William Walton

Sir William Turner Walton, OM (29 March 1902 – 8 March 1983) was an English composer. During a sixty-year career, he wrote music in several classical genres and styles, from film scores to opera. His best-known works include Façade, the cantata Belshazzar's Feast, the Viola Concerto and the First Symphony.

Born in Oldham, Lancashire, the son of a musician, Walton was a chorister and then an undergraduate at Christ Church, Oxford. On leaving the university, he was taken up by the literary Sitwell siblings, who provided him with a home and a cultural education. His earliest work of note was a collaboration with Edith Sitwell, Façade, which at first brought him notoriety as a modernist, but later became a popular ballet score.

In middle age, Walton left Britain and set up home with his young wife Susana on the Italian island of Ischia. By this time, he had ceased to be regarded as a modernist, and some of his compositions of the 1950s were criticised as old-fashioned. His only full-length opera, Troilus and Cressida, was among the works to be so labelled and has made little impact in opera houses. In his last years, his works came back into critical fashion; his later compositions, dismissed by critics at the time of their premieres, were revalued and regarded alongside his earlier works.

Walton was a slow worker, painstakingly perfectionist, and his complete body of work across his long career is not large. His most popular compositions continue to be frequently performed in the twenty-first century, and by 2010 almost all his works had been released on CD.

Biography

Early years

.jpg)

Walton was born into a musical family in Oldham, Lancashire, the second son in a family of three boys and a girl. His father, Charles Alexander Walton, was a musician who had trained at the Royal Manchester College of Music under Charles Hallé, and made a living as a singing teacher and church organist. Charles's wife, Louisa Maria (née Turner), had been a singer before their marriage.[1] William Walton's musical talents were spotted when he was still a young boy, and he took piano and violin lessons, though he never mastered either instrument. He was more successful as a singer:[2] he and his elder brother sang in their father's choir, taking part in performances of large-scale works by Handel, Haydn, Mendelssohn and others.[3] Walton was sent to a local school, but in 1912 his father saw a newspaper advertisement for probationer choristers at Christ Church Cathedral School in Oxford and applied for William to be admitted. The boy and his mother missed their intended train from Manchester to Oxford because Walton's father had spent the money for the fare in a local public house.[4] Louisa Walton had to borrow the fares from a greengrocer.[4] Although they arrived in Oxford after the entrance trials were over, Mrs Walton successfully pleaded for her son to be heard, and he was accepted. He remained at the choir school for the next six years.[4] The Dean of Christ Church, Dr Thomas Strong, noted the young Walton's musical potential and was encouraged in this view by Sir Hubert Parry, who saw the manuscripts of some of Walton's early compositions and said to Strong, "There's a lot in this chap; you must keep your eye on him."[5]

At the age of sixteen Walton became an undergraduate of Christ Church. It is sometimes said that he was Oxford's youngest undergraduate since Henry VIII,[6] and though this is probably not correct, he was nonetheless among the youngest.[7] He came under the influence of Hugh Allen, the dominant figure in Oxford's musical life. Allen introduced Walton to modern music, including Stravinsky's Petrushka, and enthused him with "the mysteries of the orchestra".[8] Walton spent much time in the university library, studying scores by Stravinsky, Debussy, Sibelius, Roussel and others. He neglected his non-musical studies, and though he passed the musical examinations with ease, he failed the Greek and algebra examinations required for graduation.[9] Little survives from Walton's juvenilia, but the choral anthem A Litany, written when he was fifteen, anticipates his mature style.[10]

At Oxford Walton befriended several poets including Roy Campbell, Siegfried Sassoon and, most importantly for his future, Sacheverell Sitwell. Walton was sent down from Oxford in 1920 without a degree or any firm plans.[11] Sitwell invited him to lodge in London with him and his literary brother and sister, Osbert and Edith. Walton took up residence in the attic of their house in Chelsea, later recalling, "I went for a few weeks and stayed about fifteen years".[12]

First successes

The Sitwells looked after their protégé both materially and culturally, giving him not only a home but a stimulating cultural education. He took music lessons with Ernest Ansermet, Ferruccio Busoni and Edward J. Dent.[13] He attended the Russian ballet, met Stravinsky and Gershwin, heard the Savoy Orpheans at the Savoy Hotel and wrote an experimental string quartet heavily influenced by the Second Viennese School that was performed at a festival of new music at Salzburg in 1923.[10] Alban Berg heard the performance and was impressed enough to take Walton to meet Arnold Schoenberg, Berg's teacher and the founder of the Second Viennese School.[14]

In 1923, in collaboration with Edith Sitwell, Walton had his first great success, though at first it was a succès de scandale.[4] Façade was first performed in public at the Aeolian Hall, London, on 12 June.[n 1] The work consisted of Edith's verses, which she recited through a megaphone from behind a screen, while Walton conducted an ensemble of six players in his accompanying music.[4] The press was generally condemnatory. Walton's biographer Michael Kennedy cites as typical a contemporary headline: "Drivel That They Paid to Hear".[4] The Daily Express loathed the work, but admitted that it was naggingly memorable.[16] The Manchester Guardian wrote of "relentless cacophony".[17] The Observer condemned the verses and dismissed Walton's music as "harmless".[18] In The Illustrated London News, Dent was much more appreciative: "The audience was at first inclined to treat the whole thing as an absurd joke, but there is always a surprisingly serious element in Miss Sitwell's poetry and Mr Walton's music ... which soon induced the audience to listen with breathless attention."[19] In The Sunday Times, Ernest Newman said of Walton, "as a musical joker he is a jewel of the first water".[20] Among the audience were Evelyn Waugh, Virginia Woolf and Noël Coward. The last was so outraged by the avant-garde nature of Sitwell's verses and the staging, that he marched out ostentatiously during the performance.[21][n 2] The players did not like the music: the clarinettist, Charles Draper asked the composer, "Mr Walton, has a clarinet player ever done you an injury?"[22] Nevertheless, the work soon became accepted, and within a decade Walton's music was used for the popular Façade ballet, choreographed by Frederick Ashton.[23]

