African theatre of World War I

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

The African Theatre of World War I describes campaigns in North Africa instigated by the German and Ottoman empires, local rebellions against European colonial rule and Allied campaigns against the German colonies of Kamerun, Togoland, German South West Africa and German East Africa which were fought by German Schutztruppe, local resistance movements and forces of the British Empire, France, Belgium and Portugal.[Note 1]

Background

Strategic situation

German colonies in Africa had been acquired in the 1880s and were not well defended. They were also surrounded by territories controlled by Britain, France, Belgium and Portugal.[3] Colonial military forces in Africa were relatively small, poorly equipped and had been created to maintain internal order, rather than conduct military operations against other colonial forces. Most of the European warfare in Africa during the 19th century had been conducted against African societies to enslave people and later to conquer territory. The Berlin Conference of 1884 had provided for European colonies in Africa to be neutral if war broke out in Europe; in 1914 none of the European powers had plans to challenge their opponents for control of overseas colonies. When news of the outbreak of war reached European colonialists in Africa, it was met by little of the enthusiasm seen in the capital cities of the states which maintained colonies.[4] An editorial in the East African Standard on 22 August argued that Europeans in Africa should not fight each other but instead collaborate, to maintain the repression of the indigenous population. War was against the interest of the white colonialists because they were small in number, many of the European conquests were recent, unstable and operated through existing local structures of power and the organisation of African economic potential for European profit had only recently begun.[4][Note 2]

In Britain, an Offensive sub-committee of the Committee of Imperial Defence was appointed on 5 August and established a principle that command of the seas was to be ensured and that objectives were considered only if they could be attained with local forces and if the objective assisted the priority of maintaining British sea communications, as British army garrisons abroad were returned to Europe in an "Imperial Concentration". Attacks on German coaling stations and wireless stations were considered to be important to clear the seas of German commerce raiders. Objectives at Tsingtau in the Far East and Luderitz Bay, Windhoek, Duala and Dar-es-Salaam in Africa and a German wireless station in Togoland, next to the British colony of Gold Coast in the Gulf of Guinea, were considered vulnerable to attack by local or allied forces.[5]

North Africa

Zaian War, 1914–1921

The Zaian War was fought between France and the Zaian confederation of Berber tribes in Morocco between 1914 and 1921. Morocco had become a French protectorate in 1912 and the French army extended French influence eastwards through the Middle Atlas mountains towards French Algeria. The Zaians, led by Mouha ou Hammou Zayani, quickly lost the towns of Taza and Khénifra but managed to inflict many casualties on the French, who responded by establishing groupes mobiles, combined arms formations that mixed regular and irregular infantry, cavalry and artillery. By 1914 the French had 80,000 troops in Morocco. Two-thirds of the French troops were withdrawn from 1914–1915 for service in France and more than 600 French soldiers were killed at the Battle of El Herri on 13 November 1914. Lyautey, the French governor, reorganised his forces and pursued a forward policy rather than passive defence. The French retained most of their territory despite intelligence and financial support provided by the Central Powers to the Zaian Confederation and raids which caused losses to the French who were already short of manpower.[6]

Senussi campaign, 1915–1917

Coastal campaign, 1915–1916

On 6 November. the German submarine U–35 torpedoed and sank a steamer, HMS Tara, in the Bay of Sollum. U-35 surfaced, sank the coastguard gunboat Abbas and badly damaged Nur el Bahr with its deck gun. On 14 November the Sanussi attacked an Egyptian position at Sollum and on the night of 17 November, a party of Sanussi fired into Sollum, as another party cut the coast telegraph line. Next night a monastery at Sidi Barrani, 48 miles (77 km) beyond Sollum, was occupied by 300 Muhafizia and on the night of 19 November, a coastguard was killed. An Egyptian post was attacked 30 miles (48 km) east of Sollum on 20 November. The British withdrew from Sollum to Mersa Matruh, 120 miles (190 km) further east, which had better facilities for a base, and the Western Frontier Force was created.[7][Note 3]

On 11 December, a British column sent to Duwwar Hussein was attacked along the Matruh–Sollum track and in the Affair of Wadi Senba, drove the Senussi out of the wadi.[9] The reconnaissance continued and on 13 December at Wadi Hasheifiat, the British were attacked again and held up until artillery came into action in the afternoon and forced the Sanussi to retreat. The British returned to Matruh until 25 December and then made a night advance to surprise the Sanussi. At the Affair of Wadi Majid, the Sanussi were defeated but were able to withdraw to the west.[10] Air reconnaissance found more Senussi encampments in the vicinity of Matruh at Halazin, which was attacked on 23 January, in the Affair of Halazin. The Senussi fell back skilfully and then attempted to envelop the British flanks. The British were pushed back on the flanks as the centre advanced and defeated the main body of Senussi, who were again able to withdraw.[11]

In February 1916, the Western Frontier Force was reinforced and a British column was sent west along the coast to re-capture Sollum. Air reconnaissance discovered a Senussi encampment at Agagia, which was attacked in the Action of Agagia on 26 February. The Senussi were defeated and then intercepted by the Dorset Yeomanry as they withdrew; the Yeomanry charged across open ground swept by machine-gun and rifle fire. The British lost half their horses and 58 of 184 men but prevented the Senussi from slipping away. Jaafar Pasha, the commander of the Senussi forces on the coast, was captured and Sollum was re-occupied by British forces on 14 March 1916, which concluded the coastal campaign.[12]

Band of Oases campaign, 1916–1917

On 11 February 1916 Ahmed Sharif as-Senussi, leader of the Senussi order in Cyrenaica, occupied the oasis at Bahariya, which was then bombed by British aircraft. The oasis at Farafra was occupied at the same time and then the Senussi moved on to the oasis at Dakhla on 27 February. The British responded by forming the Southern Force at Beni Suef. Egyptian officials at Kharga were withdrawn and the oasis was occupied by the Senussi, until they withdrew without being attacked. The British reoccupied the oasis on 15 April and began to extend the light railway terminus at Kharga to the Moghara Oasis. The mainly Australian Imperial Camel Corps patrolled on camels and in light Ford cars to cut off the Senussi from the Nile Valley. Preparations to attack the oasis at Bahariya were detected by the Senussi garrison, which withdrew to Siwa in early October. The Southern Force attacked the Senussi in the Affairs in the Dakhla Oasis (17–22 October), after which the Senussi retreated to their base at Siwa.[13]

