War in the Vendée

| Part of a series on |

| Persecutions of the Catholic Church |

|---|

|

|

The War in the Vendée (1793; French: Guerre de Vendée) was an uprising in the Vendée region of France during the French Revolution. The Vendée is a coastal region, located immediately south of the Loire River in western France. Initially, the war was similar to the 14th-century Jacquerie peasant uprising, but quickly acquired themes considered by the government in Paris to be counter-revolutionary, and Royalist. The uprising headed by the self-styled Catholic and Royal Army was comparable to the Chouannerie, which took place in the area north of the Loire.

The departments included in the uprising, called the Vendée Militaire, included the area between the Loire and the Layon rivers: Vendée (Marais, Bocage Vendéen, Collines Vendéennes), part of Maine-et-Loire west of the Layon, and the portion of Deux Sèvres west of the River Thouet. Having secured their pays, the deficiencies of the Vendean army became more apparent. Lacking a unified strategy (or army) and fighting a defensive campaign, from April onwards the army lost cohesion and its special advantages. Successes continued for some time: Thouars was taken in early May and Saumur in June; there were victories at Châtillon and Vihiers. After this string of victories, the Vendeans turned to a protracted siege of Nantes, for which they were unprepared and which stalled their momentum, giving the government in Paris sufficient time to send more troops and experienced generals.

Tens of thousands of civilians, Republican prisoners, and sympathizers with the revolution were massacred by both armies. Historians such as Reynald Secher have described these events as 'genocide,' but most scholars reject the use of the word as inaccurate. Ultimately, the uprising was suppressed using draconian measures. The historian François Furet concludes that the repression in the Vendée "not only revealed massacre and destruction on an unprecedented scale but also a zeal so violent that it has bestowed as its legacy much of the region's identity ... The war aptly epitomizes the depth of the conflict ... between religious tradition and the revolutionary foundation of democracy."[5]

Background

Class differences were not as great in the Vendée as in Paris or in other French provinces. In the rural Vendée, the local nobility seems to have been more permanently in residence and less bitterly resented than in other parts of France.[6] Alexis de Tocqueville noted that most French nobles lived in cities by 1789. An Intendants' survey showed one of the few areas where they still lived with the peasants was the Vendée.[7] Consequently, the conflicts that drove the revolution in Paris, for example, were also lessened in this particularly isolated part of France by the strong adherence of the population to their Catholic faith. Since common people of this region, or the peasants to be more specific, didn't have access to education like people in the city, they did not have these revolutionary thoughts that caused the French Revolution in the city. The people of the Vendée region solely depended on the Church's ideals so when the people in Paris wanted to take the church's influence away from the people's lives, they thought of this as unimaginable and started to cause some unrest in the region.[8] In 1791, two representatives on mission informed the National Assembly of the disquieting condition of Vendée, and this news was quickly followed by the exposure of a royalist plot organized by the Marquis de la Rouerie. It was not until the social unrest and the fear of The Terror (a period between 1793–94 where tens of thousands of people were beheaded by use of guillotine) combined with the external pressures from the Civil Constitution of the Clergy (1790) and the introduction of a levy of 300,000 on the whole of France, decreed by the National Convention in February 1793, that the region erupted.[9][10]

The Civil Constitution of the Clergy required all clerics to swear allegiance to it and, by extension, to the increasingly anti-clerical National Constituent Assembly. All but seven of the 160 bishops refused the oath, as did about half of the parish priests.[11] Persecution of the clergy and of the faithful was the first trigger of the rebellion; the second being conscription. Nonjuring priests were exiled or imprisoned and women on their way to Mass were beaten in the streets.[11] Religious orders were suppressed and Church property confiscated.[11] On 3 March 1793, virtually all the churches were ordered closed.[12] Soldiers confiscated sacramental vessels and the people were forbidden to place crosses on graves.[12] Nearly all the purchasers of church land were bourgeois; very few peasants benefited from the sales.[13]

The March 1793 conscription requiring Vendeans to fill their district's quota of the national total of 300,000 enraged the populace,[9] who took up arms instead as "The Catholic Army", "Royal" being added later, and fought for "above all the reopening of their parish churches with their former priests."[14]

Although town dwellers were more likely to support the Revolution in the Vendée,[15] support for the revolution among the rural peasantry was not unknown. Many lived on monastery properties, and they overwhelmingly embraced the Revolution after these lands were seized and redistributed among them by the republican government.[16]

Outbreak of revolt

There were other levy riots across France when regions started to draft men into the army in response to the Levy Decree in February. The reaction in the northwest in early March was particularly pronounced with large-scale rioting verging on insurrection. By early April, in areas north of the Loire, order had been restored by the revolutionary government, but south of the Loire in four departments that became known as the Vendée militaire there were few troops to control rebels and what had started as rioting quickly took on the form of a full insurrection led by priests and the local nobility.[17]

