Canada warbler

| Canada warbler | |

|---|---|

| |

| Male | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Parulidae |

| Genus: | Cardellina |

| Species: | C. canadensis |

| Binomial name | |

| Cardellina canadensis (Linnaeus, 1766) | |

| |

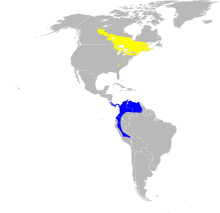

| Range of C. canadensis Breeding range Wintering range | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Wilsonia canadensis | |

The Canada warbler (Cardellina canadensis) is a small boreal songbird of the New World warbler family (Parulidae). It summers in Canada and northeastern United States and winters in northern South America.

Description

The Canada warbler is sometimes called the "necklaced warbler," because of the band of dark streaks across its chest. The adults have minimal sexual dimorphism, although the male's "necklace" is darker and more conspicuous and also has a longer tail. Adults are 12–15 cm (4.7–5.9 in) long, have a wingspan of 17–22 cm (6.7–8.7 in) and weigh 9–13 g (0.32–0.46 oz).[2]

The chest, throat and belly of the bird is yellow, and its back is dark grey. It has no wingbars or tail spots, but the underside of the tail is white. It has a yellow line in front of its eye in the direction of the beak, but the most striking facial feature is the white eyerings or "spectacles."[3]

Immature specimens have similar coloration as adults but duller and with less pronounced facial features.[3]

Population, range, habitat and life history

Partners in Flight estimates a global population of 4 million,[4] while the American Bird Conservancy estimates that 1.5 milion individuals exist.[5]

During the breeding season 82% of the population can be found in Canada and 18% in the United States.[2] In Canada the summer range extends from southeastern Yukon to Nova Scotia. In the United States the range extends from northern Minnesota to northern Pennsylvania, west to Long Island. It also nests in the high Appalachians as far south as Georgia.[6] In winter the Canada warbler's range extends from Guyana to northwestern Bolivia around the northern and western side of the Andean crest.[7]

In both summer and winter seasons the Canada warbler inhabits moist thickets. During the breeding season the bird

nests in riparian thickets, brushy ravines, forest bogs, etc. at a wide range of elevations and across a variety of forest types. In the northwestern parts of its range it frequents aspen forests; in the center of the range, it is found in forested wetlands and swamps; and in the south it occupies montane rhododendron thickets.[7]

In the winter it prefers mid- and upper-elevation habitats.[7] In northern Minnesota a study found that Canada warblers inhabited the shrub-forest edge, rather than marture forests or open fields with shrub.[8] In New England the Canada warbler was found to be "disturbance specialists" moving into patches of forests recovering from wind throw or timber removal.[9] Because of its preference for low-height foraging in deciduous forests, it may be bounded at higher elevations as suitable habitat disappears and suffer competition from the Black-throated blue warbler which prefers similar habitats.[10]

Two accidentals have been observed in Europe. The first a moribund male caught in Sandgerði, Iceland on September 29, 1973. The second was a first winter, probably female observed for five days in October 2006 in County Clare, Ireland.[11]

The age at which the young leave the nest is not known. Once independent they spend almost all their time in the understory, on the ground or in bushes.[6] The post-juvenile bird undergoes a partial moult involving all body feathres and wing coverlets. This may be completed before the first migration.[12]

The oldest known specimen was a male found in Quebec in 1982 at least 8 years old, having been banded in 1975.[13]

Behavior

Feeding

The Canada Warbler eats insects for the most part, including beetles, mosquitoes, flies, moths, and smooth caterpillars such as cankerworms, supplemented by spiders, snails, worms, and, at least seasonally, fruit.[7][6] It employs several foraging tactics, such as flushing insects from foliage and catching them on the wing (which it does more frequently than other warblers),[7] and searching upon the ground among fallen leaves.[6] When they occasionally hover glean, males tend to fly higher than females on breeding grounds.[7] In the tropics of South America, it forages in mixed flocks with other birds, usually 3–30 feet above ground in denser foliage.[6]

Song

The ![]() song of this bird is loud and highly variable, resembling chip chewy sweet dichetty. Their calls are low chup's.

song of this bird is loud and highly variable, resembling chip chewy sweet dichetty. Their calls are low chup's.

