William Brattle

William Brattle (April 18, 1706–October 25, 1776) was a physician, lawyer, soldier, and politician of colonial Massachusetts. During the American Revolution, he was Major General of the Royal Militia and played a role in the Powder Alarm. He was known as "the wealthiest man" in Massachusetts.[3][4][5]

Early life

William Brattle was born on April 18, 1706 in Cambridge, Massachusetts.[3] He was the son of Reverend William Brattle[6] of the First Parish in Cambridge,[7] a member of Royal Society,[6] and a Harvard graduate (1680), educator, and leader.[7][8] Brattle's father was also a slave owner.[7][lower-alpha 2] His mother was Elizabeth Hayman Brattle; she died July 28, 1715. He had an older brother, Thomas, who died as a young child.[10] He was the nephew of Thomas Brattle[11][12] and the last only descendant in the male line of Captain Thomas Brattle, his grandfather.[10]

His father died in 1717, and without a means of support, Brattle began attending Harvard, during which time he was both fined for violating college rules and was head of the class.[13] In 1722, he graduated from Harvard.[3] His classmates included Richard Saltonstall of the Saltonstall family and William Ellery.[14] He continued his studies for a graduate degree, and was head of the masters class of 1725.[13]

When he was 21 years of age,[13] Brattle inherited the estates of his father and uncle Thomas.[2] Author James Henry Stark said “He inherited a large and well invested property, and had ample means to cultivate those tastes to which, by his nature and education, he was inclined."[5]

Career

Overview

He was a physician[3] theologian, and an attorney.[5][14] Brattle was also a legislator and soldier.[14] He preached sermons in the early 1720s, but by 1725 decided that he did not want to continue to pursue the ministry and began to practice medicine, providing treatment over his years in Cambridge to residents and students.[13] He had a private law practice[15] and for many years was an overseer of Harvard.[2] Lorenzo Sabine said of him, "A man of more eminent talents, and of greater eccentricities, has seldom lived."[16]

Political career

Beginning about 1729, he served 21 terms as selectman of Cambridge.[17] He became a member of the House of Assembly of Massachusetts Bay in 1736. He then was the attorney general of the Province of Massachusetts Bay.[3]

Military career

In 1729,[2] he became a member of the Ancient and Honorable Artillery Company of Massachusetts.[5] He was a captain[14] or the major of the First Regiment of Militia in the County of Middlesex in 1733 when he wrote Sudnry rules and directions for drawing up a regiment, posting the officers.[18] He fought in the French and Indian War (1754–63).[11]

Friendly with the Sons of Liberty,[2] in 1769 he supported the revolutionary cause, but two years later he became major-general of the Militia of Great Britain in Massachusetts,[6][lower-alpha 3] He was called a "fence straddler" for "simultaneously appeasing patriots while supporting the British."[11] A Loyalist, he had notified the Royal government when people began to prepare for the Revolutionary War by storing arms.[19] In 1772, he had a significant public dispute with John Adams.[20]

Brattle wrote a letter in the autumn of 1774 to the Royal Governor of Massachusetts Bay, Thomas Gage, stating that members of the local militia were building up arms and that he feared that they were going to steal the store of gunpowder from the Charlestown Powder house. The letter was lost on its way to Gage and was found and published in a Boston newspaper. Gage had the powder barrels removed from Charlestown by 300 troops, which was seen as a means of provocation and resulted in the gathering of 4,000 people at the Cambridge Common. This incident, called the Powder Alarm, made the Tories who lived in Cambridge to feel uneasy.[11][6] Brattle moved to Boston[4] and remained on Castle Island through the siege of Boston.[21]

In the meantime, his house and other abandoned properties of the Tories were occupied by patriots. His house became the headquarters of Thomas Mifflin, the Commissary General. Regular visitors included George Washington, John Adams and Abigail Adams.[11]

Brattle left Boston in April 1776, when the British evacuated the city,[3] after securing the Governor's gun powder.

Personal life

Married at the age of 21,[15] his first wife was Katherine, the daughter of the Governor of Connecticut Gurdon Saltonstall. After she died in 1752 in Cambridge, he married Martha Fitch, the daughter of Thomas Fitch and widow of James Allen.[5] His children included Thomas and Katherine, who in 1752 was married to Boston merchant John Mico Wendall. They were the only two of nine children who survived to adulthood.[5] The William Brattle House was built for him in 1727[4][11] on Brattle Street, which is named for him.[19]

When Boston was evacuated, he moved to Halifax, Nova Scotia with General Howe in April 1776,[3] and died there on October 25, 1776 of that year.[3][22] He was buried from St. Paul's Church[3] in an unmarked grave in the Old Burying Ground.[23]

His children were allowed to keep his property in Cambridge, but his Boston and Oakham property was confiscated by the province of Massachusetts. Brattle also owned property in Halifax and southeastern Vermont.[15]

Legacy

- Brattle Street (Cambridge, Massachusetts), Brattle Square,[15] and Brattleboro, Vermont were named for him.[9][15]

