William Thaddeus Coleman Jr.

| Bill Coleman | |

|---|---|

| |

| Judge of the United States Court of Military Commission Review | |

|

In office September 21, 2004 – December 17, 2009 | |

| Appointed by | George W. Bush |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | Scott Silliman |

| 4th United States Secretary of Transportation | |

|

In office March 7, 1975 – January 20, 1977 | |

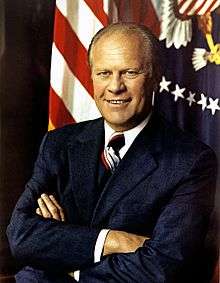

| President | Gerald Ford |

| Preceded by | Claude Brinegar |

| Succeeded by | Brock Adams |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

July 7, 1920 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Died |

March 31, 2017 (aged 96) Alexandria, Virginia, U.S. |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse(s) | Lovida Hardin |

| Children | 3 (including William, Hardin) |

| Education |

University of Pennsylvania (BA) Harvard University (LLB) |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance |

|

| Service/branch |

|

| Unit | United States Army Air Corps |

| Battles/wars | World War II |

William Thaddeus "Bill" Coleman Jr. (July 7, 1920 – March 31, 2017) was an American attorney and politician.[1][2] Coleman was the fourth United States Secretary of Transportation, from March 7, 1975, to January 20, 1977, and the second African American to serve in the United States Cabinet. As an attorney, Coleman played a major role in significant civil rights cases. At the time of his death, Coleman was the oldest living former Cabinet member.[lower-alpha 1]

Early life and education

Coleman was born to William Thaddeus Coleman Sr. and Laura Beatrice (née Mason) Coleman in Germantown, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.[1] Coleman's mother came from six generations of Episcopal ministers, including an operator of the Underground Railroad.[1] W.E.B. DuBois and Langston Hughes would visit the family’s home for dinner.[1] One of seven black students at Germantown High School, Coleman was suspended for cursing at a teacher after she praised his honors presentation by saying, "Someday, William, you will make a wonderful chauffeur."[1] When Coleman attempted to join the school's swim team he was again suspended, and the team disbanded after he returned so as to avoid admitting him, only to reform after he graduated.[1] Coleman’s swim team coach wrote him a strong letter of recommendation and he was accepted into the University of Pennsylvania, where he was a double major in political science and economics.[1]

He graduated summa cum laude from the University of Pennsylvania with a B.A. in history in 1941.[2] There, he was elected to the Phi Beta Kappa Society.[2] He was elected to the Pi Gamma Mu international honor society in 1941.[3] Coleman was also a member of Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity.[4]

Colman was accepted to the Harvard Law School but left in 1943 to enlist in the Army Air Corps, failing in his attempt to join the Tuskeegee Airmen.[1] Instead, Coleman spent the war defending the accused in court-martials.[1] After the war, Coleman returned to Harvard Law, where he became the first black staff member accepted to the Harvard Law Review, and graduated first in his class and magna cum laude in 1946.[1]

Career

He began his legal career in 1947, serving as law clerk to Judge Herbert F. Goodrich of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit and U.S. Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter in 1948. He was the first African American to serve as a Supreme Court law clerk.[5] Fellow clerks, including Elliot Richardson, would have difficulty finding a restaurant where they could eat together.[1]

Coleman was hired by the New York law firm of Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison in 1949.[6] Thurgood Marshall, then the chief counsel of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, recruited Coleman to be one of the lead strategists and coauthor of the legal brief in Brown v. Board of Education (1954), in which the U.S. Supreme Court held racial segregation in public schools to be unconstitutional.[1]

He served as a member of the NAACP's national legal committee, director and member of its executive committee, and president of board of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund. Coleman was also a member of President Dwight D. Eisenhower's Committee on Government Employment Policy (1959–1961) and a consultant to the U.S. Arms Control and Disarmament Agency (1963–1975). Coleman served as an assistant counsel to the President's Commission on the Assassination of President Kennedy (1964), also known as the Warren Commission, on which then-Congressman Gerald Ford was a commissioner.[1]

During the Warren Commission's investigation into the assassination of John F. Kennedy, the Commission received word via a backchannel that Fidel Castro, then Prime Minister of Cuba, wanted to talk to them. The Commission sent Coleman as an investigator and he met with Castro on a fishing boat off the coast of Cuba. Castro denied any involvement in the assassination of President Kennedy during Coleman's three-hour questioning. Coleman reported the results of his investigation and interview with Castro directly to Commission Chairman Earl Warren, the Chief Justice of the United States.[7]

Coleman was co-counsel to the petitioners in McLaughlin v. Florida (1964), in which the Supreme Court unanimously struck down a law prohibiting an interracial couple from living together.[1] In 1969, he was a member of the U.S. delegation to the twenty-fourth session of the United Nations General Assembly. Coleman was also a member of the National Commission on Productivity (1971–1972). Coleman served in the boardrooms of PepsiCo, IBM, Chase Manhattan Bank, and Pan American World Airways.[1] He was senior partner in the law firm of Dilworth, Paxson, Kalish, Levy & Coleman at the time of his appointment to the Ford Administration.

