Wayne Morse

| Wayne Morse | |

|---|---|

| |

| United States Senator from Oregon | |

|

In office January 3, 1945 – January 3, 1969 | |

| Preceded by | Rufus C. Holman |

| Succeeded by | Bob Packwood |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Wayne Lyman Morse October 20, 1900 Madison, Wisconsin |

| Died |

July 22, 1974 (aged 73) Portland, Oregon |

| Resting place |

Rest-Haven Memorial Park Eugene, Oregon |

| Nationality | United States |

| Political party |

Republican (1944–1952) Independent (1952–1955) Democratic (1955–1974) |

| Spouse(s) |

Mildred Martha "Midge" Downie Morse (1901–1994) (m. 1924–1974, his death) |

| Children | 3 daughters |

| Parents |

Wilbur F Morse (1859–1936) Jessie Elnora White Morse (1872–1938) |

| Alma mater |

University of Wisconsin (B.A. 1923, M.A. 1924) University of Minnesota (LL.B. 1928) Columbia University (LL.M., S.J.D. 1932) |

| Profession | Attorney |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance |

|

| Service/branch |

|

| Years of service | 1923–1929 |

| Rank |

|

| Unit | Field artillery |

Wayne Lyman Morse (October 20, 1900 – July 22, 1974) was an American politician and attorney of Oregon, known for his proclivity for opposing his parties' leadership, and specifically for his opposition to the Vietnam War on constitutional grounds.[1]

Born in Madison, Wisconsin, and educated at the University of Wisconsin and the University of Minnesota Law School, Morse moved to Oregon in 1930 and began teaching at the University of Oregon School of Law. During World War II, he was elected to the U.S. Senate as a Republican; he became an Independent after Dwight D. Eisenhower's election to the presidency in 1952. While an independent, he set a record for performing the second longest one-person filibuster in the history of the Senate. Morse joined the Democratic Party in 1955, and was reelected twice while a member of that party.

Morse made a brief run for the Democratic Party's presidential nomination in 1960. In 1964, only Morse and Ernest Gruening (D-AK) in the U.S. Senate, opposed the controversial Gulf of Tonkin Resolution. It authorized the president to take military action in Vietnam without a declaration of war. He continued to speak out against the war in the ensuing years, and lost his 1968 bid for reelection to Bob Packwood, who criticized his strong opposition to the war. Morse made two more bids for reelection to the Senate before his death in 1974.

Life before politics

Morse was born on October 20, 1900, in the Madison, Wisconsin, home of his maternal grandparents, Myron and Flora White. Morse's parents, Wilbur F. Morse and Jessie Elnora Morse, farmed a 320-acre (130 ha) plot near Verona, a small community 11 miles (18 km) west-southwest of Madison. Morse grew up on this farm, where the family raised Devon cattle for beef, Percheron and Hackney horses, dairy cows, hogs, sheep, poultry, and feed crops for the animals. The family eventually included five children: Mabel, seven years older than Morse; twin brothers Harry and Grant, four years older; Morse; and Caryl, fourteen years younger.[2]

Encouraged by Jessie, the Morse family held relatively formal nightly discussions about crops, animals, education, religion, and most frequently about politics. Like many of their neighbors, the family was Progressive and discussed ideas championed by Robert M. La Follette, Sr., a leader of the Progressive movement who served as Wisconsin's governor from 1900 to 1906 and thereafter as a member of the U.S. Senate. During these family discussions, Morse developed debating skills and strong opinions about political corruption, corporate domination, labor rights, women's suffrage, education, and, on a personal level, hard work and sobriety.[2]

Morse and his siblings began their education in a one-room school near Verona. However, the Morse parents, particularly Jessie, shared the Progressive belief that improvement of self and society came through good education, and they admired the schools in Madison. After Morse finished second grade, his parents enrolled him in Longfellow School in Madison, to which Morse commuted 22 miles (35 km) round-trip daily by riding relay on three of the family's smaller horses. After eighth grade, Morse attended Madison High School, where he became class president and debating club president, and placed academically among the top 10 in his graduating class. In high school, he developed his relationship with Mildred "Midge" Downie, whom he had known since third grade, and who was class valedictorian and class vice-president the same year Morse was president.[2]