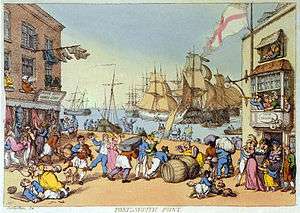

Walton's works of the 1920s, while he was living in the Sitwells' attic, include the overture Portsmouth Point, dedicated to Sassoon and inspired by the well-known painting of the same name by Thomas Rowlandson. It was first heard as an entr'acte at a performance in Diaghilev's 1926 ballet season, where The Times complained, "It is a little difficult to make much of new music when it is heard through the hum of conversation."[24] Sir Henry Wood programmed the work at the Proms the following year, where it made more of an impression.[25] The composer conducted this performance; he did not enjoy conducting, but he had firm views on how his works should be interpreted, and orchestral players appreciated his "easy nonchalance" and "complete absence of fuss."[26] Walton's other works of the 1920s included a short orchestral piece, Siesta (1926) and a Sinfonia Concertante for piano and orchestra (1928), which was well received at its premiere at a Royal Philharmonic Society concert, but has not entered the regular repertory.[27]

The Viola Concerto (1929) brought Walton to the forefront of British classical music. It was written at the suggestion of Sir Thomas Beecham for the viola virtuoso Lionel Tertis. When Tertis received the manuscript, he rejected it immediately. The composer and violist Paul Hindemith stepped into the breach and gave the first performance.[28] The work was greeted with enthusiasm. In The Manchester Guardian, Eric Blom wrote, "This young composer is a born genius" and said that it was tempting to call the concerto the best thing in recent music of any nationality.[29] Tertis soon changed his mind and took the work up. A performance by him at a Three Choirs Festival concert in Worcester in 1932 was the only occasion on which Walton met Elgar, whom he greatly admired. Elgar did not share the general enthusiasm for Walton's concerto.[30][n 3]

Walton's next major composition was the massive choral cantata Belshazzar's Feast (1931). It began as a work on a modest scale; the BBC commissioned a piece for small chorus, orchestra of no more than fifteen players, and soloist.[32] Osbert Sitwell constructed a text, selecting verses from several books of the Old Testament and the Book of Revelation. As Walton worked on it, he found that his music required far larger forces than the BBC proposed to allow, and Beecham rescued him by programming the work for the 1931 Leeds Festival, to be conducted by Malcolm Sargent. Walton later recalled Beecham as saying, "As you'll never hear the work again, my boy, why not throw in a couple of brass bands?"[33][n 4] During early rehearsals, the Leeds chorus members found Walton's music difficult to master, and it was falsely rumoured in London musical circles that Beecham had been obliged to send Sargent to Leeds to quell a revolt.[34][n 5] The first performance was a triumph for the composer, conductor and performers.[36] A contemporary critic wrote, "Those who experienced the tremendous impact of its first performance had full justification for feeling that a great composer had arisen in our land, a composer to whose potentialities it was impossible to set any limits."[37] The work has remained a staple of the choral repertoire.[10]

1930s

In the 1930s, Walton's relationship with the Sitwells became less close. He had love affairs and new friendships that drew him out of their orbit.[4] His first long affair was with Imma von Doernberg, the young widow of a German baron. She and Walton met in the late 1920s and they were together until 1934, when she left him.[38] His later affair with Alice, Viscountess Wimborne (born 1880), which lasted from 1934 until her death in April 1948, caused a wider breach between Walton and the Sitwells, as she disliked them as much as they disliked her.[39][n 6] By the 1930s, Walton was earning enough from composing to allow him financial independence for the first time. A legacy from a musical benefactress in 1931 further enhanced his finances, and in 1934 he left the Sitwells' house and bought a house in Belgravia.[39]

Walton's first major composition after Belshazzar's Feast was his First Symphony. It was not written to a commission, and Walton worked slowly on the score from late 1931 until he completed it in 1935. He had composed the first three of the four movements by the end of 1933 and promised the premiere to the conductor Hamilton Harty. Walton then found himself unable to complete the work. The end of his affair with Imma von Doernberg coincided with, and may have contributed to, a sudden and persistent writer's block.[2] Harty persuaded Walton to let him perform the three existing movements, which he premiered in December 1934 with the London Symphony Orchestra.[10] During 1934 Walton interrupted work on the symphony to compose his first film music, for Paul Czinner's Escape Me Never (1934), for which he was paid £300.[40][n 7] After a break of eight months, Walton resumed work on the symphony and completed it in 1935. Harty and the BBC Symphony Orchestra gave the premiere of the completed piece in November of that year.[n 8] The symphony aroused international interest. The leading continental conductors Wilhelm Furtwängler and Willem Mengelberg sent for copies of the score, the Chicago Symphony Orchestra premiered the work in the US under Harty, Eugene Ormandy and the Philadelphia Orchestra gave the New York premiere, and the young George Szell conducted the symphony in Australia.[43][n 9]

Elgar having died in 1934, the authorities turned to Walton to compose a march in the Elgarian tradition for the coronation of George VI in 1937. His Crown Imperial was an immediate success with the public, but disappointed those of Walton's admirers who thought of him as an avant garde composer.[n 10] Among Walton's other works from this decade are more film scores, including the first of his incidental music for Shakespeare adaptations, As You Like It (1936); a short ballet for a West End revue (1936); and a choral piece, In Honour of the City of London (1937). His most important work of the 1930s, alongside the symphony, was the Violin Concerto (1939), commissioned by Jascha Heifetz. The concerto, Walton later revealed, expressed his love for Alice Wimborne.[46] Its strong romantic style caused some critics to label it retrogressive,[47] and Walton said in a newspaper interview, "Today's white hope is tomorrow's black sheep. These days it is very sad for a composer to grow old ... I seriously advise all sensitive composers to die at the age of 37. I know: I've gone through the first halcyon period and am just about ripe for my critical damnation."[48]