A 2013 study showed that male Canada warblers have two performance-encoded song types. In Mode I, used mostly during the day, when unpaired either alone or near a female during early nesting, involves stereotyped songs sung slowly and regularly. Mode II, used at dawn, after pairing and when near another male, involves variable songs, sung rapidly with irregular rhythm and chippipng between songs. Most of the phrases used were common to both modes, a feature unique among paulidswhich ordinarily have an individual's repertoire separated into two distinct parts.[14]

In 2000 in Giles County, Virginia, a female Canada warbler (or a post-hatching year old male that failed to moult, something never before observed) for the first time was observed singing. Its songs repertoire consisted of a repeated song of 12 to 13 notes as well as several shorter songs consisting of the first five or six notes of the longer song. The bird did not respond to playbacks of its own song or a recording of a male. Although female singing among the parulids has long been considered "idiosyncratic," singing by female Canada warblers is supported by observation of femaile singing in congener Wilson's warbler (C. pusilla) and the closely related hooded warbler (Setophaga citrina).[15]

Breeding and nesting

At least 60–65% of the population nests in boreal forests in Canada, the Great Lakes region of the United States, New England and through the Appalachians.[7] The birds are at least seasonally monogamous. Sightings of pairs during migration in Panama have led to the conclusion that they are permanently monogamous.[16][2] This conclusion, however, is contradicted by the sexes' wintering at different elevations.[7]

Males arrive at the breeding grounds in the first two weeks of May.[6] Females build the nests on or very close to the ground in dense cover. The nests are made up of root masses, hummocks, stumps, stream banks, mossy logs, and sometimes leaf litter and grass clumps. Moss covering is frequent.[7]

The female lays four to five eggs and incubates for about 12 days. The chicks remain in the nest for about 10 days after hatching and are dependent on their parents for two to three weeks after they leave the nest.[17]

Migration

The Canada warbler is one of the last birds to arrive at the breeding grounds and one of the first to leave. They may spend only two months there. They fly at night along a route generally south and west to the Texas coast, then to southern Mexico. The arrive at the winter grounds in northwestern South America in late September to early October.[7]

Diseases, parasites, etc.

In the summer of 1947 a single sepcimen of Canada warbler from Virgiinia (and one specimen of another warbler from Georgia_ were found to be hosts of a new species of acanthocephalan worm, which was named Apororynchus amphistomi, the third species of that genus and the first in North America.[18]

In the southern part of the breeding range, nest parasitism by cowbirds is frequent.[7]

Status

Threats to the Canada warbler include forest fragmentation; over-browsing of the understory by deer, acid rain, and the spread of the woolly adelgid (a killer of fir and hemlock trees).[5] Owing to thee factors the Breeding Bird Survey data show a population decline of 3.2 percent per year throughout the Canada Warbler's breeding range, with the greatest declines in the Northeast.[19][5] The species has been assessed as "threatened" by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada.[20] The IUCN, however, ranks the Canada warbler as a species of least concern.[1]

The Canada warbler is protected at the federal level in both Canada and the United States.[17]

In art

John James Audubon illustrates the Canada warbler in Birds of America (published, London 1827-38) as Plate 73 entitled "Bonaparte's Flycatching-Warbler—Muscicapa bonapartii." The single female (now properly identified as a Canada warbler) is shown perched in a Great Magnolia (Magnolia grandiflora) branch that was painted by Joseph Mason. The final, combined image was engraved and colored by Robert Havell Jr. at the Havell workshops in London. The original painting was purchased by the New York Historical Society.

References

- 1 2 BirdLife International (2009). "Wilsonia canadensis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2011.2. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved June 3, 2012. Database entry contains justification including this species in "least concern" category.

- 1 2 3 "Canada Warbler—Life History". Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Retrieved December 15, 2016.

- 1 2 "Canada Warbler—Identification". Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Retrieved December 15, 2016.

- ↑ "Species Assessment Database". Partners in Flight. Retrieved December 15, 2016.

- 1 2 3 "Canada Warbler". American Bird Conservancy. Retrieved December 15, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Canada Warbler". Audubon Guide to North American Birds. Retrieved December 15, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 "Canada warbler". Boreal Songbird Initiative. Retrieved December 15, 2016.

- ↑ Collins, Scott L.; James, Frances C.; Risser, Paul G. (1982). "Habitat Relationships of Wood Warblers Parulidae in Northern Central Minnesota". Oikos. 39 (1): 50–58. Retrieved December 18, 2016.

