Granulomatosis with polyangiitis

| Granulomatosis with polyangiitis | |

|---|---|

| |

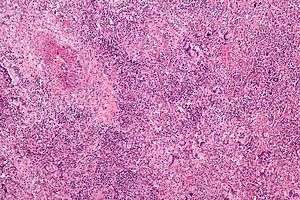

| Micrograph showing features characteristic of granulomatosis with polyangiitis – a vasculitis and granulomas with multi-nucleated giant cells. H&E stain. | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | immunology, rheumatology |

| ICD-10 | M31.3 |

| ICD-9-CM | 446.4 |

| DiseasesDB | 14057 |

| MedlinePlus | 000135 |

| eMedicine | med/2401 |

| Patient UK | Granulomatosis with polyangiitis |

| MeSH | D014890 |

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), previously known as Wegener's granulomatosis (WG), is a systemic disorder that involves both granulomatosis and polyangiitis. It is a form of vasculitis (inflammation of blood vessels) that affects small- and medium-size vessels in many organs. Damage to the lungs and kidneys can be fatal. Treatment requires long-term immunosuppression.[1]

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis is part of a larger group of vasculitic syndromes called systemic vasculitides or necrotizing vasculopathies, all of which feature an autoimmune attack by an abnormal type of circulating antibody termed ANCAs (antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies) against small and medium-size blood vessels. Apart from GPA, this category includes eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA) and microscopic polyangiitis.[1] Although GPA affects small- and medium-size vessels,[2] it is formally classified as one of the small vessel vasculitides in the Chapel Hill system.[3][4]

Signs and symptoms

Initial signs are extremely variable, and diagnosis can be severely delayed due to the nonspecific nature of the symptoms. In general, rhinitis is the first sign in most people.[1][5]

- Kidney: rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis (75%), leading to chronic kidney failure

- Upper airway, eye and ear disease:

- Nose: pain, stuffiness, nosebleeds, rhinitis, crusting, saddle-nose deformity due to a perforated septum

- Ears: conductive hearing loss due to auditory tube dysfunction, sensorineural hearing loss (unclear mechanism)

- Oral cavity: strawberry gingivitis,[6] underlying bone destruction with loosening of teeth, non-specific ulcerations throughout oral mucosa

- Eyes: pseudotumours, scleritis, conjunctivitis, uveitis, episcleritis

- Trachea: subglottal stenosis

- Lungs: pulmonary nodules (referred to as "coin lesions"), infiltrates (often interpreted as pneumonia), cavitary lesions, pulmonary haemorrhage causing haemoptysis, and rarely bronchial stenosis.

- Arthritis: Pain or swelling (60%), often initially diagnosed as rheumatoid arthritis

- Skin: nodules on the elbow, purpura, various others (see cutaneous vasculitis)

- Nervous system: occasionally sensory neuropathy (10%) and rarely mononeuritis multiplex

- Heart, gastrointestinal tract, brain, other organs: rarely affected.

Causes

Its causes are unknown, although microbes, such as bacteria and viruses, as well as genetics have been implicated in its pathogenesis.[5][7]

Pathophysiology

Inflammation with granuloma formation against a nonspecific inflammatory background is the classical tissue abnormality in all organs affected by GPA.[1]

It is now widely presumed that the anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCAs) are responsible for the inflammation in GPA.[1] The typical ANCAs in GPA are those that react with proteinase 3, an enzyme prevalent in neutrophil granulocytes.[8]

In vitro studies have found that ANCAs can activate neutrophils, increase their adherence to endothelium, and induce their degranulation that can damage endothelial cells. In theory, this phenomenon could cause extensive damage to the vessel wall, in particular of arterioles.[1]

Diagnosis

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis is usually suspected only when a person has had unexplained symptoms for a long period of time. Determination of Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCAs) can aid in the diagnosis, but positivity is not conclusive and negative ANCAs are not sufficient to reject the diagnosis. Cytoplasmic-staining ANCAs that react with the enzyme proteinase 3 (cANCA) in neutrophils (a type of white blood cell) are associated with GPA.[1]

If the person has kidney failure or cutaneous vasculitis, a biopsy is obtained from the kidneys. On rare occasions, thoracoscopic lung biopsy is required. On histopathological examination, a biopsy will show leukocytoclastic vasculitis with necrotic changes and granulomatous inflammation (clumps of typically arranged white blood cells) on microscopy. These granulomas are the main reason for the name granulomatosis with polyangiitis, although it is not an essential feature. Nevertheless, necrotizing granulomas are a hallmark of this disease. However, many biopsies can be nonspecific and 50% provide too little information for the diagnosis of GPA.[1]

Criteria

In 1990, the American College of Rheumatology accepted classification criteria for GPA. These criteria were not intended for diagnosis, but for inclusion in randomized controlled trials. Two or more positive criteria have a sensitivity of 88.2% and a specificity of 92.0% of describing GPA.[9]

- Nasal or oral inflammation:

- painful or painless oral ulcers or

- purulent or bloody nasal discharge

- Lungs: abnormal chest X-ray with:

- nodules,

- infiltrates or

- cavities

- Kidneys: urinary sediment with:

- microhematuria or

- red cell casts

- Biopsy: granulomatous inflammation

- within the arterial wall or

- in the perivascular area

According to the Chapel Hill Consensus Conference (CHCC) on the nomenclature of systemic vasculitis (1992), establishing the diagnosis of GPA demands:[10]

- a granulomatous inflammation involving the respiratory tract, and

- a vasculitis of small to medium-size vessels.

