Wassily Leontief

| Wassily Leontief | |

|---|---|

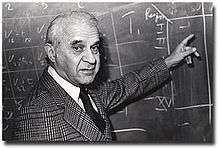

W. W. Leontief at Harvard | |

| Born |

Wassily Wassilyevich Leontief August 5, 1905 Munich, German Empire |

| Died |

February 5, 1999 (aged 92) New York City,[1] United States |

| Citizenship | Russian Empire, Soviet Union, United States |

| Fields | Economics |

| Institutions |

University of Kiel New York University Harvard University |

| Alma mater |

University of Berlin, (PhD) University of Leningrad, (MA) |

| Doctoral advisor |

Ladislaus Bortkiewicz Werner Sombart |

| Doctoral students |

Paul Samuelson Thomas Schelling Robert Solow Kenneth E. Iverson Vernon L. Smith Richard E. Quandt Hyman Minsky Khodadad Farmanfarmaian[2] Dale W. Jorgenson[3] Michael C. Lovell Karen R. Polenske |

| Known for | Input-output analysis |

| Influences | Léon Walras |

| Influenced | George B. Dantzig |

| Notable awards | Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences (1973) |

Wassily Wassilyevich Leontief (Russian: Васи́лий Васи́льевич Лео́нтьев; August 5, 1905 – February 5, 1999), was an American economist known for his research on input-output analysis and how changes in one economic sector may affect other sectors. Leontief won the Nobel Committee's Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences in 1973, and four of his doctoral students have also been awarded the prize (Paul Samuelson 1970, Robert Solow 1987, Vernon L. Smith 2002, Thomas Schelling 2005).

Biography

Early life

Wassily Leontief was born on August 5, 1905, in Munich, Germany, the son of Wassily W. Leontief (professor of Economics) and Zlata (German spelling Slata; later Evgenia) Leontief (née Becker).[4][5] W. Leontief, Sr., belonged to a family of old-believer merchants living in St. Petersburg since 1741.[6] Genya Becker belonged to a wealthy Jewish family from Odessa.[7] At 15 in 1921, Wassily, Jr., entered University of Leningrad in present-day St. Petersburg. He earned his Learned Economist degree (equivalent to Master of Arts) in 1924 at the age of 19.

Opposition in USSR

Leontief sided with campaigners for academic autonomy, freedom of speech and in support of Pitirim Sorokin. As a consequence, he was detained several times by the Cheka. In 1925, he was allowed to leave the USSR, mostly because the Cheka believed that he was mortally ill with a sarcoma, a diagnosis that later proved false.[8] He continued his studies at the University of Berlin and, in 1928 earned a Ph.D. degree in economics under the direction of Werner Sombart, writing his dissertation on The Economy as Circular Flow (original German title: Die Wirtschaft als Kreislauf).

Early professional life

From 1927 to 1930, he worked at the Institute for the World Economy of the University of Kiel. There he researched the derivation of statistical demand and supply curves. In 1929, he traveled to China to assist its ministry of railroads as an advisor.

In 1931, he went to the United States and was employed by the National Bureau of Economic Research.

During World War II, Leontief served as consultant at the U. S. Office of Strategic Services.

Affiliation with Harvard

Leontief joined Harvard University's department of economics in 1932 and in 1946 became professor of economics there.

In 1949, Leontief used an early computer at Harvard and data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics to divide the U.S. economy into 500 sectors. Leontief modeled each sector with a linear equation based on the data and used the computer, the Harvard Mark II, to solve the system, one of the first significant uses of computers for mathematical modeling,[9][10][11] along with George W. Snedecor's usage of the Atanasoff–Berry computer.

Leontief set up the Harvard Economic Research Project in 1948 and remained its director until 1973. Starting in 1965, he chaired the Harvard Society of Fellows.

Affiliation with New York University

In 1975, Leontief joined New York University and founded and directed the Institute for Economic Analysis. He taught graduate and undergraduate classes.

Personal

In 1932, Leontief married poet Estelle Marks. Their only child, Svetlana Leontief Alpers, was born in 1936. Leontief's wife Estelle wrote a memoir, Genia and Wassily, of their relations with his parents after they came to the US as emigres.

As hobbies Leontief enjoyed fly fishing, ballet, and fine wines. He vacationed for years at his farm in West Burke, Vermont, but after moving to New York in the 1970s moved his summer residence to Lakeville, Connecticut.

Leontief died in New York City on Friday, February 5, 1999 at the age of 93. His wife died in 2005.

Major contributions

Leontief is credited with developing early contributions to input-output analysis and earned the Nobel Prize in Economics for his development of its associated theory. He has also made contributions in other areas of economics, such as international trade where he documented the Leontief paradox. He was also one of the first to establish the composite commodity theorem.

