Water resources in India

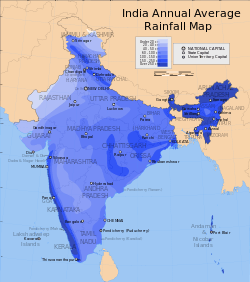

India experiences an average precipitation of 1,170 millimetres (46 in) per year, or about 4,000 cubic kilometres (960 cu mi) of rains annually or about 1,720 cubic metres (61,000 cu ft) of fresh water per person every year.[1] Some 80 percent of its area experiences rains of 750 millimetres (30 in) or more a year. However, this rain is not uniform in time or geography. Most of the rains occur during its monsoon seasons (June to September), with the north east and north receiving far more rains than India's west and south. Other than rains, the melting of snow over the Himalayas after winter season feeds the northern rivers to varying degrees. The southern rivers, however experience more flow variability over the year. For the Himalayan basin, this leads to flooding in some months and water scarcity in others. Despite extensive river system, safe clean drinking water as well as irrigation water supplies for sustainable agriculture are in shortage across India, in part because it has, as yet, harnessed a small fraction of its available and recoverable surface water resource. India harnessed 761 cubic kilometres (183 cu mi) (20 percent) of its water resources in 2010, part of which came from unsustainable use of groundwater.[2] Of the water it withdrew from its rivers and groundwater wells, India dedicated about 688 cubic kilometres (165 cu mi) to irrigation, 56 cubic kilometres (13 cu mi) to municipal and drinking water applications and 17 cubic kilometres (4.1 cu mi) to industry.[1]

Vast area of India is under tropical climate which is conducive throughout the year for agriculture due to favourable warm and sunny conditions provided perennial water supply is available to cater to the high rate of evapotranspiration from the cultivated land.[3] Though the overall water resources are adequate to meet all the requirements of the country, the water supply gaps due to temporal and spatial distribution of water resources are to be bridged by interlinking the rivers.[4] The total water resources going waste to the sea are nearly 1200 billion cubic meters after sparing moderate environmental / salt export water requirements of all rivers.[5] Food security in India is possible by achieving water security first which in turn is possible with energy security to supply the electricity for the required water pumping as part of its rivers interlinking.[6]

Instead of opting for centralised mega water transfer projects which would take long time to give results, it would be cheaper alternative to deploy extensively shade nets over the cultivated lands for using the locally available water sources efficiently to crops throughout the year.[7] Plants need less than 2% of total water for metabolism requirements and rest 98% is for cooling purpose through transpiration. Shade nets or polytunnels installed over the agriculture lands suitable for all weather conditions would reduce the potential evaporation drastically by reflecting the excessive and harmful sun light without falling on the cropped area.

Drought, floods and shortage of drinking water

The precipitation pattern in India varies dramatically across distance and over calendar months. Much of the precipitation in India, about 85%, is received during summer months through monsoons in the Himalayan catchments of the Ganges-Brahmaputra-Meghna basin. The north eastern region of the country receives heavy precipitation, in comparison with the north western, western and southern parts. The uncertainty in onset of annual monsoon, sometimes marked by prolonged dry spells and fluctuations in seasonal and annual rainfall is a serious problem for the country.[8] Large area of the country is not put to use for agriculture due to local water scarcity or poor water quality.[9] The nation sees cycles of drought years and flood years, with large parts of west and south experiencing more deficits and large variations, resulting in immense hardship particularly the poorest farmers and rural populations. Dependence on erratic rains and lack of irrigation water supply regionally leads to crop failures and farmer suicides. Despite abundant rains during July–September, some regions in other seasons see shortages of drinking water. Some years, the problem temporarily becomes too much rainfall, and weeks of havoc from floods.[10]

Surface water and groundwater storages

India currently stores only 6% of its annual rainfall or 253 billion cubic metres (8.9×1012 cu ft), while developed nations strategically store 250% of the annual rainfall in arid river basins.[11] India also relies excessively on groundwater resources, which accounts for over 50 percent of irrigated area with 20 million tube wells installed. India has built nearly 5,000 major or medium dams, barrages, etc. to store the river waters and enhance ground water recharging.[12] The important dams (59 nos) have an aggregate gross storage capacity of 170 billion cubic metres (6.0×1012 cu ft).[13] About 15 percent of India’s food is being produced using rapidly depleting / mining groundwater resources. The end of the era of massive expansion in groundwater use is going to demand greater reliance on surface water supply systems.[14]

Rivers

The major rivers of India are:[15]

- Flowing into the Bay of Bengal: Brahmaputra, Ganges, Mahanadi, Godavari, Krishna, Kaveri, etc.

