Wicklow

| Wicklow Cill Mhantáin | ||

|---|---|---|

| Town | ||

|

Farmland and view of Wicklow Town | ||

| ||

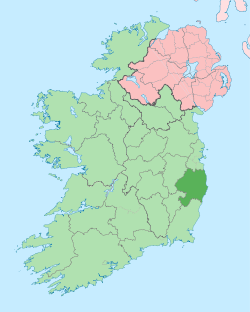

Wicklow Location in Ireland | ||

| Coordinates: 52°58′40″N 6°01′59″W / 52.9779°N 6.033°WCoordinates: 52°58′40″N 6°01′59″W / 52.9779°N 6.033°W | ||

| Country | Ireland | |

| Province | Leinster | |

| County | County Wicklow | |

| Elevation | 69 m (226 ft) | |

| Population (2011) | ||

| • Urban | 6,761 | |

| • Rural | 3,595 | |

| Irish Grid Reference | T312940 | |

| Website |

www | |

Wicklow (Irish: Cill Mhantáin, meaning "church of the toothless one")[1][2] is the county town of County Wicklow and the capital of the Mid-East Region in Ireland. Located south of Dublin on the east coast of the island, it has a population of 10,356 according to the 2011 census.[3] The town is to the east of the N11 route between Dublin and Wexford. Wicklow is also linked to the rail network, with Dublin commuter services now extending to the town. Additional services connect with Arklow, Wexford and Rosslare Europort, a main ferry port. There is also a commercial port, mainly importing timber and textiles. The River Vartry is the main river which flows through the town.

Geography

.jpg)

Wicklow town forms a rough semicircle around Wicklow harbour. To the immediate north lies 'The Murrough', a popular grassy walking area beside the sea, and the eastern coastal strip. The Murrough is a place of growing commercial use, so much so that a road by-passing the town directly to the commercial part of the area commenced construction in 2008 and was completed in summer of 2010. The eastern coastal strip includes Wicklow bay, a crescent shaped stone beach approximately 10 km in length.

Ballyguile Hill is to the southwest of the town. Much of the housing developments of the 1970s and 1980s occurred in this area, despite the considerable gradient from the town centre.

The land rises into rolling hills to the west, going on to meet the Wicklow Mountains in the centre of the county. The dominant feature to the south is the rocky headlands of Bride's Head and Wicklow Head, the easternmost mainland point of the Republic of Ireland. On a very clear day it is possible to see the Snowdonia mountain range in Wales.

Climate

Similar to much of the rest of northwestern Europe, Wicklow experiences a maritime climate (Cfb) with cool summers, mild winters, and a lack of temperature extremes. The average maximum January temperature is 9.2 °C (48.6 °F), while the average maximum August temperature is 21.2 °C (70.2 °F). On average, the sunniest month is May. The wettest month is October with 118.9 mm (4.6 in) of rain and the driest month is April with 60.7 mm (2.4 in). With the exceptions of October and November, rainfall is evenly distributed throughout the year with rainfall falling within a relatively narrow band of between 60 (2.4 in) and 86 mm (3.4 in) for any one month. However, a considerable spike occurs in October and November each of which records almost double the typical rainfall of April.

Wicklow is sheltered locally by Ballyguile hill and, more distantly by the Wicklow mountains. This sheltered location makes it one of the driest and warmest places in Ireland. It receives only about 60% the rainfall of the west coast. In addition because Wicklow is protected by the mountains from southwesterly and westerly winds, it enjoys higher average temperatures than much of Ireland. Its average high in August of 21.2 °C (70.2 °F) is a full 1 °C higher than the highest average month in Dublin, only 50 km (30miles) to the north.

