William Henry Reed

William Henry "Billy" Reed (29 July 1875 – 2 July 1942) was an English violinist, teacher, minor composer, conductor and biographer of Sir Edward Elgar. He was leader of the London Symphony Orchestra for 23 years (1912–1935), but is best known for his long personal friendship with Elgar (1910–1934) and his book Elgar As I Knew Him (1936), in which he goes into great detail about the genesis of the Violin Concerto in B minor. The book also provides a large number of Elgar's sketches for his unfinished Third Symphony, which proved invaluable sixty years later when Anthony Payne elaborated and essentially completed the work, although Reed wrote that in his view the symphony could not be completed.

His name appears in various forms: William Henry Reed, W. H. Reed, W. H. "Billy" Reed, Billy Reed and Willie Reed. He was known to his friends as Billy.

Biography

William Henry Reed was born in Frome, Somerset. He studied at the Royal Academy of Music in London under Émile Sauret,[1] Frederick Corder and others,[2] graduating with honours.[3]

He first met Edward Elgar in 1902, as a violinist in the Queen's Hall Orchestra. On 17 January, Elgar has just completed a rehearsal of his incidental music to Grania and Diarmid with the orchestra, when Reed approached him, introduced himself, and asked whether he gave lessons in harmony and counterpoint. Elgar said "My dear boy, I don't know anything about those things".[4] They did not become personal friends at that time; however, their paths continued to cross in the course of their work. Reed was a founding member of the London Symphony Orchestra in 1904.[1] His physical appearance was quite similar to that of Elgar's close friend August Jaeger (the "Nimrod" of the Enigma Variations of 1899), and that may have played some part in Elgar's always having something positive and encouraging to say to Reed whenever they happened to meet.[3]

On 27 May 1910,[5] Elgar and Reed happened by chance to meet in Regent Street, London. Elgar said he was having some problems with the writing of his Violin Concerto and asked Reed if he could assist him. This was the real beginning of their great friendship, which lasted until Elgar's death in February 1934. Reed was the first to play through the sketches of the concerto, at Elgar's flat. He was also the first to play the concerto before an audience, in a semi-public performance at the Three Choirs Festival in Gloucester on 4 September 1910.[5][6] The official premiere of the work was on 10 November, with the dedicatee Fritz Kreisler as soloist.

Elgar was Principal Conductor of the London Symphony Orchestra in 1911-1912, and Reed became the leader of the orchestra in 1912.[1] In 1914 Elgar dedicated his piece for strings and organ, Sospiri, Op. 70 to Billy Reed.[7][8] Reed had himself been composing for some years by now: his String Quartet No. 5 in A minor won a second prize in the Cobbett Competition in 1916.[9]

Elgar continued to turn to Reed for advice on technical problems involving the violin, such as the Violin Sonata in E minor, Op. 82 (1918). The sonata was premiered in 1919 at the Aeolian Hall, London, by Billy Reed, with Landon Ronald at the piano.[10] Reed also gave the second performance, but the work's main players then became Albert Sammons and William Murdoch. Reed also participated in the first performances of the String Quartet in E minor, Op. 83 and the Piano Quintet in A minor, Op. 84.[1][11] These three works were written concurrently, when Elgar was living at Brinkwells, near Fittleworth in Sussex, and Reed often stayed at his house and went walking with him during this time.[12]

Elgar's wife died in 1920, and at her funeral at St Wulstan's Church, Little Malvern, Billy Reed was part of the quartet that played a movement from Elgar's String Quartet.[13]