Within a few weeks the rebel forces had formed a substantial, if ill-equipped, army, the Royal and Catholic Army, supported by two thousand irregular cavalry and a few captured artillery pieces. The main force of the rebels operated on a much smaller scale, using guerrilla tactics, supported by the insurgents' unparalleled local knowledge and the good-will of the people.[18]

Geographic coverage

Geographically, the insurrection occurred within a rough quadrilateral approximately 60 miles (97 km) wide, with Cholet at its center. The territory defied description in the terms of the redistricting of 1790, nor did it align itself to descriptors used in the Ancien Régime; the heart of the movement lay in the forests, with Cholet at its center, in the wild districts of the old county of Anjou, in the Breton marshlands between Montaigu and the sea. It included parts of the old Poitiers and Tours, the departements of Maine-et-Loire, the Vendée, and Deux Sèvres, but never completely fell under insurgent control.[19]

Vendée military response

The revolt began in earnest in March 1793, as a rejection of the mass conscription. In February, the Convention had voted to approve a levy of three hundred thousand men, to be chosen by lot among the unmarried men in each commune. Thus, the arrival of recruiters reminded locals of the methods of the monarchy, aroused resistance nearly everywhere in the countryside, and set in motion the first serious signs of sedition. For the most part, much of this resistance was quelled quickly, but in the lower Loire, in the Mauges and in the Vendean bocage, the situation was more serious and more protracted. Youths from communes surrounding Cholet, a large textile town on the boundary between the two regions, invaded the town and killed the commander of the National Guard, a "patriotic" (pro-revolutionary) manufacturer. Within a week, violence had spread to the Breton marshlands; peasants overran the town of Machecoul on 11 March, and several hundred "patriots" were massacred. A large band of peasants under the leadership of Jacques Cathelineau and Jean-Nicolas Stofflet seized Saint-Florent-le-Vieil on 12 March. By mid-March, a minor revolt against conscription, had turned into an insurrection.[20]

The Republic was quick to respond, dispatching over 45,000 troops to the area. The first pitched battle was on the night of 19 March. A Republican column of 2,000, under general Louis Henri François de Marcé, moving from La Rochelle to Nantes, was intercepted north of Chantonnay near the Gravereau bridge (Saint-Vincent-Sterlanges), over the river le Petit-Lay.[21] After six hours of fighting, rebel reinforcements arrived and routed the Republican forces. In the north, on 22 March, another Republican force was routed near Chalonnes-sur-Loire.[22]

There followed a series of skirmishes and armed contacts:

Battle of Bressuire

On 3 May 1793 Bressuire fell to Vendéen forces led by La Rochejacquelein.[23]

Battle of Thouars

On 5 May 1793. The main clash took place on the Pont de Vrine, the bridge over the stream leading into Thouars. The Vendéens proved unable to take the bridge for six hours, until Louis Marie de Lescure (fighting in his first battle) showed himself alone on the bridge under enemy fire and encouraged his men to follow him, which they did, crossing the bridge. The Republicans there were taken from behind by the cavalry under Charles de Bonchamps, which had crossed the river at a ford. Despite the arrival of reinforcements, the Republicans were routed and withdrew towards the city. The insurgents, headed by Henri de La Rochejacquelein, took the rampart by force and poured into the city, and the Republican troops quickly capitulated. The Vendéens seized a large amount of arms and gunpowder, but allowed the captured Republican forces to leave, after having sworn to no longer fight in the Vendée and had their hair shaved off so they could be recognised lest they went back on their word and were recaptured.

Battle of Fontenay-le-Comte

On 25 May 1793 the Catholic and royalist army took Fontenay-le-Comte. Lescure led his men in a courageous charge under enemy fire, shouting 'Long live the king!' and braving cannonfire, which left him unharmed. Likewise La Rochejacquelein wore his distinctive three red handkerchiefs on his head, waist and neck even though the gunners in the Republican forces were aiming for them. Following the victory his friends decided to copy him and all decided to wear three red handkerchiefs too so that La Rochejacquelein could not be distinguished by the enemy in the future. After this the only Vendée towns remaining in the control of the Republic were Nantes and Les Sables d'Olonne.[24]

Battle of Saumur

On 9 June 1793, Vendean insurgents commanded by Jacques Cathelineau captured the town of Saumur from Louis-Alexandre Berthier. The victory gave the insurgents a massive supply of arms, including 50 cannon. This was the high point of the insurgency.[25] The Vendeans had never before attempted to take such a large town, and they captured it in a single day, inflicting heavy losses on its Republican defenders. Many prisoners were taken, some of whom went over to the Vendean cause, while many of the citizens fled to Tours.[26]

