Women artists

While women artists have been involved in making art throughout history, their work often has not been as well acknowledged as that of men. Often certain media are associated with women artists, such as textile arts. Women's roles in relation to art, of course, vary in different cultures and communities. Many art forms considered to be created predominantly by women have been historically dismissed from the art historical canon as craft, as opposed to fine art.[1] Women artists faced challenges due to gender biases in the mainstream fine art world.[1] They have often encountered difficulties in training, travelling and trading their work, and gaining recognition. Beginning in the late 1960s and 1970s, feminist artists and art historians created a Feminist art movement that overtly addresses the role of women in the art world and explores the role of women in art history[1] and in society.

Prehistoric era

There are no records of who the artists of the prehistoric eras were, but studies of many early ethnographers and cultural anthropologists indicate that women often were the principal artisans in Neolithic cultures, in which they created pottery, textiles, baskets, painted surfaces and jewelry. Collaboration on large projects was typical. Extrapolation to the artwork and skills of the Paleolithic era suggests that these cultures followed similar patterns. Cave paintings of this era often have human hand prints, 75% of which are identifiable as women's.[2]

Ancient historical era

India

"For about three thousand years, the women – and only the women – of Mithila have been making devotional paintings of the gods and goddesses of the Hindu pantheon. It is no exaggeration, then, to say that this art is the expression of the most genuine aspect of Indian civilization."[3]

Classical Europe and the Middle East

The earliest records of western cultures rarely mention specific individuals, although women are depicted in all of the art and some are shown laboring as artists. Ancient references by Homer, Cicero, and Virgil mention the prominent roles of women in textiles, poetry, music, and other cultural activities, without discussion of individual artists. Among the earliest European historical records concerning individual artists is that of Pliny the Elder, who wrote about a number of Greek women who were painters, including Helena of Egypt, daughter of Timon of Egypt,[4][5] Some modern critics posit that Alexander Mosaic might not have been the work of Philoxenus, but of Helena of Egypt. One of the few named women painters who might have worked in Ancient Greece,[6][7] she was reputed to have produced a painting of the battle of Issus which hung in the Temple of Peace during the time of Vespasian.[8] Other women include Timarete, Eirene, Kalypso, Aristarete, Iaia, and Olympias. While only some of their work survives, in Ancient Greek pottery there is a caputi hydria in the Torno Collection in Milan.[9] It is attribute to the Leningrad painter from circa 460-450 B.C. and shows women working alongside men in a workshop where both painted vases.[10]

Europe

Medieval period

Hildegard of Bingen, "Universal Man" illumination from Hildegard's Liber Divinorum Operum, 1165

Hildegard of Bingen, "Universal Man" illumination from Hildegard's Liber Divinorum Operum, 1165 Hildegard von Bingen, Motherhood from the Spirit and the Water, 1165, from Liber divinorum operum, Benediktinerinnenabtei Sankt Hildegard, Eibingen (bei Rüdesheim)

Hildegard von Bingen, Motherhood from the Spirit and the Water, 1165, from Liber divinorum operum, Benediktinerinnenabtei Sankt Hildegard, Eibingen (bei Rüdesheim)

Artists from the Medieval period include Claricia, Diemudus, Ende, Guda, Herrade of Landsberg and Hildegard of Bingen. In the early Medieval period, women often worked alongside men. Manuscript illuminations, embroideries, and carved capitals from the period clearly demonstrate examples of women at work in these arts. Documents show that they also were brewers, butchers, wool merchants, and iron mongers. Artists of the time period, including women, were from a small subset of society whose status allowed them freedom from these more strenuous types of work. Women artists often were of two literate classes, either wealthy aristocratic women or nuns. Women in the former category often created embroideries and textiles; those in the later category often produced illuminations.

There were a number of embroidery workshops in England at the time, particularly at Canterbury and Winchester; Opus Anglicanum or English embroidery was already famous across Europe – a 13th-century papal inventory counted over two hundred pieces. It is presumed that women were almost entirely responsible for this production. One of the most famous embroideries of the Medieval period is the Bayeux Tapestry, which was embroidered with wool and is 230 feet long. Its images narrate the Battle of Hastings and the Norman Conquest of England. The Bayeux Tapestry may have been created in either a commercial workshop by a royal or an aristocratic lady and her retinue, or in a workshop in a nunnery. In the 14th century, a royal workshop is documented, based at the Tower of London, and there may have been other earlier arrangements. Manuscript illumination affords us many of the named artists of the Medieval Period including Ende, a 10th-century Spanish nun; Guda, a 12th-century German nun; and Claricia, a 12th-century laywoman in a Bavarian scriptorium. These women, and many more unnamed illuminators, benefited from the nature of convents as the major loci of learning for women in the period and the most tenable option for intellectuals among them.

In many parts of Europe, with the Gregorian Reforms of the 11th century and the rise in feudalism, women faced many strictures that they did not face in the Early Medieval period. With these societal changes, the status of the convent changed. In the British Isles, the Norman Conquest marked the beginning of the gradual decline of the convent as a seat of learning and a place where women could gain power. Convents were made subsidiary to male abbots, rather than being headed by an abbess, as they had been previously. In Pagan Scandinavia (in Sweden) the only historically confirmed female runemaster, Frögärd i Ösby, worked ca. 1000–1017.[11][12]

In Germany, however, under the Ottonian Dynasty, convents retained their position as institutions of learning. This might be partially because convents were often headed and populated by unmarried women from royal and aristocratic families. Therefore, the greatest late Medieval period work by women originates in Germany, as exemplified by that of Herrade of Landsberg and Hildegard of Bingen. Hildegard of Bingen (1098–1179) is a particularly fine example of a German Medieval intellectual and artist. She wrote The Divine Works of a Simple Man, The Meritorious Life, sixty-five hymns, a miracle play, and a long treatise of nine books on the different natures of trees, plants, animals, birds, fish, minerals, and metals. From an early age, she claimed to have visions. When the Papacy supported these claims by the headmistress, her position as an important intellectual was galvanized. The visions became part of one of her seminal works in 1142, Scivias (Know the Ways of the Lord), which consists of thirty-five visions relating and illustrating the history of salvation. The illustrations in the Scivias, as exemplified in the first illustration, depict Hildegarde experiencing visions while seated in the monastery at Bingen. They differ greatly from others created in Germany during the same period, as they are characterized by bright colors, emphasis on line, and simplified forms. While Hildegard likely did not pen the images, their idiosyncratic nature leads one to believe they were created under her close supervision.

