Warren Hastings

| His Excellency The Right Honourable Warren Hastings | |

|---|---|

| |

| Governor of the Presidency of Fort William (Bengal) | |

|

In office 28 April 1772 – 20 October 1774 | |

| Preceded by | John Cartier |

| Succeeded by | Position Abolished |

| Governor-General of the Presidency of Fort William | |

|

In office 20 October 1774 – 8 February 1785[1] | |

| Monarch | George III |

| Preceded by | Position Created |

| Succeeded by |

Sir John Macpherson, Bt As Acting Governor-General |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

6 December 1732 Churchill, Oxfordshire |

| Died |

22 August 1818 (aged 85) Daylesford, Gloucestershire |

| Nationality | British |

| Alma mater | Westminster School |

Warren Hastings (6 December 1732 – 22 August 1818), an English statesman, was the first Governor of the Presidency of Fort William (Bengal), the head of the Supreme Council of Bengal, and thereby the first de facto Governor-General of India from 1772 to 1785. He was accused of corruption and impeached in 1787, but after a long trial he was acquitted in 1795. He was made a Privy Counsellor in 1814.

Early life

Hastings was born in Churchill, Oxfordshire in 1732 to a poor father, Penystone Hastings, and a mother, Hester Hastings, who died soon after he was born.[2] He attended Westminster School where he was a contemporary of the future Prime Ministers Lord Shelburne and the Duke of Portland as well as the poet William Cowper.[3] He joined the British East India Company in 1750 as a clerk and sailed out to India reaching Calcutta in August 1750.[4] Hastings built up a reputation for hard work and diligence, and spent his free time learning about India and mastering Urdu and Persian.[5] He was rewarded for his work in 1752 when he was promoted and sent to Kasimbazar, an important British trading post in Bengal where he worked for William Watts. While there he received further lessons about the nature of East Indian politics.

At the time, British traders still operated at the whim of local rulers, and so Hastings and his colleagues were unsettled by the political turmoil of Bengal, where the elderly moderate Nawab Alivardi Khan was likely to be succeeded by his grandson Siraj ud-Daulah, although several other rival claimants were eyeing the throne. This made British trading posts throughout Bengal increasingly insecure, as Siraj ud-Daulah was known to harbour anti-European views and be likely to launch an attack once he took power. When Alivardi Khan died in April 1756, the British traders and small garrison at Kasimbazar were left vulnerable. On 3 June, after being surrounded by a much larger force, the British were persuaded to surrender to prevent a massacre taking place.[6] Hastings was imprisoned with others in the Bengali capital, Murshidabad, while the Nawab's forces marched on Calcutta and captured it. The garrison and civilians were then locked up under appalling conditions in the Black Hole of Calcutta.

For a while Hastings remained in Murshidabad and was even used by the Nawab as an intermediary, but fearing for his life, he escaped to the island of Fulta, where a number of refugees from Calcutta had taken shelter. While there, he met and married Mary Buchanan, the widow of one of the victims of the Black Hole. Shortly afterwards a British expedition from Madras under Robert Clive arrived to rescue them. Hastings served as a volunteer in Clive's forces as they retook Calcutta in January 1757. After this swift defeat, the Nawab urgently sought peace and the war came to an end. Clive was impressed with Hastings when he met him, and arranged for his return to Kasimbazar to resume his pre-war activities. Later in 1757 fighting resumed, leading to the Battle of Plassey, where Clive won a decisive victory over the Nawab. Siraj ud-Daulah was overthrown and replaced by his uncle Mir Jafar, who initiated pro-British policies.

Rising status

In 1758 Hastings became the British Resident in the Bengali capital of Murshidabad – a major step forward in his career – at the instigation of Clive. His role in the city was ostensibly that of an ambassador but as Bengal came increasingly under the dominance of the East India Company he was often given the task of issuing orders to the new Nawab on behalf of Clive and the Calcutta authorities.[7] Hastings personally sympathised with Mir Jafar and regarded many of the demands placed on him by the Company as excessive. Hastings had already developed a philosophy that was grounded in trying to establish a more understanding relationship with India's inhabitants and their rulers, and he often tried to mediate between the two sides.

During Mir Jafar's reign the East India Company exerted an increasingly large role in the running of the region, and effectively took over the defence of Bengal against external invaders when Bengal's troops proved insufficient for the task. As he grew older, Mir Jafar became gradually less effective in ruling the state, and in 1760 British troops ousted him from power and replaced him with Mir Qasim.[8] Hastings expressed his doubts to Calcutta over the move, believing they were honour-bound to support Mir Jafar, but his opinions were overruled. Hastings established a good relationship with the new Nawab and again had misgivings about the demands he relayed from his superiors. In 1761 he was recalled and appointed to the Calcutta council.