Several investigators have compared the ACR and Chapel Hill criteria.[11]

Treatment

The standard treatment for GPA is cyclophosphamide and high dose corticosteroids for remission induction and less toxic immunosuppressants like azathioprine, leflunomide, methotrexate or mycophenolate mofetil.[12] Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole may also help prevent relapse.[12] Rituximab may be substituted for cyclophosphamide in inducing remission.[12][13] A systematic review of 84 trials examined the evidence for various treatments in GPA. Many trials include data on pooled groups of people with GPA and microscopic polyangiitis. In this review, cases are divided between localised disease, non-organ threatening, generalized organ-threatening disease and severe kidney vasculitis and immediately life-threatening disease.[14]

- In generalised non-organ-threatening disease, remission can be induced with methotrexate and steroids, where the steroid dose is reduced after a remission has been achieved and methotrexate used as maintenance.

- In case of organ-threatening disease, pulsed intravenous cyclophosphamide with steroids is recommended. Once remission has been achieved, azathioprine and steroids can be used to maintain remission.

- In severe kidney vasculitis, the same regimen is used but with the addition of plasma exchange.

- In pulmonary haemorrhage, high doses of cyclophosphamide with pulsed methylprednisolone may be used, or alternatively CYC, steroids, and plasma exchange.

Therapy for GPA and MPA has two main components: induction of remission with initial immunosuppressive therapy, and maintenance of remission with immunosuppressive therapy for a variable period to prevent relapse. The mainstay of treatment for granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) is a combination of corticosteroids and cytotoxic agents.

- Medications

- Side effect treatments

- Plasma exchange

- Kidney transplant

Prognosis

Before modern treatments, the 2-year mortality was over 90% and average survival five months.[5][15] Death usually resulted from uremia or respiratory failure.[5]

With corticosteroids and cyclophosphamide, 5-year survival is over 80%.[5] Long-term complications are common (86%), mainly chronic kidney failure, hearing loss and deafness.[1]

Today, drug toxicity is managed more carefully and long-term remissions are possible. Some patients are able to lead relatively normal lives and remain in remission for 20+ years after treatment.[16]

Epidemiology

The incidence is 10–20 cases per million per year.[14][17] It is exceedingly rare in Japan and with African Americans.[17]

History

Scottish otolaryngologist Peter McBride (1854–1946) first described the condition in 1897 in a BMJ article entitled "Photographs of a case of rapid destruction of the nose and face".[18] Heinz Karl Ernst Klinger (born 1907) would add information on the anatomical pathology, but the full picture was presented by Friedrich Wegener (1907–1990), a German pathologist, in two reports in 1936 and 1939,[19] leading to the name Wegener's granulomatosis or Wegener granulomatosis (English: /ˈvɛɡənər/).

An earlier name for the disease was pathergic granulomatosis.[20] The disease is still sometimes confused with lethal midline granuloma and lymphomatoid granulomatosis, both malignant lymphomas.[21]

In 2006, Alexander Woywodt (Preston, United Kingdom) and Eric Matteson (Mayo Clinic, USA) investigated Wegener's past, and discovered that he was, at least at some point of his career, a follower of the Nazi regime. In addition, their data indicate that Wegener was wanted by Polish authorities and that his files were forwarded to the United Nations War Crimes Commission. Furthermore, Wegener worked in close proximity to the genocide machinery in Łódź. Their data raised serious concerns about Wegener's professional conduct. They suggest that the eponym should be abandoned and propose "ANCA-associated granulomatous vasculitis."[22] The authors have since campaigned for other medical eponyms to be abandoned, too.[23] In 2011, the American College of Rheumatology (ACR), the American Society of Nephrology (ASN) and the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) resolved to change the name to granulomatosis with polyangiitis.[24]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Seo P, Stone JH (July 2004). "The antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitides". Am. J. Med. 117 (1): 39–50. PMID 15210387. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.02.030.

- ↑ Gota, CE (May 2013). "Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis (GPA): Vasculitis". Merck Manual Professional. Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp. Retrieved 16 March 2014.

- ↑ Silva, Fred; Jennette, J. Charles; Heptinstall, Robert H.; Olson, Jean T.; Schwartz, Melvin (2007). Hepinstall's pathology of the kidney. Hagerstwon, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 677. ISBN 0-7817-4750-3.

- ↑ Ottoman BAE: Strawberry gingivitis of Wegener’s granulomatosis: A clinicopathological and immunohistochemical study and review of literature.Contemporary Journal immunology: Vol. 2 No. 1 pp. 59-67)

- 1 2 3 4 5 Berden, A; Göçeroglu, A; Jayne, D; Luqmani, R; Rasmussen, N; Bruijn, JA; Bajema, I (January 2012). "Diagnosis and management of ANCA associated vasculitis.". BMJ. 344: e26. PMID 22250224. doi:10.1136/bmj.e26.

