Spoiler (car)

A spoiler is an automotive aerodynamic device whose intended design function is to 'spoil' unfavorable air movement across a body of a vehicle in motion, usually described as turbulence or drag. Spoilers on the front of a vehicle are often called air dams. Spoilers are often fitted to race and high-performance sports cars, although they have become common on passenger vehicles as well. Some spoilers are added to cars primarily for styling purposes and have either little aerodynamic benefit or even make the aerodynamics worse.

The term "spoiler" is often mistakenly used interchangeably with "wing". An automotive wing is a device whose intended design is to generate downforce as air passes around it, not simply disrupt existing airflow patterns.[1][2] As such, rather than decreasing drag, automotive wings actually increase drag.

Operation

Since spoiler is a term describing an application, the operation of a spoiler varies depending on the particular effect it's trying to spoil. Most common spoiler functions include disrupting some type of airflow passing over and around a moving vehicle. A common spoiler diffuses air by increasing amounts of turbulence flowing over the shape, "spoiling" the laminar flow and providing a cushion for the laminar boundary layer. However, other types of airflow may require the spoiler to operate differently and take on vastly different physical characteristics.

In racing cars

While a mass is travelling at increasing speeds, the air of the environment affects its movement. Spoilers in racing are used in combination with other features on the body or chassis of race cars to change the handling characteristics that are affected by the air of the environment.

Often, these devices are designed to be highly adjustable to suit the needs of racing on a given track or to suit the talents of a particular driver, with the overall goal of reaching faster times.

Passenger vehicles

The goal of many spoilers used in passenger vehicles is to reduce drag and increase fuel efficiency.[3] Passenger vehicles can be equipped with front and rear spoilers. Front spoilers, found beneath the bumper, are mainly used to decrease the amount of air going underneath the vehicle to reduce the drag coefficient and lift.

Sports cars are most commonly seen with front and rear spoilers. Even though these vehicles typically have a more rigid chassis and a stiffer suspension to aid in high speed maneuverability, a spoiler can still be beneficial. This is because many vehicles have a fairly steep downward angle going from the rear edge of the roof down to the trunk or tail of the car which may cause air flow separation. The flow of air becomes turbulent and a low-pressure zone is created, increasing drag and instability (see Bernoulli effect). Adding a rear spoiler could be considered to make the air "see" a longer, gentler slope from the roof to the spoiler, which helps to delay flow separation and the higher pressure in front of the spoiler can help reduce the lift on the car by creating downforce. This may reduce drag in certain instances and will generally increase high speed stability due to the reduced rear lift.

Due to their association with racing, spoilers are often viewed as "sporty" by consumers. However, "the spoilers that feature on more upmarket models rarely provide further aerodynamic benefit."[4]

Material types

.jpg)

Spoilers are usually made of lightweight polymer-based materials, including:

- ABS plastic: Most original equipment manufacturers produce spoilers by casting ABS plastic with various admixtures, typically granular fillers, which introduce stiffness to this inexpensive material. Frailness is a main disadvantage of plastic, which increases with product age and is caused by the evaporation of volatile phenols.

- Fiberglass: Used in car parts production due to the low cost of the materials. Fiberglass spoilers consist of fiberglass cloth infiltrated with a thermosetting resin, such as epoxy. Fiberglass is sufficiently durable and workable, but has become unprofitable for large-scale production because of the labor involved.

- Silicon: More recently, many auto accessory manufacturers are using silicon-organic polymers. The main benefit of this material is its phenomenal plasticity. Silicon possesses extra high thermal characteristics and provides a longer product lifetime.

- Carbon fiber: Carbon fiber is lightweight and durable but also expensive. Due to the large amount of manual labor, large-scale production cannot widely use carbon fiber in automobile parts currently.

Other common spoiler types

- Front spoilers: A front spoiler (air dam) is positioned under or integrated with the front bumper. In racing, this spoiler is used to control the dynamics of handling related to the air in front of the vehicle. This can be to improve the drag coefficient of the body of the vehicle at speed, or to generate downforce. In passenger vehicles, the focus shifts more to directing the airflow into the engine bay for cooling purposes.

- Truck bed spoiler: This attaches only to the top of the truck bed rails near the rear. Used with a bed cover, this spoiler is intended to reduce the air profile of the steep drop-off from the tailgate.