Battle of Nantes

On 24 June 1793, the commanders of the Catholic and royalist army issued an ultimatum to the mayor of Nantes, Baco de la Chapelle to surrender the city or they would massacre the garrison.[27] On 29 June they began an assault with forces of 40,000. Inside the city were Republicans from the surrounding countryside who had fled to Nantes for safety, and fortified the defenders with tales of the horrors the rebels inflicted on towns they managed to take. Baco de la Chapelle stood on a dustcart which he called the 'chariot of victory' to urge the people on, even after he had been wounded in the leg. Poor coordination between the four Vendean armies led by Charette, Bonchamps, Cathelineau and Lyrot hampered the assault, and Cathelineau's forces were delayed in their deployment by fighting along the Erdre river with a Republican battalion. Cathelineau himself was shot at the head of his forces, causing his men to lose heart and retreat, and ultimately the Vendeans were unable to take the city.[28] In October of the same year, in order to punish the prisoners that were sent to the region after they lost the city, John-Baptiste Carrier resorted to trying to have the prisoners die by shooting them in mass crowds, but when that wasn't fast enough, he had the prisoners round up and sent off into the Loire river in boats that the bottom of the boat would open and left them to drown.[29] In addition, woman that were not guilty of any crime were publicly humiliated by the revolutionary Jacobins by being unclothed and sometimes tied with men and were sent to their death. This was called a Republican Marriage. [30]

Battle of Châtillon-sur-Sèvre

In July 1793, Jean Baptiste Kléber arrived from Mainz with a veteran army to suppress the rising. At the First Battle of Châtillon, southeast of Cholet, he inflicted one of the first defeats on the insurgents.[31]

Battle of Vihiers

The Vendeans won a victory over the revolutionary army led by Santerre at the Battle of Vihiers on 18 July 1793.[32]

Battle of Luçon

The Battle of Luçon was actually a series of three engagements fought over four weeks, the first on 15 July and the last on 14 August 1793, between Republican forces under Augustin Tuncq and Vendean forces. The engagement on 14 August, fought near the town of Luçon was actually the conclusion of three engagements between Louis d'Elbée's Vendean insurgents and the Republican army. On 15 July, Claude Sandoz and a garrison of 800 had repulsed 5,000 insurgents led by d'Elbee; on 28 July, Tuncq drove off a second attempt; two weeks later, Tuncq and his 5,000 men routed 30,000 insurgents under the personal command of François de Charette.[33]

Battle of Montaigu

The Battle of Montaigu was fought on 21 September 1793 when the Vendéens attacked general Jean-Michel Beysser's French Republican division. Taken by surprise, this division fought back but lost 400 men, including many captured. Some of these prisoners were summarily executed by the Vendeens and their bodies later found in the castle wells by troops under Jean-Baptiste Kléber.

Second Battle of Tiffauges

The Battle of Tiffauges was fought on 19 September 1793 between Royalist military leaders against Republican troops under Jean-Baptiste Kléber and Canclaux.

Second Battle of Chatillon

The Second Battle of Châtillon was fought on 11 October 1793.

Battle of Tremblaye

The Battle of Tremblaye (15 October 1793) took place near Cholet during the war in the Vendée, and was a Republican victory over the Vendéens. The Vendean leader Lescure was seriously injured in the fighting.[34]

Defeat (October–December 1793)

On 1 August 1793, the Committee of Public Safety ordered General Jean-Baptiste Carrier to carry out a "pacification" of the region by complete physical destruction.[35] These orders were not carried out immediately, but a steady stream of demands for total destruction persisted.[35]

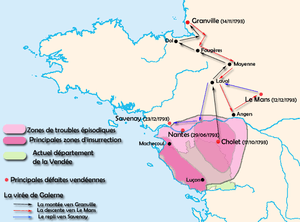

The Republican army was reinforced, benefiting from the first men of the levée en masse and reinforcements from Mainz. The Vendean army had its first serious defeat at the Battle of Cholet on 17 October; worse for the rebels, their army was split. In October 1793 the main force, commanded by Henri de la Rochejaquelein and numbering some 25,000 (followed by thousands of civilians of all ages), crossed the Loire, headed for the port of Granville where they expected to be greeted by a British fleet and an army of exiled French nobles. Arriving at Granville, they found the city surrounded by Republican forces, with no British ships in sight. Their attempts to take the city were unsuccessful. During the retreat, the extended columns fell prey to Republican forces; suffering from hunger and disease, they died in the thousands. The force was defeated in the last, decisive Battle of Savenay on 23 December.[36][37] Among those executed the following day was lieutenant-general Jacques Alexis de Verteuil.

But some historians assert that after the Savenay battle the rebellion was still going on.

[38]

After the Battle of Savenay (December 1793), General Westermann reported to his political masters at the Convention: "The Vendée is no more ... According to your orders, I have trampled their children beneath our horses' feet; I have massacred their women, so they will no longer give birth to brigands. I do not have a single prisoner to reproach me. I have exterminated them all."[37] Such killing of civilians would have been an explicit violation of the Convention's orders to Westermann.[39] Several thousand living Vendéan prisoners were being held by Westerman's forces though when the letter was supposedly written,[38] but some historians believe that letter of Westermann never existed.[40]