The 12th century saw the rise of the city in Europe, along with the rise in trade, travel, and universities. These changes in society also engendered changes in the lives of women. Women were allowed to head their husbands' businesses if they were widowed. The Wife of Bath in Chaucer's The Canterbury Tales is one such case. During this time, women also were allowed to be part of some artisan guilds. Guild records show that women were particularly active in the textile industries in Flanders and Northern France. Medieval manuscripts have many marginalia depicting women with spindles. In England, women were responsible for creating Opus Anglicanum, or rich embroideries for ecclesiastical or secular use on clothes and various types of hangings. Women also became more active in illumination. A number of women likely worked alongside their husbands or fathers, including the daughter of Maître Honoré and the daughter of Jean le Noir. By the 13th century most illuminated manuscripts were being produced by commercial workshops, and by the end of the Middle Ages, when production of manuscripts had become an important industry in certain centres, women seem to have represented a majority of the artists and scribes employed, especially in Paris. The movement to printing, and of book illustration to the printmaking techniques of woodcut and engraving, where women seem to have been little involved, represented a setback to the progress of women artists.

Renaissance

St. Catherine of Bologna (Caterina dei Vigri), (Maria und das Jesuskind mit Frucht), c. 1440s. She is the patron saint of artists.

St. Catherine of Bologna (Caterina dei Vigri), (Maria und das Jesuskind mit Frucht), c. 1440s. She is the patron saint of artists.

Sofonisba Anguissola, Self-Portrait, 1554

Sofonisba Anguissola, Self-Portrait, 1554 Esther Inglis, Portrait, 1595

Esther Inglis, Portrait, 1595 Fede Galizia, Judith with the Head of Holofernes, 1596. The figure of Judith is believed to be a self-portrait.

Fede Galizia, Judith with the Head of Holofernes, 1596. The figure of Judith is believed to be a self-portrait.

Artists from the Renaissance era include Sofonisba Anguissola, Lucia Anguissola, Lavinia Fontana, Fede Galizia, Diana Scultori Ghisi, Caterina van Hemessen, Esther Inglis, Barbara Longhi,[13] Maria Ormani,[14] Marietta Robusti (daughter of Tintoretto),[13] Properzia de' Rossi,[13] Plautilla Nelli, Levina Teerlinc, Mayken Verhulst, and St. Catherine of Bologna (Caterina dei Vigri).

This is the first period in Western history in which a number of secular female artists gained international reputations. The rise in women artists during this period may be attributed to major cultural shifts. One such shift was a move toward humanism, a philosophy affirming the dignity of all people, that became central to Renaissance thinking and helped raise the status of women. In addition, the identity of the individual artist in general was regarded as more important; significant artists from this period whose identities are unknown virtually cease to exist. Two important texts, On Famous Women and The City of Women, illustrate this cultural change. Boccaccio, a 14th-century humanist, wrote De mulieribus claris (Latin for On Famous Women) (1135–59), a collection of biographies of women. Among the 104 biographies he included was that of Thamar (or Thmyris), an ancient Greek vase painter. Curiously, among the 15th-century manuscript illuminations of On Famous Women, Thamar was depicted painting a self-portrait or perhaps painting a small image of the Virgin and Child. Christine de Pizan, a remarkable late medieval French writer, rhetorician, and critic, wrote Book of the City of Ladies in 1405, a text about an allegorical city in which independent women lived free from the slander of men. In her work she included real women artists, such as Anastasia, who was considered one of the best Parisian illuminators, although none of her work has survived. Other humanist texts led to increased education for Italian women.

The most notable of these was Il Cortegiano or The Courtier by 16th-century Italian humanist Baldassare Castiglione. This enormously popular work stated that men and women should be educated in the social arts. His influence made it acceptable for women to engage in the visual, musical, and literary arts. Thanks to Castiglione, this was the first period of renaissance history in which noblewomen were able to study painting. Sofonisba Anguissola was the most successful of these minor aristocrats who first benefited from humanist education and then went on to recognition as painters.[15] Artists who were not noblewomen were affected by the rise in humanism as well. In addition to conventional subject matter, artists such as Lavinia Fontana and Caterina van Hemessen began to depict themselves in self-portraits, not just as painters but also as musicians and scholars, thereby highlighting their well-rounded education. Along with the rise in humanism, there was a shift from craftsmen to artists. Artists, unlike earlier craftsmen, were now expected to have knowledge of perspective, mathematics, ancient art, and study of the human body. In the late Renaissance the training of artists began to move from the master's workshop to the Academy, and women began a long struggle, not resolved until the late 19th century, to gain full access to this training. Study of the human body required working from male nudes and corpses. This was considered essential background for creating realistic group scenes. Women were generally barred from training from male nudes, and therefore they were precluded from creating such scenes. Such depictions of nudes were required for the large-scale religious compositions, which received the most prestigious commissions.

Although many aristocratic women had access to some training in art, though without the benefit of figure drawing from nude male models, most of those women chose marriage over a career in art. This was true, for example, of two of Sofonisba Anguissola's sisters. The women recognized as artists in this period were either nuns or children of painters. Of the few who emerged as Italian artists in the 15th century, those known today are associated with convents. These artists who were nuns include Caterina dei Virgi, Antonia Uccello, and Suor Barbara Ragnoni. During the 15th and 16th centuries, the vast majority of women who gained any modicum of success as artists were the children of painters. This is likely because they were able to gain training in their fathers' workshops. Examples of women artists who were trained by their fathers include the painter Lavinia Fontana, the miniature portraitist Levina Teerlinc, and the portrait painter Caterina van Hemessen. Italian women artists during this period, even those trained by their family, seem somewhat unusual. However, in certain parts of Europe, particularly northern France and Flanders, it was more common for children of both genders to enter into their father's profession. In fact, in the Low Countries where women had more freedom, there were a number of artists in the Renaissance who were women. For example, the records of the Guild of Saint Luke in Bruges show not only that they admit women as practicing members, but also that by the 1480s twenty-five percent of its members were women (many probably working as manuscript illuminators).