In January 1917, a British column including the Light Armoured Car Brigade with Rolls-Royce Armoured Cars and three Light Car Patrols was dispatched to Siwa. On 3 February the armoured cars surprised and engaged the Senussi at Girba, who retreated overnight. Siwa was entered on 4 February without opposition but a British ambush party at the Munassib Pass was foiled, when the escarpment was found to be too steep for the armoured cars. The light cars managed to descend the escarpment and captured a convoy on 4 February. Next day the Senussi from Girba were intercepted but managed to establish a post the cars were unable to reach and then warned the rest of the Senussi. The British force returned to Matruh on 8 February and Sayyid Ahmed withdrew to Jaghbub. Negotiations between Sayed Idris and the Anglo-Italians which had begun in late January were galvanised by news of the Senussi defeat at Siwa. At Akramah on 12 April, Idris accepted the British terms and those of Italy on 14 April.[14]

Volta-Bani War

Darfur Expedition, 1916

On 1 March 1916 hostilities began between the Sudanese government and the Sultan of Darfur.[15] The Anglo-Egyptian Darfur Expedition was conducted to forestall an imagined invasion of Sudan and Egypt by the Darfurian leader, Sultan Ali Dinar, which was believed to have been synchronised with a Sanussi advance into Egypt from the west.[16] The Sirdar (commander) of the Egyptian Army organised a force of c. 2,000 men at Rahad, a railhead 200 miles (320 km) east of the Darfur frontier. On 16 March, the force crossed the frontier mounted in lorries from a forward base established at Nahud, 90 miles (140 km) from the border, with the support of four aircraft. By May the force was close to the Darfur capital of El Fasher. At the Affair of Beringia on 22 May, the Fur Army was defeated and the Anglo-Egyptian force captured the capital the next day. Dinar and 2,000 followers had left before their arrival and as they moved south, were bombed from the air.[17]

French troops in Chad who had returned from the Kamerun Campaign prevented a Darfurian withdrawal westwards. Dinar withdrew into the Marra mountains 50 miles (80 km) south of El Fasher and sent envoys to discuss terms but the British believed he was prevaricating and ended the talks on 1 August. Internal dissension reduced the force with Dinar to c. 1,000 men and Anglo-Egyptian outposts were pushed out from El Fasher to the west and southwest after the August rains. A skirmish took place at Dibbis on 13 October and Dinar opened negotiations but was again suspected of bad faith. Dinar fled southwest to Gyuba and a small force was sent in pursuit. At dawn on 6 November the Anglo-Egyptians attacked in the Affair of Gyuba and Dinar's remaining followers scattered. The body of the Sultan was found 1 mile (1.6 km) from the camp.[18] After the expedition, Darfur was incorporated into Sudan.[19]

Kaocen revolt, 1916–1917

Ag Mohammed Wau Teguidda Kaocen (1880–1919), the Amenokal ("Chief") of the Ikazkazan Tuareg confederation, had attacked French colonial forces from 1909. The Sanusiya leadership in the Fezzan oasis town of Kufra declared Jihad against the French colonialists in October 1914. The Sultan of Agadez convinced the French that the Tuareg confederations remained loyal and Kaocen's forces besieged the garrison on 17 December 1916. Kaocen, his brother Mokhtar Kodogo and c. 1,000 Tuareg raiders, armed with rifles and a field gun captured from the Italians in Libya, defeated several French relief columns. The Tuareg seized the main towns of the Aïr, including Ingall, Assodé and Aouderas. Modern northern Niger came under rebel control for over three months. On 3 March 1917, a large French force from Zinder relieved the Agadez garrison and began to recapture the towns. Mass reprisals were taken against the town populations, especially against marabouts, though many were neither Tuareg or rebels. The French summarily killed 130 people in public in Agadez and Ingal. Kaocen fled north and was killed in 1919 by local forces in Mourzouk. Kaocen's brother was killed by the French in 1920 after a revolt he led amongst the Toubou and Fula in the Sultanate of Damagaram was defeated.[20]

Somaliland Campaign, 1914-1918

West Africa

Togoland campaign, 1914

The Togoland Campaign (9–26 August 1914) was a French and British invasion of the German colony of Togoland in west Africa (which became Togo and the Volta Region of Ghana after independence) during the First World War. The colony was invaded on 6 August, by French forces from Dahomey to the east and on 9 August by British forces from Gold Coast to the west. German colonial forces withdrew from the capital Lomé and the coastal province and then fought delaying actions on the route north to Kamina, where a new wireless station linked Berlin to Togoland, the Atlantic and south America. The main British and French force from the neighbouring colonies of Gold Coast and Dahomey advanced from the coast up the road and railway, as smaller forces converged on Kamina from the north.[21]

The German defenders were able to delay the invaders for several days at the battles of Bafilo, Agbeluvhoe and Chra but surrendered the colony on 26 August 1914.[21] In 1916, Togoland was partitioned by the victors and in July 1922, British Togoland and French Togoland were created, as League of Nations mandates.[22] The French acquisition consisted of c. 60 percent of the colony, including the coast. The British received the smaller, less populated and less developed portion of Togoland to the west.[23] The surrender of Togoland marked the beginning of the end for the German colonial empire in Africa.[24]