Aftermath

With the decisive Battle of Savenay (December 1793) came formal orders for forced evacuation; also, a 'scorched earth' policy was initiated: farms were destroyed, crops and forests burned and villages razed. There were many reported atrocities and a campaign of mass killing universally targeted at residents of the Vendée regardless of combatant status, political affiliation, age or gender.[41] One specific target were the woman of the region. Since they were seen, in a way, that they were carrying anti-revolutionary babies, they were seen as primary targets. [42]

From January to May 1794, 20,000 to 50,000 Vendean civilians were massacred by the Infernal columns of the general Louis Marie Turreau.[43][44][45]

Among those killed towards the end of the conflict were Saint Guillaume Repin and 98 other religious, many of whom were later beatified by the Catholic Church.[46]

In Anjou, directed by Nicolas Hentz and Marie Pierre Adrien Francastel, Republicans captured 11,000 to 15,000 Vendeans, 6,500 to 7,000 were shot or guillotined and 2,000 to 2,200 prisoners died from disease.[47]

Under orders from the Committee of Public Safety in February 1794, the Republican forces launched their final "pacification" effort (named Vendée-Vengé or "Vendée Avenged"): twelve columns, the colonnes infernales ("infernal columns") under Louis Marie Turreau, marched through the Vendée.[48] General Turreau inquired about "the fate of the women and children I will encounter in rebel territory", stating that, if it was "necessary to pass them all by sword", he would require a decree.[35] In response, the Committee of Public Safety ordered him to "eliminate the brigands to the last man, there is your duty..."[35]

The Convention issued conciliatory proclamations allowing the Vendeans liberty of worship and guaranteeing their property. General Hoche applied these measures with great success. He restored their cattle to the peasants who submitted, "let the priests have a few crowns", and on 20 July 1795 annihilated an émigré expedition which had been equipped in England and had seized Fort Penthièvre and Quiberon. Treaties were concluded at La Jaunaye (15 February 1795) and at La Mabillaie, and were fairly well observed by the Vendeans; no obstacle remained but the feeble and scattered remnant of the Vendeans still under arms and the Chouans. On 30 July 1796 the state of siege was raised in the western departments.[49]

Estimates of those killed in the Vendean conflict – on both sides – range between 117,000 and 450,000, out of a population of around 800,000.[50][51][52]

Later revolts

According to Theodore A. Dodge,[53] the war in the Vendée lasted with intensity from 1793 to 1799, when it was suppressed, but later broke out spasmodically especially in 1813, 1814 and 1815. During Napoleon's Hundred Days in 1815, some of the population of the Vendée remained loyal to Louis XVIII, forcing Napoleon – who was short of troops to fight the Waterloo Campaign – to send a force of 10,000 under the command of Jean Maximilien Lamarque to pacify the region.[54]

Genocide controversy

The popular historiography of the War in the Vendée is deeply rooted in conflicts between different schools of French historiography, and, as a result, writings on the uprising are generally highly partisan, coming down strongly in support of the revolutionary government or the Vendéen royalists.[55] This conflict originated in the 19th century between two groups of historians, the Bleus, named for their support of the republicans, who based their findings on archives from the uprising and the Blancs, named for their support of the monarchy and the Catholic Church, who based their findings on local oral histories.[56] The Bleus generally argued that the Vendée was not a popular uprising, but was the result of noble and clerical manipulation of the peasantry. One of the leaders of this school of thought, Charles-Louis Chassin, published eleven volumes of letters, archives, and other materials supporting this position. The Blancs, generally members of the former nobility and clergy themselves, argued (frequently using the same documents as Chassin, but also drawing from contemporary memoirs and oral histories) that the peasants were acting out of a genuine love for the nobility and a desire to protect the Catholic Church.[56]

This focus was popularized in the English-speaking world in 1986, with French historian Reynald Secher's A French Genocide: The Vendée. Secher argued that the actions of the French republican government during the War in the Vendée was the first modern genocide.[57] Secher's claims caused a minor uproar in France amongst scholars of modern French history, as many mainstream authorities on the period – both French and foreign – published articles rejecting Secher's claims.[58][59][60][61][62] Claude Langlois (of the Institute of History of the French Revolution) derides Secher's claims as "quasi-mythological".[63] Timothy Tackett of the University of California summarizes the case as such: "In reality ... the Vendée was a tragic civil war with endless horrors committed by both sides – initiated, in fact, by the rebels themselves. The Vendeans were no more blameless than were the republicans. The use of the word genocide is wholly inaccurate and inappropriate."[64] Hugh Gough (Professor of history at University College Dublin) called Secher's book an attempt at historical revisionism unlikely to have any lasting impact.[65]While some such as Peter McPhee roundly criticized Secher, including the assertion of commonality between the functions of the Republican government and Communist totalitarianism. Historian Pierre Chaunu expressed support for Secher's views,[66] describing the events as the first "ideological genocide".[67]