Baroque era

- Artemisia Gentileschi, Self-Portrait as a Lute Player, c. 1615-1617, Curtis Galleries, Minneapolis

Josefa de Ayala (Josefa de Óbidos), Still-life, c. 1679, Santarém, Municipal Library

Josefa de Ayala (Josefa de Óbidos), Still-life, c. 1679, Santarém, Municipal Library Giovanna Garzoni, Still Life with Bowl of Citrons, 1640, tempera on vellum, Getty Museum, Pacific Palisades, Los Angeles, California

Giovanna Garzoni, Still Life with Bowl of Citrons, 1640, tempera on vellum, Getty Museum, Pacific Palisades, Los Angeles, California Rachel Ruysch, Still-Life with Bouquet of Flowers and Plums, oil on canvas, Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts, Brussels

Rachel Ruysch, Still-Life with Bouquet of Flowers and Plums, oil on canvas, Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts, Brussels- Mary Beale, Self-portrait, c. 1675–1680

Élisabeth Sophie Chéron, self-portrait, 1672

Élisabeth Sophie Chéron, self-portrait, 1672

Artists from the Baroque era include: Mary Beale, Élisabeth Sophie Chéron, Maria Theresa van Thielen, Katharina Pepijn, Catharina Peeters, Johanna Vergouwen, Isabel de Cisneros, Giovanna Garzoni[13] Artemisia Gentileschi, Judith Leyster, Maria Sibylla Merian, Louise Moillon, Josefa de Ayala better known as Josefa de Óbidos, Maria van Oosterwijk, Magdalena de Passe, Clara Peeters, Maria Virginia Borghese (daughter of art collector Olimpia Aldobrandini),[16] Luisa Roldán known as La Roldana, Rachel Ruysch, Maria Theresa van Thielen, Anna Maria van Thielen, Francisca-Catherina van Thielen and Elisabetta Sirani. As in the Renaissance Period, many women among the Baroque artists came from artist families. Artemisia Gentileschi is an excellent example of this. She was trained by her father, Orazio Gentileschi, and she worked alongside him on many of his commissions. Luisa Roldán was trained in her father's (Pedro Roldán) sculpture workshop.

Women artists in this period began to change the way women were depicted in art. Many of the women working as artists in the Baroque era were not able to train from nude models, who were always male, but they were very familiar with the female body. Women such as Elisabetta Sirani created images of women as conscious beings rather than detached muses. One of the best examples of this novel expression is in Artemesia Gentileschi's Judith beheading Holofernes, in which Judith is depicted as a strong woman determining her own destiny. While other artists, including Botticelli and the more traditional woman, Fede Galizia, depicted the same scene with a passive Judith, in her novel treatment, Gentileschi's Judith appears to be an able actor in the task at hand. Action is the essence of it and another painting by her of Judith leaving the scene. Still life emerged as an important genre around 1600, particularly in the Netherlands. Women were at the forefront of this painting trend. This genre was particularly suited to women, as they could access the materials for still life readily. In the North, these practitioners included Clara Peeters, a painter of banketje or breakfast pieces, and scenes of arranged luxury goods; Maria van Oosterwijk, the internationally renowned flower painter; and Rachel Ruysch, a painter of visually charged flower arrangements. In other regions, still life was less common, but there were important women artists in the genre including Giovanna Garzoni, who created realistic vegetable arrangements on parchment, and Louise Moillon, whose fruit still life paintings were noted for their brilliant colors.

18th century

Elisabeth Vigee-Le Brun (1755–1842), Self-portrait, c. 1780s, one of many she painted for sale

Elisabeth Vigee-Le Brun (1755–1842), Self-portrait, c. 1780s, one of many she painted for sale Rosalba Carriera (1675–1757), Self-portrait 1715

Rosalba Carriera (1675–1757), Self-portrait 1715 Ulrika Pasch, Self portrait, c. 1770

Ulrika Pasch, Self portrait, c. 1770 Anna Dorothea Therbusch, Self-portrait, 1777

Anna Dorothea Therbusch, Self-portrait, 1777 Maria Cosway, Self-portrait, 1787

Maria Cosway, Self-portrait, 1787 Marguerite Gérard, First steps, oil on canvas, 45.5 x 55 cm, ca. 1788

Marguerite Gérard, First steps, oil on canvas, 45.5 x 55 cm, ca. 1788

Artists from this period include, Rosalba Carriera, Maria Cosway, Marguerite Gérard, Angelica Kauffman, Adélaïde Labille-Guiard, Giulia Lama, Mary Moser, Ulrika Pasch, Adèle Romany, Anna Dorothea Therbusch, Anne Vallayer-Coster, and Elisabeth Vigée-Le Brun.

In many countries of Europe, the Academies were the arbiters of style. The Academies also were responsible for training artists, exhibiting artwork, and, inadvertently or not, promoting the sale of art. Most Academies were not open to women. In France, for example, the powerful Academy in Paris had 450 members between the 17th century and the French Revolution, and only fifteen were women. Of those, most were daughters or wives of members. In the late 18th century, the French Academy resolved not to admit any women at all. The pinnacle of painting during the period was history painting, especially large scale compositions with groups of figures depicting historical or mythical situations. In preparation to create such paintings, artists studied casts of antique sculptures and drew from male nudes. Women had limited, or no access to this Academic learning, and as such there are no extant large-scale history paintings by women from this period. Some women made their name in other genres such as portraiture. Elisabeth Vigee-Lebrun used her experience in portraiture to create an allegorical scene, Peace Bringing Back Plenty, which she classified as a history painting and used as her grounds for admittance into the Academy. After the display of her work, it was demanded that she attend formal classes, or lose her license to paint. She became a court favourite, and a celebrity, who painted over forty self-portraits, which she was able to sell.[15]

In England, two women, Angelica Kauffman and Mary Moser, were founding members of the Royal Academy of Arts in London in 1768. Kauffmann helped Maria Cosway enter the Academy. Although Cosway went on to gain success as a painter of mythological scenes, both women remained in a somewhat ambivalent position at the Royal Academy, as evidenced by the group portrait of The Academicians of the Royal Academy by Johan Zoffany now in The Royal Collection. In it, only the men of the Academy are assembled in a large artist studio, together with nude male models. For reasons of decorum given the nude models, the two women are not shown as present, but as portraits on the wall instead.[17] The emphasis in Academic art on studies of the nude during training remained a considerable barrier for women studying art until the 20th century, both in terms of actual access to the classes and in terms of family and social attitudes to middle-class women becoming artists. After these three, no woman became a full member of the Academy until Laura Knight in 1936, and women were not admitted to the Academy's schools until 1861. By the late 18th century, there were important steps forward for artists who were women. In Paris, the Salon, the exhibition of work founded by the Academy, became open to non-Academic painters in 1791, allowing women to showcase their work in the prestigious annual exhibition. Additionally, women were more frequently being accepted as students by famous artists such as Jacques-Louis David and Jean-Baptiste Greuze.