Morse received his bachelor's degree from the University of Wisconsin–Madison in 1923 and his master's, in speech,[3] from Wisconsin the next year.[4] He married Downie in the same year.[3] For several years, he taught speech at the University of Minnesota Law School,[3] and earned his LL.B. degree there in 1928.[4] He held a reserve commission as second lieutenant, Field Artillery, U.S. Army, from 1923 to 1929,[4] and was a member of the Pi Kappa Alpha fraternity.[5]

Morse became an assistant professor of law at the University of Oregon School of Law in 1929.[4] Within nine months, he was promoted to associate professor and then dean of the law school. At age 31, this made him the youngest dean of any law school accredited by the American Bar Association.[6] After becoming a full professor of law in 1931, he completed his S.J.D. (a research doctorate in law equivalent to the Ph.D.) at Columbia Law School in 1932.[6] He served on many public commissions over the following years, including a Roosevelt appointment to settle labor disputes that threatened to halt production of Navy ships during World War II.

Election to the U.S. Senate

In 1944 Morse won the Republican primary election for senator, unseating incumbent Rufus C. Holman, and then the general election that November.[4] Once in Washington, D.C., he revealed his progressive roots, to the consternation of his more conservative Republican peers.[4] He was outspoken in his opposition to the Taft-Hartley Act of 1947, which concerned labor relations.[7]

Morse was reelected in 1950.[4] Earlier in that year, he was one of the six Senators who supported Margaret Chase Smith's Declaration of Conscience, which criticized the tactics of McCarthyism.[8] In protest of Dwight Eisenhower's selection of Richard Nixon as his running mate, Morse left the Republican Party in 1952.[9] The 1952 election produced an almost evenly divided Senate; Morse brought a folding chair when the session convened, intending to position himself in the aisle between the Democrats and Republicans to underscore his lack of party affiliation.[10] Morse expected to retain certain committee memberships but was denied membership on the Labor Committee and others. He used a parliamentary procedure to force a vote of the entire Senate, but lost his bid. Senator Herbert Lehman offered Morse his seat on the Labor Committee, which Morse ultimately accepted.[10]

Following Morse's defection, Republicans had a 48–47 majority; the deaths of nine other senators, and the resignation of another, caused many reversals in control of the Senate during that session.[11] In 1955, Democratic leader Lyndon Johnson persuaded Morse to join the Democratic caucus.[12]

Morse was kicked in the head by a horse in 1951. He sustained major injuries: the kick "tore his lips nearly off, fractured his jaw in four places, knocked out most of his upper teeth, and loosened several others."[13]

In 1953, Morse conducted a filibuster for 22 hours and 26 minutes protesting the Tidelands Oil legislation, which at the time was the longest one-person filibuster in U.S. Senate history (a record surpassed four years later by Strom Thurmond's 24-hour-18-minute filibuster in opposition of the Civil Rights Act of 1957). After a term as an independent, during which he campaigned heavily for Democratic U.S. Senate nominee Richard Neuberger in 1954,[14] Morse switched to the Democratic Party in 1955. Despite these changes in party allegiance, for which he was branded a maverick, Morse won re-election to the United States Senate in 1956. He defeated U.S. Secretary of the Interior and former governor Douglas McKay in a hotly contested race; campaign expenditures totaled over $600,000 between the primary and general elections, a very high amount by contemporary standards.[15] In 1957, Morse voted against the Civil Rights Act of 1957.