Critics of Secher's thesis have alleged that his methodology is flawed. McPhee asserted that these errors are as follows: (1) The war was not fought against Vendeans but Royalist Vendeans, the government relied on the support of Republican Vendeans; (2) the Convention ended the campaign after the Royalist Army was clearly defeated – if the aim was genocide, then they would have continued and easily exterminated the population; (3) Fails to inform the reader of atrocities committed by Royalist against Republicans in the Vendée; (4) Repeats stories now known to be folkloric myths as fact; (5) Does not refer to the wide range of estimates of deaths suffered by both sides, and that casualties were not "one-sided"; and more.[52]

Peter McPhee says that the pacification of the Vendée does not fit either the United Nations' CPPCG definition of genocide because the events happened during a civil war. He states that the war in the Vendée was not a one-sided mass killing and the Committee of Public Safety did not intend to exterminate the whole population of the Vendée; parts of the population were allied to the revolutionary government.[52]

Concerning the controversy, Michel Vovelle, a specialist on the French Revolution, remarked: "A whole literature is forming on "Franco-French genocide", starting from risky estimates of the number of fatalities in the Vendean wars ... Despite not being specialists in the subject, historians such as Pierre Chaunu have put all the weight of their great moral authority behind the development of an anathematizing discourse, and have dismissed any effort to look at the subject reasonably."[68]

Debate over the characterization of the Vendée uprising was renewed in 2007, when nine deputies introduced a measure to the Assemblée nationale to officially recognize the republican actions as genocidal.[69] The measure was strongly denounced by a group of leftist French historians as an attempt to use history to justify political extremism.[70]

Challenging the methodology

In the heart of the modern controversy lies Secher's evidence, which Charles Tilly analyzed in 1990.[71] Initially, Tilly maintains, Secher completed a thoughtful dissertation-style thesis about the revolutionary experience in his own village, La Chapelle-Basse-Mer, which lies near Nantes. In the published version of his thesis, he incorporated some of Tilly's own arguments: that conflicts within communities generalized into a region-wide confrontation of anti-revolutionary majority based in the countryside with a pro-revolutionary minority that had particular strength in the cities. The split formed with the application of the Civil Constitution of the Clergy and the oath to support it, in 1790–1792. From then, the local conflicts grew more sharply defined, over the choice between juring and non-juring priests. The conscription of March 1793, with the questionable exemption for Republican officials and National Guard members, broadened the anti-revolutionary coalition and brought the young men into action.[72]

With Le génocide français, Reynald Secher's thesis for the Doctorat d'État began with a generalization of the standard arguments to the whole region. Although La Chapelle-Basse-Mer served him repeatedly as a reference point, Secher illustrated his arguments with wide citations from national and regional archives to establish a broader frame of reference. Furthermore, he drew on graphic, nineteenth century accounts widely known to the historians of the Vendee: Carrier drownings and the "infernal columns of Turreau". Most importantly, however, Secher broke with conventional assessments by asserting on the basis of minimal evidence, Tilly claims, that the pre-revolutionary Vendée was more prosperous than the rest of France (to better emphasize the devastation of the war and the repression). He used dubious statistical methods to establish population losses and fatalities, statistical processes that inflated the number of people in the region, the number and value of houses, and the financial losses of the region. Secher's statistical procedure relied on three unjustifiable assumptions. First, Secher assumes a constant birth rate of about 37 per thousand of population, when actually, Tilly maintains, the population was declining. Second, Secher assumes no net migration; Tilly maintains that thousands fled the region, or at least shifted where they lived within the region. Finally, Secher understated the population present at the end of the conflict by ending it 1802, not 1794.[73]

Despite the criticism, a number of scholars continue the assertion of genocide. In addition to Secher and Chaunu, Kurt Jonassohn and Frank Chalk also consider it a case of genocide.[74] Further support comes from Adam Jones, who wrote in Genocide: A Comprehensive Introduction a summary of the Vendée uprising, supporting the view that it was a genocide: "the Vendée Uprising stands as a notable example of a mass killing campaign that has only recently been conceptualized as 'genocide'" and that while this designation "is not universally shared ... it seems apt in the light of the large scale murder of a designated group (the Vendéan civilian population)."[75] Pierre Chaunu[66] describes it as the first "ideological genocide".[76] Mark Levene, a historian who specializes in the study of genocide,[77] considers the Vendée "an archetype of modern genocide".[78] Other scholars who consider the massacres to be genocide include R.J. Rummel,[79] Jean Tulard,[80] and Anthony James Joes.[81]

Historiography

This relatively brief episode in French history has left significant traces on French politics, as the current argument on genocide suggests, yet it is reasonable to see the episode, Charles Tilly has claimed, in a far more benign light:

West's counterrevolution grew directly from the efforts of revolutionary officials to install a particular kind of direct rule in the region: a rule that practically eliminated nobles and priests from their positions as partly autonomous intermediaries, that brought the state's demands for taxes, manpower, and deference to the level of individual communities, neighborhoods, and households that gave the region's bourgeois political power they had never before wielded. In seeking to extend the state's rule to every locality, and to dislodge all enemies of that rule, French revolutionaries started a process that did not cease for twenty-five years.[82]

