White Coke

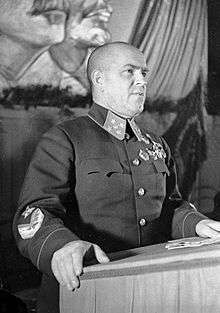

White Coke (Russian: Бесцветная кока-кола, tr. Bestsvetnaya koka-kola) is a nickname for a variant of Coca-Cola produced in the 1940s at the request of Marshal of the Soviet Union Georgy Zhukov.

Zhukov was introduced to Coca-Cola during, or shortly after, World War II by his counterpart in Western Europe, Supreme Commander of Allied Forces in Western Europe, Dwight D. Eisenhower, who was also a fan of the drink.[1]

As Coca-Cola was regarded in the Soviet Union as a symbol of American imperialism,[2] Zhukov was apparently reluctant to be photographed or reported as consuming such a product.

According to journalist Tom Standage (albeit without corroborating sources), Zhukov later asked if Coca-Cola could be manufactured and packaged to resemble vodka.[3]

Marshal Zhukov reportedly made this enquiry through General Mark W. Clark, commander of the US sector of Allied-occupied Austria, who passed the request on to President Harry S. Truman. The President's staff contacted James Farley, chairman of the Board of the Coca-Cola Export Corporation. At the time, Farley was overseeing the establishment of 38 Coca-Cola plants in Southeast Europe, including Austria. Farley delegated Zhukov's special order to Mladin Zarubica, a technical supervisor for the Coca-Cola Company, [4] who had been sent to Austria in 1946 to supervise establishment of a large bottling plant. Zarubica found a chemist who could remove the coloring from Coca-Cola, thereby granting Marshal Zhukov's wish.

The colorless version of Coca-Cola was bottled using straight, clear glass bottles sporting a white cap with a red star in the middle.[5][6] The bottle and the cap were produced by the Crown Cork and Seal Company in Brussels. The first shipment of White Coke consisted of 50 cases.[2][7]

One unusual consequence for the Coca-Cola Company was a relaxation of the regulations imposed by the occupying powers in Austria at the time. That is, Coca-Cola supplies and products were required to transit a Soviet occupation zone, while being transported between the Lambach bottling plant and the Vienna warehouse. While all goods entering the Soviet zone normally took weeks to be cleared by authorities, Coca-Cola shipments were never stopped.[7]

References

- ↑ Cordelia Hebblethwaite (11 September 2012). "Who, What, Why: In which countries is Coca-Cola not sold?". BBC News. Retrieved 12 September 2012.

- 1 2 Mark Pendergrast (15 August 1993). "Viewpoints; A Brief History of Coca-Colonization". The New York Times. Retrieved 12 September 2012.

- ↑ Tom Standage (2006). A History of the World in Six Glasses. Doubleday Canada. p. 256. ISBN 9780385660877. Retrieved 12 September 2012.

- ↑ Mladin Zarubica was the a son of an immigrant to the US from Yugoslavia immigrant, and had been a wartime PT boat commander.

- ↑ Marion Loeb (2 October 2005). "Raise a glass to the civilizing influences of what we drink". The Santa Fe New Mexican. p. 100. Retrieved 12 September 2012.

- ↑ Alfred E. Eckes, Jr; Thomas W. Zeiler (2003). Globalization and the American Century. Cambridge University Press. pp. 118–119. ISBN 9780521009065. Retrieved 25 September 2012.

- 1 2 Mark Pendergrast (2000). For God, Country and Coca-Cola. Basic Books. pp. 210–211. ISBN 9780465054688. Retrieved 25 September 2012.