In 1959, Morse opposed Eisenhower's appointment of Clare Boothe Luce as ambassador to Brazil. Morse, who had known Luce for many years,[13] chastised Luce for her criticism of Franklin D. Roosevelt.[16] Although the Senate confirmed Luce's appointment in a 79–11 vote, Luce retaliated against him.[16] In her acceptance speech to the Senate, Luce commented that her troubles with Senator Morse were attributable to the injuries he sustained from being kicked by a horse in 1951.[17] She also remarked that riots in Bolivia might be dealt with by dividing the country up among its neighbors.[16] An immediate backlash against these remarks from Morse and other senators, and Luce's refusal to retract the remark about the horse, led to her resignation[13] just three days after her appointment.[18]

Feud with Richard Neuberger

Toward the end of the 1950s, Morse's relationship with Richard Neuberger, the junior senator from Oregon, deteriorated and led to much public feuding. The two had known each other since 1931, when Morse was dean of the University of Oregon law school, and Neuberger was a 19-year-old freshman. Morse befriended Neuberger and often gave him advice, and he used his rhetorical skill to successfully defend Neuberger against charges of academic cheating.[19] After the charges against him were dropped, Neuberger rejected Morse's advice to leave the university and start fresh elsewhere but instead enrolled in Morse's class in criminal law. Morse gave him a "D" in the course and, when Neuberger complained, changed the grade to an "F".[20]

According to Mason Drukman, one of Morse's biographers, even after the two men had become senators, neither could get past what had happened in 1931. "Whatever his accomplishments," Drukman writes, "Neuberger was to Morse a man flawed in character"[21] while Neuberger "could not forgive Morse either for propelling him out of law school ... or for having had to protect him in the honor proceedings."[22] Morse later helped Neuberger, who won his Senate seat in 1954 by only 2,462 votes out of more than a half-million cast, but he also continued to give Neuberger advice that was not always appreciated. "I don't think you should scold me so much," said Neuberger, as quoted by Drukman, in a letter to Morse during the 1954 campaign.[23]

By 1957, the relationship had deteriorated to the point where, rather than talking face-to-face, the senators exchanged angry letters delivered almost daily by messenger between offices in close proximity.[24] Although the letters were private, the feud quickly became public through letters leaked to the press and comments made to colleagues and other third parties, who often had trouble deciding what the fight was about.[25] Drukman describes the feud as a "classic struggle ... of dominating father and rebellious son locked in the age-old fight for supremacy."[26] The feud ended only with Neuberger's death from a stroke in 1960.[27]

1960 run for president

Morse was a late entry in the race for the Democratic nomination for president in 1960. It began unofficially at a 1959 press conference held at the state capitol in Salem by local resident Gary Neal and other Morse supporters. They declared they would put Senator Morse on the ballot by petition.[28] As early as April 1959, Morse told a meeting of the state's Young Democrats that he had no intention of running. The group still voted to advance Senator Morse, after Congresswoman Edith Green introduced him as a favorite son.[29]

Gary Neal was persistent and by winter of 1959 was nearing completion of his signature petition to place Morse on the May ballot. Morse soon found himself at a meeting with Neal where they discussed his efforts. Neal said to Morse, “if we [supporters] don’t put your name on the ballot, your enemies will."[30] It was clear the elephant in the room with Gary Neal and Wayne Morse was the Oregon Republican Party. Morse shot back about the Oregon Republicans, “I say to the Republican Party, trot out your governor. I’m ready to take him on.”[30]

On December 22, 1959, Wayne Morse announced his candidacy for president.[31] He said at his announcement, “Although I would have preferred not to have entered the Oregon race, I shall not run away from a good political fight if it is inevitable.”[31] The Morse for President Oregon Headquarters was located at 353 S.W. Morrison St. Portland, Oregon 97204.[32] The Morse entry into the presidential race did not sit well with many who had anticipated significant campaigning in Oregon from a large field of candidates. Morse was accused of flip-flopping on whether or not he would run.[33]

Morse filed to run in May primaries in the District of Columbia, Maryland, and Oregon, in that order.[34] He had solid connections in all three areas. Oregon was his home and where his wife and family lived. He owned a small farm in Poolesville, Maryland,[35] and had spent fifteen years fighting for D.C. home rule, sponsoring legislation for that cause. Kennedy did not enter the D.C. primary.[36] Senator Hubert Humphrey was Morse's main opponent in the D.C. contest, which Humphrey won 7,831 to 5,866.[36]