Conquest of Bengal

Hastings was personally angered when he conducted an investigation into trading abuses in Bengal. He alleged some European and British-allied Indian merchants were taking advantage of the situation to enrich themselves personally. Persons travelling under the unauthorised protection of the British flag engaged in widespread fraud and in illegal trading, knowing that local customs officials would thereby be cowed into not interfering with them. Hastings felt this was bringing shame on Britain's reputation, and he urged the ruling authorities in Calcutta to put an end to it. The Council considered his report but ultimately rejected Hastings' proposals and he was fiercely criticised by other members, many of whom had themselves profited from the trade.[9]

Ultimately, little was done to stem the abuses, and Hastings began to consider quitting his post and returning to Britain. His resignation was only delayed by the outbreak of fresh fighting in Bengal. Once on the throne Qasim proved increasingly independent in his actions, and he rebuilt Bengal's army by hiring European instructors and mercenaries who greatly improved the standard of his forces.[10] He felt gradually more confident and in 1764 when a dispute broke out in the settlement of Patna he captured its British garrison and threatened to execute them if the East India Company responded militarily. When Calcutta dispatched troops anyway, Mir Qasim executed the hostages. British forces then went on the attack and won a series of battles culminating in the decisive Battle of Buxar in October 1764. After this Mir Qasim fled into exile in Delhi, where he later died (1777). The Treaty of Allahabad (1765) gave the East India Company the right to collect taxes in Bengal on behalf of the Mughal Emperor.

Hastings resigned in December 1764 and sailed for Britain the following month. He left deeply saddened by the failure of the more moderate strategy that he had supported, but which had been rejected by the hawkish members of the Calcutta Council. Once he arrived in London Hastings began spending far beyond his means. He stayed in fashionable addresses and had his picture painted by Joshua Reynolds in spite of the fact that, unlike many of his contemporaries, he had not amassed a fortune while in India. Eventually, having run up enormous debts, Hastings realised he needed to return to India to restore his finances, and applied to the East India Company for employment. His application was initially rejected as he had made many political enemies, including the powerful director Laurence Sulivan. Eventually an appeal to Sulivan's rival Robert Clive secured Hastings the position of deputy ruler at the city of Madras. He sailed from Dover in March 1769. On the voyage he met the German Baroness Imhoff and her husband. He soon fell in love with the Baroness and they began an affair, seemingly with her husband's consent. Hastings' first wife, Mary, had died in 1759, and he planned to marry the Baroness once she had obtained a divorce from her husband. The process took a long time and it was not until 1777 when news of divorce came from Germany that Hastings was finally able to marry her.

Madras and Calcutta

Hastings arrived in Madras shortly after the end of the First Anglo-Mysore War of 1767–1769, during which the forces of Hyder Ali had threatened the capture of the city. The Treaty of Madras (29 March 1769) which ended the war failed to settle the dispute and three further Anglo-Mysore Wars followed (1780-1799). During his time at Madras Hastings initiated reforms of trading practices which cut out the use of middlemen and benefited both the Company and the Indian labourers, but otherwise the period was relatively uneventful for him.[11]

By this stage Hastings shared Clive's view that the three major British Presidencies (settlements) – Madras, Bombay and Calcutta – should all be brought under a single rule rather than being governed separately as they currently were.[11] In 1771 he was appointed to be Governor of Calcutta, the most important of the Presidencies. In Britain moves were underway to reform the divided system of government and to establish a single rule across all of British India with its capital in Calcutta. Hastings was considered the natural choice to be the first Governor General.

While Governor, Hastings launched a major crackdown on bandits operating in Bengal, which proved largely successful.

He also faced the severe Bengal Famine, which resulted in about ten million deaths.

Governor-General

In 1774,[12] he was appointed the first Governor-General of Bengal. He was also the first governor of India.[13]:190 The post was new, and British mechanisms to administer the territory were not fully developed. Regardless of his title, Hastings was only a member of a five-man Supreme Council of Bengal[13]:190 so confusedly structured that it was difficult to tell what constitutional position Hastings actually held.[14]

Bhutan and Tibet

In 1773, Hastings responded to an appeal for help from the Raja of the princely state of Cooch Behar to the north of Bengal, whose territory had been invaded by Zhidar, the Druk Desi of Bhutan the previous year. Hastings agreed to help on the condition that Cooch Behar recognise British sovereignty.[15] The Raja agreed and with the help of British troops they pushed the Bhutanese out of the Duars and into the foothills in 1773.

