Wobbler disease

Wobbler disease is a catchall term referring to several possible malformations of the cervical vertebrae that cause an unsteady (wobbly) gait and weakness in dogs and horses. A number of different conditions of the cervical (neck) spinal column cause similar clinical signs. These conditions may include malformation of the vertebrae, intervertebral disc protrusion, and disease of the interspinal ligaments, ligamenta flava, and articular facets of the vertebrae.[1] Wobbler disease is also known as cervical vertebral instability, cervical spondylomyelopathy (CSM), and cervical vertebral malformation (CVM). In dogs, the disease is most common in large breeds, especially Great Danes and Doberman Pinschers. In horses, it is not linked to a particular breed, though it is most often seen in tall, race-bred horses of Thoroughbred or Standardbred ancestry. It is most likely inherited to at least some extent in dogs and horses.

Wobbler disease in dogs

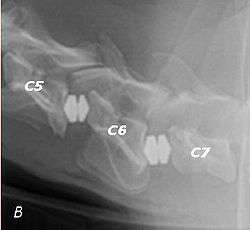

Wobbler disease is probably inherited in the Borzoi, Great Dane, Doberman, and Basset Hound.[2] Instability of the vertebrae of the neck (usually the caudal neck) causes spinal cord compression. In younger dogs such as Great Danes less than two years of age, wobbler disease is caused by stenosis (narrowing) of the vertebral canal[3] related to degeneration of the dorsal articular facets and subsequent thickening of the associated joint capsules and ligaments.[1] A high-protein diet may contribute to its development.[4] In middle-aged and older dogs such as Dobermans, intervertebral disc disease leads to bulging of the disc or herniation of the disc contents, and the spinal cord is compressed.[3] In Great Danes, the C4 to C6 vertebrae are most commonly affected; in Dobermans, the C5 to C7 vertebrae are affected.[5]

The disease tends to be gradually progressive. Symptoms such as weakness, ataxia, and dragging of the toes start in the rear legs. Dogs often have a crouching stance with a downward flexed neck. The disease progresses to the front legs, but the symptoms are less severe. Neck pain is sometimes seen. Symptoms are usually gradual in onset, but may progress rapidly following trauma.[6] X-rays may show misaligned vertebrae and narrow disk spaces, but it is not as effective as a myelogram, which reveals stenosis of the vertebral canal. Magnetic resonance imaging has been shown to be more effective at showing the location, nature, and severity of spinal cord compression than a myelogram.[7] Treatment is either medical to control the symptoms, usually with corticosteroids and cage rest, or surgical to correct the spinal cord compression. The prognosis is guarded in either case. Surgery may fully correct the problem, but it is technically difficult and relapses may occur. Types of surgery include ventral decompression of the spinal cord (ventral slot technique), dorsal decompression, and vertebral stabilization.[8] One study showed no significant advantage to any of the common spinal cord decompression procedures.[9] Another study showed that electroacupuncture may be a successful treatment for Wobbler disease.[10] A new surgical treatment using a proprietary medical device has been developed for dogs with disc-associated wobbler disease. It implants an artificial disc (cervical arthroplasty) in place of the affected disc space.[11]

Commonly affected dog breeds

- Great Dane

- Doberman

- St. Bernard

- Weimaraner

- German Shepherd Dog

- Boxer

- Basset Hound

- Rhodesian Ridgeback

- Dalmatian

- Samoyed

- Old English Sheepdog

- Bull Mastiff[4]

- Newfoundland

- Greyhound

- Rottweiler

T2 weighted MRI in neutral (A) and linear traction (B) of a seven-year-old Doberman with a two-year history of cervical pain treated with NSAIDs and presented acutely tretraplegic: A C6-C7 and C5-C6 traction responsive myelopathy are evident on MRI. The spinal-cord hyperintensity seen at the C5-C6 is suggestive of chronic lesion and most likely responsible for the chronic history of cervical pain, while the C5-C6 lesion was most likely responsible for the acute tetraplegia.

