Warnaco Group

| |

| Public | |

| Traded as | NYSE: WRC |

| Industry | Textiles, clothing and luxury goods |

| Fate | acquired by PVH in 2013 |

| Founded |

501 Seventh Avenue New York City, New York, United States.[1] (1874)[2] |

| Founder | Ira De Ver Warner, Lucien C. Warner |

| Defunct | 2013 |

| Headquarters |

501 Seventh Ave, New York City, New York, United States, 10018 |

Area served | Worldwide |

Key people |

|

| Revenue | US$ 2.51 billion(FY 2011)[5] |

| US$181.5 million (FY 2011)[5] | |

| US$127.5 million (FY 2011)[5] | |

Number of employees | 7,136 (YE 2011) [5] |

| Parent | Phillips-Van Heusen |

| Divisions |

Sportswear Group:

Intimate Apparel Group:

Swimwear Group:

Distribution:

|

| Website | pvh.com |

The Warnaco Group, Inc. was an American textile/clothing corporation which designed, sourced, marketed, licensed, and distributed a wide range of underwear, sportswear, and swimwear worldwide. Its products were sold under several brand names including Calvin Klein, Speedo, Chaps, Warner's, and Olga. On 31 October 2012, the company announced that it would be acquired by PVH for $2.8 billion in cash and stock. [6] The deal that will give the PVH more control of the Calvin Klein clothing brand as it will unite Calvin Klein formal, underwear, jeans and sportswear lines. It was acquired by PVH in Feb 2013.[7]

History

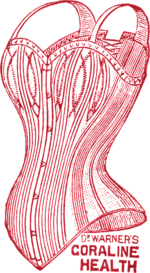

Dr. Warner's Health Corsets

In the late 19th century, Dr. Lucien Warner, a prominent physician gave up his Cortlandville, NY practice to begin a new career on the medical lecturing circuit, specializing in women’s health issues. Dr. Warner lectured about the harmful effects of the rigid steel-boned corsets of the time. After seeing how little influence his lectures had on women’s attitudes towards fashion, he returned to his New York home and began a more aggressive approach to fighting the ills caused by the corset.[8] In 1873, he designed a corset that provided both the shape desired by women and the flexibility required to allow some movement and reduce injuries caused by previous designs. The next year, Lucien Warner and his brother Dr. Ira De Ver Warner gave up their medical practices and founded Warner Brothers Corset Manufacturers.[9]

Dr. Warner’s Coraline Health Corsets, as they were marketed,[10] were made up of two pieces of cloth which were laced or clasped together. These revolutionary undergarments also featured shoulder straps and more flexible boning and lateral bust supports[11] made of Coraline, a product of the fibers of the Mexican Ixtle plant.[12][13] By 1876, the popularity of this new, more flexible design had grown in popularity so much so that the company moved its manufacturing operations to Bridgeport, CT, where approximately 1,200 people were employed to produce approximately 6,000 corsets daily.[14] In 1883 Harper’s Bazaar advertised the four most popular corsets in America as Dr. Warner’s models[15] The brothers claimed patents and trademarks on "health corset" and they had international manufacturing.[16] The success of the Warners’ designs had made the brothers millionaires and in 1894 they retired and turned control of the company over to De Ver’s son, D.H. and the Warner Brothers partnership was changed to a corporation.

The Warner Brothers Corset Co.

The turn of the century saw even greater success for the company in the hands of the founders’ sons. New products included the rust-proof corset and combination corset and hose-supporter. By 1913 sales reached $7 million and profits averaged $700,000 annually[17] Two years later, The Warner Brothers Corset Co. paid $1,500 for Mary Phelps Jacob’s patent for the brassiere - a move which helped boost revenues to $12.6 million by 1920.[17]

The Jazz Age and Flapper movement of the 1920s saw the desire for less restrictive fashions. Women had a more care-free attitude toward life and ditched the corset and pantaloons in favor of breast-binding bandeaus and step-in panties.[18] This was a difficult time for the company. Sales through the decade declined and efforts made by the company to adapt to these changing times were met with little success.

