Wind Cave National Park

| Wind Cave National Park | |

|---|---|

|

IUCN category II (national park) | |

|

Boxwork formation | |

Wind Cave | |

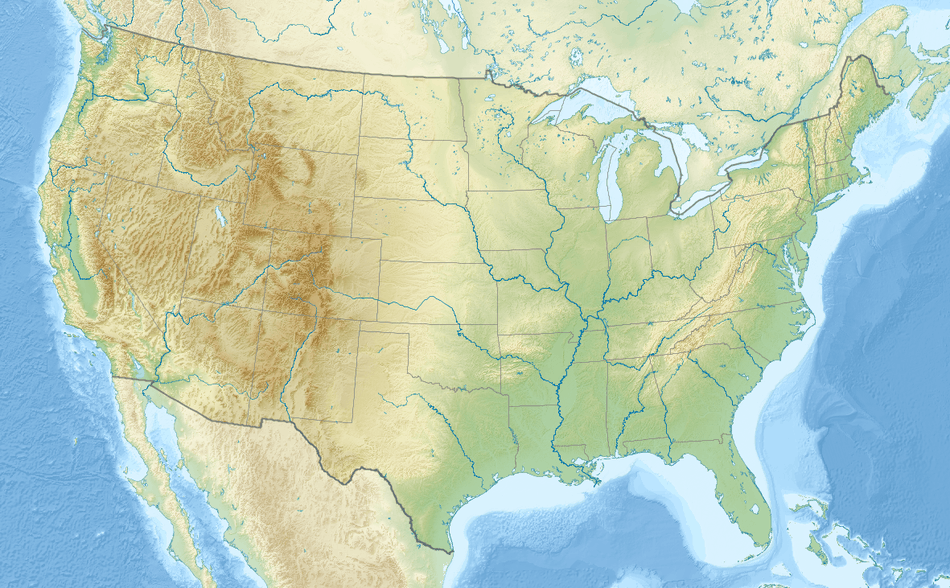

| Location | Custer County, South Dakota, USA |

| Nearest city | Hot Springs, South Dakota |

| Coordinates | 43°33′23″N 103°28′43″W / 43.55635°N 103.47865°WCoordinates: 43°33′23″N 103°28′43″W / 43.55635°N 103.47865°W |

| Area | 33,847 acres (136.97 km2)[1] |

| Established | January 9, 1903 |

| Visitors | 617,377 (in 2016)[2] |

| Governing body | National Park Service |

| Website | Official site |

|

| Black Hills and Badlands |

|---|

|

| Sculpture |

| Geologic formations |

| Mountains |

|

| Caves |

| Parks, forests, and grassland |

| Lakes |

Wind Cave National Park is a United States national park 10 miles (16 km) north of the town of Hot Springs in western South Dakota. Established in 1903 by President Theodore Roosevelt, it was the seventh U.S. National Park and the first cave to be designated a national park anywhere in the world. The cave is notable for its displays of the calcite formation known as boxwork. Approximately 95 percent of the world's discovered boxwork formations are found in Wind Cave. Wind Cave is also known for its frostwork. The cave is also considered a three-dimensional maze cave, recognized as the densest (most passage volume per cubic mile) cave system in the world. The cave is currently the sixth-longest in the world with 140.47 miles (226.06 km) of explored cave passageways.[3] Above ground, the park includes the largest remaining natural mixed-grass prairie in the United States.