While its location is favorable for protection against the prevailing westerly and southwesterly winds that are common to much of Ireland, Wicklow is particularly exposed to easterly winds. As these winds come from the northern European landmass Wicklow can, along with much of the east coast of Ireland, experience relatively sharp temperature drops in winter for short periods.

| Climate data for Ashford, County Wicklow, (5 km north of Wicklow) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 9.2 (48.6) |

9.6 (49.3) |

11.2 (52.2) |

12.9 (55.2) |

15.6 (60.1) |

18.2 (64.8) |

19.5 (67.1) |

21.2 (70.2) |

18.1 (64.6) |

14.8 (58.6) |

11.7 (53.1) |

9.2 (48.6) |

14.2 (57.6) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 2.9 (37.2) |

2.8 (37) |

3.4 (38.1) |

4.7 (40.5) |

6.9 (44.4) |

9.4 (48.9) |

11.2 (52.2) |

11.3 (52.3) |

10 (50) |

7.4 (45.3) |

4.8 (40.6) |

3.1 (37.6) |

6.5 (43.7) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 86 (3.39) |

61.8 (2.433) |

63.6 (2.504) |

60.7 (2.39) |

65.8 (2.591) |

72.1 (2.839) |

67 (2.64) |

69.8 (2.748) |

72.1 (2.839) |

118.9 (4.681) |

110.9 (4.366) |

85.6 (3.37) |

935 (36.81) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1 mm) | 14 | 10 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 9 | 13 | 13 | 11 | 129 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 68.0 | 83.2 | 136.8 | 180.4 | 204.0 | 189.4 | 163.2 | 158.5 | 135.9 | 103.3 | 83.8 | 65.9 | 1,572.4 |

| Source #1: Met Éireann | |||||||||||||

| Source #2: Ashford Weather Station,[4] | |||||||||||||

Economy

Since 1995, the town has undergone significant change and expansion reflecting the simultaneous growth in the Irish economy. Considerable residential development has taken place to the west of the town along Marlton Road (R751). More recently, housing developments have been concentrated to the northwest of the town towards the neighbouring village of Rathnew. The completion of the Ashford/Rathnew bypass in 2004 has meant that Wicklow is now linked to the capital, Dublin, lying 42 km to the north, by dual carriageway and motorway. These factors have led to a steady growth in population of Wicklow and its surrounding townlands while its importance as a commuter town to Dublin increases.

Toponymy

Earlier spellings of the town's name include Wykinglo in 1173, Wygingelow in 1185, Wykinglo in 1192, Wykinglowe in 1355.[5][6]

The Swedish toponymist Magne Oftedal[7] criticises the usual explanation that the name comes from Old Norse Vikingr (meaning "Viking") and Old Norse ló (meaning "meadow"), that is to say "the Vikings' meadow" or "Viking's meadow". He notices that -lo was never used outside Norway (cf. Oslo) and Scandinavia. Furthermore, this word is almost never combined with a male name or a general word meaning "a category of person". Moreover, "Viking" never appears in toponymic records. For him, the first element can be explained as Uikar- or Uik- "bay" in Old Norse and the intermediate N of the old forms is a mistake by the clerks.

However, all recorded forms show this N. That is the reason why Liam Price[8] says it is probably a Norwegian place-name and A. Sommerfelt[9] gives it as a former Vikinga-ló and understands it as "the Vikings' meadow". Nevertheless, the Irish patronimics Ó hUiginn and Mac Uiginn (anglicised O'Higgins and Maguigan) could bring a key for the meaning "Meadow of a man called Viking".[10]

Wykinglo was the usual name used by the Viking sailors and the traders who travelled around the Anglo-Scandinavian world. The Normans and Anglo-Normans who conquered Ireland preferred the non-Gaelic placename.

The origin of the Irish name Cill Mhantáin bears no relation to the name Wicklow. It has an interesting folklore of its own. Saint Patrick and some followers are said to have tried to land on Travailahawk beach, to the south of the harbour. Hostile locals attacked them, causing one of Patrick's party to lose his front teeth. Manntach (toothless one), as he became known, was undeterred and returned to the town, eventually founding a church.[11] Hence Cill Mhantáin, meaning "church of the toothless one". Although its anglicised spelling Kilmantan[12] was used for a time, it gradually fell out of use.