In the late 1930s Walton became aware of a younger English composer whose fame was shortly to overtake his, Benjamin Britten.[2] After their first meeting, Britten wrote in his diary, "[...] to lunch with William Walton at Sloane Square. He is charming, but I feel always the school relationship with him – he is so obviously the head prefect of English music, whereas I'm the promising new boy."[49] They remained on friendly terms for the rest of Britten's life; Walton admired many of Britten's works, and considered him a genius; Britten did not admire all of Walton's works but was grateful for his support at difficult times in his life.[10][50][n 11]

Second World War

During the Second World War Walton was exempted from military service on the understanding that he would compose music for wartime propaganda films. In addition to driving ambulances (extremely badly, he said),[51] he was attached to the Army Film Unit as music adviser. He wrote scores for six films during the war – some that he thought "rather boring" and some that have become classics such as The First of the Few (1942) and Laurence Olivier's adaptation of Shakespeare's Henry V (1944).[10] Walton was at first dismissive of his film scores, regarding them as professional but of no intrinsic worth; he resisted attempts to arrange them into concert suites, saying, "Film music is not good film music if it can be used for any other purpose." He later relented to the extent of allowing concert suites to be arranged from The First of the Few and the Olivier Shakespeare films.[52] For the BBC, Walton composed the music for a large-scale radio drama about Christopher Columbus, written by Louis MacNeice and starring Olivier. As with his film music, the composer was inclined to dismiss the musical importance of his work on the programme.[53] Apart from these commissions, Walton's wartime works of any magnitude comprised incidental music for John Gielgud's 1942 production of Macbeth; two scores for the Sadler's Wells Ballet, The Wise Virgins, based on the music of J. S. Bach transcribed by Walton, and The Quest, with a plot loosely based on Spenser's The Faerie Queene;[4] and, for the concert hall, a suite of orchestral miniatures, Music for Children,[54] and a comedy overture, Scapino, composed for the fiftieth anniversary of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra.[10]

Walton's house in London was destroyed by German bombing in May 1941, after which he spent much of his time at Alice Wimborne's family house at Ashby St Ledgers in the countryside of Northamptonshire in the middle of England. While there, Walton worked on projects that had been in his mind for some time. In 1939 he had been planning a substantial chamber work, a string quartet, but he set it aside while composing his wartime film scores. In early 1945 he turned again to the quartet. Walton was conscious that Britten, with Les Illuminations (1940), the Sinfonia da Requiem (1942), and Peter Grimes in 1945, had produced a series of substantial works, while Walton had produced no major composition since the Violin Concerto in 1939.[55] Among English critics and audiences, the Violin Concerto was not at first rated one of Walton's finest works. Because Heifetz had bought the exclusive rights to play the concerto for two years, it was not heard in Britain until 1941. The London premiere, with a less famous soloist, and in the unflattering acoustics of the Royal Albert Hall, did not immediately reveal the work as a masterpiece.[56] The String Quartet in A minor, premiered in May 1947, was Walton's most substantial work of the 1940s. His biographer, Michael Kennedy, calls it one of his finest achievements and "a sure sign that he had thrown off the trammels of his cinema style and rediscovered his true voice."[57]

Post-war

In 1947, Walton was presented with the Royal Philharmonic Society's Gold Medal.[58] In the same year he accepted an invitation from the BBC to compose his first opera.[58] He decided to base it on Chaucer's Troilus and Criseyde, but his preliminary work came to a halt in April 1948 when Alice Wimborne died. To take Walton's mind off his grief, the music publisher Leslie Boosey persuaded him to be a British delegate to a conference on copyright in Buenos Aires later that year. [n 12] While there, Walton met Susana Gil Passo (1926–2010), daughter of an Argentine lawyer. At 22 she was 24 years younger than Walton (Alice Wimborne had been 22 years his senior), and at first she ridiculed his romantic interest in her. He persisted, and she eventually accepted his proposal of marriage. The wedding was held in Buenos Aires in December 1948. From the start of their marriage, the couple spent half the year on the Italian island of Ischia, and by the mid-1950s they lived there permanently.[60]

Walton's last work of the 1940s was his music for Olivier's film of Hamlet (1948). After that, he focused his attentions on his opera Troilus and Cressida. On the advice of the BBC, he invited Christopher Hassall to write the libretto. This did not help Walton's relations with the Sitwells, each of whom thought he or she should have been asked to be his librettist.[61] Work continued slowly over the next few years, with many breaks while Walton turned to other things. In 1950 he and Heifetz recorded the Violin Concerto for EMI. In 1951 Walton was knighted. In the same year, he prepared an authorised version of Façade, which had undergone many revisions since its premiere. In 1953, following the accession of Elizabeth II he was again called on to write a coronation march, Orb and Sceptre; he was also commissioned to write a choral setting of the Te Deum for the occasion.[62]

Troilus and Cressida was presented at Covent Garden on 3 December 1954. Its preparation was dogged by misfortunes. Olivier, originally scheduled to direct it, backed out, as did Henry Moore who had agreed to design the production; Elisabeth Schwarzkopf, for whom the role of Cressida had been written, refused to perform it; her replacement, Magda László, had difficulty mastering the English words; and Sargent, the conductor, "did not seem well acquainted with the score".[63][64] The premiere had a friendly reception, but there was a general feeling that Hassall and Walton had written an old-fashioned opera in an outmoded tradition.[65] The piece was subsequently staged in San Francisco, New York and Milan during the next year, but failed to make a positive impression, and did not enter the regular operatic repertory.[66]