- ↑ Ottoman, Bacem (2015). "Strawberry Gingivitis of Wegener’s Granulomatosis: A Clinico-pathological and Immunohistochemical Case Study with Review of Literature". Journal of Contemporary Immunology. doi:10.7726/jci.2015.1004.

- ↑ Tracy, CL; Papadopoulos, PJ; Bye, MR; Connolly, H; Goldberg, E; O'Brian, RJ; Sharma, GD; Talavera, F; Toder, DS; Valentini, RP; Windle, ML; Wolf, RE (10 February 2014). Diamond, HS, ed. "Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Retrieved 16 March 2014.

- ↑ van der Woude FJ, Rasmussen N, Lobatto S, et al. (February 1985). "Autoantibodies against neutrophils and monocytes: tool for diagnosis and marker of disease activity in Wegener's granulomatosis". Lancet. 1 (8426): 425–9. PMID 2857806. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(85)91147-X.

- ↑ Leavitt RY, Fauci AS, Bloch DA, et al. (August 1990). "The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of Wegener's granulomatosis". Arthritis Rheum. 33 (8): 1101–7. PMID 2202308. doi:10.1002/art.1780330807.

- ↑ Jennette JC, Falk RJ, Andrassy K, et al. (February 1994). "Nomenclature of systemic vasculitides. Proposal of an international consensus conference". Arthritis Rheum. 37 (2): 187–92. PMID 8129773. doi:10.1002/art.1780370206.

- ↑ Bruce IN, Bell AL (April 1997). "A comparison of two nomenclature systems for primary systemic vasculitis". Br. J. Rheumatol. 36 (4): 453–8. PMID 9159539. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/36.4.453.

- 1 2 3 Tracy, CL; Papadopoulos, PJ; Bye, MR; Connolly, H; Goldberg, E; O'Brian, RJ; Sharma, GD; Talavera, F; Toder, DS; Valentini, RP; Windle, ML; Wolf, RE (10 February 2014). Diamond, HS, ed. "Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis Treatment & Management". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Retrieved 16 March 2014.

- ↑ Tarabishy, AB; Schulte, M; Papaliodis, GN; Hoffman, GS (September–October 2010). "Wegener's granulomatosis: clinical manifestations, differential diagnosis, and management of ocular and systemic disease.". Survey of Ophthalmology. 55 (5): 429–44. PMID 20638092. doi:10.1016/j.survophthal.2009.12.003.

- 1 2 Bosch X, Guilabert A, Espinosa G, Mirapeix E (2007). "Treatment of antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody associated vasculitis: a systematic review". JAMA. 298 (6): 655–69. PMID 17684188. doi:10.1001/jama.298.6.655.

- ↑ Smith, RM; Jones, RB; Jayne, DR (April 2012). "Progress in treatment of ANCA-associated vasculitis." (PDF). Arthritis Research & Therapy. 14 (2): 210. PMC 3446448

. PMID 22569190. doi:10.1186/ar3797.

. PMID 22569190. doi:10.1186/ar3797. - ↑ "Vasculitis Foundation » Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis (GPA/Wegener’s)". www.vasculitisfoundation.org. Retrieved 2016-03-16.

- 1 2 Cartin-Ceba, R; Peikert, T; Specks, U (December 2012). "Pathogenesis of ANCA-associated vasculitis.". Current Rheumatology Reports. 14 (6): 481–93. PMID 22927039. doi:10.1007/s11926-012-0286-y.

- ↑ Friedmann I (1982). "McBride and the midfacial granuloma syndrome. (The second 'McBride Lecture', Edinburgh, 1980)". The Journal of laryngology and otology. 96 (1): 1–23. PMID 7057076. doi:10.1017/s0022215100092197.

- ↑ synd/2823 at Who Named It?

- ↑ Fienberg R (1955). "Pathergic granulomatosis". Am. J. Med. 19 (6): 829–31. PMID 13275478. doi:10.1016/0002-9343(55)90150-9.

- ↑ Mendenhall WM, Olivier KR, Lynch JW Jr, Mendenhall NP (2006). "Lethal midline granuloma-nasal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma". Am J Clin Oncol. 29 (2): 202–6. PMID 16601443. doi:10.1097/01.coc.0000198738.61238.eb.

- ↑ Woywodt A, Matteson EL (2006). "Wegener's granulomatosis—probing the untold past of the man behind the eponym". Rheumatology (Oxford). 45 (10): 1303–6. PMID 16887845. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/kel258.

- ↑ Woywodt A, Matteson E (2007). "Should eponyms be abandoned? Yes". BMJ. 335 (7617): 424. PMC 1962844

. PMID 17762033. doi:10.1136/bmj.39308.342639.AD.

. PMID 17762033. doi:10.1136/bmj.39308.342639.AD. - ↑ Falk RJ, Gross WL, Guillevin L, et al. (2011). "Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener's): An alternative name for Wegener's granulomatosis". Ann. Rheum. Dis. 70: 74. PMID 21372195. doi:10.1136/ard.2011.150714.