William Stewart Halsted

| William Stewart Halsted | |

|---|---|

|

William Stewart Halsted in 1922 | |

| Born |

September 23, 1852 New York City |

| Died |

September 7, 1922 (aged 69) Johns Hopkins Hospital |

| Nationality | United States |

| Fields | Medicine |

| Institutions | Johns Hopkins Hospital |

| Alma mater | Yale University; College of Physicians & Surgeons of Columbia University |

| Known for |

inventing the residency training system in U.S. |

| Influences | Theodor Billroth |

William Stewart Halsted, M.D. (September 23, 1852 – September 7, 1922) was an American surgeon who emphasized strict aseptic technique during surgical procedures, was an early champion of newly discovered anesthetics, and introduced several new operations, including the radical mastectomy for breast cancer. Along with William Osler (Professor of Medicine), Howard Atwood Kelly (Professor of Gynecology) and William H. Welch (Professor of Pathology), Halsted was one of the "Big Four" founding professors at the Johns Hopkins Hospital.[1][2] His operating room at Johns Hopkins Hospital is in Ward G, and was described as a small room where medical discoveries and miracles take place.[3] According to an intern who once worked in Halsted's operating room, Halsted had unique techniques, operated on the patients with great confidence and often had perfect results which astonished the interns.[3]

Throughout his professional life, he was addicted to cocaine and later also to morphine,[4][5] which were not illegal during his time. As revealed by his Hopkins colleague Osler's diary, Halsted developed a high level of drug tolerance for morphine. He was "never able to be reduce the amount to less than three grains daily".[6] The addictions were a direct result of Halsted's use of himself as an experimental subject, in investigations on the effects of cocaine as an anesthetic agent.[7]

Early life and education

William S. Halsted was born on September 23, 1852 in New York City.[8] His mother was Mary Louisa Haines and his father William Mills Halsted, Jr. His father was a businessman with Halsted, Haines and Company. Halsted was educated at home by tutors until 1862, when he was sent to boarding school in Monson, Massachusetts. He didn't like his new school and even ran away at one point. He was later enrolled at Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts, where he graduated in 1869. Halsted entered Yale College the following year. At Yale, Halsted was captain of the football team, played baseball and rowed on the crew team. Upon graduation from Yale in 1874, Halsted entered Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons. He graduated in 1877 with a Doctor of Medicine degree. Though raised a Presbyterian, Halsted was an agnostic by adulthood.[9]

Medical career

After graduation, Halsted joined the New York Hospital as house physician, where he introduced the hospital chart which tracks the patient's temperature, pulse and respiration. It was at New York Hospital that Halsted met the pathologist William H. Welch, who would become his closest friend.

Halsted then went to Europe to study under the tutelage of several prominent surgeons and scientists, including Edoardo Bassini, Ernst von Bergmann, Theodor Billroth, Heinrich Braun, Hans Chiari, Friedrich von Esmarch, Albert von Kölliker, Jan Mikulicz-Radecki, Max Schede, Adolph Stöhr, Richard von Volkmann, Anton Wölfler, Emil Zuckerkandl.

Halsted returned to New York in 1880 and for the next six years led an extraordinarily vigorous and energetic life. He operated at multiple hospitals, including Roosevelt Hospital, the College of Physicians and Surgeons, Charity Hospital, Emigrant Hospital, Bellevue Hospital and Chambers Street Hospital. He was an extremely popular, inspiring and charismatic teacher. In 1882 he performed one of the first gallbladder operations in the United States, a cholecystotomy performed on his mother on the kitchen table at 2 am. Halsted also performed one of the first blood transfusions in the United States. He had been called to see his sister after she had given birth. He found her moribund from blood loss, and in a bold move withdrew his own blood, transfused his blood into his sister, and then operated on her to save her life.