- ↑ Chace, Jameson F.; Faccio, Steven D.; Chacko, Abraham (2009). "Canada Warbler Habitat Use of Northern Hardwoods in Vermont". Northeastern Naturalist. pp. 491–500. Retrieved December 18, 2016 – via JSTR. (Subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Sabo, Stephen R. (June 1980). "Niche and Habitat Relations in Subalpine Bird Communities of the White Mountains of New Hampshire". Ecological Monographs. 50 (2): 241–59. doi:10.2307/1942481. Retrieved December 18, 2016 – via JSTOR. (Subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Hanafin, Maurice (2006). "The Canada Warbler in County Clare—The Second for Weatern Palearctic" (PDF). Birding World. 19 (10): 429–34. Retrieved December 17, 2016.

- ↑ Hanafin 2006, p. 434.

- ↑ USGS Patuxent Wildlife Research Center (2016). "Longevity Records of North American Birds". U.S. Geological Survey. Department of the Interior. Retrieved December 16, 2016.

- ↑ Demko, Alana D.; Reitsma, Leonard R.; Staicer, Cynthia A. (October 2013). "Two song categories in the Canada Warbler (Cardellina canadensis)". The Auk. 130 (4): 609–16. doi:10.1525/auk.2013.13059. Retrieved December 15, 2016 – via JSTOR. (Subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Etterson, Matthew A. (2003). "An Observation of Singing by a Female-Plumaged Canada Warbler". Southeastern Naturalist. 2 (2): 419–22. Retrieved December 17, 2016 – via JSTOR. (Subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Greenberg, Russell S.; Gradwohl, Judy A. (October 1980). "Observations of Paired Canada Warblers Wilsonia canadensis during Migration in Panama". Ibis. 122 (4): 509–12. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.1980.tb00907.x. Retrieved December 18, 2016 – via Wiley Online. (Subscription required (help)).

- 1 2 "Species Profile: Canada Warbler". Species at Risk Public Registry. Government of Canada. May 29, 2014. Retrieved June 5, 2014.

- ↑ Byrd, Elon E.; Denton, Fred (August 1949). "The Helminth Parasites of Birds. II. A New Species of Acanthocephala from North American Birds". The Journal of Parasitology. 35 (4): 391–410. doi:10.2307/3273430. Retrieved December 15, 2016.

- ↑ USGS Paxtuxent Wildlife Research Center (2016). "Canada Warbler, Cardellina canadensis: North American Breeding Bird Survey Trend Results". U.S. Geological Survey. Department of Interior. Retrieved December 16, 2016.

- ↑ "Warbler, Canada". Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC). Government of Canada. November 11, 2011. Retrieved June 5, 2014.

General sources

- Bent, Arthur Cleveland (1953). "Canada Warbler". Life Histories of North American Wood Warblers: Order Passeriformes. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office. pp. 646–56. LCCN 53061305. Hosted online by HathiTrust.

- Conway, Courtney J. (1999). Canada Warbler (Wilsonia canadensis). The Birds of North America: Life Histories for the 21st Century (A. Poole, P. Stettenheim, and F. Gill, series editors). 421. Washington, D.C.: American Ornithologists' Union.

- Dunn, Jon J.; Garrett, Kimball L. (1997). A Field Guide to Warblers of North America. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co. ISBN 0395389712.

Further reading

Report

- Cooper JM, Enns KA & Shepard MG. (1997). Status of the Canada warbler in British Columbia. Canadian Research Index. p. n/a.

Thesis

- Kingsley AL. M.Sc. (1998). Response of birds and vegetation to the first cut of the uniform shelterwood silvicultural system in the white pine forests of Algonquin Provincial Park, Ontario. Trent University (Canada), Canada.

- Ramos Olmos MA. Ph.D. (1983). Seasonal Movements of Bird Populations at a Neotropical Study Site in Southern Veracruz, Mexic. University of Minnesota, United States—Minnesota.

Articles

- Barrowclough GF & Corbin KW. (1978). Genetic Variation and Differentiation in the Parulidae. Auk. vol 95, no 4. pp. 691–702.

- Caroline G, Marcel D, Jean-Pierre LS & Jean H. (2004). Are temperate mixedwood forests perceived by birds as a distinct forest type?. Canadian Journal of Forest Research. vol 34, no 9. p. 1895.

- Christian DP, Hanowski JM, Reuvers-House M, Niemi GJ, Blake JG & Berguson WE. (1996). Effects of mechanical strip thinning of aspen on small mammals and breeding birds in northern Minnesota, U.S.A. Canadian Journal of Forest Research. vol 26, no 7. pp. 1284–1294.