Morse had known when he entered the Maryland contest that he was climbing an extremely steep hill, and had hoped to offset a potential loss there with a win in the District. John F. Kennedy was a Catholic and Maryland was the birthplace of the American Catholic church. Morse attempted to generate as much media coverage as possible. The New York Times caught wind of the Morse campaign and did their best to follow Morse around. Morse made his liberalism a key issue at every campaign stop. His remarks in Cumberland, Maryland suggest that Kennedy was anything but a liberal:

When the Eisenhower Administration took office one of its first objectives was to riddle the tax code with favors for big business and it did so with the help of the Senator from Massachusetts. We need a candidate who will reverse the big money and big business domination of government. We need a courageous candidate who will stand up and fight the necessary political battle for the welfare of the average American. Kennedy has never been willing to do that.[37]

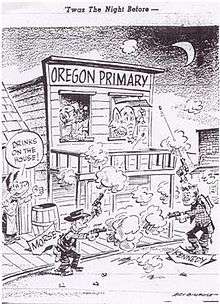

As Morse had predicted, he lost to Kennedy in Maryland. Morse continued to pursue his liberalism strategy as the campaign moved to his home turf. Oregon Democrats prepared for a showdown between Morse and Kennedy, although five candidates would appear on the Oregon ballot. Humphrey, to this point Kennedy's main challenger in the primaries, had lost badly to Kennedy in West Virginia and had dropped out of the race.

The Kennedy campaign began to focus on Oregon. Its workers repeatedly denied that Morse was a serious candidate, but to make sure of a win, the campaign sent Rose Kennedy and Ted Kennedy to speak in Oregon and outspent Morse $54,000 to $9,000.[38] Morse often found himself responding to Kennedy’s claim that he was not a “serious candidate”, by proclaiming: “I’m a dead serious candidate.”[39] Quietly, Oregon Democrats began to worry about what a loss for Morse would mean in 1962 against possible Republican challenger Governor Mark Hatfield. Morse would use this to his advantage to help sway undecided Democrats, claiming that if he lost in the primary, it would certainly help Republicans defeat him in 1962. Kennedy brushed off this argument by claiming that regardless of the outcome of the presidential primary, the people of Oregon had a tremendous respect for Wayne Morse and would send him back to the Senate, and that he would even come back to Oregon in 1962 to campaign for him.[40] On Election Day, Morse came up roughly 50,000 votes short of defeating Kennedy. Morse abandoned his presidential race that same week.[41]

Morse largely sat out the rest of the 1960 campaign. He even opted out of going to the 1960 Democratic National Convention. Instead he sat at home and watched it on television from Eugene.[42]

Senate career 1960–68

In 1964, Morse, who had won re-election in 1962,[9] was one of only two United States senators to vote against the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution (Alaska's Ernest Gruening was the other),[43] which authorized an expansion of U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War. His central contention was that the resolution violated Article One of the United States Constitution, granting the president the ability to take military action in the absence of a formal declaration of war.[44]

During the following years Morse remained one of the country's most outspoken critics of the war. It was later revealed that the FBI investigated Morse based on his opposition to the war, allegedly at the request of President Johnson in an attempt to find information that could be used politically against Morse.[45] In June 1965, Morse joined Benjamin Spock, Coretta Scott King and others in leading a large anti-war march in New York City. After that, Morse "readily joined such protests when he could, and eagerly called upon others to participate."[46]

In the 1966 U.S. Senate election, he angered many in his own party for supporting Oregon's Republican Governor, Mark Hatfield, over the Democratic nominee, Congressman Robert Duncan, in that year's Senate election, due to Duncan's support of the Vietnam War. Hatfield won that race, and Duncan then challenged Morse in the 1968 Democratic senatorial primary. Morse won renomination, but only by a narrow margin. Morse lost his seat in the 1968 general election to State Representative Bob Packwood, who criticized Morse's opposition to continued funding of the war as being reckless, and as distracting him from other issues of importance to the state.[44] Packwood won by a mere 3,500 votes, less than one half of one percent of the total votes cast.[47]