In 1884, Halsted read a report by the Austrian ophthalmologist Karl Koller, describing the anesthetic power of cocaine when instilled on the surface of the eye. Halsted, his students, and fellow physicians experimented on each other, and demonstrated that cocaine could produce safe and effective local anesthesia when applied topically and when injected.[10] In the process, Halsted became addicted to the drug. His close friend Harvey Firestone recognized the gravity of the situation, and arranged for Halsted to be abducted and put aboard a steamer headed for Europe. In the two weeks it took to complete the voyage, Halsted underwent an early, crude form of detoxification. Upon his return to the United States he became addicted again, and was sent to Butler Sanatorium in Providence, Rhode Island, where they attempted to cure his cocaine addiction with morphine. Although he remained dependent upon morphine for the remainder of his life, he continued his career as a pioneering surgeon; many of his innovations remain standard operating room procedures.[11]

After his discharge from Butler in 1886, Halsted moved to Baltimore, Maryland to join his friend William Welch in organizing and launching the new Johns Hopkins Hospital. When it opened in May 1889, he became its first Chief of Surgery. In 1892, Halsted joined Welch, William Osler, and Howard Kelly in founding the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, and was appointed its first Professor of Surgery.[12]

Halsted was credited with starting the first formal surgical residency training program in the United States at Johns Hopkins. The program began with an internship of undefined length (individuals advanced once Halsted believed they were ready for the next level of training), followed by six years as an assistant resident, and then two years as house surgeon. Halsted trained many of the prominent academic surgeons of the time, including Harvey Williams Cushing and Walter Dandy, founders of the surgical subspecialty of neurosurgery; and Hugh H. Young, a founder of the specialty of urology.[13]

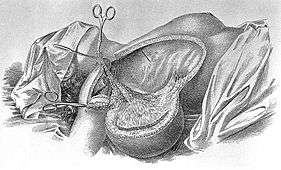

He is also known for many other medical and surgical achievements. As one of the first proponents of hemostasis and investigators of wound healing, Halsted pioneered Halsted's principles, modern surgical principles of control of bleeding, accurate anatomical dissection, complete sterility, exact approximation of tissue in wound closures without excessive tightness, and gentle handling of tissues. In 1882 Halsted performed the first radical mastectomy for breast cancer in the U.S. at Roosevelt Hospital in New York;[14][15] an operation first performed in France a century earlier by Bernard Peyrilhe (1735-1804).[16] Other achievements included the introduction of the latex surgical glove and advances in thyroid, biliary tract, hernia,[17] intestinal and arterial aneurysm surgery.

H.L. Mencken considered Halsted the greatest physician of the whole Johns Hopkins group, and Mencken’s praise of his achievements when he reviewed Dr. MacCallum's 1930 biography is a memorable tribute. “His contributions to surgery were numerous and various. He introduced the use of local anesthetics, he was the first to put on rubber gloves, and he devised many new and ingenious operations. But his chief service was rather more general, and hard to describe. It was to bring in a new and better way of regarding the patient. Antisepsis and asepsis, coming in when he was young, had turned the attention of surgeons to external and often extraneous things. Fighting germs, they tended to forget the concrete sick man on the table. Dr. Halsted changed all that. He showed that manhandled tissues, though they could not yell, could yet suffer and die. He studied the natural recuperative powers of the body, and showed how they could be made to help the patient. He stood against reckless slashing, and taught that a surgeon must walk very warily. Dr. William Mayo, one of the cofounders of the Mayo Clinic, once commented that Dr. Halsted took so long to perform procedures that the patients usually healed before he had a chance to close the incision.[18] Though, like most men of his craft, he had no religion, he yet revived and reinforced the ancient saying of Ambroise Paré: ‘God cured him; I assisted.’ Above all, he was a superb teacher, though he never formally taught. The young men who went out from his operating room were magnificently trained, and are among the great ornaments of American surgery today.”[19]

In 1890, Halsted married Caroline Hampton, the niece of Wade Hampton III, a former general in the Confederate States Army and also a former Governor of South Carolina. They purchased the High Hampton mountain retreat in North Carolina from Caroline's three aunts. There, Halsted raised dahlias and pursued his hobby of astronomy; he and his wife had no children.[20] He died on September 7, 1922, 16 days short of his 70th birthday, from bronchopneumonia as a complication of surgery for gallstones and cholangitis.[8][21]

