White League

| White League | |

|---|---|

|

White Man's League Participant in the Reconstruction Era | |

|

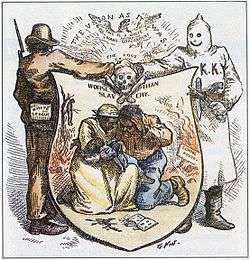

White League and Ku Klux Klan alliance, in illustration, by Thomas Nast, in Harper's Weekly, October 24, 1874 | |

| Active | 1874–1876 |

| Ideology | White supremacy |

| Originated as | Confederate Army veterans |

| Became | State militias |

| Allies | U.S. Democratic Party |

| Opponents | U.S. government, U.S. Republican Party, African Americans, Carpetbaggers, Scalawags |

| Battles and wars |

Coushatta massacre Battle of Liberty Place |

The White League, also known as the White Man's League,[1] was an American white paramilitary organization started in 1874 to turn Republicans out of office and intimidate freedmen from voting and political organizing. Affiliated with the Democratic Party, its first chapter was formed in Grant Parish, Louisiana and neighboring parishes, made up of many of the Confederate veterans who had participated in the Colfax massacre in April 1873. Chapters were soon founded in New Orleans and other areas of the state.

The Red Shirts was a similar group that formed chapters in Mississippi and the Carolinas. Active during the later years of Reconstruction, these paramilitary groups were described as "the military arm of the Democratic Party."[2] Through violence and intimidation of blacks and allied whites, their members suppressed Republican voting and contributed to the Democrats' taking control of the Louisiana Legislature in 1876 (and to Democratic control in other southern states).[2]

After white Democrats regained control of the state legislature in 1876, members of the White Leagues were absorbed into the state militias and the National Guard.[3]

History

Although sometimes linked to the secret vigilante groups, the Ku Klux Klan and Knights of the White Camelia, the White League and other paramilitary groups of the later 1870s marked a significant change.[4] They operated openly in communities, solicited coverage from newspapers, and the men's identities were generally known. Similar paramilitary groups were chapters of the Red Shirts, started in Mississippi in 1875 and active also in North and South Carolina. They had explicit political goals to overthrow the Reconstruction government. They directed their activities toward intimidation and removal of Northern and African American Republican candidates and officeholders. Made up of well-armed Confederate veterans, they worked to turn Republicans out of office, disrupt their political organizing, and use force to intimidate and terrorize freedmen to keep them from the polls. Backers helped finance purchases of up-to-date arms: Winchester rifles, Colt revolvers and Prussian needle guns.[4]

Some sources charge the White League with culpability for the Colfax Massacre of 1873, but the organization was not established under that name until March 1874. Christopher Columbus Nash, a Confederate veteran, former prisoner of war at Johnson's Island in Ohio, and the former sheriff of Grant Parish, led companies of white militias at Colfax to turn out Republican officeholders and African Americans defending the courthouse; his forces killed up to 150 African Americans in the Colfax Massacre, an event in which three white men were killed, one possibly by friendly fire.

The first unit of the White League, founded in 1874, was composed of members of Nash's force, mostly Confederate veterans who had participated in the Colfax Massacre.[5] It expressed its purpose to defend a "hereditary civilization and Christianity menaced by a stupid Africanization."[6]

In 1874, White League members murdered Julia Hayden, a 17-year-old African American girl who was working as a schoolteacher in Hartsville, Tennessee.[1]

In his December 1874 State of the Union address, U.S. President Ulysses S. Grant expressed disdain over the White League's activities, condemning them for their violence and for violating the civil rights of freedmen:

I regret to say that with preparations for the late election decided indications appeared in some localities in the Southern States of a determination, by acts of violence and intimidation, to deprive citizens of the freedom of the ballot because of their political opinions. Bands of men, masked and armed, made their appearance; White Leagues and other societies were formed; large quantities of arms and ammunition were imported and distributed to these organizations; military drills, with menacing demonstrations, were held, and with all these murders enough were committed to spread terror among those whose political action was to be suppressed, if possible, by these intolerant and criminal proceedings.