Post-Senate career

Morse spent most of the remaining years of his life attempting to regain his membership in the U.S. Senate. His first attempt since being defeated in 1968 was in 1972.[4] He won the Democratic primary against his old foe, Robert Duncan. In the general election, he lost to the incumbent Mark Hatfield, the Republican incumbent whom he had endorsed in 1966 over fellow Democrat Duncan because of Hatfield's shared opposition to the war in Vietnam but which had become for Morse, according to his principal biographer, a "dismissible virtue" in 1972.[48] In that same year, following the withdrawal of Thomas Eagleton from the national Democratic ticket, a "mini convention" was called to confirm Sargent Shriver as George McGovern's vice presidential running mate. Although most of the delegates voted for Shriver, Oregon cast 4 of its 34 votes for Morse.[49]

On March 19, 1974, Morse, at age 73, filed the paperwork to seek the Democratic nomination for the Senate seat he had lost six years before.[50] Three other Oregon Democrats filed to run against Morse in the 1974 Democratic primary election on May 28 and made Morse's age a key campaign issue.[51] His most prominent opponent was Oregon Senate President Jason Boe.[52] The New York Times said in an editorial that Morse would serve the state with "fierce integrity if elected".[53] Morse managed to defeat Boe in the primary and began preparing for the general election.

On July 21, 1974, while trying to keep up a busy campaign schedule, Morse was hospitalized at Good Samaritan Hospital in Portland due to kidney failure and was listed in critical condition.[54] He died the next day.[4] An editorial ran in The New York Times stating that death "has deprived the United States Senate of a superb public servant".[55]

The Oregon Democratic Central Committee met in August and nominated State Senator Betty Roberts to replace Morse as the Democratic nominee in the Senate race.[56] Roberts lost to the incumbent Bob Packwood in the fall.

Legacy

Wayne Morse was given a state funeral on July 26, 1974, in the Oregon House of Representatives. His body lay in state in the Capitol rotunda before the funeral. More than 600 people attended the funeral service. Former Senator Eugene McCarthy, Governor Tom McCall, Senator Mark Hatfield and Oregon House Speaker Richard Eymann were all in attendance.[57] Pallbearers included Oregon Congressman Al Ullman and three candidates for Congress, Democrats Les AuCoin, Jim Weaver, and Morse's old rival, Robert B. Duncan, who was running for a seat vacated by Congresswoman Edith Green.

When Congressman AuCoin sought to unseat Senator Packwood 18 years later, he adopted Morse's slogan, "principle above politics".[58] Since 1996, the U.S. Senate seat Morse filled has been held by Ron Wyden who as a 19-year-old, drove Morse in the senator's last campaign.[59] Elected in a special election after Packwood's resignation, Wyden won a full term in 1998 and re-election in 2004, 2010, and 2016.

In 2006, the Wayne L. Morse U.S. Courthouse opened in downtown Eugene. In addition, he was recognized in the Wayne Morse Commons of the University of Oregon's William W. Knight Law Center. Also housed in the University of Oregon Law Center is the Wayne Morse Center for Law and Politics. The Lane County Courthouse in Eugene renovated and rededicated its adjacent Wayne L. Morse Free Speech Plaza in the spring of 2005, complete with a life-size statue and pavers imprinted with quotations.

The Morse family's 27-acre (11 ha) Eugene property and home, Edgewood Farm, is listed on the National Register of Historic Places as the Wayne Morse Farm. The City of Eugene, assisted by a nonprofit corporation, operates the historical park formerly known as Morse Ranch. The City of Eugene officially renamed the park Wayne Morse Family Farm in 2008, following a recommendation by the Wayne Morse Historical Park Corporation Board and Morse family members. The new name is more historically accurate.[60] Wayne L. Morse is interred at Rest Haven Memorial Park in Eugene.[4]

Documentary films

- The Last Angry Man: The Story of America's Most Controversial Senator, documentary film by Christopher Houser and Robert Millis

- Clip from War Made Easy on YouTube, a 2007 documentary film

Electoral history

References

- ↑ Willis, Henry (July 22, 1974). "Morse loses last of many battles". Eugene Register-Guard. Oregon. p. 1A.