Kamerun campaign, 1914–1916

By 25 August 1914, British forces in Nigeria had moved into Kamerun towards Mara in the far north, towards Garua in the centre and towards Nsanakang in the south. British forces moving towards Garua under the command of Colonel MacLear were ordered to push to the German border post at Tepe near Garua. The first engagement between British and German troops in the campaign took place at the Battle of Tepe, eventually resulting in German withdrawal.[25] In the far north British forces attempted to take the German fort at Mora but failed and began a siege which lasted until the end of the campaign.[26] British forces in the south attacked Nsanakang and were defeated and almost completely destroyed by German counterattacks at the Battle of Nsanakong.[27] MacLear then pushed his forces further inland towards the German stronghold of Garua, but was repulsed in the First Battle of Garua on 31 August.[28]

In 1915 the German forces, except for those at Mora and Garua, withdrew to the mountains near the new capital of Jaunde. In the spring the German forces delayed or repulsed Allied attacks and a force under Captain von Crailsheim from Garua conducted an offensive into Nigeria and fought the Battle of Gurin.[29] General Frederick Hugh Cunliffe began the Second Battle of Garua in June, which was a British victory.[30] Allied units in northern Kamerun were freed to push into the interior, where the Germans were defeated at the Battle of Ngaundere on 29 June. Cunliffe advanced south to Jaunde but was held up by heavy rains and his force joined the Siege of Mora.[31] When the weather improved, Cunliffe moved further south, captured a German fort at the Battle of Banjo on 6 November and occupied several towns by the end of the year.[32] In December, the forces of Cunliffe and Dobell made contact and made ready to conduct an assault on Jaunde.[33] In this year most of Neukamerun had been fully occupied by Belgian and French troops, who also began to prepare for an attack on Jaunde.[34]

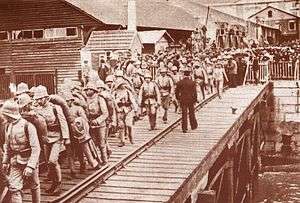

German forces began to cross into the Spanish colony of Rio Muni on 23 December 1915 and with Allied forces pressing in on Jaunde from all sides, the German commander Carl Zimmermann ordered the remaining German units and civilians to escape into Rio Muni. By mid-February, c. 7,000 Schutztruppen and c. 7,000 civilians had reached Spanish territory.[35][36] On 18 February the Siege of Mora ended with the surrender of the garrison.[37] Most Kamerunians remained in Muni but the Germans eventually moved to Fernando Po and some were allowed by Spain to travel to the Netherlands to go home.[38] Some Kamerunians including the paramount chief of the Beti people moved to Madrid, where they lived as visiting nobility on German funds.[39]

Bussa uprising, 1915

Adubi War, 1918

South West Africa

German South West Africa campaign, 1914–1915

An invasion of German South West Africa from the south failed at the Battle of Sandfontein (25 September 1914), close to the border with the Cape Colony. German fusiliers inflicted a serious defeat on the British troops and the survivors returned to British territory.[40] The Germans began an invasion of South Africa to forestall another invasion attempt and the Battle of Kakamas took place on 4 February 1915, between South African and German forces, a skirmish for control of two river fords over the Orange River. The South Africans prevented the Germans from gaining control of the fords and crossing the river.[41] By February 1915, the South Africans were ready to occupy German territory. Botha put Smuts in command of the southern forces while he commanded the northern forces.[42] Botha arrived at Swakopmund on 11 February and continued to build up his invasion force at Walfish Bay (or Walvis Bay), a South African enclave about halfway along the coast of German South West Africa. In March Botha began an advance from Swakopmund along the Swakop valley with its railway line and captured Otjimbingwe, Karibib, Friedrichsfelde, Wilhelmsthal and Okahandja and then entered Windhuk on 5 May 1915.[43]

The Germans offered surrender terms, which were rejected by Botha and the war continued.[42] On 12 May Botha declared martial law and divided his forces into four contingents, which cut off German forces in the interior from the coastal regions of Kunene and Kaokoveld and fanned out into the north-east. Lukin went along the railway line from Swakopmund to Tsumeb. The other two columns rapidly advanced on the right flank, Myburgh to Otavi junction and Manie Botha to Tsumeb and the terminus of the railway.[43] German forces in the north-west fought the Battle of Otavi on 1 July but were defeated and surrendered at Khorab on 9 July 1915.[44] In the south, Smuts landed at the South West African naval base at Luderitzbucht, then advanced inland and captured Keetmanshoop on 20 May. The South Africans linked with two columns which had advanced over the border from South Africa.[45] Smuts advanced north along the railway line to Berseba and on 26 May, after two days' fighting captured Gibeon.[42][46] The Germans in the south were forced to retreat northwards towards Windhuk and Botha's force. On 9 July the German forces in the south surrendered.[43]

Maritz Rebellion, 1914–1915

General Koos de la Rey, under the influence of Siener van Rensburg, a "crazed seer", believed that the outbreak of war foreshadowed the return of the republic but was persuaded by Botha and Smuts on 13 August not to rebel and on 15 August told his supporters to disperse. At a congress on 26 August, De la Rey claimed loyalty to South Africa, not Britain or Germany. The Commandant-General of the Union Defence Force, Brigadier-General Christiaan Frederick Beyers, opposed the war and with the other rebels, resigned his commission on 15 September. General Koos de la Rey joined Beyers and on 15 September they visited Major JCG (Jan) Kemp in Potchefstroom, who had a large armoury and a force of 2,000 men, many of whom were thought to be sympathetic. The South African government believed it to be an attempt to instigate a rebellion. Beyers claimed that it was to discuss plans for a simultaneous resignation of leading army officers, similar to the Curragh incident in Britain.[47]

During the afternoon De la Rey was mistakenly shot and killed by a policeman, at a roadblock set up to look for the Foster gang, and many Afrikaners believed that De la Rey had been assassinated. After the funeral the rebels condemned the war but when Botha asked them to volunteer for military service in South West Africa they accepted.[48] Maritz, at the head of a commando of Union forces on the border of German South West Africa, allied with the Germans on 7 October and issued a proclamation on behalf of a provisional government and declared war on the British on 9 October.[47] Generals Beyers, De Wet, Maritz, Kemp and Bezuidenhout were to be the first leaders of a new South African Republic. Maritz occupied Keimoes in the Upington area. The Lydenburg commando under General De Wet took possession of the town of Heilbron, held up a train and captured government stores and ammunition.[49]