19th century

Marie Ellenrieder, Self-portrait as a Painter, 1819

Marie Ellenrieder, Self-portrait as a Painter, 1819 Edmonia Lewis, The Death of Cleopatra detail, marble, 1876, Smithsonian American Art Museum

Edmonia Lewis, The Death of Cleopatra detail, marble, 1876, Smithsonian American Art Museum Mary Cassatt, Tea, 1880, oil on canvas, 25½ × 36¼ in., Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Mary Cassatt, Tea, 1880, oil on canvas, 25½ × 36¼ in., Museum of Fine Arts, Boston Maria Bashkirtseva, In the Studio, 1881, oil on canvas, 74 × 60.6 in, Dnipropetrovsk State Art Museum

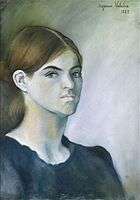

Maria Bashkirtseva, In the Studio, 1881, oil on canvas, 74 × 60.6 in, Dnipropetrovsk State Art Museum Suzanne Valadon, Self-portrait, 1883

Suzanne Valadon, Self-portrait, 1883 Berthe Morisot, L'Enfant au Tablier Rouge, 1886, American Art Museum

Berthe Morisot, L'Enfant au Tablier Rouge, 1886, American Art Museum Jeanna Bauck, The Danish Artist Bertha Wegmann Painting a Portrait, late 19th century

Jeanna Bauck, The Danish Artist Bertha Wegmann Painting a Portrait, late 19th century Olga Boznańska, Girl with Chrysanthemums, 1894, National Museum, Kraków

Olga Boznańska, Girl with Chrysanthemums, 1894, National Museum, Kraków

Artists from this period include Lucy Bacon, Marie Bashkirtseff, Anna Boch, Rosa Bonheur, Olga Boznańska, Marie Bracquemond, Mary Cassatt, Camille Claudel, Marie Ellenrieder, Kate Greenaway, Kitty Lange Kielland, Edmonia Lewis, Constance Mayer, Victorine Meurent, Berthe Morisot, Suzanne Valadon, Enid Yandell, and Wilhelmina Weber Furlong among others. Marie Ellenrieder and Marie-Denise Villers worked in the field of portraiture in the beginning of the century, and Rosa Bonheur in realist painting and sculpture. Elizabeth Jane Gardner was an American academic painter who was the first American woman to exhibit at the Paris Salon. In 1872 she became the first woman to ever win a gold medal at the Salon. Olga Boznańska is considered the best-known of all Polish women artists, and was stylistically associated with French Impressionism. Barbara Bodichon, Eleanor Fortescue-Brickdale, Kate Bunce, Evelyn De Morgan, Emma Sandys, Elizabeth Siddal, Marie Spartali Stillman, and Maria Zambaco [18] were women artists of the Pre-Raphaelite movement.

During the century, access to academies and formal art training expanded more for women in Europe and North America. The British Government School of Design, which later became the Royal College of Art, admitted women from its founding in 1837, but only into a "Female School" which was treated somewhat differently, with "life"- classes consisting for several years of drawing a man wearing a suit of armour. The Royal Academy Schools finally admitted women beginning in 1861, but students drew initially only draped models. However, other schools in London, including the Slade School of Art from the 1870s, were more liberal. By the end of the century women were able to study the naked, or very nearly naked, figure in many Western European and North American cities. The Society of Female Artists (now called The Society of Women Artists) was established in 1855 in London and has staged annual exhibitions since 1857, when 358 works were shown by 149 women, some using a pseudonym.[19]

Julia Margaret Cameron and Gertrude Kasebier became well known in the new medium of photography, where there were no traditional restrictions, and no established training, to hold them back. Elizabeth Thompson (Lady Butler), perhaps inspired by her life-classes of armoured figures at the Government School, was one of the first women to become famous for large history paintings, specializing in scenes of military action, usually with many horses, most famously Scotland Forever!, showing a cavalry charge at Waterloo. Berthe Morisot and the Americans, Mary Cassatt and Lucy Bacon, became involved in the French Impressionist movement of the 1860s and 1870s. American Impressionist Lilla Cabot Perry was influenced by her studies with Monet and by Japanese art in the late 19th century. Cecilia Beaux was an American portrait painter who also studied in France. In the late 19th century, Edmonia Lewis, an African-Ojibwe-Haitian American artist from New York began her art studies at Oberlin College. Her sculpting career began in 1863. She established a studio in Rome, Italy and exhibited her marble sculptures through Europe and the United States.[20] In 1894, Suzanne Valadon was the first woman admitted to the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts in France. Laura Muntz Lyall, a post-impressionist painter, exhibited at the 1893 World Columbian Exposition in Chicago, Illinois, and then in 1894 as part of the Société des artistes français in Paris.

English women painters from the early 19th century who exhibited at the Royal Academy of Art

- Sophie Gengembre Anderson

- Mary Baker

- Ann Charlotte Bartholomew

- Maria Bell

- Barbara Bodichon

- Joanna Mary Boyce

- Margaret Sarah Carpenter

- Fanny Corbaux

- Rosa Corder

- Mary Ellen Edwards

- Harriet Gouldsmith

- Mary Harrison (artist)

- Jane Benham Hay

- Anna Mary Howitt

- Mary Moser

- Martha Darley Mutrie

- Ann Mary Newton

- Emily Mary Osborn

- Kate Perugini

- Louise Rayner

- Ellen Sharples

- Rolinda Sharples

- Rebecca Solomon

- Elizabeth Emma Soyer

- Isabelle de Steiger

- Henrietta Ward

20th century

_(3803689322).jpg) Margaret Macdonald Mackintosh, The May Queen, 1900 [21]

Margaret Macdonald Mackintosh, The May Queen, 1900 [21] Hilma af Klint, Svanen (The Swan), No. 17, Group IX, Series SUW, October 1914-March 1915. This abstract work was never exhibited during af Klint's lifetime.

Hilma af Klint, Svanen (The Swan), No. 17, Group IX, Series SUW, October 1914-March 1915. This abstract work was never exhibited during af Klint's lifetime. Zinaida Serebriakova, The Harvest, 1915

Zinaida Serebriakova, The Harvest, 1915 Aleksandra Ekster, Costume design for Romeo and Juliette, 1921, M.T. Abraham Foundation

Aleksandra Ekster, Costume design for Romeo and Juliette, 1921, M.T. Abraham Foundation Tamara de Lempicka, The Musician, 1929

Tamara de Lempicka, The Musician, 1929 Georgia O'Keeffe, Ram's Head White Hollyhock and Little Hills, 1935, the Brooklyn Museum

Georgia O'Keeffe, Ram's Head White Hollyhock and Little Hills, 1935, the Brooklyn Museum- Alina Szapocznikow Grands Ventres, 1968, in the Kröller-Müller Museum

Notable women artists from this period include:[22]