The Druk Desi, returned to face civil war at home. His opponent Jigme Senge, the regent for the seven-year-old Shabdrung (the Bhutanese equivalent of the Dalai Lama), had supported popular discontent. Zhidar was unpopular for his corvee tax (he sought to rebuild a major dzong in one year, an unreasonable goal), as well as for his overtures to the Manchu Emperors which threatened Bhutanese independence. Zhidar was soon overthrown and forced to flee to Tibet, where he was imprisoned and a new Druk Desi, Kunga Rinchen, installed in his place. Meanwhile, the Sixth Panchen Lama, who had imprisoned Zhidar, interceded on behalf of the Bhutanese with a letter to Hastings, imploring him to cease hostilities in return for friendship. Hastings saw the opportunity to establish relations with both the Tibetans and the Bhutanese and wrote a letter to the Panchen Lama proposing "a general treaty of amity and commerce between Tibet and Bengal."[16]

In February 1782, news having reached the headquarters of the EIC in Calcutta of the reincarnation of the Panchen Lama, Hastings proposed despatching a mission to Tibet with a message of congratulation designed to strengthen the amicable relations established by Bogle during his earlier visit. With the assent of the EIC Court of Directors, Samuel Turner was appointed chief of the Tibet mission on 9 January 1783 with fellow EIC employee and amateur artist Samuel Davis as "Draftsman & Surveyor".[17] Turner returned to the Governor-General's camp at Patna in 1784 where he reported that although unable to visit the Tibetan capital at Lhasa, he had received a promise that merchants sent to the country from India would be encouraged.[18]

Turner was also instructed to obtain a pair of yaks on his travels, which he duly did. They were transported to Hasting's menagerie in Calcutta and on the Governor-General's return to England, the yaks went too, although only the male survived the difficult sea voyage. Noted artist George Stubbs subsequently painted the animal's portrait as The Yak of Tartary and in 1854 it went on to appear, albeit stuffed, at The Great Exhibition at Crystal Palace in London.[19]

Hasting's return to England ended any further efforts to engage in diplomacy with Tibet.

Resignation and impeachment

In 1784, after ten years of service, during which he helped extend and regularise the nascent Raj created by Clive of India, Hastings resigned.

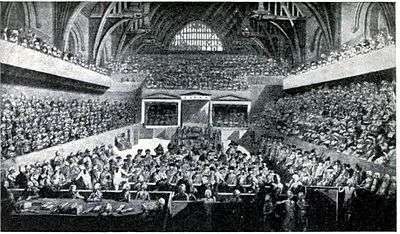

Upon his return to England he was impeached in the House of Commons for crimes and misdemeanors during his time in India, especially for the alleged judicial killing of Maharaja Nandakumar. At first deemed unlikely to succeed,[20] the prosecution was managed by MPs including Edmund Burke, who was encouraged by Sir Philip Francis, whom Hastings had wounded during a duel in India,[13]:190 Charles James Fox and Richard Brinsley Sheridan. When the charges of his indictment were read, the twenty counts took Edmund Burke two full days to read.[21]

The house sat for a total of 148 days over a period of seven years during the investigation.[22] The investigation was pursued at great cost to Hastings personally, and he complained constantly that the cost of defending himself from the prosecution was bankrupting him. He is rumoured to have once stated that the punishment given him would have been less extreme had he pleaded guilty.[23] The House of Lords finally made its decision on 24 April 1795, acquitting him on all charges.[24] The Company subsequently compensated him with 4,000 Pounds Sterling annually.

Throughout the long years of the trial, Hastings lived in considerable style at his town house, Somerset House, Park Lane.[25] Among the many who supported him in print was the pamphleteer and versifier Ralph Broome.[26] Others disturbed by the perceived injustice of the proceedings included Fanny Burney.[27]

The letters and journals of Jane Austen and her family, who knew Hastings, show that they followed the trial closely.

Later life

His supporters from the Edinburgh East India Club, as well as a number of other gentlemen from India, gave a reportedly "elegant entertainment" for Hastings when he visited Edinburgh. A toast on the occasion went to the "Prosperity to our settlements in India" and wished that "the virtue and talents which preserved them be ever remembered with gratitude."[28]

In 1788 he acquired the estate at Daylesford, Gloucestershire, including the site of the medieval seat of the Hastings family. In the following years, he remodelled the mansion to the designs of Samuel Pepys Cockerell, with classical and Indian decoration, and gardens landscaped by John Davenport. He also rebuilt the Norman church in 1816, where he was buried two years later.