By the end of the week De Wet had a force of 3,000 men and Beyers had gathered c. 7,000 more in the Magaliesberg. General Louis Botha had c. 30,000 pro-government troops.[49] The government declared martial law on 12 October and loyalists under General Louis Botha and Jan Smuts repressed the uprising.[50] Maritz was defeated on 24 October and took refuge with the Germans; the Beyers commando force was dispersed at Commissioners Drift on 28 October, after which Beyers joined forces with Kemp and then was drowned in the Vaal River on 8 December.[49] De Wet was captured in Bechuanaland on 2 December and Kemp, having crossed the Kalahari desert and lost 300 of 800 men and most of their horses on the 1,100-kilometre (680 mi) journey, joined Maritz in German South West Africa and attacked across the Orange river on 22 December. Maritz advanced south again on 13 January 1915 and attacked Upington on 24 January and most of the rebels surrendered on 30 January.[51]

German invasion of Angola, 1914–1915

The campaign in southern Portuguese West Africa (modern-day Angola) took place from October 1914 – July 1915. Portuguese forces in southern Angola were reinforced by a military expedition led by Lieutenant-Colonel Alves Roçadas, which arrived at Moçâmedes on 1 October 1914. After the loss of the wireless transmitter at Kamina in Togoland, German forces in South West Africa could not communicate easily and until July 1915 the Germans did not know if Germany and Portugal were at war (war was declared by Germany on 9 March 1916.). On 19 October 1914, an incident occurred in which fifteen Germans entered Angola without permission and were arrested at fort Naulila and in a mêlée three Germans were killed by Portuguese troops. On 31 October, German troops armed with machine guns launched a surprise attack, which became known as the Cuangar Massacre, on the small Portuguese outpost at Cuangar and killed eight soldiers and a civilian.[52]

On 18 December a German force of 500 men under the command of Major Victor Franke attacked Portuguese forces at Naulila. A German shell detonated the munitions magazine at Forte Roçadas and the Portuguese were forced to withdraw from the Ovambo region to Humbe, with 69 dead, 76 wounded, and 79 troops taken prisoner. The Germans lost 12 soldiers killed and 30 wounded.[53] Local civilians collected Portuguese weapons and rose against the colonial regime. On 7 July 1915, Portuguese forces under the command of General Pereira d'Eça reoccupied the Humbe region and conducted a reign of terror against the population.[54] The Germans retired to the south with the northern border secure during the uprising in Ovambo, which distracted Portuguese forces from operations further south. Two days later German forces in South West Africa surrendered, ending the South West Africa Campaign.[55]

East Africa

East African campaign, 1914–1915

Military operations, 1914–1915

On the outbreak of war there were 2,760 Schutztruppen and 2,319 men in the King's African Rifles in East Africa.[56] On 5 August 1914, British troops from the Uganda Protectorate attacked German outposts near Lake Victoria and on 8 August HMS Astraea and Pegasus bombarded Dar es Salaam.[57] On 15 August, German forces in the Neu Moshi region captured Taveta on the British side of Kilimanjaro.[58] In September, the Germans raided deeper into British East Africa and Uganda and operations were conducted on Lake Victoria by a German boat armed with a QF 1 pounder pom-pom gun. The British armed the Uganda Railway lake steamers SS William Mackinnon, SS Kavirondo, Winifred and Sybil and regained command of Lake Victoria, when two of the British boats trapped the tug, which was then scuttled by the crew. The Germans later raised the tug, salvaged the gun and used the boat as a transport.[59]

The British command planned an operation to suppress German raiding and to capture the northern region of the German colony. Indian Expeditionary Force B of 8,000 troops in two brigades would land at Tanga on 2 November 1914 to capture the city and take control the Indian Ocean terminus of the Usambara Railway. Near Kilimanjaro, Indian Expeditionary Force C of 4,000 men in one brigade, would advance from British East Africa on Neu-Moshi on 3 November, to the western terminus of the railway. After capturing Tanga, Force B would rapidly move north-west to join Force C and mop up the remaining Germans. Although outnumbered 8:1 at Tanga and 4:1 at Longido, the Schutztruppe under Lettow-Vorbeck defeated the British offensive. In the British Official History, C. Hordern wrote that the operation was "... one the most notable failures in British military history".[60]

Chilembwe uprising, 1915

The uprising was led by John Chilembwe, a millenarian Christian minister of the "Watch-Tower" sect, in the Chiradzulu district of Nyasaland (now Malawi) against colonial forced labour, racial discrimination and new demands on the population caused by the outbreak of World War I. Chilembwe rejected co-operation with Europeans in their war, when they withheld property and human rights from Africans.[61] The revolt began in the evening of 23 January 1915, when rebels attacked a plantation and killed three colonists. In another attack early in the morning of 24 January in Blantyre, several weapons were captured.[62] News of the insurrection was received by the colonial government on 24 January, which mobilised the settler militia and two companies of the King's African Rifles from Karonga. The soldiers and militia attacked Mbombwe on 25 January and were repulsed. The rebels later attacked a nearby Christian mission and during the night fled from Mbombwe to Portuguese East Africa.[63] On 26 January government forces took Mbombwe unopposed and Chilembwe was later killed by a police patrol, near the border with Portuguese East African border. In the repression after the rebellion, more than 40 rebels were killed and 300 people were imprisoned.[64]

Naval operations, 1914–1916

Battle of the Rufiji Delta, 1915

A light cruiser, SMS Königsberg of the Imperial German Navy, was in the Indian Ocean when war was declared. Königsberg sank the cruiser HMS Pegasus in Zanzibar harbour and then retired into the Rufiji River delta.[65] After being cornered by warships of the British Cape Squadron, two monitors, HMS Mersey and Severn, armed with 6 in (150 mm) guns, were towed to the Rufiji from Malta by the Red Sea and arrived in June 1915. On 6 July, with extra armour added and covered by a bombardment from the fleet, the monitors entered the river and were engaged by shore-based weapons hidden among trees and undergrowth on 6 July. Two aircraft based at Mafia Island observed the fall of shells, during an exchange of fire at a range of 11,000 yards (10,000 m) with Königsberg, which had assistance from shore-based spotters.[66]