Hannelore Baron, Lee Bontecou, Louise Bourgeois, Romaine Brooks, Emily Carr, Leonora Carrington, Mary Cassatt, Elizabeth Catlett, Camille Claudel, Sonia Delaunay, Marisol Escobar, Dulah Marie Evans, Audrey Flack, Mary Frank, Helen Frankenthaler, Elisabeth Frink, Wilhelmina Weber Furlong, Françoise Gilot, Natalia Goncharova, Nancy Graves, Grace Hartigan, Barbara Hepworth, Eva Hesse, Sigrid Hjertén, Hannah Höch, Frances Hodgkins, Malvina Hoffman, Margaret Ponce Israel, Gwen John, Käthe Kollwitz, Lee Krasner, Frida Kahlo, Hilma af Klint, Laura Knight, Barbara Kruger, Marie Laurencin, Tamara de Lempicka, Séraphine Louis, Dora Maar, Margaret Macdonald Mackintosh, Maruja Mallo, Agnes Martin, Ana Mendieta, Joan Mitchell, Paula Modersohn-Becker, Gabriele Münter, Alice Neel, Louise Nevelson, Georgia O'Keeffe, Orovida Camille Pissarro, Irene Rice Pereira, Bridget Riley, Verónica Ruiz de Velasco, Anne Ryan, Charlotte Salomon, Augusta Savage, Zofia Stryjeńska, Zinaida Serebriakova, Sarai Sherman, Henrietta Shore, Sr. Maria Stanisia, Marjorie Strider, Carrie Sweetser, Suzanne Valadon, Remedios Varo, Maria Helena Vieira da Silva, Nellie Walker, Marianne von Werefkin and Ogura Yuki.

Hilma af Klint (1862–1944) was a pioneer abstract painter, working long before her abstract expressionist male counterparts. She was Swedish and regularly exhibited her paintings dealing with realism, but the abstract works were not shown until 20 years after her death, at her request. She considered herself to be a spiritualist and mystic. [23]

Margaret Macdonald Mackintosh (1865–1933) was a Scottish artist whose works helped define the "Glasgow Style" of the 1890s and early 20th century. She often collaborated with her husband, the architect and designer Charles Rennie Mackintosh, in works that had influence in Europe. She exhibited with Mackintosh at the 1900 Vienna Secession, where her work is thought to have had an influence on the Secessionists such as Gustav Klimt.[24]

Wilhelmina Weber Furlong (1878–1962) was an early American modernist in New York City. She made significant contributions to modern American art through her work at the Art Students League and the Whitney Studio Club.[25][26] Aleksandra Ekster and Lyubov Popova were Constructivist, Cubo-Futurist, and Suprematist artists well known and respected in Kiev, Moscow and Paris in the early 20th century. Among the other women artists prominent in the Russian avant-garde were Natalia Goncharova, Varvara Stepanova and Nadezhda Udaltsova. Sonia Delaunay and her husband were the founders of Orphism.

In the Art Deco era, Hildreth Meiere made large-scale mosaics and was the first woman honored with the Fine Arts Medal of the American Institute of Architects.[27] Tamara de Lempicka, also of this era, was an Art Deco painter from Poland. Sr. Maria Stanisia became a notable portraitist, mainly of clergy.[28] Georgia O'Keeffe was born in the late 19th century. She became known for her paintings, featuring flowers, bones, and landscapes of New Mexico. In 1927, Dod Procter's painting Morning was voted Picture of the Year in the Royal Academy Summer Exhibition, and bought by the Daily Mail for the Tate gallery.[29] Its popularity resulted in its showing in New York and a two-year tour of Britain.[30] Surrealism, an important artistic style in the 1920s and 1930s, had a number of prominent women artists, including Leonora Carrington, Kay Sage, Dorothea Tanning, and Remedios Varo.[15]

Lee Miller rediscovered solarization[31] and became a high fashion photographer. Dorothea Lange documented the Depression. Margaret Bourke-White created the industrial photographs that were featured on the cover and in the lead article of the first Life Magazine. Diane Arbus based her photography on outsiders to mainstream society. Graciela Iturbide's works dealt with Mexican life and feminism, while Tina Modotti produced "revolutionary icons" from Mexico in the 1920s.[32] Annie Leibovitz's photographic work was of rock and roll and other celebrity figures. Mary Carroll Nelson founded the Society of Layerists in Multi-Media (SLMM), whose artist members follow in the tradition of Emil Bisttram and the Transcendental Painting Group, as well as Morris Graves of the Pacific Northwest Visionary Art School. In the 1970s, Judy Chicago created The Dinner Party, a very important work of feminist art. Helen Frankenthaler was an Abstract Expressionist painter and she was influenced by Jackson Pollock. Lee Krasner was also an Abstract Expressionist artist and married to Pollock and a student of Hans Hofmann. Elaine de Kooning was a student and later the wife of Willem de Kooning, she was an abstract figurative painter. Anne Ryan was a collagist. Jane Frank, also a student of Hans Hofmann, worked with mixed media on canvas. In Canada, Marcelle Ferron was an exponent of automatism.

From the 1960s on, feminism led to a great increase in interest in women artists and their academic study. Notable contributions have been made by the art historians Germaine Greer, Linda Nochlin, Griselda Pollock and others. Some art historians such as Daphne Haldin have attempted to redress the balance of male-focused histories by compiling lists of women artists, though many of these efforts remain unpublished.[33] Figures like Artemesia Gentileschi and Frida Kahlo emerged from relative obscurity to become feminist icons. The Guerilla Girls, an anonymous group of females formed in 1985, were "the conscience of the art world." They spoke out about indifference and inequalities for gender and race, particularly in the art world. The Guerilla Girls have made many posters as a way of bringing attention, typically in a humorous way, to the community to raise awareness and create change. In 1996, Catherine de Zegher curated an exhibition of 37 great women artists from the twentieth century. The exhibition, Inside the Visible, that travelled from the ICA in Boston to the National Museum for Women in the Arts in Washington, the Whitechapel in London and the Art Gallery of Western Australia in Perth, included artists' works from the 1930s through the 1990s featuring Claude Cahun, Louise Bourgeois, Bracha Ettinger, Agnes Martin, Carrie Mae Weems, Charlotte Salomon, Eva Hesse, Nancy Spero, Francesca Woodman, Lygia Clark and Mona Hatoum among others.