The Vendée revolt became an immediate symbol of confrontation between revolution and counterrevolution, and a source of unexpurgated violence. The region, and its towns, were eliminated; even the department name of Vendée was renamed Venge. Towns and cities were also renamed, but at heart, in villages and farms, the old names remained the same. Beyond the controversial interpretations of genocide, other historians posit the insurrection as a revolt against conscription that cascaded to include other complaints. For a period of several months, control of the Vendée slipped from the hands of Parisian revolutionaries. They ascribed the revolt to the resurgence of royalist ideas: when faced with insurrection of the people against the Revolution of the People, they were unable to see it as anything but an aristocratic plot. Mona Ozouf and François Furet maintain it was not. The entire territory, none of it unified under a single idea from the ancien regime, had never been a region morally at odds with the rest of the nation. It was not the fall of the old regime that aroused the population against the Revolution, but rather the construction of the new regime into locally unacceptable principles and forms: the new map of districts and departments, the administrative dictatorship, and above all the non-juring priests. Rebellion had first flared in August 1792, but had been immediately quelled. Even the regicide did not trigger insurrection. What did was the forced conscription. Although the Vendeans, to use the term loosely, wrote God and King large on their flags, they invested those symbols of their tradition with something other than regret for the lost regime.[83]

Film

The uprising in the Vendée was the subject of an independent feature film from Navis Pictures. The War of the Vendée (2012), written and directed by Jim Morlino, won awards for "Best Film For Young Audiences", (Mirabile Dictu International Catholic Film Festival – at the Vatican) and "Best Director" (John Paul II International Film Festival – Miami, FL). The Vendée Revolt was the setting for one of the BBC’s The Scarlet Pimpernel series entitled Valentin Gautier. (2002) The Vendée Revolt was also the setting for "The Frogs and the Lobsters", an episode of the television program Hornblower. It is set during the French revolutionary wars and very loosely based on the chapter of the same name in C. S. Forester's novel, Mr. Midshipman Hornblower and on the actual ill-fated Quiberon expedition of 1795.

See also

- Vendean leaders:

- Republican leaders:

- Other links:

- Chouannerie (another Royalist uprising)

- Drownings at Nantes (mass executions by drowning)

- Dechristianisation of France during the French Revolution

- Reign of Terror

- Cholet

- Clisson

- Fontenay-le-Comte

- La Roche-sur-Yon (capital of Vendée)

- Ninety-Three (novel by Victor Hugo)

References

- 1 2 3 4 Jacques Hussenet (dir.), « Détruisez la Vendée ! » Regards croisés sur les victimes et destructions de la guerre de Vendée, La Roche-sur-Yon, Centre vendéen de recherches historiques, 2007

- ↑ Jacques Dupâquier et A.Laclau, Pertes militaires, 1792–1830, in Atlas de la Révolution française, Paris 1992, p. 30.

- ↑ Jean-Clément Martin, La Terreur, part maudite de la Révolution, coll. Découvertes Gallimard (n° 566), 2010, p.82

- ↑ Jean-Clément Martin (dir.), Dictionnaire de la Contre-Révolution, Perrin, 2011, p.504.

- ↑ François Furet and Mona Ozouf, eds. A Critical Dictionary of the French Revolution (1989), p. 175.

- ↑ Schama, Simon (2004). Citizens. Penguin Books. p. 694. ISBN 0141017279.

- ↑ Alexis de Tocqueville, The Old Regime and the Revolution, pp 122–3

- ↑ Mignet, François (1826). History of the French revolution, from 1789 to 1814. ISBN 9781298067661.

- 1 2 James Maxwell Anderson (2007). Daily Life During the French Revolution, Greenwood Publishing Group, ISBN 0-313-33683-0. p. 205

- ↑ François Furet (1996). The French Revolution, 1770–1814: 1770–1814 Blackwell Publishing, France ISBN 0-631-20299-4. p. 124

- 1 2 3 Joes, Anthony James Resisting Rebellion: The History and Politics of Counterinsurgency 2006 University Press of Kentucky ISBN 0-8131-2339-9. p.51

- 1 2 Joes, p.52

- ↑ Charles Tilly, "Local Conflicts in the Vendée before the rebellion of 1793", French Historical Studies II, fall 1961, page 219

- ↑ Joes, pp. 52–53

- ↑ Charles Tilly, "Local Conflicts", p. 211

- ↑ Charles Tilly, "Civil Constitution and Counter-Revolution in southern Anjou," French Historical Studies, I no. 2 1959, p. 175

- ↑ Donald M. G. Sutherland (2003). The French Revolution and Empire: The Quest for a Civic Order, Blackwell Publishing France, ISBN 0-631-23363-6. p. 155

- ↑ General Hoche and Counterinsurgency

- ↑ François Furet, Mona Ozouf, A Critical Dictionary of the French Revolution, p. 165.

- ↑ Furet and Ozouf, p. 165–166.

- ↑ Louis Prévost (comte) de la Boutetière, Le chevalier de Sapinaud et les chefs vendéens du centre, Paris, 1869, page 25

- ↑ Jacques, Dictionary, P-Z, p. 810.