- Flowing into the Arabian Sea: Indus, Narmada, Tapti, etc.

Lakes

Pulicat Lake, Kolleru Lake, Pangong Tso, Chilika Lake, Kuttanad Lake, Sambhar Salt Lake, Pushkar Lake, etc.

Wetlands

India is a signatory of the Ramsar Convention, an international treaty for the conservation and sustainable utilisation of wetlands[16]

Water supply and sanitation

Water supply and sanitation in India continue to be inadequate, despite long-standing efforts by the various levels of government and communities at improving coverage. The level of investment in water and sanitation, albeit low by international standards, has increased during the 2000s. Access has also increased significantly. For example, in 1980 rural sanitation coverage was estimated at 1% and reached 21% in 2008.[17][18] Also, the share of Indians with access to improved sources of water has increased significantly from 72% in 1990 to 88% in 2008.[17] At the same time, local government institutions in charge of operating and maintaining the infrastructure are seen as weak and lack the financial resources to carry out their functions. In addition, no major city in India is known to have a continuous water supply[19] and an estimated 72% of Indians still lack access to improved sanitation facilities.

In spite of adequate average rainfall in India, there is large area under the less water conditions/drought prone. There are lot of places, where the quality of groundwater is not good. Another issue lies in interstate distribution of rivers. Water supply of the 90% of India’s territory is served by inter-state rivers. It has created growing number of conflicts across the states and to the whole country on water sharing issues.[20]

A number of innovative approaches to improve water supply and sanitation have been tested in India, in particular in the early 2000s. These include demand-driven approaches in rural water supply since 1999, community-led total sanitation, a public-private partnerships to improve the continuity of urban water supply in Karnataka, and the use of micro-credit to women in order to improve access to water.

Water quality issues

When sufficient salt export is not taking place from a river basin to the sea in an attempt to harness the river water fully, it leads to river basin closer and the available water in downstream area of the river basin becomes saline and/ or alkaline water. Land irrigated with saline or alkaline water becomes gradually in to saline or alkali soils.[21][22][23] The water percolation in alkali soils is very poor leading to waterlogging problems. Proliferation of alkali soils would compel the farmers to cultivate rice or grasses only as the soil productivity is poor with other crops and tree plantations.[24] Cotton is the preferred crop in saline soils compared to many other crops as their yield is poor.[25] Interlinking water surplus rivers with water deficit rivers is needed for the long term sustainable productivity of the river basins and for mitigating the anthropogenic influences on the rivers by allowing adequate salt export to the sea in the form of environmental flows.

Water disputes

There is intense competition for the water available in the inter state rivers such as Kavery, Krishna, Godavari, Vamsadhara, Mandovi, Ravi-Beas-Sutlez, Narmada, Tapti, Mahanadi, etc. among the riparian states of India in the absence of water augmentation from the water surplus rivers such as Brahmaputra, Himalayan tributaries of Ganga and west flowing coastal rivers of western ghats.

Water pollution

Out of India's 3,119 towns and cities, just 209 have partial treatment facilities, and only 8 have full wastewater treatment facilities (WHO 1992).[26] 114 cities dump untreated sewage and partially cremated bodies directly into the Ganges River.[27] Downstream, the untreated water is used for drinking, bathing, and washing. This situation is typical of many rivers in India and river Ganga is less polluted comparatively.[28]

Open defecation is widespread even in urban areas of India.[29][30]

Ganges

The Ganges River has been considered one of the dirtiest rivers in the world.[31] The extreme pollution of the Ganges affects 600 million people who live close to the river. The river waters start getting polluted right at the source. The commercial exploitation of the river has risen in proportion to the rise of population. Gangotri and Uttarkashi are good examples too. Gangotri had only a few huts of Sadhus until the 1970s and the population of Uttrakashi has swelled in recent years.