Depression Era

The Great Depression of the 1930s was difficult on the clothing industry and Warner was no exception to this financial suffering. Even as the boyish figure of the previous decade’s Flappers fell out of style and curves made a return to fashion, Warner struggled. By 1932, the company had lost more than $1 million.[17] The company's troubles were only made worse by the personal deterioration of CEO, D. H. Warner, who was known as a depraved womanizer.[17] After his wife died in 1931, D.H. continued to finance his debauchery with company profits and drink to excess before dying in 1934 at the age of 66. Control of the company was handed to his son-in-law, John Field.[17]

ABC and IPO

With the corset all but extinct by the mid-1930s, the company’s new leadership focused on developing new products. In 1937, the company that revolutionized corsetry revolutionized the brassiere by assigning letters to various cup sizes.[19] The ABC Alphabet Bra set the standard for bra sizing that is still used today. By the early 1940s, the company was profitable again, bringing in $1 million by 1947.[17] Sales of bras, girdles, and the cross-promotion of the Merry Widow line of corselets with the 1952 Lana Turner movie of the same name, led to record profits.[17]

A partnership between DuPont and Warners lead to the 1959 invention of Lycra, which allowed for new designs in shapewear and more snug-fitting bras.[20] The late 1950s also saw Warner Brothers diversify its product lineup to include menswear and accessories, as well as sportswear for both men and women. Distribution was expanded by sales in large chain department stores such as JC Penney and Sears. The company also expanded production, opening manufacturing facilities in South America and Europe. In 1960, Warner Brothers Company purchased major American shirt manufacturer C.F. Hathaway strengthening the company’s foothold in the sportswear market. Warner Brothers went public in 1961 and was soon generating revenues in excess of $100 million.[17] In 1966, it acquired another large clothing maker, the White Stag Manufacturing Company.[21]

Warnaco

The Warner Brothers Company changed its name to Warnaco, Inc. in 1968, and continued to grow its business exponentially through various mergers and acquisitions throughout the 1970s. By the middle of the decade, Warnaco had become a multi-national clothing conglomerate with almost 20 divisions. Despite the company’s diverse portfolio, however, Warnaco was struggling to turn a profit. Recognizing the potential failure, Field handed management of the company over to James Walker and Philip Lamoureux. Walker was named CEO in 1977.[22][23]

Lamoureux and Walker turned the company around quickly and in 1982, Lamoureux left the company. A year later, Walker died unexpectedly.[17] That year brought in $28.3 million.[17] However, some of the cost-cutting measures implemented by Lamoureux and Walker — including cutbacks in research and in advertising — hurt the company more than helping it. In 1986, after being away from the company for nine years,[24] former lingerie division president Linda J. Wachner engineered a $550 million hostile takeover[25] Wachner had previously risen through the ranks at Max Factor, making the declining cosmetics company profitable again within just two years.[24] She wasted no time at Warnaco and right away went to work streamlining the company’s fifteen divisions into just two categories: menswear and underwear.

The Wachner years

In 1990, Wachner formed a new corporation, Authentic Fitness Corp., for the purpose of separating Warnaco’s activewear lines including Speedo and White Stag ski clothing. Wachner’s intention was to transform Speedo from swimwear label to retail concept.[26] Authentic fitness went public in June 1992 and opened its first Speedo Authentic retail store five months later[26] In 1993, Authentic Fitness had a licensing deal with Oscar de la Renta, Ltd. and had acquired swimwear labels Cole, Catalina, and Anne Cole — each from bankruptcies. That same year, Wachner secured a sponsorship deal for the 1996 Summer Olympics in Atlanta, GA.[26]

By 1991, Warnaco’s lingerie division had license agreements with Valentino, Ungaro, Scaasi, Bob Mackie, Victoria’s Secret and Fruit of the Loom. The menswear division produced shirts, sweaters, neckties and other accessories under names including Christian Dior, Hathaway, Chaps by Ralph Lauren, and Jack Nicklaus. At the end of 1991, the company produced $195.4 million in gross profits and Linda Wachner was named Business Woman of the Year by Fortune Magazine.[27]

The remainder of the decade saw Wachner take her company on a buying spree, acquiring designer labels Calvin Klein Underwear, Body Slimmers (purchased from Nancy Ganz, wife of Mitchell S. Steir), ABS by Allan Schwartz, as well as private label sleepwear manufacturers GJM Group, French lingerie company Lejaby-Euralis.[28] Warnaco also acquired the license for Calvin Klein Jeans and Calvin Klein retail stores through its takeover of Designer Holdings, Inc.[29] The license for Calvin Klein children’s clothing was purchased from Commerce Clothing[30] Warnaco closed out the 1990s by selling off its underperforming Hathaway label and reacquiring Authentic Fitness.

The company’s success peaked in 1998 with $1.95 billion in revenue.[17] Soon after, however, sales dropped rapidly and — saddled with debt from all the recent acquisitions and mergers — in 2000, the company lost $200 million.[31] In 2001, Warnaco filed for Chapter 11 protection and Wachner was fired.