Early knowledge

The Lakota, Cheyenne, and other Native American tribes who traveled through the area were aware of the cave's existence, as were early Euro-American settlers, but there has been no evidence yet discovered that anyone actually entered it.[4]

The Lakota (Sioux), an indigenous people who live in the Black Hills region of South Dakota, spoke of a hole that blew air, a place they consider sacred as the site where they first emerged from the underworld where they had lived before the demiurge creation of the world.[4]

The first documented discovery of the cave by White Americans was in 1881, when the brothers Tom and Jesse Bingham heard wind rushing out from a 10-inch (25 cm) by 14-inch (36 cm) hole in the ground. According to the story, when Tom looked into the hole, the "wind" (exiting cave air) blew his hat off of his head.[5]

Source of cave's name

The caves found in the park are said to "breathe," that is, air continually moves into or out of a cave, equalizing the atmospheric pressure of the cave and the outside air. When the air pressure is higher outside the cave than in it, air flows into the cave, raising cave's pressure to match the outside pressure. When the air pressure inside the cave is higher than outside it, air flows out of it, lowering the air pressure within the cave.[5] A large cave (such as Wind Cave) with only a few small openings will "breathe" more obviously than a small cave with many large openings.

Rapid weather changes, accompanied by rapid barometric changes, are a feature of Western South Dakota weather. If a fast-moving storm was approaching on the day the Bingham brothers found the cave, the atmospheric pressure would have been dropping fast, causing the cave's higher-pressure air to rush out all available openings, creating the "wind" for which Wind Cave was named.

Early exploration and tours

From 1881 to 1889, few people ventured far into Wind Cave. Then in 1889 the South Dakota Mining Company hired Jesse D. McDonald to oversee their "mining claim" on the cave site. The South Dakota Mining Company may have hoped to find minerals of value, or it may from the start have had commercial development of the cave in mind.[6]

No valuable mineral deposits were found, and the McDonald family began developing the cave for tourism. Jesse initially hired his son Alvin (age 16 in 1890) and, beginning in 1891, Alvin's brother Elmer, to explore and help develop the cave.[7] Alvin fell in love with the cave and kept a cave diary.[8] Others who worked at Wind Cave and helped explore it between 1890 and 1903 include Katie Stabler, Emma McDonald (Elmer's wife), Inez McDonald (Emma and Elmer's daughter), and Tommy McDonald (brother of Elmer and Alvin).[4]

By February 1892 the cave was open for visitors;[9] the standard tour fee was apparently $1.00,[10] which was a significant sum of money at the time.

Tourists, with their guide, explored the cave by candlelight. These early tours were physically demanding and sometimes involved crawling through narrow passages.

Like the nearby Jewel Cave National Monument, currently the third longest cave, Herb and Jan Conn played an important role in cave exploration during the 1960s.

Surface resources

Wind Cave National Park protects a diverse ecosystem with eastern and western plant and animal species. Many visible animals inhabit this park include raccoons, elk (also called wapiti), bison, coyotes, skunks, badgers, ermines, black-footed ferrets, cougars, bobcats, red foxes, minks, pronghorn and prairie dogs. The Wind Cave bison herd is one of only four free-roaming and genetically pure herds on public lands in North America. The other three herds are the Yellowstone Park bison herd, the Henry Mountains bison herd in Utah and on Elk Island in Alberta, Canada. The Wind Cave bison herd is currently brucellosis-free.[5]

Several roads run through the park and there are 30 miles (48 km) of hiking trails, so almost the entire park is accessible. The park had an estimated 617,377 visitors in 2016.[2] More than 109,000 people toured the cave itself in 2015, the most since 1968 before cave tours were limited to 40 people each.[11]

The Wind Cave Visitor Center features three exhibit rooms about the geology of the caves and early cave history, the park's wildlife and natural history, and the work of the Civilian Conservation Corps in the park.

Elk Mountain Campground, located in a ponderosa pine forest, is about 1.25 miles (2.0 km) from the visitor center. There are 75 sites for tents and recreational vehicles. It is open year-round with campfire programs offered in the summer and limited services available in the winter.[5] As of March 2013, the campground has been closed due to budget cuts stemming from the United States budget sequestration law. However, the decision to close the campground was reversed, and it has been available since May 24, 2013.[12]