In 1956 Walton sold his London house and took up full-time residence on Ischia. He built a hilltop house at Forio and called it La Mortella. Susana Walton created a magnificent garden there.[67] Walton's other works of the 1950s include the music for a fourth Shakespeare film, Olivier's Richard III, and the Cello Concerto (1956), written for Gregor Piatigorsky, who gave the premiere in January 1957 with the Boston Symphony Orchestra and the conductor Charles Munch. Some critics felt that the concerto was old-fashioned; Peter Heyworth wrote that there was little in the work that would have startled an audience in the year the Titanic met its iceberg (1912).[68] It has nevertheless entered the regular repertoire, performed by Paul Tortelier, Yo-Yo Ma, Lynn Harrell and Pierre Fournier among others. [n 13]

In 1966 Walton successfully underwent surgery for lung cancer.[70] Until then he had been an inveterate pipe-smoker, but after the operation he never smoked again.[71] While he was convalescing, he worked on a one-act comic opera, The Bear, which was premiered at Britten's Aldeburgh Festival, in June 1966, and enthusiastically received. Walton had become so used to being written off by music critics that he felt "there must be something wrong when the worms turned on some praise."[72] Walton received the Order of Merit in 1967,[73] the fourth composer to be so honoured, after Elgar, Vaughan Williams and Britten.[9]

Walton's orchestral works of the 1960s include his Second Symphony (1960), Variations on a Theme by Hindemith (1963), Capriccio burlesco (1968), and Improvisations on an Impromptu of Benjamin Britten (1969). His song cycles from this period were composed for Peter Pears (Anon. in Love, 1960) and Schwarzkopf (A Song for the Lord Mayor's Table, 1962). He was commissioned to compose a score for the 1969 film Battle of Britain, but the film company rejected most of his score, replacing it with music by Ron Goodwin. A concert suite of Walton's score was published and recorded after Walton's death.[74] After his experience over Battle of Britain, Walton declared that he would write no more film music, but he was persuaded by Olivier to compose the score for a film of Chekhov's Three Sisters in 1969.[75]

Last years

Walton was never a facile or quick composer, and in his final decade, he found composition increasingly difficult. He repeatedly tried to compose a third symphony for André Previn, but eventually abandoned it.[76][n 14] Many of his final works are re-orchestrations or revisions of earlier music. He orchestrated his song cycle Anon. in Love (originally for tenor and guitar), and at the request of Neville Marriner adapted his A minor String Quartet as a Sonata for Strings.[77] One original work from this period was his Jubilate Deo, premiered as one of several events to celebrate his seventieth birthday. The British prime minister, Edward Heath, gave a birthday dinner for Walton at 10 Downing Street, attended by royalty and Walton's most eminent colleagues; Britten presented a Walton evening at Aldeburgh and Previn conducted an all-Walton concert at the Royal Festival Hall.[78][79]

Walton revised the score of Troilus and Cressida, and the opera was staged at Covent Garden in 1976. Once again it was plagued by misfortune while in preparation. Walton was in poor health; Previn, who was to conduct, also fell ill; and the tenor chosen for Troilus pulled out. As in 1954, the critics were generally tepid.[80] Some of Walton's final artistic endeavours were in collaboration with the film-maker Tony Palmer. Walton took part in Palmer's profile of him, At the Haunted End of the Day, in 1981, and in 1982 Walton and his wife played the cameo roles of King Frederick Augustus and Queen Maria of Saxony in Palmer's nine-hour film Wagner.[81]

Walton died at La Mortella on 8 March 1983, at the age of 80.[6] His ashes were buried on Ischia, and a memorial service was held at Westminster Abbey, where a commemorative stone to Walton was unveiled near those to Elgar, Vaughan Williams and Britten.[82]

Legacy

In 1944, it was said of Walton that he summed up the recent past of English music and augured its future.[83] Later writers have concluded that Walton had little influence on the next generation of composers.[n 15] In his later years, Walton formed friendships with younger composers including Hans Werner Henze and Malcolm Arnold, but although he admired their work, he did not influence their compositional styles.[n 16] Throughout his life, Walton held no posts at music conservatoires; he had no pupils, gave no lectures and wrote no essays.[87] After his death, the Walton Trust, inspired by Susana Walton, has run arts education projects, promoted British music and held annual summer masterclasses on Ischia for gifted young musicians.[88][89]

Music

Walton was a slow worker. Both during composition and afterwards he would continually revise his music; he said, "Without an india-rubber I was absolutely sunk."[90] Consequently, his total body of work from his sixty-year career as a composer is not large. Between the first performance of Façade in 1923, for example, and that of the Sinfonia Concertante in 1928, he averaged only one small piece a year.[91] Of his work as a whole, Byron Adams in Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians writes:

Walton's music has often been too neatly dismissed by a few descriptive tags: "bittersweet", "nostalgic" and, after World War II, "same as before". Such convenient categorizations ignore the expressive variety of his music and slight his determination to deepen his technical and expressive resources as he grew older. His early discovery of the basic elements of his style allowed him to assimilate successfully an astonishing number of disparate and apparently contradictory influences, such as Anglican anthems, jazz, and the music of Stravinsky, Sibelius, Ravel and Elgar.[10]

The writer adds that Walton's allegiance to his basic style never wavered and that this loyalty to his own vision, together with his rhythmic vitality, sensuous melancholy, sly charm and orchestral flair, gives Walton's finest music "an imperishable glamour".[10] Another biographer of Walton, Neil Tierney, writes that although contemporary critics felt that the post-war music did not match Walton's pre-war compositions, it has become clear that the later works are "if emotionally less direct, more profound."[91]