Contemporary artists

Magdalena Abakanowicz, Nierozpoznani ("The Unrecognised Ones"), 2002, in the Cytadela

Magdalena Abakanowicz, Nierozpoznani ("The Unrecognised Ones"), 2002, in the Cytadela- Yayoi Kusama, Ascension of Polkadots on the Trees at the Singapore Biennale, 2006

Marina Abramović performing in "The Artist is Present" at the Museum of Modern Art, May 2010

Marina Abramović performing in "The Artist is Present" at the Museum of Modern Art, May 2010 Li Chevalier Installation displayed at the Contemporary Art Museum Rome, 2017

Li Chevalier Installation displayed at the Contemporary Art Museum Rome, 2017

In 1993, Rachel Whiteread was the first woman to win the Tate Gallery's Turner Prize. Gillian Wearing won the prize in 1997, when there was an all-woman shortlist, the other nominees being Christine Borland, Angela Bulloch and Cornelia Parker. In 1999, Tracey Emin gained considerable media coverage for her entry My Bed, but did not win. In 2006 the prize was awarded to abstract painter, Tomma Abts. In 2001, a conference called "Women Artists at the Millennium" was organized at Princeton University. A book by that name was published in 2006, featuring major art historians such as Linda Nochlin analysing prominent women artists such as Louise Bourgeois, Yvonne Rainer, Bracha Ettinger, Sally Mann, Eva Hesse, Rachel Whiteread and Rosemarie Trockel. Internationally prominent contemporary artists who are women also include Magdalena Abakanowicz, Marina Abramović, Jaroslava Brychtova, Lynda Benglis, Lee Bul, Sophie Calle, Janet Cardiff, Li Chevalier, Marlene Dumas, Marisol Escobar, Jenny Holzer, Runa Islam, Chantal Joffe, Yayoi Kusama, Karen Kilimnik, Sarah Lucas, Yoko Ono, Jenny Saville, Carolee Schneeman, Shazia Sikander, Lorna Simpson, Lisa Steele, Stella Vine, Kara Walker, Rebecca Warren, Bettina Werner and Susan Dorothea White.

Japanese artist Yayoi Kusama's paintings, collages, soft sculptures, performance art and environmental installations all share an obsession with repetition, pattern, and accumulation. Her work shows some attributes of feminism, minimalism, surrealism, Art Brut, pop art, and abstract expressionism, and is infused with autobiographical, psychological, and sexual content. She describes herself as an "obsessive artist". In November 2008, Christie's auction house New York sold her 1959 painting No. 2 for $5,100,000, the record price in 2008 for a work by a living female artist.[34] During 2010–2011, Pompidou Centre in Paris presented its curators' choice of contemporary women artists in a three-volume's exhibition named elles@Centrepompidou.[35] The museum showed works of major women artists from its own collection. 2010 saw Eileen Cooper elected as the first ever woman 'Keeper of the Royal Academy'. 1995 saw Dame Elizabeth Blackadder in the 300-year history made 'Her Majesty's painter and limber in Scotland, she was awarded the OBE in 1982.

An interesting genre of women's art is women's environmental art. As of December 2013, the Women Environmental Artists Directory listed 307 women environmental artists, such as Marina DeBris, Vernita Nemec and Betty Beaumont. DeBris uses beach trash to raise awareness of beach and ocean pollution.[36] and to educate children about beach trash.[37] Nemec recently used junk mail to demonstrate the complexity of modern life.[38] Beaumont has been described as a pioneer of environmental art[39] and uses art to challenge our beliefs and actions.[40]

Misrepresentation in art history

Women artists have often been mis-characterized in historical accounts, both intentionally and unintentionally; such misrepresentations have often been dictated by the socio-political mores of the given era.[41] There are a number of issues that lie behind this, including:

- Scarcity of biographical information

- Anonymity – Women artists were often most active in artistic expressions that were not typically signed. During the Early Medieval period, manuscript illumination was a pursuit of monks and nuns alike.[42]

- Painters' Guilds – In the Medieval and Renaissance periods, many women worked in the workshop system. These women worked under the auspices of a male workshop head, very often the artist's father. Until the twelfth century there is no record of a workshop headed by a woman, when a widow would be allowed to assume her husband's former position.[43] Often guild rules forbade women from attaining the various ranks leading to master,[44][45] so they remained "unofficial" in their status.

- Naming Conventions – the convention whereby women take their husbands' last names impedes research on female articles, especially in cases in which a work of unknown origin was signed only with a first initial and last name. Even the simplest biographical statements may be misleading. For example, one might say that Jane Frank was born in 1918, but in reality she was Jane Schenthal at birth—Jane "Frank" didn't exist until over twenty years later.[46] Examples like this create a discontinuity of identity for women artists.

- Mistaken identity and incorrect attribution – In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, work by women was often reassigned. Some unscrupulous dealers even went so far as to alter signatures, as in the case of some paintings by Judith Leyster (1630) that were reassigned to Frans Hals.[47][48][49] Marie-Denise Villers (1774–1821) was a French painter who specialized in portraits. Villers was a student of the French painter Girodet. Villers' most famous painting, Young Woman Drawing, (1801) is displayed in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The painting was attributed to Jacques-Louis David at one time, but was later realized to be Villers' work. It is considered to be a self-portrait of the artist.[50]

See also

- Lists of women artists

- List of 20th-century women artists

- List of female dancers

- List of female sculptors

- Australian feminist art timeline

- Beaver Hall Group

- Bonn Women's Museum

- Female comics creators

- Feminist art

- Feminist art movement

- Guerrilla Girls On Tour

- National Museum of Women in the Arts

- Native American women in the arts

- Women Environmental Artists Directory

- Women in dance

- Women in music

- Women in photography

- Women in the workforce

- Women Surrealists

- Women's Studio Workshop

- The Story of Women and Art, 2014 television documentary

- Women's writing (literary category)

Notes

- 1 2 3 Aktins, Robert. "Feminist art." Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles. 1997 (retrieved 23 Aug 2011)

- ↑ "Were the First Artists Mostly Women?" "National Geographic", October 9, 2013

- ↑ Vequaud, Ives, Women Painters of Mithila, Thames and Hudson, Ltd., London, 1977 p. 9

- ↑ Women in Art retrieved January 18, 2010

- ↑ The Ancient Library Retrieved January 18, 2010

- ↑ Stokstad; Oppenheimer; Addiss, p. 134

- ↑ Summers, p. 41

- ↑ Ptolemy Hephaestion New History (codex 190) Bibliotheca Photius

- ↑ The Caputi Hydria Retrieved June 16, 2010

- ↑ Fig.37 Retrieved June 16, 2010

- ↑ Åke Ohlmarks: FornNordiskt Lexikon (Ancient Nordic dictionary) (1994) (in Swedish)

- ↑ Erik Brate: Svenska runristare (Swedish runmasters) (1926) (in Swedish)

- 1 2 3 4 3 women artists in Italy Retrieved June 14, 2010

- ↑ patron saint of painters Retrieved June 14, 2010

- 1 2 3 Heller, Nancy G., Women Artists: An Illustrated History, Abbeville Press, Publishers, New York 1987 ISBN 978-0-89659-748-8

- ↑ Barker, Sheila, Canvas is for Commoners, Highlights from the Mediceo del Principato, medici.org, 2008-3-20.

