Wilbur-Ellis Co. v. Kuther

| Wilbur-Ellis Co. v. Kuther | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Argued February 20, 1964 Decided June 8, 1964 | |

| Full case name | Wilbur-Ellis Co., et al. v. Kuther |

| Citations |

84 S. Ct. 1561; 12 L. Ed. 2d 419; 1964 U.S. LEXIS 2351; 141 U.S.P.Q. (BNA) 703 |

| Prior history | Cert. to the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit |

| Holding | |

| Modifying the machine to improve its functionality was akin to permissible repair, which Aro had held lawful. | |

| Court membership | |

| |

| Case opinions | |

| Majority | Douglas, joined by Warren, Black, Clark, Brennan, Stewart, White, Goldberg |

| Dissent | Harlan |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

Wilbur-Ellis Co. v. Kuther, 377 U.S. 422 (1964), is a United States Supreme Court decision that extended the repair-reconstruction doctrine of Aro Mfg. Co. v. Convertible Top Replacement Co.[1] to enhancement of function.

Background

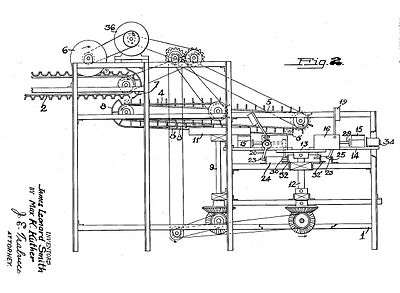

Wilbur-Ellis Company (Wilbur-Ellis) purchased four used, patented sardine-canning machines that were badly in need of repair.[2] Wilbur-Ellis tried to persuade Kuther, the patent owner, who had originally made and sold the machines, to refurbish them but met with no success. Wilbur-Ellis therefore hired a mechanic to repair and modify them so that they would handle different sized cans and different sized sardines.[3] Kuther then sued Wilbur-Ellis for “making” the machine anew.

Opinion of the Court

The Supreme Court (per Justice Douglas) held that modifying the machine to improve its functionality was akin to permissible repair, which Aro had held lawful. The patent did not cover the size of the cans or of the sardines, and Wilbur-Ellis did not replace all of the parts of the machine. No replaced part was patented individually. The patented machine was a combination of unpatented parts.[4] Although the machines were in poor condition, they were not worn out or "spent"--"they had years of usefulness remaining though they needed cleaning and repair."[5]

Kuther "in adapting the old machines to a related use [did] more than repair in the customary sense" but it "was kin to repair for it bore on the useful capacity of the old combination, on which the royalty had been paid."[6] Kuther's original sale of the machines exhausted the patent monopoly.[7] The Court thus held that modification of the patented machine to enhance its functionality was part of the property right of the machine's owner, just as the right to repair it to keep it in good order was.

Justice John Marshall Harlan II dissented on the basis of the opinion of the lower court.

References

| The citations in this Article are written in Bluebook style. Please see the Talk page for this Article. |

- ↑ 365 U.S. 336 (1961).

- ↑ They were "corroded, rusted, and inoperative; and all required cleaning and sandblasting to make them usable." 377 U.S. at 423.

- ↑ Wilbur-Ellis replaced six of the 35 parts with different sized components, so that the machine would pack 5-ounce cans instead of 1-pound cans. 377 U.S. at 423.

- ↑ 377 U.S. at 423.

- ↑ 377 U.S. at 424.

- ↑ 377 U.S. at 425.

- ↑ 377 U.S. at 425 (citing Adams v. Burke and United States v. Univis Lens Co.).