Orchestral music

Overtures and short orchestral pieces

Walton's first work for full orchestra, Portsmouth Point (1925), inspired by a Rowlandson print of the same name, depicts a rumbustious dockside scene (in Kennedy's phrase, "the sailors of H.M.S. Pinafore have had a night on the tiles") in a fast moving score full of syncopation and cross-rhythm that for years proved hazardous for conductors and orchestras alike.[92] Throughout his career, Walton wrote works in this pattern, such as the lively Comedy Overture Scapino, a virtuoso piece commissioned by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, described by The Musical Times as "an ingenious blending of fragments in exhilarating profusion."[93] Walton's post-war works in this genre are the Johannesburg Festival Overture (1956), the "diverting but hard-edged Capriccio burlesco" (1968),[10] and the longer Partita (1957), written for the Cleveland Orchestra, described by Grove as "an impressively concentrated score with a high-spirited finale [with] steely counterpoint and orchestral virtuosity".[10] Walton's shorter pieces also include two tributes to musical colleagues, Variations on a Theme by Hindemith (1963) and the Improvisations on an Impromptu of Benjamin Britten (1969), in both of which the source material is gradually transformed as Walton's own voice becomes more prominent.[10] The critic Hugh Ottaway commented that in both pieces "the interaction of two musical personalities is ... fascinating".[94]

Concertos and symphonies

Walton's first successful large-scale concert work, the Viola Concerto (1929) is in marked contrast to the raucous Portsmouth Point; despite the common influence of jazz and of the music of Hindemith and Ravel, in its structure and romantic longing it owes much to the Elgar Cello Concerto.[9] In this work, wrote Edward Sackville-West and Desmond Shawe-Taylor in The Record Guide, "the lyric poet in Walton, who had so far been hidden under a mask of irony, fully emerged."[95] Walton followed this pattern in his two subsequent concertos, for Violin (1937) and for Cello (1956). Each opens reflectively, is in three movements, and contrasts agitated and jagged passages with warmer romantic sections.[10] The Cello Concerto is more introspective than the two earlier concertos, with a ticking rhythm throughout the work suggesting the inexorable passage of time.[10]

The two symphonies are strongly contrasted with one another. The First is on a large scale, reminiscent at times of Sibelius.[96] Grove says of the work that its "orgiastic power, coruscating malice, sensuous desolation and extroverted swagger" make the symphony a tribute to Walton's tenacity and inventive facility.[10] Critics have always differed on whether the finale lives up to the rest of the work.[93][97] In comparison with the First, the Second Symphony struck many reviewers as lightweight, and, as with many of Walton's works of the 1950s, it was regarded as old fashioned. It is a very different kind of work from the First Symphony. David Cox describes it as "more a divertimento than a symphony ... highly personal, unmistakably Walton throughout",[98] and Kennedy calls it "somewhat enigmatic in mood, and a superb example of Walton's more mature, concise, and mellow post-1945 style."[4]

Music for ballets, plays and films

Although generally a slow and perfectionist composer, Walton was capable of working quickly when necessary. Some of his stage and screen music was written to tight deadlines. He regarded his ballet and incidental music as of less importance than his concert works and was generally dismissive of what he produced. Of his ballets for Sadler's Wells, The Wise Virgins (1940) is an arrangement of eight extracts from choral and instrumental music by Bach.[n 17] The Quest (1943), written in great haste, is, according to Grove, oddly reminiscent of Vaughan Williams.[10] Neither of these works established itself in the regular repertoire, unlike the ballet score Walton arranged from the music of Façade, the music for which was expanded for full orchestra, still retaining the jazz influences and the iconoclastic wit of the original.[9] Music from The Quest and the whole of the Viola Concerto were used for another Sadler's Wells ballet, O.W., in 1972.[100]

Walton wrote little incidental music for the theatre, his music for Macbeth (1942) being one of his most notable contributions to the genre. For the cinema he wrote the music for 13 films between 1934 and 1969. He arranged the Spitfire Prelude and Fugue from his own score for The First of the Few (1942), and he allowed suites to be arranged from his Shakespeare film scores of the 1940s and 1950s. In these films, Walton mixed Elizabethan pastiche with wholly characteristic Waltonian music. Kennedy singles out for praise the Agincourt battle sequence in Henry V, where Walton's music makes the charge of the French knights "fearsomely real."[4] Despite Walton's view that film music is ineffective when performed out of context, suites from several more of his film scores have been put together since his death.[10]

Opera

Walton worked for many years on his only full-length opera, Troilus and Cressida, both before its premiere and afterwards. It has never been regarded as a success. The libretto is generally considered weak, and Walton's music, despite many passages that have won critical praise, is not dramatic enough to sustain interest.[4] Grove calls the work a partially successful attempt to revivify the traditions of nineteenth-century Italian opera in a post-war era wary of heroic Romanticism.[10]

Walton's only other opera, The Bear, based on a comic vaudeville by Chekhov, is judged by critics as much more successful. It is, however, a one-act piece, a genre not regularly staged at most opera houses,[101] and so is infrequently seen. Operabase records four productions of the piece worldwide between 2013 and 2015.[102]

Chamber works

Apart from an early experiment in atonalism in his String Quartet (1919–22), which he later described as "full of undigested Bartók and Schoenberg", Walton's major essays in chamber music are his String Quartet in A Minor (1945–46) and the Sonata for Violin and Piano (1947–49). In the opinion of Adams in Grove's Dictionary, the quartet is one of Walton's supreme achievements. Earlier critics did not always share this view. In 1956 The Record Guide said, "[T]he material is not first class and the composition as a whole seems laboured."[103] The work exists also in its later expanded form as the Sonata for Strings (1971), which, the critic Trevor Harvey wrote, combines Walton in his most energetically rhythmic mood with a "vein of lyrical tenderness which is equally characteristic and is so rewarding to listen to".[104] The Violin Sonata is in two closely related movements, with strong thematic material in common. The first movement is nostalgically lyrical, the second a set of variations, each one a semitone higher than its predecessor.[105] Walton briefly refers back to Schoenberg with a dodecaphonic passage in the second movement, but otherwise the sonata is firmly tonal.[10]

Choral and other vocal music

Walton's liturgical compositions include the Coronation Te Deum (1952), Missa brevis (1966), Jubilate Deo (1972), and Magnificat and Nunc dimittis (1974), and the anthems A Litany (1916) and Set me as a seal upon thy heart (1938).[106]