Mersey was hit twice, six crew killed and its gun disabled; Severn was straddled but hit Königsberg several times, before the spotter aircraft returned to base. An observation party was seen in a tree and killed and when a second aircraft arrived both monitors resumed fire. German return fire diminished in quantity and accuracy and later in the afternoon the British ships withdrew. The monitors returned on 11 June and hit Königsberg with the eighth salvo and within ten minutes the German ship could only reply with three guns. A large explosion was seen at 12:52 p.m. At 1:46 p.m. seven explosions occurred. By 2:20 p.m. Königsberg was a mass of flames.[67] The British salvaged six 4 in (100 mm) guns from the Pegasus, which became known as the Peggy guns, and the crew of Königsberg salvaged the 4.1 in (100 mm) main battery guns of their ship and joined the Schutztruppe.[68]

Lake Tanganyika expedition, 1915

The Germans had maintained control of the lake since the outbreak of the war, with three armed steamers and two unarmed motor boats. In 1915, two British motor boats, HMS Mimi and Toutou, each armed with a 3-pounder and a Maxim gun, were transported 3,000 miles (4,800 km) by land to the British shore of Lake Tanganyika. The British captured the German ship Kingani on 26 December, renamed it HMS Fifi and with two Belgian ships, under the command of Commander Geoffrey Spicer-Simson, attacked and sank the German ship Hedwig von Wissmann. The MV Liemba and the Wami, an unarmed motor boat, were the only German ships left on the lake. In February 1916 the Wami was intercepted and run ashore by the crew and burned.[69] Lettow-Vorbeck had the Königsberg gun removed and sent by rail to the main fighting front.[70] Graf von Götzen was scuttled in mid-July after the Belgians made bombing attacks by floatplanes loaned by the British before Belgian colonial troops advancing on Kigoma could capture it; Graf von Götzen was refloated and used by the British.[71] [Note 4]

East African campaign, 1916–1918

Military operations, 1916

General Horace Smith-Dorrien was sent from England to take command of the operations in East Africa but he contracted pneumonia during the voyage and was replaced by General Smuts.[72] Reinforcements and local recruitment had increased the British force to 13,000 South Africans British and Rhodesians and 7,000 Indian and African troops, from a ration strength of 73,300 men which included the Carrier Corps of African civilians. Belgian troops and a larger but ineffective group of Portuguese military units based in Mozambique were also available. During the previous 1915, Lettow-Vorbeck had increased the German force to 13,800 men.[73]

The main attack was from the north from British East Africa, as troops from the Belgian Congo advanced from the west in two columns, over Lake Victoria on the British troop ships SS Rusinga and SS Usoga and into the Rift Valley. Another contingent advanced over Lake Nyasa (now Lake Malawi) from the south-east. Lettow-Vorbeck evaded the British, whose troops suffered greatly from disease along the march. The 9th South African Infantry began the operation in February with 1,135 men and by October it was reduced to 116 fit troops, mostly by disease.[74] The Germans avoided battle and by September 1916, the German Central Railway from the coast at Dar es Salaam to Ujiji had been taken over by the British.[75] As the German forces had been restricted to the southern part of German East Africa, Smuts began to replace South African, Rhodesian and Indian troops with the King's African Rifles and by 1917 more than half the British Army in East Africa was African. The King's African Rifles was enlarged and by November 1918 had 35,424 men. Smuts left in January 1917 to join the Imperial War Cabinet at London.[76]

Belgian-Congolese campaign, 1916

The Belgian Force Publique of 12,417 men formed three groups, each with 7,000–8,000 porters, yet expected to live off the land. The 1915 harvest had been exhausted and the 1916 harvest had not matured; Belgian requisitions alienated the local civilians. On 5 April, the Belgians offered an armistice to the Germans and then on 12 April commenced hostilities.[77] The Force Publique advanced between Kigali and Nyanza under the command of General Charles Tombeur, Colonel Molitor and Colonel Olsen and captured Kigali on 6 May.[77] The Germans in Burundi were forced back and by 17 June the Belgians had occupied Burundi and Rwanda. The Force Publique and the British Lake Force then advanced towards Tabora, an administrative centre of central German East Africa. The Allies moved in three columns and took Biharamulo, Mwanza, Karema, Kigoma and Ujiji. Tabora was captured unopposed on 19 September.[78] To forestall Belgian claims on the German colony, Smuts ordered Belgian forces back to Congo, leaving them as occupiers only in Rwanda and Burundi. The British were obliged to recall Belgian troops in 1917 and after this the Allies coordinated campaign plans.[79]

Military operations, 1917–1918

Major-General J.L. van Deventer began an offensive in July 1917, which by early autumn had pushed the Germans 100 mi (160 km) to the south.[80] From 15–19 October 1917, Lettow-Vorbeck and the British fought a mutually costly battle at Mahiwa, with 519 German casualties and 2,700 British casualties.[81] After the news of the battle reached Germany, Lettow-Vorbeck was promoted to Generalmajor.[82][Note 5] British units forced the Schutztruppe further south and on 23 November, Lettow-Vorbeck crossed into Portuguese Mozambique to plunder supplies from Portuguese garrisons. The Germans marched through Mozambique in caravans of troops, carriers, wives and children for nine months. Lettow-Vorbeck divided the force into three groups, one detachment of 1,000 men under Hauptmann Theodor Tafel, was forced to surrender after running out of food and ammunition, when Lettow and Tafel were unaware they were only one day’s march apart.[84] The Germans returned to German East Africa and then crossed into Northern Rhodesia in August 1918. On 13 November two days after the Armistice was signed in France, the German Army took Kasama unopposed. The next day at the Chambezi River, Lettow-Vorbeck was handed a telegram announcing the signing of the armistice and he agreed to a cease-fire. Lettow-Vorbeck marched his army to Abercorn and formally surrendered on 23 November 1918.[85][Note 6]