- Crawford HS & Jennings DT. (1989). Predation by Birds on Spruce Budworm Choristoneura-Fumiferana Functional Numerical and Total Responses. Ecology. vol 70, no 1. pp. 152–163.

- Dunn EH & Nol E. (1980). Age Related Migratory Behavior of Warblers. Journal of Field Ornithology. vol 51, no 3. pp. 254–269.

- Golet FC, Wang Y, Merrow JS & DeRagon WR. (2001). Relationship between habitat and landscape features and the avian community of red maple swamps in southern Rhode Island. Wilson Bulletin. vol 113, no 2. pp. 217–227.

- Hobson KA & Bayne E. (2000). The effects of stand age on avian communities in aspen-dominated forests of central Saskatchewan, Canada. Forest Ecology & Management. vol 136, no 1-3. pp. 121–134.

- Hobson KA & Schieck J. (1999). Changes in bird communities in boreal mixedwood forest: Harvest and wildfire effects over 30 years. Ecological Applications. vol 9, no 3. pp. 849–863.

- Jones SE. (1977). Coexistence in Mixed Species Antwren Flocks. Oikos. vol 29, no 2. pp. 366–375.

- Lacki MJ. (2000). Surveys of bird communities on Little Black and Black mountains: Implications for long-term conservation of Montane birds in Kentucky. Journal of the Kentucky Academy of Science. vol 61, no 1. pp. 50–59.

- Lebbin DJ. (2004). Unusual June record of Canada Warbler (Wilsonia canadensis) in Bolivar, Venezuela. Ornitologia Neotropical. vol 15, no 1. pp. 143–144.

- Merrill SB, Cuthbert FJ & Oehlert G. (1998). Residual patches and their contribution to forest-bird diversity on northern Minnesota aspen clearcuts. Conservation Biology. vol 12, no 1. pp. 190–199.

- Mitchell JM. (1999). Habitat relationships of five northern bird species breeding in hemlock ravines in Ohio, USA. Natural Areas Journal. vol 19, no 1. pp. 3–11.

- Morris SR, Richmond ME & Holmes DW. (1994). Patterns of stopover by warblers during spring and fall migration on Appledore Island, Maine. Wilson Bulletin. vol 106, no 4. pp. 703–718.

- Morse DH. (1977). The Occupation of Small Islands by Passerine Birds. Condor. vol 79, no 4. pp. 399–412.

- Patten MA & Burger JC. (1998). Spruce budworm outbreaks and the incidence of vagrancy in eastern North American wood-warblers. Canadian Journal of Zoology. vol 76, no 3. pp. 433–439.

- Prins TG & Debrot AO. (1996). First record of the Canada Warbler for Bonaire, Netherlands Antilles. Caribbean Journal of Science. vol 32, no 2. pp. 248–249.

- Rappole JH. (1983). ANALYSIS OF PLUMAGE VARIATION IN THE CANADA WARBLER. Journal of Field Ornithology. vol 54, no 2. pp. 152–159.

- Robinson SK, Fitzpatrick JW & Terborgh J. (1995). Distribution and habitat use of neotropical migrant landbirds in the Amazon basin and Andes. Bird Conservation International. vol 5, no 2-3. pp. 305–323.

- Sabo SR & Whittaker RH. (1979). Bird Niches in a Subalpine Forest an Indirect Ordination. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. vol 76, no 3. pp. 1338–1342.

- Skinner C. (2003). A breeding bird survey of the natural areas at Holden Arboretum. Ohio Journal of Science. vol 103, no 4. pp. 98–110.

- Sodhi NS & Paszkowski CA. (1995). Habitat use and foraging behavior of four parulid warblers in a second-growth forest. Journal of Field Ornithology. vol 66, no 2. pp. 277–288.

- Weakland CA, Wood PB & Ford WM. (2002). Responses of songbirds to diameter-limit cutting in the central Appalachians of West Virginia, USA. Forest Ecology and Management. vol 155, no 1-3. pp. 115–129.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cardellina canadensis. |

| Wikispecies has information related to: Cardellina canadensis |

- "Canada warbler media". Internet Bird Collection.

- Canada warbler Species Account - Cornell Lab of Ornithology

- Canada warbler - Wilsonia canadensis - USGS Patuxent Bird Identification InfoCenter

- Canada warbler photo gallery at VIREO (Drexel University)