William G. Enloe

| William G. Enloe | |

|---|---|

| |

| Mayor of Raleigh, North Carolina | |

|

In office 1957–1963 | |

| Preceded by | Fred B. Wheeler |

| Succeeded by | James W. Reid |

| Raleigh City Councilman | |

|

In office 1971–1972 | |

| Preceded by | Thomas W. Bradshaw |

| Succeeded by | Edith Reid |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

15 June 1902 Rock Hill, South Carolina[1] |

| Died |

November 22, 1972 (aged 70) Rex Hospital, Raleigh, North Carolina |

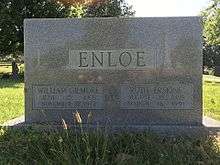

| Resting place | Historic Oakwood Cemetery |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse(s) | Ruth Erskine |

| Children | 2 |

| Residence | Raleigh, North Carolina |

William Gilmore "Bill" Enloe (15 June 1902 – 22 November 1972)[2] was the Mayor of Raleigh, North Carolina from 1957–1963.[3] Enloe was a member of the Democratic Party. William G. Enloe High School, the first integrated public high school in Raleigh, was named after him. He was mayor when the school opened in 1962.[4][5]

Biography

William Gilmore Enloe was born in South Carolina. He started his business career selling popcorn in Greenville. He eventually became the eastern district manager for North Carolina Theatres, Inc./Wilby-Kincey Theaters.[6]

Enloe came mayor of Raleigh, North Carolina in 1957.[3] In 1960 he criticized black students who participated in the Greensboro sit-ins, calling it "regrettable that some of our young Negro students would risk endangering [black and white] relations by seeking to change a long-standing custom in a manner that is all but destined to fail.”[7] In the summer of 1963 the American south was subject to a wave of violence, protests, and mass arrests. Enloe, wanting to "avoid another Birmingham," appointed a biracial "Committee of One Hundred" to resolve Raleigh's civil rights issues.[8]

Enloe was still affiliated with Wilby-Kincey Theaters during his term as mayor.[9] Among the targets of some anti-segregation demonstrators were movie theaters owned by the chain, which were designed to accommodate Jim Crow era segregation, with separate seating arrangements. Enloe resisted integration efforts. Eventually, in a meeting with United States Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, he agreed to begin desegregating them, starting with those in Greensboro, then Winston-Salem, Charlotte, Durham, and finally Raleigh.[10] At the time he was considered moderate on the issue of race relations.[9]

Enloe briefly served as a Raleigh city councilman from 1971 until his death.[11]

Enloe suffered a heart attack on November 2, 1972 while attending a North Carolina League of Municipalities convention. He died 20 days later at Rex Hospital in Raleigh.[6] He is buried next to his wife, Ruth Erskine Enloe, in Raleigh's Historic Oakwood Cemetery.[12] They had a son, William G. Enloe Jr., and a daughter, Ruth Enloe.[13]

See also

References

- ↑ "Enloe, William Gilmore (1902) › Page 2 - Fold3.com". fold3.com. Retrieved 9 September 2015.

- ↑ Historic Oakwood Cemetery

- 1 2 "raleighnc.gov". raleigh-nc.org. Retrieved 9 September 2015.

- ↑ "William G Enloe High School". publicschoolreview.com. 5 November 2014. Retrieved 9 September 2015.

- ↑ Enloe's name caught up in diversity debate

- 1 2 "W. G. Enloe dies: Veteran of 55 Years". Motion Picture Daily. Vol. 110 no. 78–102. Quigley Publishing Company. 1972. p. 84.

- ↑ Hunter-Gault, Charlayne (2012). To the Mountaintop: My Journey Through the Civil Rights Movement (illustrated ed.). Macmillan. p. 153. ISBN 9781596436053.

- ↑ Grant, Gerald (2009). Hope and Despair in the American City. Harvard University Press. p. 87. ISBN 9780674053922.

- 1 2 "Community Services". Wake County Public School System. Retrieved May 1, 2017.

- ↑ Covington, Howard E.; Ellis, Marion A. (1999), Terry Sanford: Politics, Progress, and Outrageous Ambitions (illustrated ed.), Duke University Press, p. 315, ISBN 9780822323563

- ↑ Sharpe, John (20 August 2014). Growing Up With Raleigh: Smedes York Memoirs and Reflections of a Native Son, Conversations With John Sharpe. Lulu Press Inc. ISBN 9781483410760.

- ↑ http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=83480475

- ↑ "In Memory of Ruth Enloe Hay". Brown-Wynne Funeral Home. Retrieved 15 May 2017.