Eponyms

- Halsted's law: transplanted tissue will grow only if there is a lack of that tissue in the host

- Halsted's operation I: operation for inguinal hernia[17]

- Halsted's operation II: radical mastectomy for breast cancer

- Halsted's sign: a medical sign for breast cancer

- Halsted's suture: a mattress suture for wounds that produced less scarring

- Halsted mosquito forceps: a type of hemostat

See also

References

- ↑ Roberts, CS (2010). "H.L. Mencken and the four doctors: Osler, Halsted, Welch and Kelly". Baylor University Medical Center Proceedings. 23 (4): 377–88. PMC 2943453

. PMID 20944761.

. PMID 20944761. - ↑ Johns Hopkins Medicine:The Four Founding Professors

- 1 2 Markel, Howard (2012). An Anatomy of Addiction: Sigmund Freud, William Halsted, and the Miracle Drug, Cocaine. New York: Pantheon Books. p. 188. ISBN 978-1400078790.

- ↑ Zuger, A (April 26, 2010). "Traveling a Primeval Medical Landscape". The New York Times.

- ↑ Brecher, Edward M.; and the Editors of Consumer Reports (1972). "Licit and Illicit Drugs, Chapter 5, 'Some eminent narcotics addicts'". Schaffer Library of Drug Policy. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- ↑ Markel, Howard (2011). An Anatomy of Addiction. Sigmund Freud, William Halsted, and the Miracle Drug Cocaine. Pantheon Books. p. 211.

- ↑ Imber G: Genius on the Edge: The Bizarre Double Life of Dr. William Stewart Halsted. New York: Kaplan Publishing. ISBN 978-1-60714-627-8. OCLC 430842094

- 1 2 "Dr. Wm. S. Halsted Dies At Johns Hopkins. Professor of Surgery There for 33 Years Was One of the Foremost Leaders in Medical Science.". New York Times. September 8, 1922. Retrieved 2010-03-03.

Dr. William Stuart Halsted, professor of surgery at Johns Hopkins Medical School for many years as one of the foremost leaders in ... died today....

- ↑ "William Stewart Halsted". Annals of Surgery. Retrieved 2010-03-03.

- ↑ Halsted, William S. (1885). "Practical comments on the use and abuse of cocaine". The New York Medical Journal. 42: 294–95.

- ↑ Imber, G. Genius on the Edge: The Bizarre Double Life of Dr. William Stewart Halsted. Kaplan Publishing (2010), pp. 138-43.

- ↑ Imber (2011), pp. 162-4.

- ↑ Imber (2011), pp. 183-5.

- ↑ The Breast: Comprehensive Management of Benign and Malignant Diseases, Volume 2 by Kirby I. Bland and Edward M. Copeland III, 4th ed., 2009, pg. 721

- ↑ Mukherjee, Siddhartha (November 16, 2010). The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of Cancer. Simon and Schuster. p. 23. ISBN 978-1-4391-0795-9. Retrieved September 6, 2011.

- ↑ B. Peyrhile, "Dissertatio academica de cancro," The Lyon Academy, (1773)

- 1 2 Halsted, WS (1893). "The radical cure of inguinal hernia in the male" (PDF). Annals of Surgery. 17 (5): 542–56. PMC 1492972

. PMID 17859917.

. PMID 17859917. - ↑ Markel, Howard (July 19, 2011). An Anatomy of Addiction: Sigmond Freud, William Halstead, and the Miracle Drug, Cocaine. New York: Vintage Books. p. 189. ISBN 978-1400078790.

- ↑ H.L. Mencken, "A Great American Surgeon," American Mercury, v. 22, no. 87 (March 1931) 383. Review of William Stewart Halsted, Surgeon, by W.G. MacCallum. Mencken on Halsted.

- ↑ High Hampton history

- ↑ Imber G: Ref. 5, op cit.