History

During excavations to build the Wicklow road bypass in 2010, a Bronze Age cooking pit (Fulach Fiadh) and hut site was uncovered in the Ballynerrn Lower area of the town. A radio carbon-dating exercise on the site puts the timeline of the discovery at 900 BC.[13] The first Celts arrived in Ireland around 600 BC. According to the Greek cartographer and historian, Ptolemy, the area around Wicklow was settled by a Celtic tribe called the Cauci/Canci. This tribe is believed to have originated in the region containing today's Belgium/German border. The area around Wicklow was referred to as Menapia in Ptolemy's map which itself dates back to 130 AD.[13]

Vikings landed in Ireland around 795 AD and began plundering monasteries and settlements for riches and to capture slaves. In the mid-9th century, Vikings established a base which took advantage of the natural harbour at Wicklow. It is from this chapter of Wicklow's history that the name 'Wicklow' originates.[13]

The Norman influence can still be seen today in some of the town's place and family names. After the Norman invasion, Wicklow was granted to Maurice FitzGerald who set about building the 'Black Castle', a land-facing fortification that lies ruined on the coast immediately south of the harbour. The castle was briefly held by the local O'Byrne, the O'Toole and Kavanagh clans[14] in the uprising of 1641 but was quickly abandoned when English troops approached the town. Sir Charles Coote, who led the troops is then recorded as engaging in "savage and indiscriminate" slaughter of the townspeople in an act of revenge.[15] Local oral history contends that one of these acts of "wanton cruelty" was the entrapment and deliberate burning to death of an unknown number of people in a building in the town. Though no written account of this particular detail of Coote's attack on Wicklow is available, a small laneway, locally referred to as "Melancholy Lane", is said to have been where this event took place.

Though the surrounding County of Wicklow is rich in bronze age monuments, the oldest surviving settlement in the town is the ruined Franciscan Abbey. This is located at the west end of Main Street, within the gardens of the local Roman Catholic parish grounds. Other notable buildings include the Town Hall and the Gaol, built in 1702 and recently renovated as a heritage centre and tourist attraction. The East Breakwater, arguably the most important building in the town, was built in the early 1880s by Wicklow Harbour Commissioners. The architect was William George Strype and the builder was John Jackson of Westminster. The North Groyne was completed by about 1909 – John Pansing was the designer and Louis Nott of Bristol the builder. Wicklow Gaol was a place of execution up to the end of the 19th century and it was here that Billy Byrne, a leader of the 1798 rebellion, met his end in 1799. He is commemorated by a statue in the town square. The gaol closed in 1924 and is today a tourist attraction with living displays and exhibits.[16]

At Fitzwilliam Square in the centre of Wicklow town is an obelisk commemorating the career of Captain Robert Halpin, commander of the telegraph cable ship Great Eastern, who was born in Wicklow in 1836.[17]

Transport

Bus Éireann and Irish Rail both operate through the town. Bus Éireann provides an hourly which is half-hourly at peak-time service to Dublin City Centre and Airport.Also a service is operated twice daily to Arklow via Rathdrum.

- Route 133 Wicklow (Monument)-Dublin Airport via Grand Hotel, Wicklow Community College, Lidl, Rathnew, Ashford, Newcastle Hospital, Newtownmountkennedy, Garden Village, Kilpedder, Glen of the Downs, Kilmacanogue, Ballywaltrim, Bray, Loughlinstown Hospital, N11, UCD Belfield, RTÉ, Donnybrook Village, Leeson Street, Dawson Street/Kildare Street, City Quays en route to Dublin Airport.[18]

- Route 133 Wicklow (Monument)-Arklow via Grand Hotel, Wicklow Community College, Lidl, Rathnew, Glenealy, Rathdrum, Meeting Of The Waters, Avoca and Woodenbridge en route to Arklow.[18]

- A train service operates northbound to Dublin Connolly via Kilcoole, Greystones, Bray, Dun Laoghaire, Pearse Street and Tara Street en route to Connolly 6 times on Monday to Fridays.[19]

Trains operate southbound to Rosslare Europort via Rathdrum, Arklow, Gorey, Enniscorthy, Wexford and Rosslare Strand.[19]

Sports and Recreation

Wicklow Golf Club, founded in 1904, is located between the town and Wicklow head, while Blainroe Golf Club is situated about 3.5 km south of Wicklow.