Makonbe uprising, 1917

In March 1917 the Makonbe people achieved a measure of social unity and rebelled against the Portuguese colonialists in Zambezia province of Portuguese East Africa (now Mozambique) and defeated the colonial regime; c. 20,000 rebels besieged the Portuguese in Tete. The British refused to lend troops to the Portuguese but 10,000–15,000 Ngoni people were recruited, on the promise of loot, women and children. Through terrorism and slavery, the Portuguese quashed the rebellion by the end of the year. Repercussions of the rising continued as British administrators in Northern Rhodesia in 1918 struggled to compensate local civilians for war service, particularly during the famine of 1917–1918 famine and the Colonial Office banned the coercion of local civilians into British service in the colony, which stranded British troops.[86]

Aftermath

Analysis

The war marked the end of the German colonial empire; during the war the Entente powers posed as crusaders for liberalism and enlightenment but little evidence exists that it was seen as such by Africans. Many African soldiers fought on both sides, with a loyalty to military professionalism rather than nationalism and porters had mainly been attracted by pay or had been coerced. The war had been the final period of the Scramble for Africa; control and annexation of territory had been the principal war aim of the Europeans and the main achievement of Lettow-Vorbeck, had been to thwart some of the ambitions of the South African colonialists.[87] In the post-war settlements, Germany's colonies were divided between Britain, Belgium, Portugal and South Africa. The former German colonies had gained independence by the 1960s except for South West Africa (Namibia) which gained independence from South Africa in 1990.[88]

Casualties

The British Official Historian of the campaigns in "Togo and the Cameroons", F. J. Moberly recorded 927 British casualties, 906 French casualties, the invaliding of 494 out of 807 Europeans and 1,322 out of 11,596 African soldiers. Civilian porters were brought from Allied colonies and of c. 20,000 carriers, 574 were killed or died of disease and 8,219 were invalided as they could be "more easily replaced than soldiers.". Of 10,000–15,000 locally recruited civilians no records were kept. Franco-Belgian troops under the command of General Aymerich had 1,685 killed and 117 soldiers died of disease.[89]

In 2001 Strachan recorded British losses in the East African campaign as 3,443 killed in action, 6,558 died of disease and c. 90,000 deaths among African porters. In South West Africa, Strachan recorded 113 South Africans killed in action and 153 died of disease or accidents. German casualties were 1,188 of whom 103 were killed and 890 were taken prisoner.[90] In 2007 Paice recorded c. 22,000 British casualties in the East African campaign, of whom 11,189 died, 9% of the 126,972 troops in the campaign. By 1917 the conscription of c. 1,000,000 Africans as carriers, had depopulated many districts and c. 95,000 porters had died, among them 20% of the British Carrier Corps in East Africa.[91]

A Colonial Office official wrote that the East African campaign had not become a scandal only ".... because the people who suffered most were the carriers - and after all, who cares about native carriers?"[92] In the German colonies, no records of the number of people conscripted or casualties were kept but in the German Official History, the writer referred to

.... [of] the loss of levies, carriers and boys [sic] [we could] make no overall count due to the absence of detailed sickness records.— Ludwig Boell[92]

Paice referred to a 1989 estimate of 350,000 casualties and a death rate of 1:7 people. Carriers impressed by the Germans were rarely paid and food and cattle were stolen from civilians; a famine caused by the consequent food shortage and poor rains in 1917, led to another 300,000 civilian deaths in Ruanda, Urundi and German East Africa.[93] The impressment of farm labour in British East Africa, the failure of the rains at the end of 1917 and early 1918 led to famine and in September Spanish flu reached sub-Saharan Africa. In British East Africa 160,000–200,000 people died, in South Africa there were 250,000–350,000 deaths and in German East Africa 10–20 percent of the population died of famine and disease; in sub-Saharan Africa, c. 1,500,000–2,000,000 people died in the epidemic.[94]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Liberia declared war on Germany on 4 August 1917.[2]

- ↑ In the short term, colonialist fears of loss of prestige and the consequences of a re-militarisation of Africans were exaggerated. The war increased collaboration between European colonialists and Africans and eroded local social structures, leading to a much slower development of a class of urban, western-educated, politically aware Africans.[4]

- ↑ The Western Frontier Force was composed of three Territorial infantry battalions (1/6th Royal Scots, 2/7th and 2/8th Middlesex Regiment), the 15th Sikhs, three new cavalry regiments formed from the rear details of Yeomanry and Australian Light Horse units who fought at Gallipoli as infantry, Royal Naval Air Service ("RNAS") armoured cars, the 1/1st Nottinghamshire Royal Horse Artillery and two aircraft of 17 Squadron Royal Flying Corps ("RFC"), under the command of Major-General A. Wallace.[8]

- ↑ The ship is still in service as the Liemba, plying the lake under the Tanzanian flag.[71]

- ↑ In early November 1917, the German naval dirigible L.59 travelled over 4,200 mi (6,800 km) in 95 hours but the airship was recalled when beyond Khartoum by the German admiralty, after the British broadcast a spoof signal reporting that Lettow-Vorbeck had surrendered.[83]

- ↑ The Lettow-Vorbeck Memorial marks the spot in Zambia.

Footnotes

- ↑ Tucker 2006, p. 43.

- ↑ Skinner & Stacke 1922, p. 331.

- ↑ Strachan 2001, pp. 495–505.

- 1 2 3 Strachan 2001, p. 496.

- ↑ Moberly 1931, pp. 12–13.

- ↑ Strachan 2001, p. 767.

- ↑ Macmunn & Falls 1928, pp. 106–107.

- ↑ Bostock 1982, p. 28.

- ↑ Skinner & Stacke 1922, p. 210.