Cabinet post

President Gerald Ford appointed Coleman to serve in the Cabinet of the United States as the fourth United States Secretary of Transportation on March 7, 1975.[8] During Coleman's tenure at the United States Department of Transportation, the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration's automobile test facility at East Liberty, Ohio commenced operations, and the Department established the Materials Transportation Bureau to address pipeline safety and the safe shipment of hazardous materials. In May 1976, Coleman authorized a testing period for the supersonic Concorde jet.[1] After the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey banned the jet, the U.S. Supreme Court restored Coleman’s authorization.[1] In December 1976, Coleman rejected consumer activists’ pressure for a federal mandate on automobile airbags and instead announced a two-year demonstration period favored by the auto industry.[1] Coleman's tenure ended after Jimmy Carter won the United States presidential election, 1976.

Post-Cabinet service and honors

On leaving the department, Coleman returned to Philadelphia and subsequently became a partner in the Washington office of the Los Angeles-based law firm O'Melveny & Myers. Colman argued a total of 19 cases before the Supreme Court.[1] He appeared for the respondent in the argument and reargument of Garcia v. San Antonio Metropolitan Transit Authority (1985). In 1983, with the election quickly approaching, the Reagan administration stopped supporting the IRS's position against Bob Jones University that overtly discriminatory groups were ineligible for certain tax exemptions. Coleman was appointed to argue the now unsupported lower court position before the Supreme Court, and won in Bob Jones University v. United States.[9]

On September 29, 1995, Coleman was presented with the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Bill Clinton. After the July 17, 1996 crash of TWA Flight 800, he served on the President's Commission on Airline and Airport Security. Coleman received an honorary LL.D. from Bates College in 1975. Coleman was also awarded honorary degrees from, among others, Williams College in May 1975, Gettysburg College on May 22, 2011,[10] and Boston University in May 2012.

In September 2004, President George W. Bush appointed Coleman to the United States Court of Military Commission Review.[8]

In December 2006, Coleman served as an honorary pallbearer during the state funeral of Gerald Ford in Washington, D.C..[11][12]

Personal life

In 1945, he married Lovida Mae Hardin. They have three children: Lovida H. Coleman, William Thaddeus Coleman III, a General Counsel of the Army under President Clinton; stepfather of Flavia Colgan, and Hardin Coleman, dean, Boston University School of Education.

Coleman, Jr. died from complications of Alzheimer's disease at his home in Alexandria, Virginia on March 31, 2017, aged 96.[1]

See also

- List of African-American United States Cabinet Secretaries

- List of law clerks of the Supreme Court of the United States

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Hevesi, Dennis (1 April 2017). "William T. Coleman Jr., Who Broke Racial Barriers in Court and Cabinet, Dies at 96". The New York Times. p. A24. Retrieved 4 April 2017.

- 1 2 3 Schudel, Matt (March 31, 2017). "William T. Coleman Jr., transportation secretary and civil rights lawyer, dies at 96". Washington Post. Retrieved March 31, 2017.

- ↑ "Prominent Pi Gamma Mu Members-entry for William T. Coleman". Pi Gamma Mu Fraternity. Retrieved April 4, 2017.

- ↑ "Alpha Phi Alpha Politicians". The Political Graveyard. Retrieved 2009-12-11.

- ↑ Greenhouse, Linda (2006-08-30). "Supreme Court Memo; Women Suddenly Scarce Among Justices' Clerks". The New York Times.

- ↑ "Paul Weiss, Diversity".

- ↑ "Warren Commission questioned Fidel Castro, new book reveals". CBS TV. Yahoo News. October 25, 2013. Retrieved April 1, 2017.

- 1 2 "Military Commission Review Panel Takes Oath of Office". United States Department of Defense. 2004-09-22. Retrieved 2008-11-02.

William T. Coleman Jr., Ford administration secretary of transportation. Coleman's public service includes advisory or consultant positions to six presidents. Coleman was a member of the U.S. delegation to the 24th session of the United Nations General Assembly in 1969. He graduated magna cum laude from Harvard Law School in 1946.

mirror - ↑ Turner, Daniel (2002). Standing Without Apology: The History of Bob Jones University. Greenville, SC: BJU Press. p. 230. ISBN 1579247105.

On April 19, the Court announced that it would not allow the NAACP to join the case, and in a step considered unprecedented by legal scholars and 'extraordinary' even to the NAACP's leadership, the Supreme Court appointed a prosecutor of its own—black attorney and civil rights activist William T. Coleman. Bob Jones III commented that 'this puts the court in the position of creating an issue to be litigated and insisting that an issue be heard when one of the two litigants declares 'no contest'.

- ↑ "List of recipients of honorary degrees". Gettysburg College. Retrieved 2017-01-13.

- ↑ "Honorary Pallbearers at Funeral Services for President Gerald R. Ford". Gerald Ford Presidential Library. Retrieved March 31, 2017.

- ↑ Ritchie, Donald (January 2, 2007). "Transcript: The Ford Funeral". Washington Post. Retrieved March 31, 2017.

Notes

- ↑ Coleman was five months older than George P. Shultz.

External links

- Biography at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library and Museum

- Biography at AmericanPresident.org

- William Coleman's oral history video excerpts at The National Visionary Leadership Project

- ALI Reporter

- "Remarks by the President in Presentation if the Presidential Medal Of Freedom" – September 29, 1995

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Claude Brinegar |

United States Secretary of Transportation 1975–1977 |

Succeeded by Brock Adams |

| Legal offices | ||

| New seat | Judge of the United States Court of Military Commission Review 2004–2009 |

Succeeded by Scott Silliman |