A new beginning

On 4 February 2003, Warnaco emerged from bankruptcy. As part of its restructuring, the company sold its White Stag trademark to Wal-Mart and later decided to exit the designer swimwear market and focus on strengthening its Speedo products. The company sold off Ocean Pacific to Iconix Brand Group after just three years of ownership.[32] Also sold, were Catalina, Anne Cole and Cole of California brands. This netted the company approximately $25 million.[33] In 2008, the company also ceased operations under the Michael Kors and Nautica labels, citing a collective $1.7 million in losses from the two brands.[33] In further efforts to boost its swimwear line, Speedo renewed its contract with 8-time Olympic gold medalist Michael Phelps, extending his endorsement through the next Summer Games.[34] Warnaco provides private label swimsuits for Victoria’s Secret.[33][35] In order to strengthen its "core intimates" group, (Warner's, Olga, Calvin Klein Underwear), the company shed private label GJM[36] and high-end lingerie brand Lejaby.[37]

Since emerging from bankruptcy, Warnaco Group’s annual income Reports have shown steady growth.[38] Calvin Klein continues to be a strong performer for the company in both the jeans and intimates sectors. As of 2 January 2010, the company operated over 1,000 Calvin Klein retail stores worldwide as well as three online stores.[33][39] It also licenses or franchises an additional 624 stores and the Calvin Klein brand accounted for 75% of the Warnaco Group's $2 billion net sales in 2009.[39] At the end of 2010's second quarter (ending 3 July), Warnaco reported that all three divisions — Intimates, Swimwear and Sportswear — contributed to its 14% growth in net revenues to $519.3 million[40] and industry analysts expect continued growth.[39][40][41][42][43] In August 2010 The Motley Fool named Warnaco one of its Top 10 Values in Consumer Durables, citing the stock's low price-to-earnings multiples as well as its low risk and its potential for growth.[44]

Controversies and criticisms

Bridgeport Strike of 1915

During the summer of 1915, approximately 1,300 women and girls employed by The Warner Brothers Corset Company factory in Bridgeport, CT, walked off the job.[45] The strike, which was one of 179 strikes recorded that year,[46] was in favor of eight-hour work days[45] and a 20% increase in wages.[47] On 18 August that year, the nearly 4,000 striking workers — who were organized as part of the International Textile Workers of America union- accepted the management’s offer of a 12.5% raise and eight-hour days.[48]

Only one worker was reported injured during this strike. Connecticut newspaper The Day reported “a Miss Jones...who is believed to have objected to the [negotiation] proceedings, is said to have been roughly handled by the other strikers, and to have had her clothing almost torn from her.” No one was arrested for this attack.[45]

Made in the U.S.A.

Early in 1999, Warnaco was one of 18 companies initially named in three class-action lawsuits filed under US Federal RICO statutes. The lawsuits were filed by several labor and human rights groups on behalf of more than 50,000 workers from China, the Philippines, Bangladesh and Thailand.[49][50] Ultimately 26 U.S. companies and 23 Saipan garment factories would be named as defendants.[50]

The suits claimed that the garment factories — located in Saipan, Northern Mariana Islands, a United States Commonwealth — regularly employed immigrant laborers who were duped into paying a "recruiting fee" of up to $7,000[50] so they can work in The United States. Upon arrival in Saipan, the workers are forced to surrender their passports and work off the money they owe, in effect making them indentured servants. These factories produce clothing for the companies named in the suit. The workers further claimed that they were forced to sign "shadow contracts" waiving basic human rights, including the freedom to date or marry. And they emphasize the poor working and living conditions for workers. The suits allege they work and live in crowded, unsanitary factories and shanty-like housing compounds that are in flagrant violation of federal law.[49]

Almost immediately, Warnaco denied any wrongdoing, stating that they hire subcontractors that strictly follow U.S. law[51] and in the spring of 1999, was among the first companies to settle.[52] By 2004 all remaining companies – with the exception of Levi Strauss whose case was ultimately dismissed – had settled without admitting to any wrongdoing. The Saipan garment workers had won a collective $20 million as well as better oversight and improved working conditions.[53]

SEC investigation

On 11 May 2004, the Securities and Exchange Commission announced a settlement in its three-year-long investigation of Warnaco and its auditing firm, PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP (PwC). The investigation stemmed from an overstatement of $145 million worth of inventory on Warnaco’s 1998 Form 10-K.[54] The SEC alleged that Warnaco knew about this overstatement when they released a press statement lauding the company’s “record results” for its fourth quarter and fiscal year ending 1998. This overstatement would force Warnaco to restate its earnings for the three prior years. The commission complained Warnaco “falsely portrayed the inventory write-down as a part of the company's write-off of deferred start-up costs under a new accounting pronouncement.[55]”