- ↑ Zoffany, Johan (1771–1772). "The Royal Academicians". The Royal Collection. Retrieved March 20, 2007.

- ↑ Maria Zambaco Retrieved June 15, 2010

- ↑ "History", The Society of Women Artists. Retrieved 17 February 2008.

- ↑ "Biography – Chronology of Mary Edmonia Lewis." Edmonia Lewis. (retrieved 24 August 2011)

- ↑ "Wikigallery - The May Queen 1900, by Margaret MacDonald Mackintosh.".

- ↑ Women Artists of the 20th & 21st Centuries, retrieved on June 14, 2007.

- ↑ Tuchman, Maurice. The Spiritual in Art: Abstract Painting, 1890-1985. Abbeville Pr. ISBN 0896596699.

- ↑ "Margaret Macdonald".

- ↑ The Biography of Wilhelmina Weber Furlong: The Treasured Collection of Golden Heart Farm by Clint B. Weber, ISBN 0-9851601-0-1, ISBN 978-0-9851601-0-4

- ↑ Professor Emeritus James K. Kettlewell: Harvard,Skidmore College,Curator The Hyde Collection. Foreword to The Treasured Collection of Golden Heart Farm: ISBN 0-9851601-0-1, ISBN 978-0-9851601-0-4

- ↑ American Architects Directory (PDF) (Second ed.). R.R. Bowker. 1962. p. xxxix.

- ↑ "stmargaretofscotland.com".

- ↑ Houghton Mifflin Dictionary of Biography. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. 2003. p. 1241. ISBN 978-0618252107.

- ↑ "Dod Procter", Tate. Retrieved on 16 September 2009.

- ↑ Haworth-Booth, Mark (2007). The Art of Lee Miller. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-300-12375-3.

- ↑ Lowe, Sarah M., Tina Modootti: Photographs, Harry N. Abrams Inc., Publishers, 1995 p. 36

- ↑ Drummond Charig, Frankie (4 April 2016). "Daphne Haldin’s Archive and the 'Dictionary of Women Artists'". British Art Studies. Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art and Yale Center for British Art (2). doi:10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-02/still-invisible/018. Retrieved 28 May 2016.

- ↑ Haden-Guest, Anthony (2008-11-15). "New York art sales: 'I knew it was too good to last'". The Guardian. London.

- ↑ "Communiqué présentation 3e rotation de l’exposition “elles” - elles@centrepompidou".

- ↑ staff. "Our Town, Central". Orange County Register. Retrieved December 11, 2013.

- ↑ "OC... and Sculpture by the Sea!". Sutherland Public School.

- ↑ "Vernita Nemec Segments of Endless Junkmail". Artdaily.org, The First Art Newspaper on the Net. Retrieved December 11, 2013.

- ↑ "Distinguished Alumni Awards". UC Berkeley. Retrieved December 11, 2013.

- ↑ "Camouflaged Cells Betty Beaumont". Newfound Journal. 2 (1). Winter 2011. Retrieved December 11, 2013.

- ↑ Myers, Author: Nicole. "Women Artists in Nineteenth-Century France - Essay - Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History - The Metropolitan Museum of Art".

- ↑ Nuns as Artists: The Visual Culture of a Medieval Convent, Jeffrey F. Hamburger, University of California Press

- ↑ Prak, Maarten R. (2006). Craft Guilds in Early Modern Low Countries: Work, Power and Representation. Ashgate. p. 133. ISBN 0754653390.

- ↑ Dutch Seventeenth-Century Genre Painting: Its Stylistic and Thematic Evolution, Wayne Franits, Yale University Press, 2008, ISBN 0-300-10237-2, page 49

- ↑ Dutch Painting 1600–1800 Pelican history of art, ISSN 0553-4755, Yale University Press, p.129

- ↑ Stanton, Phoebe B., "The Sculptural Landscape of Jane Frank" World Cat monograph including b&w and color plates, 120pp. (A.S. Barnes: South Brunswick, New Jersey, and New York, 1968) ISBN 1-125-32317-5 [A second edition of this book was published in July 1969 (Yoseloff: London, ISBN 0-498-06974-5; also ISBN 978-0-498-06974-1). 144 pages, rare edition.]

- ↑ Hofstede de Groot, Cornelis. "Judith Leyster," Jahrbuch der Königlich Preussischen Kunstsammlungen vol. 14 (1893), pp. 190–198; 232.

- ↑ Hofrichter, Frima Fox. "Judith Leyster: Leading Star," Judith Leyster: A Dutch Master and Her World, (Yale University, 1993).

- ↑ Molenaer, Judith. "Leyster, Judith, Dutch, 1609 – 1660," National Gallery of Art website. Accessed Feb. 1, 2014.

- ↑ Hess, Thomas B. (1971). "Editorial: Is Women's Lib Medieval?". ARTnews. 69 (9).

Further reading

- Anscombe, Isabelle, A Woman's Touch: Women in Design from 1860 to the Present Day, Penguin, New York, 1985. ISBN 978-0-670-77825-6.

- Armstrong, Carol and Catherine de Zegher (eds.), Women Artists at the Millennium, The MIT Press, Cambridge, 2006. ISBN 978-0-262-01226-3.

- Bank, Mirra, Anonymous Was A Woman, Saint Martin's Press, New York, 1979. ISBN 978-0-312-13430-3.

- Broude, Norma, and Mary D. Garrard, The Power of Feminist Art, Harry N. Abrams, Inc. New York, 1995. ISBN 978-0-8109-2659-2.

- Brown, Betty Ann, and Arlene Raven, Exposures: Women and their Art, NewSage Press, Pasadena, CA, 1989. ISBN 978-0-939165-11-7.

- Callen, Anthea, Women Artists of the Arts and Crafts Movement, 1870–1914, Pantheon, N.Y., 1979. ISBN 978-0-394-73780-5.

- Caws, Mary Anne, Rudolf E. Kuenzli, and Gwen Raaberg, Surrealism and Women, MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, 1990. ISBN 978-0-262-53098-9.

- Chadwick, Whitney, Women, Art, and Society, Thames and Hudson, London, 1990. ISBN 978-0-500-20241-8.

- Chadwick, Whitney, Women Artists and the Surrealist Movement, Thames and Hudson, London, 1985. ISBN 978-0-500-27622-8.