One of the best-known and most frequently performed of Walton's works is the cantata Belshazzar's Feast.[107] Written for large orchestra, chorus and baritone soloist, it intersperses a choral and orchestral depiction of Babylonian excess and depravity, barbaric jazzy outbursts, and the lamentations and finally the rejoicing of the Jewish captives. The "couple of brass bands" added at Beecham's suggestion to an already large orchestra each consist of three trumpets, three trombones and a tuba.[108] Many critics judged it the most important English choral work since Elgar's The Dream of Gerontius in 1900.[4] None of Walton's later choral works have matched its popularity. They include In Honour of the City of London (1937) and a Gloria (1960–61) composed for the 125th anniversary of the Huddersfield Choral Society.[10]

Recordings

From the days of 78 rpm discs, when relatively little modern music was being put on record, Walton was favoured by the record companies.[109] In 1929 the small, new Decca company recorded eleven movements from Façade, with the composer conducting a chamber ensemble, with the speakers Edith Sitwell and Walton's friend and colleague Constant Lambert.[n 18] In the 1930s, Walton also had two of his major orchestral works on disc, both on Decca, the First Symphony recorded by Harty and the London Symphony Orchestra, and the Viola Concerto with Frederick Riddle and the LSO conducted by the composer.[109] In the 1940s Walton moved from Decca to its older, larger rival, EMI. The EMI producer Walter Legge arranged a series of recordings of Walton's major works and many minor ones over the next twenty years; a rival composer expressed the view that if Walton had an attack of flatulence (he used an earthier expression), Walter Legge would record it.[111]

Walton himself, although a reluctant conductor, conducted many of the EMI recordings, and some for other labels. He made studio recordings of the First Symphony,[112] the Viola Concerto,[113] the Violin Concerto,[114] the Sinfonia Concertante,[115] the Façade Suites,[116] the Partita,[117] Belshazzar's Feast,[118] and suites from his film scores for Shakespeare plays and The First of the Few.[119] Some live performances conducted by Walton were recorded and have been released on compact disc, including the Cello Concerto[120] and the Coronation Te Deum.[121]

Almost all Walton's works have been recorded for commercial release.[122] EMI published a "Walton Edition" of his major works on CD in the 1990s, and the recording of the Chandos Records "Walton Edition" of his works was completed in 2010.[122][123] His best-known works have been recorded by performers from many countries.[111] Among the frequently recorded are Belshazzar's Feast, the Viola and Violin Concertos and the First Symphony, which has had more than twenty recordings since Harty's 1936 set.[124]

Notes, references and sources

Notes

- ↑ There had been private performances of Façade the previous year.[15]

- ↑ Soon afterwards Coward wrote a revue sketch lampooning the Sitwells, which caused a feud between him and them that lasted for decades.[21]

- ↑ Tertis had premiered Elgar's own "Viola Concerto" two years earlier – an arrangement of the Cello Concerto for solo viola and orchestra.[31]

- ↑ These large extra brass forces were already available at the festival, as Beecham had scheduled performances there of Berlioz's extravagantly scored Requiem.[33]

- ↑ The author of a 2001 biography of Sargent, Richard Aldous, gives some credence to the story.[35]

- ↑ The Grove article on Walton wrongly gives her name as "Lady Alice Wimbourne".[10]

- ↑ In terms of average earnings this equates to £60,000 in 2009.[41]

- ↑ Contemporary press reports name the orchestra as the BBC Symphony, as does Kennedy.[42] Byron Adams in Grove's Dictionary names the orchestra as the LSO.[10]

- ↑ Furtwängler programmed the work but did not conduct it himself, assigning it to a guest conductor, Leo Borchard.[44]

- ↑ The Musical Times thought it "unrepresentative" and "unlikely to survive".[45]

- ↑ Britten was not among the admirers of the Symphony No 1, finding it "dull and depressing".[50]

- ↑ Other British delegates were Eric Coates and A. P. Herbert.[59]

- ↑ More than twelve recordings have been issued of the work since Piatigorsky's.[69]

- ↑ Surviving sketches are reproduced in Kennedy, plate 11.

- ↑ In The Musical Times in 1994, Arnold Whittall listed Mahler, Britten, Stravinsky and Berg, but not Walton, as major influences on British composers of the post-war generation.[84]

- ↑ Arnold listed the principal influences on him as Berlioz, Mahler, Sibelius, Bartók and jazz.[85] Walton is not mentioned in the Grove articles on Henze or Arnold.[86]

- ↑ Later in 1940 Walton further arranged the music into a six-movement suite.[99]

- ↑ Walton and Lambert were rivals and friends. Walton was godfather to Lambert's son Kit.[110]

References

- ↑ Kennedy, p. 5

- 1 2 3 Greenfield, Edward. "Behind the Façade – Walton on Walton", Gramophone, February 2002, p. 93

- ↑ Kennedy, p. 6

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Kennedy, Michael. "Walton, Sir William Turner (1902–1983)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edition, May 2008, retrieved 27 September 2010 (subscription required)

- ↑ Kennedy, p. 7

- 1 2 Obituary, The Times, 29 March 1982, p. 5

- ↑ Kennedy, p. 10

- ↑ Kennedy, p. 8

- 1 2 3 4 Griffiths, Paul, and Jeremy Dibble. "Walton, Sir William (Turner)", The Oxford Companion to Music, Oxford Music Online, retrieved 27 September 2010 (subscription required)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 Adams, Byron. "Walton, William," Grove Music Online, Oxford Music Online, retrieved 27 September 2010 (subscription required)

- ↑ Kennedy, p.11

- ↑ Kennedy, p.16

- ↑ Kennedy, p. 19

- ↑ Kennedy, p. 26

- ↑ Kennedy, p. 304

- ↑ "Poetry Through a Megaphone", The Daily Express, 13 June 1923, p. 7

- ↑ "Futuristic Music and Poetry", The Manchester Guardian, 13 June 1923, p. 3

- ↑ "Music of the Week", The Observer, 17 June 1923, p. 10

- ↑ "The World of Music", The Illustrated London News, 23 June 1923, p. 1122

- ↑ Kennedy, p. 31

- 1 2 Hoare, p. 120.