The complaints filed by the SEC claim PwC’s role in this alleged cover-up was that they caught the error during an audit but they “failed to object” to Warnaco’s "mischaracterization" of this error and that PwC incorporated this mischaracterization into their own audit report.[56]

In the suit, the SEC specifically names William Finklestein, who was Vice President and CFO at the time of the allegation, claiming “As CFO, Finkelstein directed the offsetting of cash against debt. He also reviewed and signed the quarterly report.[33]” Linda Wachner was also named in the suit as she was President and CEO at the time. In the its press release announcing the settlement of the suit, the commission stated “at the time she approved and signed the 1998 annual report, Wachner knew or should have known that the restatement of the company's financial results was caused by material flaws in the cost accounting and internal control systems at one of the company's largest divisions and was not related to the write-up of deferred start-up or start-up related costs." The commission also found that "Wachner knew or should have known that the division's inventory costing control system was inadequate to ensure the accuracy of Warnaco's books and records and failed to ensure that proper internal controls were in place.[55]” Stanley P. Silverstein, who was Warnaco’s general counsel at the time was also named, as he, too, signed off on the report.

PricewaterhouseCoopers settled with the SEC and agreed to pay a $2.4 million penalty. Wachner was found to have caused the oversight and was ordered to pay $1.3 million in disgorgement. Finkelstein was ordered to pay $189,464 in disgorgement as well as a civil penalty of $75,000. He was barred for four years from serving as an officer or director of a public company. Silverstein was censured and ordered to pay $165,772.[33]

Calvin Klein, et al. vs. The Warnaco Group, et al.

On 30 May 2000, Calvin Klein, Inc. filed suit against Warnaco Group, Inc. and its CEO, Linda Wachner. The suit alleged that Warnaco had diluted the Calvin Klein brand name by producing merchandise that was not authorized or approved by Calvin Klein and that Warnaco was distributing Calvin Klein jeanswear through unapproved discount outlets, such as warehouse clubs, like Costco and BJ’s. Klein, himself appeared on CNN’s Larry King Live shortly after the suit was filed and stated these practices have been taking place since Warnaco acquired the license three years prior. Calvin Klein had sought to regain control of its jeanswear license. Warnaco’s initial response to the suit, which King read on the air, called the complaint “without merit.” The statement further accused Calvin Klein of “throwing stones at Warnaco,” in a “desperate attempt... to cover up and distract focus from the highly deteriorated business state of CKI".[57] In response to Klein's television appearance, Warnaco filed a countersuit accusing Klein of trademark libel for not only maligning Warnaco but also Calvin Klein's own products.[58] The suit was settled in 2001 and sealed with a "fashionista air kiss"[59] on the steps in front of a New York courthouse.

While the agreement remains confidential, some of the terms have been made public. Warnaco was able to retain its Calvin Klein licenses, but Calvin Klein was able to regain some of the creative control he had ceded in the original license. The agreement opens:

IT IS HEREBY AGREED by and between Calvin Klein and Warnaco as follows:

1. Calvin Klein and Warnaco agree to work together for their mutual benefit under their existing license and other agreements, except to the extent that those agreements are modified by the terms of this Settlement Agreement.

2. a. Beginning in calendar year 2002, Warnaco will limit its annual gross sales of Calvin Klein jeanswear to mass merchandisers (defined as, for example, KMart, Wal-Mart and Target) and/or warehouse clubs so that the percentage of such sales does not exceed ***% of Warnaco's total gross sales of Calvin Klein jeanswear in 2002 (and the percentage of sales other than excess and close-outs to such channels does not exceed ***% of total gross sales) and ***% in 2003 and thereafter (and the percentage of sales other than excess and close-outs to such channels does not exceed ***% of total gross sales). ***.This provision is without prejudice to the positions of the parties as to the meaning of the license terms.[60]

Red ink and golden parachute

When Linda Wachner forcibly took over the reins of Warnaco, she reduced the company’s debt by 35% within four years.[61] After her mid-1990s acquisition spree, however, Wachner led the clothing powerhouse once again to the brink of collapse. It was under her management that in 1995 Warnaco failed to make the Fortune 500 for the first time in nearly 30 years. Time Magazine referred to Warnaco’s reacquisition of Authentic Fitness as “financial gymnastics that helped prop up Wachner's bank account but ultimately loaded Warnaco's balance sheet with an extra $600 million in debt.[62]" Between 1998 and 2000, Warnaco’s stock had lost about 75% of its value, yet Wachner continued to draw a base salary of $2.7 million with an additional $12.5 million in bonuses and private stock.[63]

Upon her ouster as CEO, Wachner was denied her contractual $25 million golden parachute. She sued the company and in 2002 she accepted $3.5 million in new Warnaco stock and $200,000 in cash, which she said she would donate to cancer research.[64] Wachner stayed on the board of directors until her term expired in 2003.