Leontief earned the Nobel Prize in economics for his work on input-output tables. Input-output tables analyze the process by which inputs from one industry produce outputs for consumption or for inputs for another industry. With the input-output table, one can estimate the change in demand for inputs resulting from a change in production of the final good. The analysis assumes that input proportions are fixed; thus the use of input-output analysis is limited to rough approximations rather than prediction. Input-output was novel and inspired large-scale empirical work; in 2010 its iterative method was recognized as an early intellectual precursor to Google's PageRank.[12][13][14]

Leontief used input-output analysis to study the characteristics of trade flow between the U.S. and other countries, and found what has been named Leontief's paradox; "this country resorts to foreign trade in order to economize its capital and dispose of its surplus labor, rather than vice versa", i.e., U.S. exports were relatively labor-intensive when compared to U.S. imports. This is the opposite of what one would expect, considering the fact that the U.S.'s comparative advantage was in capital-intensive goods. According to some economists, this paradox has since been explained as due to the fact that when a country produces "more than two goods, the abundance of capital relative to labor does not imply that the capital intensity of its exports should exceed that of imports."[15]

Leontief was also a very strong proponent of the use of quantitative data in the study of economics. Throughout his life Leontief campaigned against "theoretical assumptions and non-observed facts".[15] According to Leontief, too many economists were reluctant to "get their hands dirty" by working with raw empirical facts. To that end, Wassily Leontief did much to make quantitative data more accessible, and more indispensable, to the study of economics.

Publications

- 1925: Баланс народного хозяйства СССР. (“Balans narodnogo khozyaystva SSSR”) in Planovoe Khozyaystvo; translated into Italian in Spulber N.(Ed.) as “Il Bilancio dell’economia nazionale dell’URSS.“ in La Strategia Sovietica per Sviluppo Economico 1924–1930, Giulio Einaudi ed., Torino [discussing the Soviet “Balance of the National Economy”, 1923–4]

- 1928: Die Wirtschaft als Kreislauf, Tübingen: Mohr: re-published as The economy as a circular flow, pp. 181–212 in: Structural Change and Economic Dynamics, Volume 2, Issue 1, June 1991; this translation is abridged to avoid controversial statements.

- 1941: Structure of the American Economy, 1919–1929

- 1953: Studies in the Structure of the American Economy

- 1966: Input-Output Economics

- 1966: Essays in Economics

- 1977: Essays in Economics, II

- 1977: The Future of the World Economy

- 1983: Military Spending: Facts and Figures, Worldwide Implications and Future Outlook co-authed with F. Duchin.

- 1983: The Future of Non-Fuel Minerals in the U. S. And World Economy co-authed with J. Koo, S. Nasar and I. Sohn

- 1986: The Future Impact of Automation on Workers co-authored with F. Duchin

Awards

- 1953: Order of the Cherubim, University of Pisa

- 1962: Dr honoris causa, University of Brussels

- 1967: Dr of the University, University of York

- 1968: Officer of the French Légion d'honneur

- 1970: Bernhard-Harms Prize Economics, West Germany

- 1971: Dr honoris causa, University of Louvain

- 1972: Dr honoris causa, University of Paris (Sorbonne)

- 1973: Bank of Sweden Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel, a.k.a. Nobel Prize in Economics

- 1976: Dr honoris causa, University of Pennsylvania

- 1980: Dr honoris causa, University of Toulouse, France

- 1980: Dr honoris causa, University of Louisville, Kentucky

- 1980: Doctor of Social Sciences, University of Vermont

- 1980: Doctor of Laws, C. W. Post Center, Long Island University

- 1980: Russian-American Hall of Fame

- 1981: Karl Marx University, Budapest, Hungary

- 1984: Order of the Rising Sun, Japan

- 1985: Commandeur, French Order of Arts and Letters

- 1988: Dr honoris causa, Adelphi College

- 1988: Foreign member, USSR Academy of Sciences

- 1989: Society of the Optimate, Italian Cultural Institute, New York

- 1990: Dr honoris causa, University of Córdoba, Spain

- 1991: Takemi Memorial Award, Institute of Seizon & Life Sciences, Japan

- 1995: Harry Edmonds Award for Life Achievement, International House, New York

- 1995: Dr honoris causa, Humboldt University, Berlin, Germany

- Award of Excellence, The International Center in New York

In honor

The Global Development and Environment Institute at Tufts University awards the Leontief Prize in Economics each year in his honor.

Memberships

- 1954: President of the Econometric Society

- 1968: Corresponding Member of the Institut de France

- 1970: President of the American Economic Association

- 1970: Corresponding Fellow of the British Academy

- 1974: US-USSR Commission on the Social Sciences and Humanities of the International Research and Exchanges Board

- 1975: American Committee on East-West Accord

- 1975: Accademia Nazionale dei Lincie, Italy

- 1976: President and Section F. of the British Association for the Advancement of Science

- 1976: Honorary Member of the Royal Irish Academy

- 1977: Fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science

- 1978: Commission to Study the Organization of Peace

- 1978–1986: Board of Trustees of North Carolina School of Science and Mathematics