- ↑ Kennedy, p. 33

- ↑ Kennedy, p. 62

- ↑ "The Russian Ballet", The Times, 29 June 1926, p. 14

- ↑ "Promenade Concert", The Times, 13 September 1927, p. 14

- ↑ Shore, p. 145 and Kennedy, p. 44

- ↑ Kennedy, pp. 44–45

- ↑ Kennedy, pp. 47–50

- ↑ "A Fine British Concert", The Manchester Guardian, 22 August 1930, p. 5, reviewing the second London performance.

- ↑ Kennedy, p. 52

- ↑ "Elgar's Life and Career", The Musical Times, April 1934, p. 318 (subscription required)

- ↑ Kennedy, p. 53

- 1 2 Kennedy, p. 58

- ↑ Reid, p. 201

- ↑ Aldous, pp. 50–52

- ↑ Aldous, p. 52

- ↑ Hussey, p. 409

- ↑ Kennedy, pp. 49 and 74

- 1 2 Kennedy, p. 78

- ↑ Kennedy, p. 76

- ↑ Williamson, Samuel H. "Five Ways to Compute the Relative Value of a UK Pound Amount, 1830 to Present", MeasuringWorth, 2008

- ↑ Cardus, Neville, "William Walton's First Symphony", The Manchester Guardian, 7 November 1935, p. 10; "William Walton's Symphony", The Times, 7 November 1935, p. 12; and Kennedy, p. 81

- ↑ Kennedy, p. 86; Downes, Olin. "Ormandy Directs Walton Symphony", The New York Times, 17 October 1936, p. 20 (Chicago and New York premieres); "Georg Szell – New Work Presented", The Sydney Morning Herald, 11 July 1939, p. 13 (Sydney premiere)

- ↑ "British Music in Berlin," The Times, 10 May 1936, p. 14

- ↑ McNaught, W. "Crown Imperial", The Musical Times, August 1937, p. 710 (subscription required)

- ↑ Kennedy, p. 104

- ↑ Mason, pp. 147–148

- ↑ Gilbert, G. "Walton on Trends in Composition", The New York Times, 4 June 1939, p. X5

- ↑ Britten, Benjamin. Diary, quoted in Kennedy, p. 96

- 1 2 Kennedy, pp. 130, 152 and 226

- ↑ Moorhead, Caroline. "Beyond the façade – the reluctant Grand Old Man", The Times, 29 March 1982, p. 5

- ↑ Kennedy, pp. 117 and 126

- ↑ Kennedy, p. 120

- ↑ The Times, 18 February 1941, p. 6

- ↑ Kennedy, p. 130

- ↑ "The New Concerto", The Times, 7 November 1941, p. 6

- ↑ Kennedy, p. 135

- 1 2 Kennedy, p. 136

- ↑ Kennedy, p. 143

- ↑ Kennedy, pp. 75, 140, 143, 144 and 208

- ↑ Kennedy, p. 145

- ↑ Wilkinson, pp. 27–28

- ↑ Kennedy, pp. 174–180

- ↑ Reid, p. 383

- ↑ Kennedy, p. 181

- ↑ Kennedy, pp. 181–82

- ↑ Kennedy, pp. 208–209

- ↑ Heyworth, Peter. "Music of the Establishment", The Observer, 17 February 1957, p. 11.

- ↑ "Walton Cello Concerto" WorldCat, retrieved 4 April 2015

- ↑ The Times, 9 February 1966, p. 12

- ↑ Kennedy, p. 229

- ↑ Kennedy, p. 232

- ↑ "No. 44460". The London Gazette. 24 November 1967. p. 12859.

- ↑ Kennedy, p. 239

- ↑ Kennedy, p. 243

- ↑ Kennedy, p. 271

- ↑ Kennedy, pp. 244–248

- ↑ Kennedy, pp. 251–253

- ↑ The Times, 29 March 1972; and 19 July 1972, p. 11

- ↑ Kennedy, p. 188

- ↑ Walton, p. 229

- ↑ The Times, 21 July 1983, p. 12 and Kennedy, p. 278.

- ↑ Evans, Edwin. "Modern British Composers", The Musical Times, November 1944, p. 330

- ↑ Whittall, Arnold. "Thirty (More) Years On", The Musical Times, March 1994, pp. 143–147

- ↑ "Obituary, Sir Malcolm Arnold", The Daily Telegraph, 25 September 2006, p. 25

- ↑ Burton-Page, Piers, "Malcolm Arnold", and Palmer-Füchsel, Virginia, "Hans Werner Henze", Grove Music Online, retrieved 13 October 2010 (subscription required)

- ↑ Kennedy, passim

- ↑ The Times, 15 September 1984, p. 9

- ↑ "The William Walton Trust" William Walton Trust, retrieved 29 November 2015

- ↑ Kennedy, p. 279

- 1 2 Tierney, Neil. Walton, Sir William Turner, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography Archive, retrieved 30 September 2010 (subscription required)

- ↑ Hussey, p. 407; and Franks, Alan (1974), liner notes to EMI CD CDM 7 64723 2

- 1 2 Evans, Edwin. "William Walton", The Musical Times, December 1944, p. 368 (subscription required)

- ↑ Ottaway, Hugh. "Belshazzar's Feast; Improvisations on an Impromptu of Benjamin", The Musical Times, November 1972, p. 1095 (subscription required)

- ↑ Sackville-West and Shawe-Taylor, p. 848

- ↑ Cardus, Neville. "William Walton's First Symphony". The Manchester Guardian, 7 November 1935, p. 10

- ↑ Cox, p. 193

- ↑ Cox, p. 195

- ↑ Lloyd-Jones, David (2002), liner notes to Naxos CD 8.555868.