Current licenses

Adapted from the Warnaco 2009 Annual Report:[65]

[Warnaco Group, Inc.] owns and licenses a portfolio of highly recognized brand names. The trademarks owned or licensed in perpetuity by the Company generated approximately 45% of the Company’s revenues during Fiscal 2009. Brand names the Company licenses for a term generated approximately 55% of its revenues during Fiscal 2009. Owned brand names and brand names licensed for extended periods (at least through 2044) accounted for over 89% of the Company’s net revenues in Fiscal 2009. The Company’s highly recognized brand names have been established in their respective markets for extended periods and have attained a high level of consumer awareness.

The following table sets forth the Company’s trademarks and licenses as of 2 January 2010:

Owned trademarks

- Warner’s

- Olga

- Body Nancy Ganz/Bodyslimmers

- Calvin Klein and formatives (beneficially owned for men’s/women’s/children’s underwear, loungewear and sleepwear)

Trademarks licensed in perpetuity

| Trademark | Territory |

|---|---|

| Speedoa | United States, Canada, Mexico, Caribbean Islands |

| Fastskin (secondary Speedo mark) | United States, Canada, Mexico, Caribbean Islands |

Trademarks licensed for a term

| Trademark | Territory | Expires |

|---|---|---|

| Calvin Klein (for men’s/women’s/juniors’ jeans and certain jeans-related products)b | North, South and Central America | December 31, 2044 |

| CK/Calvin Klein Jeans (for retail stores selling men’s/women’s/juniors’ jeans and certain jeans-related products and ancillary products bearing the Calvin Klein marks)b | Canada, Mexico and Central and South America | December 31, 2044 |

| CK/Calvin Klein (for bridge clothing, bridge, accessories and retail stores selling bridge clothing and accessories)c | All countries constituting European Union, Norway, Switzerland, Monaco, Vatican City, Liechtenstein, Iceland and parts of Eastern Europe, Russia, Middle East and Africa | December 31, 2046 |

| CK/Calvin Klein (for retail stores selling bridge accessories and jeans accessories)d | Central and South America (excluding Mexico) Europe and Asia | December 31, 2044 |

| Calvin Klein and CK/Calvin Klein (for men’s/women’s/children’s jeans and other related clothing as well as retail stores selling such items and ancillary products)c | Western Europe including Ireland, Great Britain, France, Monte Carlo, Germany, Spain, Portugal, Andorra, Italy, San Marino, Vatican City, Benelux, Denmark, Sweden, Norway, Finland, Austria, Switzerland, Lichtenstein, Greece, Cyprus, Turkey and Malta and parts of Eastern Europe, Russia, the Middle East and Africa, Japan, China, South Korea and “Rest of Asia” (Hong Kong, Thailand, Australia, New Zealand, Philippines, Taiwan, Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia, New Guinea, Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, Macau and the Federated State of Micronesia) | December 31, 2046 |

| CK/Calvin Klein (for independent or common internet sites for the sale of jeans and accessories)d | North America, Europe and Asia | December 31, 2046 |

| CK/Calvin Klein (for independent or common internet sites for the sale of jeans and accessories)d | Central and South America (excluding Mexico) | December 31, 2044 |

| Calvin Klein (for jeans accessories)c | All countries constituting European Union, Norway, Switzerland, Monte Carlo, Vatican City, Liechtenstein, Iceland and parts of Eastern Europe, Russia, Middle East, Africa and Asia | December 31, 2046 |

| Chaps (for men’s sportswear, jeanswear, activewear, sport shirts and men’s swimwear)e | United States, Canada, Mexico, Puerto Rico and Caribbean Islands | December 31, 2018 |

| Calvin Klein and CK/Calvin Klein (for women’s and juniors’ swimwear) | Worldwide with respect to Calvin Klein; Worldwide in approved forms with respect to CK/Calvin Klein | December 31, 2014 |

| Calvin Klein (for men’s swimwear) | Worldwide | December 31, 2014 |

| Lifeguard (for clothing excluding underwear and loungewear)f | Worldwide (United States, Canada, Mexico, Caribbean Islands and all other countries where trademark filings are or will be made) | June 30, 2030 |

Notes

^a Licensed in perpetuity from Speedo International, Ltd. (“SIL”).

