able to annul the marriage. She only had a choice if the marriage was arranged with her brother as a guardian, because "only the father's and grandfather's marriage arrangements cannot be cancelled".[11]:66

Kidnapping

Another case regarding marriage arrangements concerned a virgin who, as an adult, was kidnapped by her brother and married off to an "unsuitable man".[11]:66 In response, Ramli expressed that the father had the right to separate the marriage due to the unsuitability of the husband, even if the marriage was consummated. The conditions being, however, that the woman was not pregnant or had given birth to children, had received the dower. However, if the woman was married off without consenting to it, she could just choose to divorce her husband without her father's intercession, since her brother was not a proxy.

Divorce and Annulment

In another case, woman was abandoned by her husband and suffered from him leaving her with no support or legal provider. "She therefore asked the Shafi to annul the marriage"[11]:66 and as proof brought two witnesses to support her claim. Her marriage was annulled and she went on to remarry. However, the first husband appeared again and wanted to cancel the judgement. To this, the mufti answered that once the whole process was done, the annulment was reasonable and nobody could nullify it.

Consummation

A man claimed that his adult wife, who was supposed to be a virgin, had been deflowered,[11]:67 which he found out after having intercourse with her several times. Ramli's legal judgment in this case was that the dowry was required and that her personal testimony in reference to her virginity was enough to prove her chastity prior to the marriage. Punishment and the negation of his testimony could also apply to the husband for accusing her without any evidence. If he accused her of adultery, he had to support his argument (if she requested so) by having four witnesses testify. Failure to do so could cause him legal penalties.

Violence Against Women

A man kidnapped a woman who was married to someone else and took her to the shaykh[11]:67 of the village who gave them hospitality. There, the man "consummated the marriage"[11]:67 with the argument that relations existed between him and the woman. This case was considered to be a serious crime, and according to Ramli, both the kidnapper and the shaykh deserved a beating and extensive imprisonment. Ramli even considered execution for these men, because he felt they had completely disobeyed God. Ramli expressed that people associated with this type of crime would be punished by God.

On another legal issue related to violence and women, a legally married person captured a virgin and deflowered her. She escaped and returned to her family, but then he wanted to forcefully take her away again. Ramli declared he should be prevented from doing this, but if he claimed shubba, there would be no haad[11]:68 punishment and he would just have to pay the dower. If he didn't claim shubba, and his actions were proven, a punishment would have to be applied to him. If the man was a muhsan,[12] then he would have to be stoned. In the case that he was not a muhsan, he should be flogged. Furthermore, Ramli also added that if the haad was cancelled, a dowry had to be paid.

References

- ↑ Esposito, John (2001), Women in Muslim family law, Syracuse University Press, ISBN 978-0815629085

- ↑ Suraiya Faroqhi, Subjects of the Sultan: Culture and Daily Life in the Ottoman Empire. London: I.B. Tauris, November 29, 2005, 101.

- ↑ Marc Baer, “Islamic Conversion Narratives of Women: Social Change and Gendered Religious Hierarchy in Early Modern Ottoman Istanbul.” Gender & History, Vol.16 No.2 August 2004, 426.

- 1 2 3 Faroqhi, 103.

- ↑ Elizabeth B. Frierson, “Unimagined Communities: Women and Education in the Late Ottoman Empire, 1876-1909). Critical Matrix; Jan 1, 1995; 9, 2; 76.

- ↑ Faroqhi, 102.

- ↑ Faroqhi, 106.

- ↑ Reina Lewis, Rethinking Orientalism: Women, Travel and the Ottoman Harem. London: I.B. Tauris, 2004, 56.

- ↑ Frierson, 76.

- ↑ Leslie P. Peirce, The Imperial Harem: Women and Sovereignty in the Ottoman Empire. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993, vii.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Alfred, Andrea; Overfield, James. The Human Record: Sources of Global History. 2 (Fifth ed.). Boston.

- ↑ Kamali, Mohammed Hashim. "Punishment in Islamic Law: A Critique of the Hudud Bill of Kelantan, Malaysia". Archived from the original on 2007-10-06.