Notes

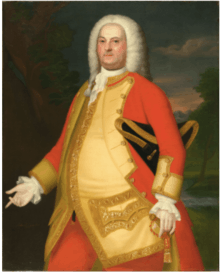

- ↑ In the painting of Brattle, Copley attempts to "illustrate the sitter's social status, provide a good likeness, and master the conventions of English painting as he understood them."[2]

- ↑ Cicely, Rev. Brattle's slave, was buried in the Old Burying Ground of Cambridge. The slate headstone reads "Here lyes the body of Cicely, Negro, late Servant to the Reverend Minister William Brattle; she died April 8. 1714. Being 15 years old."[9]

- ↑ The Bennington Banner states that he became Brigadier in 1760 and a Major General in 1773.[15]

References

- ↑ "William Brattle (1706-1776)". Harvard Art Museums, Harvard University. Retrieved May 17, 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Harvard Art Museums; Theodore E. Stebbins; Melissa Renn (January 11, 2014). American Paintings at Harvard: Volume 1: Paintings, Watercolors, and Pastels by Artists Born Before 1826. Yale University Press. p. 77. ISBN 978-0-300-15352-1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Allan E. Marble (March 1, 1997). Surgeons, Smallpox and the Poor: A History of Medicine and Social Conditions in Nova Scotia, 1749-1799. McGill-Queen's Press. pp. 36, 278. ISBN 978-0-7735-1639-7.

- 1 2 3 "William Brattle House". Cambridge Historical Tours. Retrieved May 17, 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 James Henry Stark (1907). The Loyalists of Massachusetts and the Other Side of the American Revolution. J.H. Stark. pp. 294–297.

- 1 2 3 4 Frank R. Safford (October 13, 1955). "Tory Row: Circling the Square". The Harvard Crimson. Harvard University. Retrieved May 17, 2017.

- 1 2 3 Aaron J. Miller (November 12, 2015). "Royall Must Live: Harvard’s dark past can't vanish". The Harvard Crimson. Harvard University. Retrieved May 17, 2017.

- ↑ John Langdon Sibley (1885). Biographical Sketches of Graduates of Harvard University: In Cambridge, Massachusetts. C. W. Sever. pp. 200–207.

- 1 2 Jeff Neal (October 28, 2015). "Amid the Old Burying Ground". Harvard Gazette. Retrieved May 17, 2017.

- 1 2 John Langdon Sibley (1885). Biographical Sketches of Graduates of Harvard University: In Cambridge, Massachusetts. C. W. Sever. p. 206.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "William Brattle House". Cambridge Historical Society. Retrieved May 17, 2017.

- ↑ John Langdon Sibley (1885). Biographical Sketches of Graduates of Harvard University: In Cambridge, Massachusetts. C. W. Sever. p. 202.

- 1 2 3 4 Clifford Shipton. "William Brattle". Sibley's Harvard Graduates. 7. pp. 10–11.

- 1 2 3 4 Duane Hamilton Hurd (1890). History of Middlesex County, Massachusetts: With Biographical Sketches of Many of Its Pioneers and Prominent Men. J. W. Lewis & Company. p. 38.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Williams Brattle's Borough Revives 'Uncle Bill's' Memory". Bennington Banner. Bennington, Vermont. June 25, 1966. p. 21. Retrieved May 16, 2017 – via newspapers.com. (Subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Lorenzo Sabine (1847). The American Loyalists. Boston: Charles C. Little and James Brown. p. 174.

- ↑ Clifford Shipton. "William Brattle". Sibley's Harvard Graduates. 7. p. 12.

- ↑ William Brattle (1733). Sudnry rules and directions for drawing up a regiment, posting the officers, &c. Taken from the best and latest authority; for the use and benefit of the First Regiment of Militia in the County of Middlesex. Boston – via University of Oxford Text Archive.

- 1 2 Zachary M. Seward (April 16, 2008). "Get Me Rewrite! Halberstam Street might confuse tourists, but it would honor history". The Harvard Crimson. Harvard University. Retrieved May 17, 2017.

- ↑ Clifford Shipton. "William Brattle". Sibley's Harvard Graduates. 7. pp. 18–19.

- ↑ Robert Richmond (1971). Powder Alarm, 1774. Great Events in World History. Auerbach. p. 7. ISBN 0-87769-073-1.

- ↑ Clifford Shipton. "William Brattle". Sibley's Harvard Graduates. 7. p. 23.

- ↑ Stephen Davidson (January 22, 2017). "Massachusetts Loyalists Buried in Halifax". Loyalist Trails, UELAC Newsletter. Retrieved May 17, 2017.

Further reading

- William Brattle. "William Brattle's testimony against Nathan Prince, Nov. 27, 1741". Colonial North American Project. Harvard Library, Harvard University.

- William Brattle (January 18, 1773). "William Brattle to the Boston Gazette". Founders Online, The National Historical Publications and Records Commission (NHPRC), National Archives.

- William Pencak (2004), Brattle, William (1706–1776), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/68472