^b Expiration date reflects a renewal option, which permits the Company to extend for an additional ten-year term through 31 December 2044 (subject to compliance with certain terms and conditions).

^c In January 2006, the Company acquired the companies that operate the license and related wholesale and retail businesses of Calvin Klein Jeans and accessories in Europe and Asia and the CK/Calvin Klein “bridge” line of sportswear and accessories in Europe. In connection with the acquisition, the Company acquired various exclusive license agreements. In addition, the Company entered into amendments to certain of its existing license agreements with Calvin Klein, Inc. (in its capacity as licensor).

^d By agreement dated 31 January 2008, the Company acquired the rights to operate CK/Calvin Klein retail stores for the sale of bridge and jeans accessories (in countries constituting Europe, Asia and Central and South America (excluding Mexico)) as well as the rights to operate CK/Calvin Klein independent or common internet sites for the sale of jeans and jeanswear accessories in the Americas (excluding Mexico), Europe and Asia.

^e Expiration date reflects a renewal option, which permits the Company to extend for an additional five-year term beyond the current expiration date of 31 December 2013 (subject to compliance with certain terms and conditions) for the trademark Chaps and the Chaps mark and logo.

^f Expiration date reflects four successive renewal options of five years each (each subject to compliance with certain terms and conditions).

See also

References

- ↑ "Warnaco Group, Inc. > Our Company > FAQ". FAQ. Warnaco Group, Inc. Retrieved 21 August 2010.

- ↑ "LinkedIn". Warnaco Company Profile. LinkedIn. Retrieved 21 August 2010.

- ↑ "Warnaco Group, Inc.> Our Company > Executive Officers". Retrieved 15 January 2011.

- ↑ "The Warner Group, Inc. (WRC) People". Reuters.com. Thomson Reuters. Retrieved 21 August 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 "WARNACO Group 2011 Annual Report - Form 10-K - February 29, 2012." (PDF). secdatabase.com. Retrieved 16 May 2012.

- ↑ "PVH unites Calvin Klein lines in $2.8 billion deal". Reuters.com. Thomson Reuters. Retrieved 31 October 2012.

- ↑ "PVH Corp.". Pvh.com. Retrieved 17 February 2015.

- ↑ "Chapter XX". HISTORY OF THE TOWN OF CORTLANDVILLE. rootsweb.

- ↑ Edwards, Richard (1885). New York's Great Industries: Exchange and Commercial Review, Embracing Also Historical and Descriptive Sketch of the City, Its Leading Merchants and Manufacturers. New York: Historical Publishing Company. p. 114.

- ↑ 1897 Sears Roebuck & Co. Catalogue, p. 324, at Google Books

- ↑ U.S. Patent 168,304

- ↑ U.S. Patent 403,161

- ↑ "Dr. Warner's Sanitary Corset". Antique Corset Gallery. Retrieved 21 August 2010.

- ↑ Samuel Orcutt (1886). A History of the Old Town of Stratford and City of Bridgeport Connecticut, Volume 2. Fairfield County Historical Society. pp. 740–744.

- ↑ . "The four most popular corsets in America." (print). Harper's Bazaar. New York. Jan 1886. 818161. Retrieved 23 August 2010.

- ↑ "Dr Warner's Health Corset". The Week : a Canadian journal of politics, literature, science and arts. 1 (16): 255. 20 Mar 1884.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 "The Warnaco Group Inc. -- Company History". FundingUniverse. The Gale Group.

- ↑ Rosenberg, Jennifer. "Flappers in the Roaring Twenties". About.com: 20th Century. The New York Times Company. Retrieved 20 April 2010.

- ↑ Uplift: The Bra in America, p. 73, at Google Books

- ↑ The corset: a cultural history, p. 161, at Google Books

- ↑ Tripp, Julie (November 1, 1986). "White Stag to leave Portland after 102 years". The Oregonian. Portland, Oregon. p. 1.

- ↑ "Warnaco's Walker Is Named As Chief Executive Officer". Wall Street Journal. New York. 2 December 1976. Retrieved 20 August 2010.

- ↑ "Prescott Man Heads Warnaco, Inc.". Saturday Citizen. Ottawa. 23 July 1976. Retrieved 20 August 2010.

- 1 2 "WACHNER, LINDA JOY". American Women Managers and Administrators: A Selective Biographical Dictionary of Twentieth-Century Leaders in Business, Education, and Government. Greenwood Press. 1985. p. 279. ISBN 0-313-23748-4. Retrieved 20 August 2010.