In 1801 he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society.[29]

Hastings's administrative ethos and legacy

During the final quarter of the 18th century, many of the Company's senior administrators realised that, in order to govern Indian society, it was essential that they learn its various religious, social, and legal customs and precedents. The importance of such knowledge to the colonial government was clearly in Hastings's mind when, in 1784, he remarked:

Every application of knowledge and especially such as is obtained in social communication with people, over whom we exercise dominion, founded on the right of conquest, is useful to the state ... It attracts and conciliates distant affections, it lessens the weight of the chain by which the natives are held in subjection and it imprints on the hearts of our countrymen the sense of obligation and benevolence... Every instance which brings their real character will impress us with more generous sense of feeling for their natural rights, and teach us to estimate them by the measure of our own... But such instances can only be gained in their writings; and these will survive when British domination in India shall have long ceased to exist, and when the sources which once yielded of wealth and power are lost to remembrance[30]

Under Hastings's term as governor-general, a great deal of administrative precedent was set which profoundly shaped later attitudes towards the government of British India. Hastings had a great respect for the ancient scripture of Hinduism and set the British position on governance as one of looking back to the earliest precedents possible. This allowed Brahmin advisors to mould the law, because no English person thoroughly understood Sanskrit until Sir William Jones, and, even then, a literal translation was of little use; it needed to be elucidated by religious commentators who were well-versed in the lore and application. This approach accentuated the Hindu caste system and to an extent the frameworks of other religions, which had, at least in recent centuries, been somewhat more flexibly applied. Thus, British influence on the fluid social structure of India can in large part be characterised as a solidification of the privileges of the Hindu caste system through the influence of the exclusively high-caste scholars by whom the British were advised in the formation of their laws.

In 1781, Hastings founded Madrasa 'Aliya; in 2007, it was transformed into Aliah University by the Government of India, at Calcutta. In 1784, Hastings supported the foundation of the Bengal Asiatic Society, now the Asiatic Society of Bengal, by the oriental scholar Sir William Jones; it became a storehouse for information and data on the subcontinent and has existed in various institutional guises up to the present day.[31] Hastings' legacy has been somewhat dualistic as an Indian administrator: he undoubtedly was able to institute reforms during the time he spent as governor there that would change the path that India would follow over the next several years. He did, however, retain the strange distinction of being both the "architect of British India and the one ruler of British India to whom the creation of such an entity was anathema."[32]

Legacy

The city of Hastings, New Zealand and the Melbourne outer suburb of Hastings, Victoria, Australia were both named after him.

"Hastings" is the name of one of the 4 School Houses in La Martiniere for Boys, Calcutta and La Martiniere for Girls Kolkata. It is represented by the colour red.

"Hastings" is also the name of one of the 4 School Houses in Bishop Westcott Boys' School, Ranchi. It is also represented by the colour red.

"Hastings" is a Senior Wing House at St Paul's School, Darjeeling, India, where all the senior wing houses are named after Anglo-Indian colonial figures.

There is also a road in Kolkata, India, named after him.

Literature

Warren Hastings took keen interest in translating the Bhagavad Gita into English, and as a result of his efforts the first English translation appeared in 1785. Warren Hastings wrote the introduction to the English translation of the Bhagavad Gita, dated 4 October 1784, from Benares.[33]

"Warren Hastings and His Bull" is a short story written by Indian writer Uday Prakash. It was adapted for stage under the same name by the director Arvind Gaur. It is a socio-economic political satire that presents Warren Hastings's interaction with traditional India.

See also

References

- ↑ Bengal Public Consultations February 12, 1785. No. 2. Letter from Warren Hastings, 8th February, formally declaring his resignation of the office of Governor General.

- ↑ Lyall, Sir Alfred (1920). Warren Hastings. London: Macmillan and Co. p. 1.

- ↑ Turnbull, Patrick. Warren Hastings. New English Library, 1975. p.17.

- ↑ Turnbull pp. 17–18

- ↑ Turnbull pp. 19–21

- ↑ Turnbull p. 23

- ↑ Turnbull pp. 27–28

- ↑ Turnbull pp. 34–35

- ↑ Turnbull pp. 36–40

- ↑ Turnbull p. 36.

- 1 2 Turnbull p. 52.

- ↑ Europe, 1450 to 1789: Encyclopedia of the Early Modern World | 2004 | SCHWEIZER, KARL W. COPYRIGHT 2004 The Gale Group Inc.