- ↑ Macmunn & Falls 1928, pp. 110–113, 113–118.

- ↑ Macmunn & Falls 1928, pp. 119–123.

- ↑ Macmunn & Falls 1928, pp. 123–129.

- ↑ Macmunn & Falls 1928, pp. 135–140.

- ↑ Macmunn & Falls 1928, pp. 140–144.

- ↑ Skinner & Stacke 1922, p. 211.

- ↑ Strachan 2001, pp. 749, 747.

- ↑ Macmunn & Falls 1928, p. 151.

- ↑ Strachan 2001, p. 749.

- ↑ Macmunn & Falls 1928, p. 153.

- ↑ Fuglestad 1973, pp. 82–121.

- 1 2 Moberly 1931, pp. 17–40.

- ↑ Gorman & Newman 2009, p. 629.

- ↑ Louis 2006, p. 217.

- ↑ Strachan 2001, p. 642.

- ↑ Moberly 1931, pp. 73–93.

- ↑ Moberly 1931, pp. 170–173, 228–230, 421.

- ↑ Moberly 1931, pp. 106–109.

- ↑ Moberly 1931, pp. 93–97.

- ↑ Moberly 1931, pp. 268–270.

- ↑ Moberly 1931, pp. 294–299.

- ↑ Moberly 1931, pp. 300–301, 322–323.

- ↑ Moberly 1931, pp. 346–350.

- ↑ Moberly 1931, pp. 388–293.

- ↑ Moberly 1931, pp. 383–384.

- ↑ Moberly 1931, pp. 405–419.

- ↑ Strachan 2001, pp. 538–539.

- ↑ Moberly 1931, p. 421.

- ↑ Moberly 1931, p. 412.

- ↑ Quinn 1973, pp. 722–731.

- ↑ Strachan 2001, pp. 550, 555.

- ↑ Strachan 2001, pp. 550, 552, 554.

- 1 2 3 Tucker & Wood 1996, p. 654.

- 1 2 3 Crafford 1943, p. 102.

- ↑ Strachan 2001, pp. 556–557.

- ↑ Strachan 2001, pp. 559–565.

- ↑ Burg & Purcell 1998, p. 59.

- 1 2 Strachan 2001, p. 551.

- ↑ Strachan 2001, pp. 551–552.

- 1 2 3 Strachan 2001, p. 553.

- ↑ Strachan 2001, p. 552.

- ↑ Strachan 2001, p. 554.

- ↑ Fraga 2010, pp. 127–128.

- ↑ Fraga 2010, p. 128.

- ↑ Strachan 2001, p. 559.

- ↑ Strachan 2001, pp. 558–559.

- ↑ Strachan 2001, pp. 577–579.

- ↑ Miller 1974, p. 42.

- ↑ Miller 1974, p. 43.

- ↑ Miller 1974, p. 195.

- ↑ Hordern 1941, p. 101.

- ↑ Strachan 2001, p. 600.

- ↑ Rotberg 1971, p. 135.

- ↑ Hordern 1941, pp. 179–180.

- ↑ Rotberg 1971, p. 137.

- ↑ Hordern 1941, p. 45.

- ↑ Corbett 1923, pp. 64–65.

- ↑ Corbett 1923, pp. 65–67.

- ↑ Hordern 1941, p. 45, 162.

- ↑ Newbolt 1928, pp. 80–85.

- ↑ Miller 1974, p. 211.

- 1 2 Paice 2007, p. 230.

- ↑ Strachan 2001, p. 602.

- ↑ Strachan 2001, p. 599.

- ↑ Strachan 2001, p. 614.

- ↑ Strachan 2001, p. 618.

- ↑ Strachan 2001, pp. 627–628.

- 1 2 Strachan 2001, p. 617.

- ↑ Strachan 2001, pp. 617–619.

- ↑ Strachan 2001, p. 630.

- ↑ Miller 1974, p. 281.

- ↑ Miller 1974, p. 287.

- ↑ Hoyt 1981, p. 175.

- ↑ Strachan 2001, p. 590.

- ↑ Miller 1974, p. 297.

- ↑ Strachan 2001, p. 641.

- ↑ Strachan 2001, pp. 636, 640.

- ↑ Strachan 2001, p. 643.

- ↑ Strachan 2001, pp. 642–643.

- ↑ Moberly 1931, pp. 424, 426–427.

- ↑ Strachan 2001, pp. 641, 568.

- ↑ Paice 2007, pp. 392–393.

- 1 2 Paice 2007, p. 393.

- ↑ Paice 2007, p. 398.

- ↑ Paice 2007, pp. 393–398.

References

- Books

- Bostock, H. P. (1982). The Great Ride: The Diary of a Light Horse Brigade Scout, World War I. Perth: Artlook Books. OCLC 12024100.

- Burg, D. F.; Purcell, L. E. (1998). Almanac of World War I. Lexington, KY: University of Kentucky. ISBN 0-81312-072-1.

- Corbett, J. S. (1940) [1923]. Naval Operations. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. III (rev. ed.). London: Longmans. ISBN 1-84342-491-6.

- Crafford, F. S. (2005) [1943]. Jan Smuts: A Biography (repr. ed.). Kessinger. ISBN 978-1-4179-9290-4.

- Fraga, L. A. (2010). Do intervencionismo ao sidonismo: os dois segmentos da política de guerra na 1a República, 1916–1918 [Interventionism to Sidonismo the two Segments of War Policy in the First Republic] (in Portuguese). Coimbra: Universidade de Coimbra. ISBN 978-9-89260-034-5.

- Gorman, A.; Newman, A. (2009). Stokes, J., ed. Encyclopaedia of the Peoples of Africa and the Middle East. New York: Facts on File. ISBN 0816071586.

- Hordern, C. (1990) [1941]. Military Operations East Africa: August 1914 – September 1916. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. I (Imperial War Museum & Battery Press ed.). London: HMSO. ISBN 0-89839-158-X.