The Coushatta Massacre occurred in another Red River parish: the local White League forced six Republican officeholders to resign and promise to leave the state. The League assassinated the men before they left the parish, together with between five and twenty freedmen (sources differ) who were witnesses. Generally in remote areas, the White League's show of force and outright murders always overcame opposition. They were Confederate veterans, experienced and well armed.[8]

Later in 1874, the Metropolitan Police of New Orleans, established as a state militia by the Republican governor, attempted to intercept a shipment of arms to the League. The League had entered the city to try to take over state government, in the aftermath of the dispute 1872 gubernatorial election. In the subsequent Battle of Liberty Place on September 14, 1874, 5,000 members of the White League routed 3,500 police and state militia to turn out the Republican governor. They demanded the resignation of Governor William Pitt Kellogg in favor of John McEnery, the Democratic candidate. Kellogg refused and the White League briefly fought a battle resulting in 100 casualties. They took over and controlled the State House, City Hall and arsenal for three days, withdrawing just ahead of Federal troops and ships' arriving to reinforce the government. Kellogg had requested aid from U.S. President Ulysses S. Grant; once the troops arrived, he was restored to office.[9]

President Grant sent additional troops within a month in another effort to try to pacify the Red River valley in northern Louisiana. It had been plagued by violence, including the massacres at Colfax in 1873 and Coushatta in 1874.[10] The White League was effective; voting by Republicans decreased and Democrats regained control of the state legislature in 1876.

Legacy

A Battle of Liberty Place Monument was erected in New Orleans in 1891. In December 2016, the city council voted to remove the monument, and its removal was upheld by a federal appeals court in March 2017.[11]

See also

Citations

- 1 2 3 "Louisiana and the Rule of Terror". The Elevator. 10 (26). October 10, 1874. Retrieved August 1, 2015.

Julia Hayden, the colored school teacher, one of the latest victims of the White Man's League, was only seventeen years of age. She was the daughter of respectable parents in Maury County, Tennessee, and had been carefully educated at the Central College, Nashville, a favorite place for the instruction of youth of both sexes of her race. She is said to have possessed unusual personal attractions as well as intelligence. Under the reign of slavery as it is defined and upheld by Davis and Toombs, Julia Hayden would probably have been taken from her parents and sent in a slave coffle to New Orleans to be sold on its auction block. But emancipation had prepared for her a different and less dreadful fate. With that strong desire for mental cultivation which marked the colored race since their freedom, in all circumstances where there is an opportunity left them for its exhibition, the young girl had so improved herself as to become capable of teaching others. She went to Western Tennessee and took charge of a school. Three days after her arrival at Hartsville, at night, two white men, armed with their guns, appeared at the house where she was staying, and demanded the school teacher. She fled, alarmed, to the room of the mistress of the house. The White Leaguers pursued. They fired their guns through the floor of the room and the young girl fell dead within. Her murderers escaped.

- 1 2 Rable, George C. (1984). But There Was No Peace: The Role of Violence in the Politics of Reconstruction. Athens: University of Georgia Press. p. 132.

- ↑ Hogue, James K. (June 2006). The 1873 Battle of Colfax: Para-militarism and Counterrevolution in Louisiana. p. 21.

- 1 2 Nicholas Lemann, Redemption: The Last Battle of the Civil War, New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2007, pp.70-76

- ↑ James K. Hogue, "The Battle of Colfax: Paramilitarism and Counterrevolution in Louisiana", Jun 2006, p. 21

- ↑ Reed, Adolf, Jr. (June 1993). "The battle of Liberty Monument - New Orleans, Louisiana white supremacist statue". The Progressive. Archived from the original on 8 July 2012. Retrieved 18 May 2010.

- ↑ Grant, Ulysses (December 7, 1874) Sixth State of the Union Address

- ↑ Hogue (2006), "The Battle of Colfax", pp. 21-22

- ↑ Nicholas Lemann, Redemption: The Last Battle of the Civil War, New York, Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2006, p.77

- ↑ Nicholas Lemann, Redemption: The Last Battle of the Civil War, New York, Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2006, p.77.

- ↑ Chappell, Bill (7 March 2017). "New Orleans Can Remove Confederate Statues, Federal Appeals Court Says". npr.org. National Public Radio. Retrieved 7 March 2017.

References

- Wall, Bennett H.; et al. (2002). Louisiana: A History. pp. 208–210. ISBN 0-88295-964-6.