Further reading

- Brecher, Edward M.; and the Editors of Consumer Reports (1972). Licit and Illicit Drugs, Chapter 5, 'Some eminent narcotics addicts'. Schaffer Library of Drug Policy. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- Cameron, John. (1997). "Williams Stewart Halsted: Our Surgical Heritage". Annals of Surgery. 225 (5): 445–58. PMC 1190776

. PMID 9193173. doi:10.1097/00000658-199705000-00002.

. PMID 9193173. doi:10.1097/00000658-199705000-00002. - Garrison, Fielding H. "Halsted," American Mercury, v. 7, no. 28 (April 1926) 396–401.

- Sherman, I; Kretzer, Ryan M.; Tamargo, Rafael J. (September 2006). "Personal recollections of Walter E. Dandy and his Brain Team". Journal of Neurosurgery. 105 (3): 487–93. PMID 16961151. doi:10.3171/jns.2006.105.3.487.

- Nuland, Sherwin B. (1988). Doctors: the Biography of Medicine. New York: Knopf. ISBN 0-394-55130-3.

- "Who named it?". William Stewart Halsted. Retrieved August 3, 2005.

- "A Tribute to William Stewart Halsted, MD". William Stewart Halsted. Retrieved August 18, 2005.

- Bryan, Charles S. (1999). "Caring Carefully: Sir William Osler on the issue of competence vs. compassion in medicine". Baylor University Medical Center Proceedings. 12 (4): 277–84.

- Halsted, William S. (1885). "Practical comments on the use and abuse of cocaine". The New York Medical Journal. 42: 294–95.

- Halsted, William S. (1887). "Practical Circular suture of the intestines; an experimental study". The American Journal of the Medical Sciences. 94: 436–61. doi:10.1097/00000441-188710000-00010.

- Halsted, William S. (1890–1891). "The treatment of wounds with especial reference to the value of the blood clot in the management of dead spaces". The Johns Hopkins Hospital Reports. 2: 255–314. First mention of rubber gloves in the operating room.

- Halsted, William S. (1892). "Ligation of the first portion of the left subclavian artery and excision of a subclavio-axillary aneurism". The Johns Hopkins Hospital Bulletin. 3: 93–4.

- Halsted, William S. (1894–1895). "The results of operations for the cure of cancer of the breast performed at the Johns Hopkins Hospital from June, 1899, to January, 1894". The Johns Hopkins Hospital Reports. 4: 297.

- Halsted, William S. (1899). "The Contribution to the surgery of the bile passages, especially of the common bile-duct". The Boston Medical and Surgical Journal. 141 (26): 645–54. doi:10.1056/nejm189912281412601.

- Halsted, William S. (1925). "Auto- and isotransplantation, in dogs, of the parathyroid glandules". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 63: 395–438.

- Halsted WStitle=Partial progressive and complete occlusion of the aorta and other large arteries in the dog by means of the metal band (March 1, 1909). "PARTIAL, PROGRESSIVE AND COMPLETE OCCLUSION OF THE AORTA AND OTHER LARGE ARTERIES IN THE DOG BY MEANS OF THE METAL BAND". The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 11 (2): 373–91. PMC 2124707

. PMID 19867254. doi:10.1084/jem.11.2.373.

. PMID 19867254. doi:10.1084/jem.11.2.373. - Halsted WS (1915). "A diagnostic sign of gelatinous carcinoma of the breast". Journal of the American Medical Association. 64 (20): 1653. doi:10.1001/jama.1915.02570460029011.

- Burjet, W.C., Ed. (1924). Surgical Papers by William Stewart Halsted. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press.

- MacCallum WG (1930). William Stewart Halsted, surgeon. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press.

- Imber, G (2010). Genius on the Edge: The Bizarre Double Life of Dr. William Stewart Halsted. New York: Kaplan Publishing. ISBN 978-1-60714-627-8. OCLC 430842094.

External links

- "Re-Examining The Father Of Modern Surgery". Fresh Air. February 22, 2010. An interview with Gerald Imber, author of Genius on the Edge, and an excerpt from the book.

- A documentary on the life of Dr. Halsted recently aired on the public broadcasting station WETA "Halsted The Documentary".

- National Academy of Sciences Biographical Memoir