- 1 2 3 Drukman, "Chapter 1: Progressive Beginnings", Wayne Morse: A Political Biography, pp. 11–34

- 1 2 3 Drukman, Mason (2008). "Wayne Morse (1900-1974)". The Oregon Encyclopedia.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 "Biographical Directory of the United States Congress". United States Congress. Retrieved 2008-11-11.

- ↑ "Prominent Pikes". Pi Kappa Alpha Fraternity. Retrieved 2008-11-15.

- 1 2 "About Wayne Morse: Early Career". Wayne Morse Center for Law and Politics. Archived from the original on May 17, 2008. Retrieved 2008-11-12.

- ↑ Beik, Mildred A. (2005). Labor Relations. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0-313-31864-6.

- ↑ "Margaret Chase Smith, Republican of Maine". Edward M. Kennedy Institute for the United States Senate.

- 1 2 Senate Historical Office. "Wayne Morse Sets Filibuster Record". United States Senate. Retrieved 2008-11-10.

- 1 2 "1941: Independent Fights for Committee Assignments". 29 May 2014.

- ↑ "membership changes 83rd congress". 30 May 2014.

- ↑ "U.S. Senate: Wayne L. Morse: A Featured Biography". 6 July 2015.

- 1 2 3 Drukman, pp. 317–25

- ↑ Swarthout, John M. (December 1954). "The 1954 Election in Oregon". 7 (4). The Western Political Quarterly: 620–625. JSTOR 442815. doi:10.1177/106591295400700413.

- ↑ Balmer, Donald G. (June 1967). "The 1966 Election in Oregon". 20 (2, Part 2). The Western Political Quarterly: 593–601.

- 1 2 3 Streeter, Stephen M. (October 1994). "Campaigning against Latin American Nationalism: U. S. Ambassador John Moors Cabot in Brazil, 1959-1961". The Americas. 51 (2): 193–218. JSTOR 1007925. doi:10.2307/1007925.

- ↑ Drukman, p. 182

- ↑ Clare Boothe Luce, from bioguide.congress.gov

- ↑ Drukman, pp. 246–47

- ↑ Drukman, "Chapter 9: Dick and Wayne", Wayne Morse: A Political Biography, pp. 240–300

- ↑ Drukman, p. 260

- ↑ Drukman, p. 261

- ↑ Drukman, p. 264

- ↑ Drukman, p. 271

- ↑ Drukman, p. 289

- ↑ Drukman, p. 285

- ↑ Drukman, 297–98

- ↑ “Morse Possible Ballot Entry”, The Oregon Journal, August 2, 1959.

- ↑ “Morse Asks No Ballot: Senator Bucks Petition Move”, The Oregonian, August 22, 1959.

- 1 2 The Associated Press, “Morse Hints Primary Run: Presidential Race Expected”, The Oregonian, October 22, 1959, 6M 20.

- 1 2 The Associated Press, “Oregon’s Solon Set for State Primary Fight”, The Oregonian, December 23, 1959. Front Page.

- ↑ Photo, The Oregonian, April 20, 1960

- ↑ Editorial, “Latest Morse Flip-Flop”, The Oregonian, December 27, 1959

- ↑ Drukman, pp. 326–29

- ↑ Drukman, p. 339

- 1 2 Drukman, p. 328

- ↑ “’Liberalism’ Issue Pressed By Morse”, The New York Times, May 14, 1960

- ↑ Drukman, pp. 329–330

- ↑ Smith, Robert. “Campaign Zeroing On Oregon”, The Oregonian. May 12, 1960.

- ↑ Hughes, Harold.,"Kennedy Asks Voters To Back Candidates Who Can Win", The Oregonian, May 18, 1960

- ↑ “Kennedy Has 50,000 Edge; Morse Quits” The Oregonian. May 22, 1960

- ↑ Smith, Robert. “Morse Plans To Forgo Democratic Convention” The Oregonian. June 6, 1960.