Same dog (A) treated with double implant (B) three days after surgery: The dog became ambulatory three days after surgery. Four weeks after surgery, it had ataxia without conscious proprioceptive deficits, and three months after surgery, the dog was neurologically normal. The owner reported it had been two years since the dog was able to hold its neck in an elevated position.

Wobbler disease in horses

Wobbler disease is also found in horses, where it is often called wobbler's syndrome; it refers to several conditions beyond those listed above, including equine wobbles anemia. It is also used as a catch-all phrase within the horse community to designate a neurological problem that has no more specific diagnosis. Some forms, such as cervical vertebral malformation, are not thought to be hereditary, but rather a congenital condition or a growth disorder. Other forms, such as equine wobbles anemia, are concentrated in certain breeds and may be hereditary to some extent. Horses with wobbler disease often exhibit ataxia (implying dysfunction of parts of the nervous system), show weakness in the hindquarters, or may knuckle over in their fetlocks, particularly in the rear. With advanced stages of the disease, they are prone to falling. While some cases are successfully treated with nutritional and medical management, surgery is also used. One method is the use of titanium baskets, placed to fuse the vertebrae, thereby preventing compression of the spinal cord. Some horses are able to return to work, with a few able to reach competitive levels. No complete cure for the condition is known.

Because wobbler's is the best known of the neurological conditions that affect horses, other, unrelated conditions, such as equine protozoal myeloencephalitis and cerebellar abiotrophy, are sometimes misdiagnosed as wobbler's, though the causes and symptoms differ.

Commonly affected horse breeds

References

- 1 2 Bagley, Rodney S. (2006). "Acute Spinal Disease" (PDF). Proceedings of the North American Veterinary Conference. Retrieved 2007-02-19.

- ↑ "Spinal Cord Disorders: Small Animals". The Merck Veterinary Manual. 2006. Retrieved 2007-02-19.

- 1 2 Chrisman, Cheryl; Clemmons, Roger; Mariani, Christopher; Platt, Simon (2003). Neurology for the Small Animal Practitioner (1st ed.). Teton New Media. ISBN 1-893441-82-2.

- 1 2 Ettinger, Stephen J.; Feldman, Edward C. (1995). Textbook of Veterinary Internal Medicine (4th ed.). W.B. Saunders Company. ISBN 0-7216-6795-3.

- ↑ Danourdis, Anastassios M. (2004). "The Diagnostic and Therapeutic Approach to Cervical Spondylomyelopathy". Proceedings of the 29th World Congress of the World Small Animal Veterinary Association. Retrieved 2007-02-19.

- ↑ Braund, K.G. (2003). "Degenerative and Compressive Structural Disorders". Braund's Clinical Neurology in Small Animals: Localization, Diagnosis and Treatment. Retrieved 2007-02-19.

- ↑ da Costa R, Parent J, Dobson H, Holmberg D, Partlow G (2006). "Comparison of magnetic resonance imaging and myelography in 18 Doberman pinscher dogs with cervical spondylomyelopathy". Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 47 (6): 523–31. PMID 17153059. doi:10.1111/j.1740-8261.2006.00180.x.

- ↑ Wheeler, Simon J. (2004). "Update on Spinal Surgery I: Cervical Spine". Proceedings of the 29th World Congress of the World Small Animal Veterinary Association. Retrieved 2007-02-19.

- ↑ Jeffery N, McKee W (2001). "Surgery for disc-associated wobbler syndrome in the dog--an examination of the controversy". J Small Anim Pract. 42 (12): 574–81. PMID 11791771. doi:10.1111/j.1748-5827.2001.tb06032.x.

- ↑ Sumano H, Bermudez E, Obregon K (2000). "Treatment of wobbler syndrome in dogs with electroacupuncture". Dtsch Tierarztl Wochenschr. 107 (6): 231–5. PMID 10916938.

- ↑ Adamo PF. "Cervical arthroplasty in two dogs with disk-associated cervical spondylomyelopathy". J Am Vet Med Assoc. 239: 808–17. PMID 21916764. doi:10.2460/javma.239.6.808.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Wobbler disease. |