International relations

Wicklow has town twinning agreements with:

- Montigny-le-Bretonneux, France[20]

- Porthmadog, Wales

- Eichenzell, Germany

Notable residents

- Robert Halpin, (b. 1836) Captain of the Brunel-designed SS Great Eastern which laid the transatlantic telegraph cable in the late 19th century

- F. E. Higgins, writer and former resident of Wicklow[21]

See also

References

- ↑ DeAngelis, Camille (2007). Moon Handbooks: Ireland. Avalon Travel Publishing. p. 111. ISBN 1-59880-048-5. Retrieved 15 April 2013.

- ↑ Seán Connors. Mapping Ireland: from kingdoms to counties, Mercier Press, 2001, ISBN 1-85635-355-9, p45

- ↑ "Wicklow Legal Town Results". Central Statistics Office. 2011. Retrieved 5 August 2012.

- ↑ "Wicklow Weather". Ashford Weather Station.

- ↑ Liam Price, The Place-Names of the Barony of Newcastle, p. 171.

- ↑ Donall Mac Giolla Easpaig, L'influence scandinave sur la toponymie irlandaise in L'héritage maritime des Vikings en Europe en l'ouest, Colloque international de la Hague, Presses universitaire de Caen 2002. p. 467 et 468. Translation Jacques Tranier.

- ↑ Scandinavian Place-Names in Ireland in Proceedings of the Seventh Viking Congress (Dublin 1973), B. Alquist and D. Greene Editions, Dublin, Royal Irish Academy 1976. p. 130.

- ↑ Price p. 172.

- ↑ The English forms of the Names of the Main Provinces of Ireland, in Lochlann. A Review of Celtic Studies. IA. Sommerfelt Editions, Trad. ang. of Oslo University Press 1958. p. 224.

- ↑ Mac Giolla Easpaig p. 468

- ↑ The Annals of Clonmacnoise, being annals of Ireland from the earliest period to A.D. 1408. Mageoghagan, Conell & Murphy, Dennis, 1896, p. 66.

- ↑ "Wicklow: Archival records". Placenames Database of Ireland Logainm.ie. Retrieved 15 April 2013.

- 1 2 3 John Finlay (2013). Footsteps Through Wicklow's Past.

- ↑ Wills, James Lives of illustrious and distinguished Irishmen. MacGregor, Polson, 1840, p. 449.

- ↑ Wills, James Lives of illustrious and distinguished Irishmen. MacGregor, Polson, 1840, p. 448.

- ↑ S Shepherd; et al. (1992). Illustrated guide to Ireland. Reader's Digest.

- ↑ The illustrated road book of Ireland. Automobile Association. 1970.

- 1 2 http://www.buseireann.ie/pdf/1367495369-133.pdf

- 1 2 http://www.irishrail.ie/media/08-dublinrosslareeuroport250920131.pdf?v=gchdrpe

- ↑ "Wicklow Town hosted Europe en Scene 2011 – The Year to Volunteer". Wicklow County Council. 2012. Retrieved 24 September 2013.

- ↑ "Fiona's new book to again be a favourite". Irish Independent. 27 March 2008. Retrieved 4 October 2013.

Bibliography

- Cleary, J and O'Brien, A (2001) Wicklow Harbour: A History, Wicklow Harbour Commissioners

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Wicklow. |

- Wicklow Tourism page on Wicklow Town

- Wicklow Chamber of Commerce

- History of Wicklow Town in MP3 format

- Wicklow Mountains National Park

- Wicklow Walks

.jpg)