- ↑ Halberstam, David. The Best and the Brightest, 2001 Modern Library Edition, pp. 475–76.

- 1 2 About Wayne Morse - Vietnam War

- ↑ "FBI Investigated Wayne Morse Over Vietnam War Opposition; Johnson Allegedly Ordered Probe of Senator". The Washington Post. July 17, 1988.

- ↑ Drukman, p. 414

- ↑ Myers, Clay. Oregon Blue Book. Salem, Oregon: Office of the Secretary of State, 1970.

- ↑ Drukman, "Chapter 14: A Maverick's Denouement", Wayne Morse: A Political Biography, p. 458

- ↑ Leibenluft, Jacob (2008-09-02). "How To Replace a Vice Presidential Nominee". Slate. Washington Post. Newsweek Interactive Co. LLC. Retrieved 2008-11-26.

- ↑ The New York Times, May 19, 1974

- ↑ Willis, Henny (May 26, 1974). "Four want to battle Packwood". The Register-Guard. Archived from the original on January 25, 2013. Retrieved January 29, 2010.

- ↑ The New York Times, May 28, 1974

- ↑ "Editorial", The New York Times, May 30, 1974

- ↑ The New York Times, July 21, 1974

- ↑ Editorial, The New York Times July 23, 1974

- ↑ The New York Times, August 12, 1974.

- ↑ "Obituary",The New York Times, July 27, 1974.

- ↑ "Rep. AuCoin to Try for Senate.". Associated Press. The New York Times. May 30, 1991.

- ↑ "One Senator's Solution For Health Care Expansion". National Public Radio. January 30, 2010.

- ↑ "The Wayne Morse Ranch Historical Park". MUSE: Museums of Springfield/Eugene. Archived from the original on 2008-05-26. Retrieved 2008-11-12.

Works cited

- Drukman, Mason (1997). Wayne Morse: A Political Biography. Portland, Oregon: Oregon Historical Society Press. ISBN 0-87595-263-1.

Further reading

- Smith, A. Robert (1962). The Tiger in the Senate: Biography of Wayne Morse. Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Company, Inc.

- Manger, William; Wayne Lyman Morse (1965). The Two Americas: Dialogue on Progress and Problems. P.J. Kenedy.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Wayne Lyman Morse. |

- Wayne Morse Center for Law and Politics

- Guide to the Wayne Morse papers at the University of Oregon

- Wayne Morse video from "War Made Easy"

- Audio of various Wayne Morse radio commercials

- News coverage from the night Wayne Morse was hospitalized in 1974 on YouTube

- Transcript: The Gulf of Tonkin and Wayne Morse October 13, 1999

- Pacifica Radio's Wayne Morse 1968 DNC audio clips

- Phone call #1 between Morse and President Johnson

- Phone call #2 between Morse and President Johnson on an education bill

- Morse, Fulbright, and LBJ speak about Vietnam on YouTube

- Morse speaks on giving authority to Make WAR on YouTube

- Wayne Morse interviewed by Mike Wallace on The Mike Wallace Interview May 26, 1957

- Wayne Morse Documentary produced by Oregon Public Broadcasting

- A film clip "Longines Chronoscope with Wayne L Morse" is available at the Internet Archive

- Wayne Morse at Find a Grave

| U.S. Senate | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Rufus C. Holman |

U.S. Senator (Class 3) from Oregon 1945–1969 Served alongside: Guy Cordon, Richard L. Neuberger, Hall S. Lusk, Maurine B. Neuberger, Mark Hatfield |

Succeeded by Bob Packwood |

| Party political offices | ||

| Preceded by Rufus C. Holman |

Republican nominee for United States Senator from Oregon (Class 3) 1944, 1950 |

Succeeded by Douglas McKay |

| Preceded by Howard Latourette |

Democratic nominee for United States Senator from Oregon (Class 3) 1956, 1962, 1968 |

Succeeded by Betty Roberts |

| Preceded by Robert B. Duncan |

Democratic nominee for United States Senator from Oregon (Class 2) 1972 |

Succeeded by Vernon Cook |