- ↑ "Wachner, Linda — Overview, Personal Life, Career Details, Social and Economic Impact, Chronology: Linda Wachner". Online Encyclopedia. Retrieved 20 August 2010.

- 1 2 3 "Company History:Authentic Fitness Corporation". Retrieved 20 August 2010.

- ↑ Caminiti, Susan; Reese, Jennifer (15 June 1992). "AMERICA'S MOST SUCCESSFUL BUSINESSWOMAN Linda Wachner, the CEO of Warnaco, cut the debt, took the company public, and boosted the stock price 75%. Any wonder her holding is worth $72 million?". Fortune. New York: Time, Inc. ISSN 0015-8259. Retrieved 21 August 2010

- ↑ "The Warnaco Group, Inc. M&A History". Retrieved 21 August 2010.

- ↑ "COMPANY NEWS; WARNACO TO BUY COMPANY THAT MAKES CALVIN KLEIN JEANS". New York Times. New York: Arthur Ochs Sulzberger, Jr. 27 September 1997. Retrieved 21 August 2010.

- ↑ "COMPANY NEWS; WARNACO TO MAKE CALVIN KLEIN CHILDREN'S CLOTHING". New York Times. New York: Arthur Ochs Sulzberger, Jr. 19 May 1998. Retrieved 21 August 2010.

- ↑ Forbes, Steve; Prevas, John (18 June 2009). "The Price Of Arrogance: The ugly stepsister of success is often a loss of discipline". Forbes.com. ISSN 0015-6914. Retrieved 21 August 2010.

- ↑ Young, Vicki M. (21 November 2006). "ICONIX ACQUIRES OP BRAND FOR $54M.(Iconix Brand Group bought Ocean Pacific from Warnaco Group)". Women’s Wear Daily. Advance Publications. Retrieved 24 August 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "WARNACO GROUP INC /DE/ CIK#: 0000801351". United States Securities and Exchange Commission. Retrieved 24 August 2010.

- ↑ Christopher Elser (September 2009). "Olympic Record Holder Phelps Extends Speedo Contract Until 2013". Bloomberg.com. Bloomberg. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ↑ Deborah Belgum (2002). "Bathing suit manufacturer back in the swim with Speedo pact". Los Angeles Business Journal. 15 July.

- ↑ "Warnaco Can Sell Unit". New York Times. New York: Arthur Ochs Sulzberger, Jr. 22 January 2002. Retrieved 26 August 2010.

- ↑ Warnaco. "QUARTERLY REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934. FOR THE QUARTERLY PERIOD ENDED JULY 3, 2010". UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION FORM 10-Q. Warnaco Group, In. Archived from the original on 26 August 2010. Retrieved 26 August 2010.

- ↑ "Income Statement". IR Fundamentals. Warnaco Group, Inc.

- 1 2 3 Marcial, Gene (4 April 2010). "Inside Wall Street: Calvin Klein Is Making Warnaco Look Sharp". DailyFinance. AOL Money & Finance. Retrieved 24 August 2010.

- 1 2 "Swimwear up as Warnaco reports Quarter 2 surge". 10 August 2010. Retrieved 24 August 2010.

- ↑ Zacks Investment Research (6 August 2010). "Warnaco Beats, Raises Guidance". Stock Market News & Opinions. DailyMarkets.com. Retrieved 24 August 2010.

- ↑ Glass, Kathryn (5 August 2010). "Warnaco 2Q Beats Estimates, Raises Full-Year View". Markets. Fox Business. Retrieved 24 August 2010.

- ↑ Chip Brian (August 2010). "Warnaco is Among the Companies in the Apparel, Accessories & Luxury Industry With the Best Relative Performance (WRC, FOSL, VFC, COH, TRLG)". Stock Market Trends and Technical Analysis. Comtex News Network, Inc. Retrieved 25 August 2010.

- ↑ Rex Moore (August 2010). "The Top 10 Values in Consumer Durables". The Motley Fool. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- 1 2 3 "Corset Shop Strikers Roughly Handle Girl" (print). The Day. New London, CT: The Day Publishing Company. 17 August 1915. p. 7. Retrieved 25 August 2010.

- ↑ Jeffery Haydu (1991). Between Craft and Class: skilled workers and factory politics in the United States and Britain, 1890-1922. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 175. ISBN 0-520-06060-1.

- ↑ "Strike Ends" (print). Reading Eagle. Reading, PA: Reading Eagle Company. 18 August 1915. p. 5. Retrieved 25 August 2010.