- ↑ Percival, John. "Finding the paradox of Oscar Wilde", The Times, 23 February 1972, p. 11

- ↑ White, p. 306

- ↑ "William Walton", Operabase, retrieved 4 April 2015

- ↑ Sackville-West and Shawe-Taylor, p. 851

- ↑ Harvey, Trevor. "Walton, Sonata for Strings", The Gramophone, October 1973, p. 69

- ↑ Fiske, Roger. "Walton, Violin Sonata", The Gramophone, June 1955, p. 39

- ↑ "Choral", William Walton Trust, retrieved 4 April 2015

- ↑ Strimple, p. 89

- ↑ Lucas, p. 200

- 1 2 Greenfield, Edward. "Sir William Walton (1902–1983)", Gramophone, May 1983, p. 18

- ↑ Lloyd, pp. 49 and 211

- 1 2 Greenfield, Edward. "The Music of William Walton", Gramophone, October 1994, p. 92

- ↑ Recorded 1951, CD catalogue number EMI Classics 5 65004 2

- ↑ With Frederick Riddle (1937), CD catalogue number Pearl GEM 0171, William Primrose (1946), CD catalogue number Avid Classic AMSC 604, and Yehudi Menuhin (1968), CD catalogue number EMI Classics 5 65005 2

- ↑ With Heifetz (1950) CD catalogue number RCA Victor Gold Seal GD87966, and Menuhin (1969) CD catalogue number EMI CHS5 65003-2

- ↑ With Peter Katin (1970) CD catalogue number Lyrita SRCD 224

- ↑ (1936–38) CD catalogue number EMI Classics 7 63381 2

- ↑ CD catalogue number EMI Classics 65006

- ↑ 1943, CD catalogue number EMI Classics 7 63381 2; and 1959, CD catalogue number EMI Classics 5 65004 2

- ↑ 1963, CD catalogue number EMI Classics 5 65007 2

- ↑ With Pierre Fournier (1959), CD catalogue number BBC Legends 4098-2

- ↑ 1966, CD catalogue number BBC Legends 4098-2

- 1 2 Zuckerman, Paul S. "Introduction", William Walton Trust, retrieved 13 September 2010

- ↑ Greenfield, Edward. "Critics' Choice", Gramophone, December 1994, p. 52

- ↑ "Discography, William Walton Trust, retrieved 4 April 2015

Sources

- Aldous, Richard (2001). Tunes of glory: The life of Malcolm Sargent. London: Hutchinson. ISBN 978-0-09-180131-1.

- Cox, David (1967). "William Walton". In Simpson, Robert. The Symphony: Elgar to the Present Day. London: Pelican. OCLC 221594461.

- Hoare, Philip (1995). Noël Coward. London: Sinclair Stevenson. ISBN 978-1-85619-265-1.

- Hussey, Dyneley (1957). "William Walton". In Bacharach, A L. The Music Masters. London: Pelican Books. OCLC 655768838.

- Kennedy, Michael (1989). Portrait of Walton. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-816705-1.

- Lloyd, Stephen (2014). Constant Lambert: Beyond the Rio Grande. Woodbridge: : Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-898-2.

- Lucas, John (2008). Thomas Beecham. Woodbridge: Boydell. ISBN 978-1-84383-402-1.

- Mason, Colin (1946). "William Walton". In Bacharach, A L. British Music of Our Time. London: Pelican. OCLC 458571770.

- Reid, Charles (1968). Malcolm Sargent: a biography. Hamish Hamilton. ISBN 978-0-241-91316-1.

- Sackville-West, Edward; Shawe-Taylor, Desmond (1956). The Record Guide. London: Collins. OCLC 500373060.

- Shore, Bernard (1938). The Orchestra Speaks. London: Longmans. OCLC 499119110.

- Strimple, Nick (2002). Choral music in the Twentieth Century. Portland, US: Amadeus Press. ISBN 978-1-57467-122-3.

- Walton, Susana (1989). William Walton: Behind the Façade. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-282635-0.

- White, Eric Walter (1984) [1966]. Stravinsky: The Composer and his Works (second ed.). Berkeley, US: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-03985-8.

- Wilkinson, James (2011). The Queen's Coronation: The Inside Story. Scala. ISBN 978-1-85759-735-6.

Further reading

- Burton, Humphrey; Murray, Maureen (2002). William Walton: The Romantic Loner. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-816235-3.

- Craggs, Stewart R (1990). William Walton: A Catalogue. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-315474-2.

- Hayes, Malcolm, ed (2002). The Selected Letters of William Walton. London: Faber and Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-20105-1.

- Howes, Frank (1965). The Music of William Walton. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-315412-4.

- Lloyd, Stephen (2002). William Walton: Muse of Fire. Woodbridge: Boydell. ISBN 978-0-85115-803-7.

- Petrocelli, Paolo (2010). The Resonance of a Small Voice: William Walton and the Violin Concerto in England between 1900 and 1940. Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4438-1721-9.

External links

- William Walton Trust

- William Walton Online Archive. Archive of digitised works from the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

- Walton pages at Oxford University Press

- Sir William Turner Walton (1902–1983), Composer, Sitter in 22 portraits (National Portrait Gallery collection)

- "The Jazz Age", lecture and concert by Chamber Domaine given on 6 November 2007 at Gresham College, including Walton's Façade (available for audio and video download).

- Walton, Cello Concerto on YouTube performed by Julian Lloyd Webber and the Academy of St Martin in the Fields conducted by Sir Neville Marriner

- William Walton at the British Film Institute's Screenonline

- Walton, as remembered by his widow (by Paolo Petrocelli)

- "William Walton material". BBC Radio 3 archives.

- William Walton on IMDb