See also

References

- 1 2 "India - Rivers Catchment" (PDF). Retrieved 13 July 2016.

- ↑ Brown, Lester R. (19 November 2013). "India's dangerous 'food bubble'". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 4 December 2013. Retrieved 13 July 2014.

- ↑ "Potential Evapotranspiration estimation for Indian conditions" (PDF). Retrieved 23 June 2016.

- ↑ "India's Water Resources". Retrieved 23 June 2016.

- ↑ IWMI Research Report 83. "Spatial variation in water supply and demand across river basins of India" (PDF). Retrieved 23 June 2016.

- ↑ "India's problem is going to be water not population". Retrieved 21 September 2016.

- ↑ "Protected Cultivation" (PDF). Retrieved 23 June 2016.

- ↑ "How India sees the coming crisis of water — and is preparing for it". Retrieved 30 September 2016.

- ↑ "Waste lands atlas of India, 2011". Retrieved 30 May 2016.

- ↑ "State wise flood damage statistics in India" (PDF). Retrieved 2013-01-04.

- ↑ "Integrated hydrological data book (page 65)" (PDF). Retrieved 29 May 2016.

- ↑ "List of riverwise dams and barrages". Retrieved 29 May 2014.

- ↑ "National register of dams in India" (PDF). Retrieved 19 July 2016.

- ↑ "India’s water economy bracing for a turbulent future, World Bank report, 2006" (PDF). Retrieved 29 May 2014.

- ↑ "River basin maps in India". Retrieved 29 May 2014.

- ↑ "Wet lands atlas of India 2011". Retrieved 29 May 2016.

- 1 2 UNICEF/WHO Joint Monitoring Programme for Water Supply and Sanitation estimate for 2008 based on the 2006 Demographic and Health Survey, the 2001 census, other data and the extrapolation of previous trends to 2010. See JMP tables

- ↑ Planning Commission of India. "Health and Family Welfare and AYUSH : 11th Five Year Plan" (PDF). Retrieved 2010-09-19., p. 78

- ↑ "Development Policy Review". World Bank. Retrieved 2010-09-19.

- ↑ http://greencleanguide.com/2011/07/19/water-scarcity-and-india/

- ↑ J. Keller; A. Keller; G. Davids. "River basin development phases and implications of closure" (PDF). Retrieved 25 May 2016.

- ↑ David Seckler. "The New Era of Water Resources Management: From "Dry" to "Wet" Water Savings" (PDF). Retrieved 5 June 2016.

- ↑ Andrew Keller; Jack Keller; David Seckler. "Integrated Water Resource Systems: Theory and Policy Implications" (PDF). Retrieved 5 January 2014.

- ↑ Oregon State University, USA. "Managing irrigation water quality" (PDF). Retrieved 28 August 2012.

- ↑ "Irrigation water quality—salinity and soil structure stability" (PDF). Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- ↑ Russell Hopfenberg and David Pimentel HUMAN POPULATION NUMBERS AS A FUNCTION OF FOOD SUPPLY oilcrash.com Retrieved on- February 2008

- ↑ National Geographic Society. 1995. Water: A Story of Hope. Washington (DC): National Geographic Society

- ↑ "Water Quality Database of Indian rivers, MoEF". Retrieved 15 September 2016.

- ↑ The Politics of Toilets, Boloji

- ↑ Mumbai Slum: Dharavi, National Geographic, May 2007

- ↑ Salemme, Elisabeth (22 January 2007). "The World's Dirty Rivers". Time. Retrieved 3 May 2010.

External links

- Cook-Anderson, Gretchen (12 August 2009). "NASA Satellites Unlock Secret to Northern India's Vanishing Water". NASA. Retrieved 26 November 2010.

- Children's Eyes on Earth 2012 photography contest – in pictures Peaceful Co-existence Guardian 9 October 2012