The strikers originally demanded a 20 per cent increase.

- ↑ "Bridgeport Strike Ends" (print). Boston Evening Transcript. Reading, PA: Reading Eagle Company. 19 August 1915. p. 7. Retrieved 25 August 2010.

The strike of nearly 4,000 women and girl operators...

- 1 2 "Sweatshops Made in USA". Multinational Monitor. 20 (1/2): 4. 1999.

- 1 2 3 Nikki F. Bas; Medea Benjamin; Joannie C. Chang (January 2004). "Saipan Sweatshop Lawsuit Ends with Important Gains for Workers and Lessons for Activists". cleanclothes.org/news. The Clean Clothes Campaign. Retrieved 26 August 2010.

- ↑ (AP) (1999). "Saipan sweatshop workers file suit against U.S. retailers". The Victoria Advocate (14 January): 28.

- ↑ Michael Rubin (October 2000). "Summary of the Saipan Sweatshop Litigation". Sweatfree Communities. Global Exchange. Retrieved 26 August 2010.

- ↑ "Class suit vs Levi's thrown out". Saipan Tribune. Pacific Publications and Printing Inc. 10 January 2004. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

In April, Levi’s was the lone holdout in a landmark $20 million settlement involving 27 garment manufacturers and 27 retailers, including Nordstrom Inc. of Seattle. The settling parties admitted to no wrongdoing but agreed to pay about $6.4 million to factory workers employed on Saipan at various times since 1989, along with other settlement provisions.

- ↑ Securities and Exchange Commission vs. WILLIAM S. FINKELSTEIN, 04 CV (U.S. Dist (S.D.N.Y.) 10 May 2004) (““The press release, which reported “record results,” failed to disclose that Warnaco would be restating its financial results for the prior three years to correct a $145 million inventory overstatement”).

- 1 2 "SEC Brings Settled Action Against Warnaco's Former CFO for Aiding and Abetting Warnaco's Securities Fraud and Other Violations" (Press release). Securities and Exchange Commission. 11 May 2004. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ↑ >Securities and Exchange Commission vs. PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP, 04 CV (U.S. Dist (S.D.N.Y.) 10 May 2004) (““recorded on Warnaco’s books. PwC failed to object to Warnaco’s mischaracterization of the inventory overstatement as involving “start-up related costs.” PwC also incorporated the misleading description of the restatement into its own audit report on Warnaco’s fiscal year 1998 financial statements.””).

- ↑ Klein, Calvin (5 June 2000). "Calvin Klein Discusses His Fashion Empire". Larry King Live (Interview). Interview with Larry King. Atlanta, GA: CNN. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ↑ Patricia Sellers (2000). "Seventh Avenue Smackdown Fashion moguls Calvin Klein and Linda Wachner are going toe-to-toe in a bitter suit. The feud is as much about personality as it is about business". Fortune (4 September).

- ↑ House of Klein: fashion, controversy, and a business obsession, p. 169, at Google Books

- ↑ Calvin Klein Trademark Trust, et al. v. The Warnaco Group, Inc., et al., 00 Civ. 4052 (U.S. Dist. (S.D.N.Y.) 22 January 2001).

- ↑ J. P. Donlon (1994). "Queen of cash flow — interview with Warnaco CEO Linda J. Wachner". The Chief Executive (Jan–Feb).

- ↑ Daniel Eisenberg; Carole Buia (2001). "Linda Wachner: Washed Up At Warnaco?". Time. No. 25 June.

- ↑ Geoffrey Colvin (2000). "America's Worst Boards These six aren't just bad, they're horrible. So why don't shareholders throw the bums out? It isn't easy". Fortune (17 April).

- ↑ "Ex-Warnaco Executive Settles Pay Issue". New York Times. New York: Arthur Ochs Sulzberger, Jr. 19 November 2009. Retrieved 25 August 2010.

- ↑ Warnaco (2010). "2009 ANNUAL REPORT ON FORM 10-K" (pdf). Warnaco 2009 Annual Report: 1–3.

Further reading

- Woman's Hand-Book in Health and Disease By Lucien Calvin Warner, via Google Books, published in 1886.

- Talks upon practical subjects edited by Marion Harland, with chapter contributions from Lucien C. Warner, M.D. ("The Nerves") and Ira De Ver Warner, M.D. ("Clothing"); via Google Books, published in 1895.

- Personal memoirs of Lucien Calvin Warner, By Lucien Calvin Warner, via The Internet Archive, published in 1915.

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Warner Brothers Company. |

- Warnaco, Warnaco Group, Inc. corporate website