- Truck cab spoiler: This is purposed the same as above, except focusing on the drop-off from the cab of the truck.

Active spoilers

An active spoiler is one which dynamically adjusts while the vehicle is in operation based on conditions presented, changing the spoiling effect, intensity or other performance attribute.

Other vehicles

Heavy trucks, like long haul tractors, may also have a spoiler on the top of the cab in order to lessen drag caused from air resistance from the trailer it's towing, which may be taller than the cab and reduce the aerodynamics of the vehicle dramatically without the use of this spoiler. The trailers they pull can also be fitted with under-side spoilers that angle outward to deflect passing air away from the rear axle's wheels.

Trains may use spoilers to induce drag (like an air brake). A prototype Japanese high-speed train, the Fastech 360 is designed to reach speeds of 400 kilometres per hour (250 mph). Its nose is specifically designed to spoil a wind effect associated with passing through tunnels, and it can deploy 'ears' which act to slow the train in case of emergency by increasing its drag.

Some modern race cars employ a passive situational spoiler called a roof flap. The body of the car is designed to generate downforce while driving forward. These roof flaps deploy when the body of the car is rotated so it is traveling in reverse, a condition where the body instead generates lift. The roof flaps deploy because they are recessed into a pocket in the roof. The low pressure above this pocket will cause the flaps to deploy, and counteract some of the lift generated by the car, making it more resistant to coming out of contact with the ground. These devices were introduced in 1994 in NASCAR following Rusty Wallace's crash at Talladega.[5]

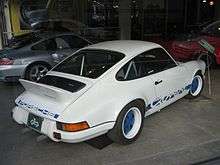

Whale tail

When the Porsche 911 Turbo debuted in August 1974, with large, flared, rear spoilers, they were immediately dubbed whale tails.[6][7][8] Designed to reduce rear-end lift and so keep the car from oversteering at high speeds,[9] the rubber-edges of the whale tail spoilers were thought to be "pedestrian friendly".[10] The Turbo, with its whale tail was popular.[11] It also became one of the world's most recognizable sports cars,[12] remaining in production for the next two decades in one form or another, with more than 23,000 sold by 1989, although from 1978, the rear spoiler was redesigned and dubbed 'teatray' on account of its raised sides.[13] The Porsche 911 whale tails were used in conjunction with a chin spoiler attached to the front valence panel, which, according to some sources, did not enhance aerodynamic stability.[14] It has been found to be less effective in multiplying downforce than newer technologies like an airfoil,[15] "rear wing running across the base of the tailgate window",[16] or "an electronically controlled wing that deploys at about 50 mph".[17] (80 km/h).

History

The whale tail came on the heels of the 1973 "duck tail" or Bürzel in German (as a part of the E-program), a smaller and less flared rear-spoiler fitted to 911 Carrera RS (meaning Rennsport or race sport in German), optional outside Germany.[6][8] The whaletail was originally designed for Porsche 930 and Porsche 935 race cars in 1973, and introduced to the Turbo in 1974 (as a part of the H-program), it was also an option on non-turbo Carreras from 1975.[18][19] Both types of spoilers were designed while Dr. Ernst Fuhrmann was serving as the Technical Director of Porsche AG.[20] In 1976, a rubber front chin spoiler was also introduced to offset the more effective spoiler.[7] By 1978, Porsche introduced another design for the rear spoiler, the "teatray", a boxier enclosure which accommodated the intercooler, and was also an option for the 911SC.[6][21]

Other vehicles

These whale tail car spoilers of the Porsche 911 caught on as a fashion statement,[22] and the term has been used to refer to large rear spoilers on a number of automobiles, including Ford Sierra RS,[23] Focus,[24] Chevrolet Camaro,[25] and Saab 900.[26] Whale tail spoilers also appear at the rear of tricycles,[27] trucks,[28] boats,[29] and other vehicles.

Gallery

This Ford Sierra RS Cosworth has a factory-installed rear spoiler

This Ford Sierra RS Cosworth has a factory-installed rear spoiler- Mitsubishi Lancer Evolution spoiler

.jpg)

Retractable Spoiler on a Bugatti Veyron

Retractable Spoiler on a Bugatti Veyron NASCAR Dodge Charger

NASCAR Dodge Charger

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Automobile spoilers. |

References

- ↑ Katz, Joseph. Race Car Aerodynamics. Bentley Robert. p. 99. ISBN 0837601428.