- ↑ Chronicle of the French Revolution p.336 Longman Group 1989

- ↑ Chronicle of the French Revolution, Longman 1989 p.338

- ↑ Jacques, Dictionary, P-Z, p. 916.

- ↑ Chronicle of the French Revolution, Longman 1989 p.342

- ↑ Chronicle of the French Revolution, Longman 1989 p.346

- ↑ Chronicle of the French Revolution, Longman 1989 p.348

- ↑ People's history of the french revolution. [S.l.]: Verso. 2014. ISBN 978-1-78168-589-1.

- ↑ Blakemore, Steven (1997). Crisis in representation : Thomas Paine, Mary Wollstonecraft, Helen Maria Williams, and the rewriting of the French Revolution. Madison: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 0838637140.

- ↑ Jacques, vol. A-E, p. 231.

- ↑ Chronicle of the French Revolution, Longman 1989 p.352

- ↑ Tony Jacques, Dictionary of Battles and Sieges: F-O, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2007, p. 604.

- ↑ Chronicle of the French Revolution, Longman 1989 p.372

- 1 2 3 4 Sutherland, Donald The French Revolution and Empire: The Quest for a Civic Order p. 222, 2003 Blackwell Publishing ISBN 0-631-23363-6

- ↑ Taylor, Ida Ashworth (1913). The tragedy of an army: La Vendée in 1793. Hutchinson & Co. p. 315. Retrieved 22 December 2011.

- 1 2 Mark Levene - The Rise of the West and the Coming of Genocide. Volume II: Genocide in the Age of the Nation State. I.B. Tauris, London - New York, 2005. Chapter 3: The Vendée – A Paradigm Shift? ; page 104. Retrieved 2 March 2017.

- 1 2 Jean-Clément Martin, Contre-Révolution, Révolution et Nation en France, 1789–1799, éditions du Seuil, collection Points, 1998, p. 219

- ↑ Jean-Clément Martin, Guerre de Vendée, dans l'Encyclopédie Bordas, Histoire de la France et des Français, Paris, Éditions Bordas, 1999, p 2084, et Contre-Révolution, Révolution et Nation en France, 1789–1799, p.218.

- ↑ Frédéric Augris, Henri Forestier, général à 18 ans, Éditions du Choletais, 1996

- ↑ Adam Jones, Genocide: A Comprehensive Introduction, (Routledge/Taylor & Francis Publishers 2006, p.7

- ↑ Blakemore, Steven (1997). Crisis in representation : Thomas Paine, Mary Wollstonecraft, Helen Maria Williams, and the rewriting of the French Revolution. Madison: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 0838637140.

- ↑ Louis-Marie Clénet, Les colonnes infernales, Perrin, collection Vérités et Légendes, 1993, p.221

- ↑ Roger Dupuy, La République jacobine, tome 3 de la Nouvelle histoire de la France contemporaine, p.268-269.

- ↑ Jacques Hussenet (dir.), « Détruisez la Vendée ! » Regards croisés sur les victimes et destructions de la guerre de Vendée, La Roche-sur-Yon, Centre vendéen de recherches historiques, 2007, p.140 et p.466

- ↑ John W. Carven, Martyrs for the Faith, Vincentian Heritage Journal, 8:2, Fall 1987

- ↑ Jacques Hussenet (dir.), « Détruisez la Vendée ! » Regards croisés sur les victimes et destructions de la guerre de Vendée, La Roche-sur-Yon, Centre vendéen de recherches historiques, 2007, p.452-453

- ↑ Masson, Sophie Remembering the Vendée (Godspy 2004. First published in "Quadrant" magazine Australia, 1996)

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition "Wars of the Vendee"

- ↑ 'State and Counterrevolution in France' – Charles Tilly. In: The French Revolution and the Birth of Modernity, edited by Ferenc Fehér. University of California Press; Berkeley – Los Angeles – Oxford, 1990. Retrieved 6 March 2017.

- ↑ Vive la Contre-Revolution!

- 1 2 3 McPhee, Peter Review of Reynald Secher, A French Genocide: The Vendée H-France Review Vol. 4 (March 2004), No. 26

- ↑ Napoleon by Theodore A. Dodge

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition Waterloo Campaign.

- ↑ Jean-Clément Martin, La Vendée et la Révolution. Accepter la mémoire pour écrire l'histoire, Perrin, collection Tempus, 2007, pp. 68–69

- 1 2 Jean-Clément Martin, La Vendée et la Révolution. Accepter la mémoire pour écrire l'histoire, Perrin, collection Tempus, 2007, pp. 70–71

- ↑ Secher, Reynald. A French Genocide: The Vendée, University of Notre Dame Press, (2003), ISBN 0-268-02865-6.