- Hoyt, E. P. (1981). Guerilla: Colonel von Lettow-Vorbeck and Germany's East African Empire. New York: MacMillan. ISBN 0-02555-210-4.

- Louis, W. R. (2006). Ends of British Imperialism: The Scramble for Empire, Suez and Decolonization: Collected Essays. London: I. B. Tauris. ISBN 1-84511-309-8.

- Macmunn, G.; Falls, C. (1996) [1928]. Military Operations: Egypt and Palestine: From the Outbreak of War with Germany to June 1917. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. I (Imperial War Museum and Battery Press ed.). London: HMSO. ISBN 0-89839-241-1.

- Miller, C. (1974). Battle for the Bundu: The First World War in East Africa. New York: MacMillan. ISBN 0-02584-930-1.

- Moberly, F. J. (1995) [1931]. Military Operations Togoland and the Cameroons 1914–1916. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence (Imperial War Museum and Battery Press ed.). London: HMSO. ISBN 0-89839-235-7.

- Newbolt, H. (2003) [1928]. Naval Operations. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. IV (Imperial War Museum and Naval & Military Press ed.). London: Longmans. ISBN 1-84342-492-4.

- Paice, E. (2009) [2007]. Tip and Run: The Untold Tragedy of the Great War in Africa (Phoenix ed.). London: Weidenfeld & Nicholson. ISBN 978-0-7538-2349-1.

- Rotberg, R. I. (1971). "Psychological Stress and the Question of Identity: Chilembwe's Revolt Reconsidered". In Rotberg, R. I.; Mazrui, A. A. Protest and Power in Black Africa. New York. OCLC 139250.

- Skinner, H. T.; Stacke, H. FitzM. (1922). Principal Events 1914–1918 (PDF). History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence (online ed.). London: HMSO. OCLC 17673086. Retrieved 7 February 2014.

- Strachan, H. (2001). The First World War: To Arms. I. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-926191-1.

- Tucker, S.; Wood, L. M. (1996). The European Powers in the First World War: an Encyclopaedia (Illus. ed.). Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-8153-0399-2.

- Journals

- Fuglestad, F. (1973). "Les révoltes des Touaregs du Niger, 1916–1917" [The Revolts of the Tuareg of Niger, 1916–1917]. Cahiers d'études africaines (in French). Paris, Mouton: Ecole des hautes études en sciences sociales (49). ISSN 0008-0055. (Subscription required (help)).

- Quinn, F. (1973). "An African Reaction to World War I: The Beti of Cameroon". Cahiers d'études africaines. Paris: Éditions EHESS (France). XIII (52). ISSN 1777-5353. (Subscription required (help)).

Further reading

- Books

- Africanus, Historicus (pseud.) (2012). Der 1. Weltkrieg in Deutsch-Südwestafrika 1914/15: Naulila [The First World War in German South West Africa 1914/15: Naulila] (in German). II. Windhoek: Glanz & Gloria Verlag. ISBN 978-99916-872-3-0.

- Clifford, H. C. (1920). The Gold Coast Regiment in the East African Campaign (PDF). London: Murray. OCLC 276295181. Retrieved 8 March 2014.

- Fendall, C. P. (1992) [1921]. The East African Force 1915–1919 (PDF). London: H. F. & G. Witherby. ISBN 0-89839-174-1. Retrieved 25 February 2014.

- Lettow-Vorbeck, P. E. (1920). Meine Erinnerungen aus Ostafrika [My Reminiscences of East Africa] (PDF) (in German) (Hurst and Blackett, London ed.). Leipzig: K. F. Koehler. OCLC 2961551. Retrieved 25 February 2014.

- MacPherson, W. G. (1921). History of the Great War based on Official Documents, Medical Services General History: Medical Services in the United Kingdom; in British Garrisons Overseas and During Operations Against Tsingtau, in Togoland, the Cameroons and South West Africa (PDF). I (1st ed.). London: HMSO. OCLC 769752656. Retrieved 27 February 2014.

- Northrup, D. (1988). Beyond the Bend in the River: African Labor in Eastern Zaire, 1865–1940. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Center for International Studies. ISBN 0-89680-151-9. Retrieved 3 March 2014.

- O'Neill, H. C. (1918). The War in Africa 1914–1917 and in the Far East 1914 (PDF) (1919 ed.). London: Longmans, Green. OCLC 786365389. Retrieved 25 February 2014.

- Pélissier, R. (1977). Les guerres grises: Résistance et revoltes en Angola, 1845–1941 [The Grey Wars: Resistance and Revolts in Angola, 1845-–1941] (in French). Montamets/Orgeval: Éditions Pélissier. OCLC 4265731.

- Strachan, H. (2004). The First World War In Africa. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-925728-0.

- Tucker, S.; Roberts, P. M. (2006). World War I: A Student Encyclopaedia. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-8510-9879-8.

- Waldeck, K. (2010). Gut und Blut für unsern Kaiser: Erlebnisse eines hessischen Unteroffiziers im Ersten Weltrkieg und im Kriegsgefangenenlager Aus in Südwestafrika ["Good and Blood for our Emperor: Experiences of a Hessian Corporal in the First World War and in the Prisoner-of-War Camp in South West Africa"] (in German). Windhoek: Glanz & Gloria Verlag. ISBN 978-99945-71-55-0.

- Journals

- Rotberg, R. I. (March–April 2005). "John Chilembwe: Brief Life of an Anti-colonial Rebel: 1871?–1915". 107 (4). Harvard Magazine. ISSN 0095-2427. Archived from the original on 12 November 2006. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- Theses

- Anderson, R. (2001). World War I in East Africa, 1916–1918 (PhD). University of Glasgow. OCLC 498854094. Retrieved 2 July 2014.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to African theatre of World War I. |

- Liberia from 1912–1920

- Togoland 1914. Harry's Africa. Web. 2012.

- Funkentelegrafie Und Deutsche Kolonien: Technik Als Mittel Imperialistischer Politik. Familie Friedenwald

- Schutzpolizei uniforms

- German Colonial Uniforms