- 1 2 3 Wolpert SA. A New History of India. 1982. ISBN 9780195029499

- ↑ The Earl of Birkenhead, Famous Trials of History (Garden City: Garden City Publishing Company, 1926) p. 165

- ↑ Minahan, James B. (2002). Encyclopedia of the Stateless Nations: Ethnic and National Groups Around the World A-Z. ABC-CLIO. p. 1556. ISBN 978-0-313-07696-1.

- ↑ Younghusband 1910, pp. 5–7.

- ↑ Davis, Samuel; Aris, Michael (1982). Views of Medieval Bhutan: the diary and drawings of Samuel Davis, 1783. Serindia. p. 31.

- ↑ Younghusband 1910, p. 27.

- ↑ Harris, Clare (2012). The Museum on the Roof of the World: Art, Politics, and the Representation of Tibet. University of Chicago Press. pp. 30–33. ISBN 978-0-226-31747-2.

- ↑ Macaulay, Thomas Babington. "Warren Hastings (1841), an essay by Thomas Babington Macaulay." Columbia University in the City of New York. (accessed 20 May 2009).

- ↑ The Earl of Birkenhead, Famous Trials of History (Garden City: Garden City Publishing Company, 1926) 170

- ↑ Sir Alfred Lyall, Warren Hastings (London: Macmillan and Co, 1920) 218

- ↑ The Earl of Birkenhead, Famous Trials of History (Garden City: Garden City Publishing Company, 1926) 173

- ↑ Political Trials in History by Ron Christenson, p. 178-179, ISBN 0-88738-406-4

- ↑ 'Park Lane', in Survey of London: volume 40: The Grosvenor Estate in Mayfair, Part 2 (The Buildings) (1980), pp. 264–289, accessed 15 November 2010

- ↑ In: Letters of Simkin the Second to his dear brother in Wales, containing a humble description of the trial of Warren Hastings, Esq. (1788) Letters of Simpkin the Second, Poetic Recorder, of all the proceedings upon the Trial of Warren Hastings (1789), and An Elucidation of the Articles of Impeachment preferred by the last Parliament against Warren Hastings, Esq., later Governor of Bengal (1790).

- ↑ The Journals and Letters of Fanny Burney (Madame d'Arblay) I. 1791–1792, p. 115 ff.

- ↑ Gilbert, W.M., editor, Edinburgh in the Nineteenth Century, Edinburgh, 1901: 44

- ↑ "Fellows details". Royal Society. Retrieved 23 January 2017.

- ↑ Cohn, Bernard S (1997). "Colonialism and its forms of knowledge: The British in India". Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Keay, John (2000). India: A History. United States: Grove Press, Publishers Group West. p. 426. ISBN 0-8021-3797-0.

- ↑ ———— (1991). "The Honourable Company". New York: Macmillan: 394.

- ↑ Garrett, John; Wilhelm, Humboldt, eds. (1849). The Bhagavat-Geeta, Or, Dialogues of Krishna and Arjoon in Eighteen Lectures (PDF). Bangalore: Wesleyan Mission Press. Retrieved 18 January 2017.

Bibliography

- Davies, Alfred Mervyn. Strange destiny: a biography of Warren Hastings (1935)

- Ghosh, Suresh Chandra. The Social Condition of the British Community in Bengal: 1757–1800 (Brill, 1970)

- Feiling, Keith, Warren Hastings (1954)

- Lawson, Philip. The East India Company: A History (Routledge, 2014)

- Marshall, P.J., The impeachment of Warren Hastings (1965)

- Marshall, P. J. "Hastings, Warren (1732–1818)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford University Press, 2004); online edn, Oct 2008 accessed 11 Nov 2014

- Moon, Penderel. Warren Hastings and British India (Macmillan, 1949)

- Turnbull, Patrick. Warren Hastings. (New English Library, 1975)

- Younghusband, Francis (1910). India and Tibet: a history of the relations which have subsisted between the two countries from the time of Warren Hastings to 1910; with a particular account of the mission to Lhasa of 1904. London: John Murray.

Primary sources

- Forrest, G.W., ed. Selections from the State Papers of the Governors-General of India: Warren Hastings (2 vols.), Blackwell's, Oxford (1910)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Warren Hastings. |

- Warren Hastings at Project Gutenberg (within Critical and Historical Essays (Macaulay))

Warren Hastings public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Warren Hastings public domain audiobook at LibriVox- House of Warren Hastings in Calcutta

| Government offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| New creation | Governor-General of India 1773–1785 |

Succeeded by Sir John Macpherson, acting |