- ↑ Stefan Berger, Mark Donovan, Kevin Passmore (dir.), Writing National Histories—Western Europe Since 1800, Routledge, Londres, 1999, 247 pages, contribution by Julian Jackson. (jackson biography published by QMUL ),

- ↑ François Lebrun, « La guerre de Vendée : massacre ou génocide ? », L'Histoire, Paris, n°78, May 1985, p.93 to 99 et no. 81, September 1985, p. 99 to 101.

- ↑ Paul Tallonneau, Les Lucs et le génocide vendéen : comment on a manipulé les textes, éditions Hécate, 1993

- ↑ Claude Petitfrère, La Vendée et les Vendéens, Éditions Gallimard/Julliard, 1982.

- ↑ Voir Jean-Clément Martin, La Vendée et la France, Le Seuil, 1987.

- ↑ Claude Langlois, « Les héros quasi mythiques de la Vendée ou les dérives de l'imaginaire », in F. Lebrun, 1987, pp. 426–434, et « Les dérives vendéennes de l'imaginaire révolutionnaire », AESC, n°3, 1988, pp. 771–797.

- ↑ Voir l'intervention de Timothy Tackett, dans French Historical Studies, Autumn 2001, p. 572.

- ↑ Hugh Gough, "Genocide & the Bicentenary: the French Revolution and the revenge of the Vendée", (Historical Journal, vol. 30, 4, 1987, pp. 977–88.) p. 987.

- 1 2 Daileader, Philip and Philip Whalen, French Historians 1900–2000: New Historical Writing in Twentieth-Century France, pp. 105, 107, Wiley 2010

- ↑ Levene, Mark, Genocide in the Age of the Nation State: The rise of the West and the coming of Genocide, p. 118, I.B. Tauris 2005

- ↑ Vovelle, Michel (1987). Bourgeoisies de province et Revolution. Presses Universitaires de Grenoble. p. quoted in Féhér.

- ↑

- ↑ "La proposition de loi sur "le génocide vendéen", une atteinte à la liberté du citoyen.", archival link:

- ↑ Charles Tilly, "Chapter Three:State and Counterrevolution in France", found in Fehér, Ferenc, editor. The French Revolution and the Birth of Modernity. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990, pp. 49–63.

- ↑ Tilly, p. 60.

- ↑ Tilly, pp. 61–63.

- ↑ Jonassohn, Kurt and Solveig Bjeornson, Karin. Genocide and Gross Human Rights Violations. 1998, Transaction Publishers, ISBN 0765804174. p. 208.

- ↑ Jones, Adam. Genocide: A Comprehensive Introduction, Routledge/Taylor & Francis Publishers, (2006), ISBN 0-415-35385-8. Chapter 1, Section "The Vendée uprising", pp 6-7.

- ↑ Levene, Mark. Genocide in the Age of the Nation State: The rise of the West and the coming of Genocide, I. B. Tauris 2005. p. 118.

- ↑ Dr. Mark Levene, Southampton University, see "Areas where I can offer Postgraduate Supervision". Retrieved 9 February 2009.

- ↑ Shaw, Martin. What is genocide?, p. 107, Polity 2007

- ↑ Rummel, R. Death By government, p. 55, Transaction Publishers 1997

- ↑ Tulard, J.; Fayard, J.-F.; Fierro, A. Histoire et dictionnaire de la Révolution française, 1789–1799, Robert Laffont, Collection Bouquins, 1987, p.1113

- ↑ Joes, Anthony James. Guerrilla conflict before the Cold War, p. 63, Greenwood Publishing Group 1996

- ↑ Charles Tilly, "Chapter Three: State and Counterrevolution in France", found in Fehér, Ferenc, editor. The French Revolution and the Birth of Modernity. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990, p. 62.

- ↑ Furet and Ozouf, p. 166.

Bibliography

- Debord, Guy Panegyric Verso; (1991) ISBN 0-86091-347-3

- Davies, Norman Europe: A History Oxford University Press; (1996)

- Markoff, John. "The social geography of rural revolt at the beginning of the French Revolution." American Sociological Review (1985) 50#6 pp. 761–781 in JSTOR

- Markoff, John. "Peasant Grievances and Peasant Insurrection: France in 1789," Journal of Modern History (1990) 62#3 pp. 445–476 in JSTOR

- Secher, Reynald A French Genocide: The Vendée (Univ. of Notre Dame Press; 2003) ISBN 0-268-02865-6

- Tackett, Timothy. "The West in France in 1789: The Religious Factor in the Origins of the Counterrevolution," Journal of Modern History (1982) 54#4 pp. 715–745 in JSTOR

- Tilly, Charles. The Vendée: A Sociological Analysis of the Counter-Revolution of 1793 (1964)

Historiography

- Censer, Jack R. "Historians Revisit the Terror—Again." Journal of Social History 48#2 (2014): 383–403.

- Mitchell, Harvey. "The Vendée and Counterrevolution: A Review Essay," French Historical Studies (1968) 5#4 pp. 405–429 in JSTOR

in French

- Fournier, Elie Turreau et les colonnes infernales, ou, L'échec de la violence A. Michel; (1985) ISBN 2-226-02524-3