In 1932 Elgar started writing his Third Symphony in earnest, after a BBC commission in which Reed and George Bernard Shaw played a part. He had been musing over such a work for some years, and had jotted down various themes and ideas on different pieces of manuscript paper. Now, he set about bringing them all together. He and Billy Reed would often try out certain sketches on violin and piano. In October 1933, however, Elgar's cancer was diagnosed, and he died in February 1934. During that period of illness, he was able to jot down only a few more notes for the symphony, and he knew he would not be able to finish it. In December 1933, he said to Reed: "Don't let them tinker with it, Billy - burn it!"[14] But Reed kept the sketches, amounting to 172 pages.[15] After Elgar's death, George Bernard Shaw encouraged Reed to record his memories of Elgar; the book Elgar As I Knew Him was published in 1936, two years after Elgar's death.[7] The book included facsimile reproductions of many of the 172 pages of sketches and also the instructions Elgar had given Reed for playing them and his guidance on where each sketch fitted into the overall work.[14] Reed had also published the complete sketches in his article, "Elgar's Third Symphony" in The Listener (23 August 1935).[15] These and other materials were later to prove invaluable for Anthony Payne, who first came across them in Reed's book in 1972. The first recording of Payne's elaboration of Elgar's sketches for the Third Symphony included a 70-minute discussion by Payne, including the sketches Elgar and Reed had played over on violin and piano. Billy Reed's own violin was used for this recording, with Robert Gibbs playing the violin and David Owen Norris the piano.[16]

W. H. Reed had ceased to be the leader of the London Symphony Orchestra in 1935, although he still assumed that role on certain special occasions.[1] Sir Thomas Beecham replaced him with Paul Beard (he was not informed personally of this dismissal, but read about it in a newspaper; indeed, Beecham had not long before assured Reed that the LSO would be unthinkable without him).[17] Instead, he became chairman of the orchestra's board of directors. He had also taught at the Royal College of Music throughout his performing career, and was made a Fellow of the college.[1] His students there included George Weldon,[18] Imogen Holst, and Jean Johnstone (the future wife of William Lloyd Webber and mother of Andrew and Julian Lloyd Webber).[19]

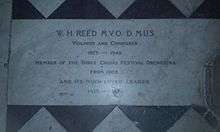

In 1939 he was awarded a Doctorate of Music by the University of Cambridge.[1] That year he wrote more on Edward Elgar as part of the "Master Musicians" series.[2]

After retirement from active performing, he devoted much of his time to examining students and adjudicating competitions. He did a great deal of work conducting amateur orchestras and ensembles. In 1933 he became conductor of the Strolling Players.[2]

It was on a trip to Scotland to examine and adjudicate for the Associated Board of the Royal Schools of Music[9] that he died suddenly, in Dumfries, on 2 July 1942, aged 65. His ashes were interred in Worcester Cathedral, near the "Gerontius" window.[13][18]

In the film Elgar's Tenth Muse: The Life of an English Composer, Billy Reed was played by Rupert Frazer.[20]

Composer

W. H. Reed was also a composer in his own right and established a growing reputation. Some of his works were given their first performances at the Proms, the Three Choirs Festivals, and at Bournemouth,[2][9] but his name as a composer was overshadowed by that of an Elgar biographer, and his works slipped from the repertoire. They are now starting to be performed again and recorded.[13][21]

His works include:

|

|

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians, 5th ed, 1954

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Answers.com

- 1 2 Classy Classical

- ↑ Jerrold Northrop Moore, Edward Elgar: A Creative Life

- 1 2 Michael Steinberg, The Concerto

- ↑ Sydney Symphony Program Notes

- 1 2 Elgar – His Music: Sospiri, Op.70

- ↑ "Elgar's English Twilight, an Idyll". Archived from the original on 2012-06-30.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 Music Web International

- ↑ ArkivMusik

- ↑ Classics Online

- ↑ CMNW Program Notes

- 1 2 3 Worcester News

- 1 2 Elgar – His Music: Symphony No. 3, Op. 88

- 1 2 Classics Online

- ↑ Records International.com

- ↑ Charles Reid, Thomas Beecham: An Independent Biography, 1961, pp. 200, 203

- 1 2 George Weldon.co.uk

- ↑ A Voyage around my father

- ↑ Blockbuster

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Presto Classical

- ↑ Music Web International

- ↑ The Lied and Art Song Texts Page