Geology

The three levels making up the Wind Cave system are located in the upper 76 m of the Mississippian Pahasapa (Madison) Limestone. Deposited in an inland sea, chert, gypsum, and anhydrite lenses within the limestone are evidence of high periods of evaporation. When sea levels dropped at the end of the Mississippian, dissolution of the limestone formed a Kaskaskia paleokarst terrain, complete with solution fissures, sinkholes, and caves. Thus, an unconformity exists between this limestone and the overlying Pennsylvanian Minnelusa Formation. These red sands and clays filled in cavities. Those cavities not filled in were coated in dogtooth spar. Subsequent deposition of the Permian Opeche Shale, Permian Minnekahta Limestone, Triassic Spearfish Formation, and Tertiary White river Group followed. Paleocene and Eocene erosion removed these overlying sediments, in the area of the caves, down to the Minnelusa. Geologic uplift started during the Laramide Orogeny, which lowered the water table, draining the cave system and enlarging it. Today the water level is 150 m below the surface, which amounts to a drop of 0.4 m every 1000 years.[13]

Boxwork was first noted in Wind Cave. These calcite fins were once crack filling gypsum and anhydrite. Calcite-gypsum pseudomorphs are common. The released sulfuric acid weakened the bedrock, allowing it to weather faster than the calcite. The resultant intersecting fins form open chambers and protrude from the surrounding bedrock by amounts ranging from 0.6 to 1.2 m. Lower levels of the cave have boxworks mixed with frostwork and cave popcorn. Helictite bushes were also first discovered in Wind Cave. Moonmilk is found on many surfaces, while calcite rafts are found in the lower levels of the cave system.[13]:18,20-21

See also

- Carlsbad Caverns National Park

- Jewel Cave National Monument

- Great Basin National Park (Lehman Caves)

- Lava Beds National Monument (lava tube caves)

- Mammoth Cave National Park

- Oregon Caves National Monument

- Russell Cave National Monument

- Timpanogos Cave National Monument

References

- ↑ "Listing of acreage as of December 31, 2011". Land Resource Division, National Park Service. Retrieved March 7, 2012.

- 1 2 "NPS Annual Recreation Visits Report". National Park Service. Retrieved February 9, 2017.

- ↑ Gulden, Bob (May 13, 2013). "Worlds longest caves". Geo2 Committee on Long and Deep Caves. National Speleological Society (NSS). Retrieved June 12, 2013.

- 1 2 3 National Park Service: Early cave explorers

- 1 2 3 4 Wind Cave brochure, National Park Service, GPO, WDC

- ↑ http://www.nps.gov/wica/historyculture/alvin_mcdonald.htm

- ↑ McDonald, Alvin Frank. A Private Account of A. F. McDonald, Permanent Guide of Wind Cave (a.k.a. "Alvin McDonald Diary," written 1891-1893). Facsimile ed., no pub. data. Sold through Wind Cave National Park. Financial entries, pp. 20-21 and 23-25.

- ↑ http://www.nps.gov/wica/historyculture/alvin-mcdonalds-diary-text.htm

- ↑ McDonald, Alvin Frank. A Private Account of A. F. McDonald, Permanent Guide of Wind Cave (a.k.a. "Alvin McDonald Diary," written 1891-1893). Facsimile ed., no pub. data. Sold through Wind Cave National Park. Financial entries, p. 9

- ↑ McDonald, Alvin Frank. A Private Account of A. F. McDonald, Permanent Guide of Wind Cave (a.k.a. "Alvin McDonald Diary," written 1891-1893). Facsimile ed., no pub. data. Sold through Wind Cave National Park. Financial entries, p. 8-9

- ↑ Kent, Jim (January 19, 2016). "Wind Cave Numbers Highest In 40 Years". South Dakota Public Broadcasting. Retrieved January 19, 2016.

- ↑ Garrigan, Mary (8 May 2013). "Elk Mountain campground reopens May 24". Rapid City Journal. Retrieved 2013-06-12.

- 1 2 KellerLynn, K. (2009). Wind Cave National Park Geologic Resources Inventory Report, Natural Resource Report NPS/NRPC/GRD/NRR-2009/087. Denver: National Park Service. pp. 14–15,29–30.