- ↑ Katz, Joseph. Race Car Aerodynamics. Bentley Robert. pp. 208–209. ISBN 0837601428.

- ↑ "Why a Spoiler for Your Car?: Fuel Economy, Styling, Value Enhancement". Cardata.com. Retrieved 2011-09-28.

- ↑ Happian-Smith, Julian (2000). Introduction to Modern Vehicle Design. Elsevier. p. 116. ISBN 9780080523040. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- ↑ "Jayski's Silly Season Site - Past News Page". Jayski.com. 2005. Retrieved 2013-08-03.

- 1 2 3 Dempsey, Wayne R. (2001). 101 Projects for Your Porsche 911. MotorBooks/MBI Publishing. p. 198. ISBN 0-7603-0853-5.

- 1 2 Anderson, Bruce (1997). Porsche 911 Performance Handbook. MotorBooks/MBI Publishing. p. 16. ISBN 0-7603-0033-X.

- 1 2 Morgan, Peter; Colley, John; Hughes, Mark (1998). Original Porsche 911: The Guide to All Production Models, 1963-98. MotorBooks/MBI Publishing. pp. 144–160. ISBN 1-901432-16-5.

- ↑ Lewis, Albert L.; Musciano, Walter A. (1977). Automobiles of the World. Simon and Schuster. p. 660. ISBN 0-671-22485-9.

- ↑ Paternie, Patrick (2005). Porsche 911 Red Book 1965-2005: 1965-2005. MotorBooks/MBI Publishing. p. 45. ISBN 0-7603-1960-X.

- ↑ Faragher, Scott (2005). Porsche the Ultimate Guide. Krause Publications. p. 50. ISBN 0-87349-720-1.

- ↑ Paternie, Patrick (2005). Porsche 911 Red Book 1965-2005: 1965-2005. MotorBooks/MBI Publishing. p. reface. ISBN 0-7603-1960-X.

- ↑ Anderson, Bruce (1997). Porsche 911 Performance Handbook. MotorBooks/MBI Publishing. p. 16. ISBN 0-7603-0033-X.

- ↑ Dempsey, Wayne R. (2001). 101 Projects for Your Porsche 911: 1964-1989. MotorBooks/MBI Publishing. p. 200. ISBN 0-7603-0853-5.

- ↑ Post, Robert C. (2001). High Performance: The Culture and Technology of Drag Racing, 1950-2000. JHU Press. p. 229. ISBN 0-8018-6664-2.

- ↑ Sturmey, Henry; Staner, H. Walter (1986). The Autocar. Iliffe, Sons & Sturmey. p. 6.

- ↑ (2006). BusinessWeek European Edition: 86. EBSCO Publishing

- ↑ Batchelor, Dean; Leffingwell, Randy (1997). Illustrated Porsche Buyer's Guide. MotorBooks/MBI Publishing. p. 84. ISBN 0-7603-0227-8.

- ↑ Faragher, Scott (2005). Porsche the Ultimate Guide. Krause Publications. p. 49. ISBN 0-87349-720-1.

- ↑ Leffingwell, Randy (2002). Porsche Legends. MotorBooks/MBI Publishing. p. 144. ISBN 0-7603-1364-4.

- ↑ Faragher, Scott (2005). Porsche the Ultimate Guide. Krause Publications. p. 52. ISBN 0-87349-720-1.

- ↑ O'Rourke, P.J. (2000). Holidays in Hell. Grove Press. p. 207. ISBN 0-8021-3701-6.

- ↑ Robson, Graham (2001). The Illustrated Directory of Classic Cars. MotorBooks/MBI Publishing. p. 228. ISBN 0-7603-1049-1.

- ↑ "Car Style First Products used on this Ford Focus". This month's featured car. Car Styling. Retrieved 2008-07-26.

- ↑ "Rear spoilers". Showcars Bodyparts. Retrieved 2008-07-26.

- ↑ "Classic Saab Whale Tail restoration" (PDF). Saab Commemorative Edition Website. Retrieved 2008-07-26.

- ↑ "Hannigan Trikes". EasyCart.net. Retrieved 2008-07-26.

- ↑ "Universal Whale Tail Truck Spoilers". URL.biz. Retrieved 2008-07-26.

- ↑ Perry, Bob. "Classic Swan". Boats.com. Dominion Enterprises. Retrieved 2008-07-26.