- Chanchreek, K.L. and M.K. Jain, Eminent Women Artists, New Delhi, Shree Pub., 2007, xii, 256 p., ISBN 978-81-8329-226-9.

- Cherry, Deborah, Painting Women: Victorian Women Artists, Routledge, London, 1993. ISBN 978-0-415-06053-0.

- Chiarmonte, Paula, Women Artists in the United States: a Selective Bibliography and Resource Guide on the Fine and Decorative Arts, G. K. Hall, Boston, 1990. ISBN 978-0-8161-8917-5

- Deepwell, Katy (ed),Women Artists and Modernism,Manchester University Press,1998. ISBN 978-0-7190-5082-4.

- Deepwell, Katy (ed),New Feminist Art Criticism;Critical Strategies,Manchester University Press, 1995. ISBN 978-0-7190-4258-4.

- Fine, Elsa Honig, Women & Art, Allanheld & Schram/Prior, London, 1978. ISBN 978-0-8390-0187-4.

- Florence, Penny and Foster, Nicola, Differential Aesthetics, Ashgate, Burlington, 2000. ISBN 978-0-7546-1493-7.

- Greer, Germaine, The Obstacle Race: The Fortunes of Women Painters and Their Work, Farrar Straus Giroux, New York, 1979. ISBN 978-0-374-22412-7.

- Harris, Anne Sutherland and Linda Nochlin, Women Artists: 1550–1950, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Alfred Knopf, New York, 1976. ISBN 978-0-394-41169-9.

- Heller, Nancy G., Women Artists: An Illustrated History. 4th ed. New York: Abbeville Press, 2003. ISBN 978-0789207685.

- Henkes, Robert. The Art of Black American Women: Works of Twenty-Four Artists of the Twentieth Century, McFarland & Company, 1993.

- Hess, Thomas B. and Elizabeth C. Baker, Art and Sexual Politics: Why have there been no Great Women Artists?, Collier Books, New York, 1971

- (in French) Larue, Anne, Histoire de l’Art d’un nouveau genre, avec la participation de Nachtergael, Magali, Max Milo Éditions, 2014. ISBN 978-2315006076

- Marsh, Jan, The Pre-Raphaelite Sisterhood, St. Martin's Press, New York, 1985. ISBN 978-0-7043-0169-6.

- Marsh, Jan, Pre-Raphaelite Women: Images of Femininity in Pre-Raphaelite Art, Phoenix Illustrated, London, 1998. ISBN 978-0-7538-0210-6

- Marsh, Jan, and Pamela Gerrish Nunn, Pre-Raphaelite Women Artists, Thames and Hudson, London, 1998. ISBN 978-0-500-28104-8

- The National Museum of Women in the Arts, Harry N. Abrams, Inc., N.Y. 1987. ISBN 978-0-8109-1373-8.

- Nochlin, Linda, Women, Art, and Power and Other Essays, Harper & Row, New York, 1988. ISBN 978-0-06-435852-1.

- Parker, Rozsika, and Griselda Pollock, Framing Feminism: Art and the Women's Movement, 1970–1985, Pandora, London and New York, 1987. ISBN 978-0-86358-179-3.

- Parker, Rozsika, and Griselda Pollock, Old Mistresses: Women, Art & Ideology, Pantheon Books, New York, 1981. ISBN 978-0-7100-0911-1.

- Parker, Rozsika, The Subversive Stitch: Embroidery and the Making of the Feminine, Routledge, New York, 1984. ISBN 978-0-7043-4478-5.

- Petteys, Chris, Dictionary of Women Artists: an international dictionary of women artists born before 1900, G.K. Hall, Boston, 1985

- Pollock, Griselda, Vision and Difference: Femininity, Feminism and the Histories of Art, Routledge, London, 1988. ISBN 978-0-415-00722-1

- Pollock, Griselda, Generations and Geographies in the Visual Arts, Routledge, London, 1996. ISBN 978-0-415-14128-4

- Pollock, Griselda, (edited and introduction by Florence, Penny), Looking back to the Future, G&B Arts, Amsterdam, 2001. ISBN 978-90-5701-132-0

- Pollock, Griselda, Encounters in the Virtual Feminist Museum: Time, Space and the Archive, 2007. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-41374-9.

- Rosenthal, Angela, Angelica Kauffman: Art and Sensibility, London and New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006. ISBN 978-0-300-10333-5.

- Rubinstein, Charlotte Streifer, American Women Sculptors: A History of Women Working in Three Dimensions, G.K. Hall, Boston. 1990

- Sills, Leslie. Visions: Stories About Women Artists, Albert Whitman & Company, 1993.

- Slatkin, Wendy, Voices of Women Artists, Prentice Hall, N.J., 1993. ISBN 978-0-13-951427-2.

- Slatkin, Wendy, Women Artists in History: From Antiquity to the 20th Century, Prentice Hall, N.J., 1985. ISBN 978-0-13-027319-2.

- Tufts, Eleanor, American Women Artists, 1830–1930, The National Museum of Women in the Arts, 1987. ISBN 978-0-940979-02-4.

- Waller, Susan, Women Artists in the Modern Era: A Documentary History, Scarecrow Press Inc., London, 1991. ISBN 978-0-8108-4345-5.

- Watson-Jones, Virginia, Contemporary American Women Sculptors, Oryx Press, Phoenix, 1986. ISBN 978-0-89774-139-2

- de Zegher, Catherine, Inside the Visible, MIT Press, Massachusetts, 1996.

- de Zegher, Catherine and Teicher, Hendel (Eds.), 3 X Abstraction, Yale University Press, New Haven, Drawing Center, New York, 2005. ISBN 978-0-300-10826-2.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Female artists. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Self-portraits of women. |

- Collection of Works by Women Artists in Germany and Austria, 1800–1950

- Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art at the Brooklyn Museum

- n.paradoxa: international feminist art journal, scholarly writing about contemporary women artists and feminist theory.

- Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, non-profit organization for the promotion of women artists of the 20th Century

- Women Artists Self-Portraits and Representations of Womenhood from the Medieval Period to the Present

- Women Artists in History

- National Museum of Women in the Arts

- Pre-Raphaelite Women, Part D: The Art-Sisters Gallery

- Women's Art at the World's Columbian Exposition, Chicago 1893

- Gallery of Victorian and Edwardian Women Artists at the University of Iowa

- UK's Latest Art Magazine Polled Experts to list the 30 Greatest Women Artists. Features six pages of artist profiles.

- Colouring Outside The Lines. A UK zine interviewing female contemporary artists from around the world.

- Female Formal

- The Great Female Artists from the Middle Age to the Modern Age