- 1979: Century Club

- 1979: Issues Committee of the Progressive Alliance

- 1980: Committee for National Security

- 1981: Board of Visitors, College of Liberal Arts, Boston University

- 1981: Board of Editors, Journal of Business Strategy

- 1982: International Advisory Council of the Delian Institute of International Relations

- 1982: Accademia Mediterranea Delle Scienze, Italy

- 1983: Board of Advisors, Environmental Fund

- 1983: Board of Directors, Tolstoy Foundation

- 1985: International Committee, Carnegie Mellon University

- 1990: Academy of Creative Endeavors, USSR

- 1992: International Charitable Foundation, Russia

- 1993: Academie Europeenne

- 1993: Honorary President of the World Academy for the Progress of Planning Science, Italy

- 1993: Member of the Academie Universelle des Cultures, France

- 1994: Fellow of the New York Academy of Sciences

- 1995: Member of the International Leadership Center on Longevity & Society, Mt. Sinai Hospital

- American Philosophical Society

- American Academy of Arts and Sciences

- International Statistical Institute

- Honorary Member of the Japan Economic Research Center, Tokyo

- Honorary Fellow of the Royal Statistical Society, London

- Trustee of Economists for Peace and Security

Quotes

Much of current academic teaching and research has been critizied for its lack of relevance, that is, of immediate practical impact. ... The trouble is caused, however, not by an inadequate selection of targets, but rather by our inability to hit squarely on them, ... by the palpable inadequacy of the scientific means with which they try to solve them. ... The weak and all too slowly growing empirical foundations clearly cannot support the proliferating superstructure of pure, or should I say, speculative economic theory.... By the time it comes to interpretations of the substantive conclusions, the assumptions on which the model has been based are easily forgotten. But it is precisely the empirical validity of these assumptions on which the usefulness of the entire exercise depends. ... A natural Darwinian feedback operating through selection of academic personnel contributes greatly to the perpetuation of this state of affairs.[16]We move from more or less plausible but really arbitrary assumptions, to elegantly demonstrated but irrelevant conclusions.

The role of humans as the most important factor of production is bound to diminish in the same way that the role of horses in agricultural production was first diminished and then eliminated by the introduction of tractors.[17]

See also

References and sources

- ↑

- ↑ http://www.fas.harvard.edu/~iohp/farmanfarmaian.html

- ↑ Jorgenson, Dale W. (1998). Growth, Vol. 1: Econometric General Equilibrium Modeling. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press(Accessed September 2016)

- ↑ See birth data, provided October 4, 2005. In his Nobel Prize website biographical information it states that recent information sets his year of birth to 1905.

- ↑ Bjerkholt, Olav, and Heinz D. Kurz (2006). "Introduction: the History of Input–Output Analysis, Leontief's Path and Alternative Tracks". Economic Systems Research (18.4): 331–33.

- ↑ Svetlana Kaliadina et al., "The Family of W.W. Leontief in Russia", Economic Systems Research, vol.18 (2006), 335–45 (http://econpapers.repec.org/article/tafecsysr/default18.htm).

- ↑ Estelle Leontief, Genia & Wassily. A Russian American Memoir, Zephyr Press: Somerville Mass., 1987

- ↑ Svetlana Kaliadina et al., "W.W. Leontief and the Repressions of the 1920s: an Interview", Economic Systems Research, vol.18 (2006), 347–355 (http://econpapers.repec.org/article/tafecsysr/default18.htm).

- ↑ Lay, David C. (2003). Linear Algebra and Its Applications (Third ed.). Addison Wesley. p. 1. ISBN 0-201-70970-8.

- ↑ Polenske, Karen R. (2004). "Leontief's ‘magnificent machine’ and other contributions to applied economics". Wassily Leontief and Input-Output Economics. Cambridge University Press. p. 12.

- ↑ See also, Leontief, Input-Output Economics (Scientific American, 1951) reprinted in Input-Output Economics (1966).

- ↑ http://science.slashdot.org/story/10/02/17/2317239/PageRank-Type-Algorithm-From-the-1940s-Discovered?art_pos=3

- ↑ http://www.technologyreview.com/blog/arxiv/24821/

- ↑ Massimo Franceschet (2010). "PageRank: Standing on the shoulders of giants". arXiv:1002.2858

[cs.IR].

[cs.IR]. - 1 2 "Wassily Leontief (1906–1999)". Econlib. Library of Economics and Liberty. 5 May 2014. Retrieved 5 May 2014.

- ↑ Leontief, W., Theoretical Assumptions and nonobserved Facts, American Economic Review, Vol. 61, No. 1 (March 1971), pp. 1-7; Presidential address to the American Economic Association 1970.

- ↑ Hallak, Jacques; Caillods, Françoise (1995). "Educational Planning: The International Dimension". ISBN 9780815320241.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Wassily Leontief |

- Autobiography

- Information from www.iioa.org

- Article by James K. Galbraith

- Interview with W.Leontief by S.A.Kalyadina (in Russian)

- IDEAS/RePEc

- Appearances on C-SPAN