Walther Poppelreuter

Walther Poppelreuter (also incorrectly written in the literature Walther Poppelreuther and Walter Poppelreuter; born October 8, 1886 in Saarbrücken; died June 11, 1939 in Bonn[1]) was a German psychologist and neurologist. He dealt mainly with brain injuries of soldiers during the First World War and developed psychometric examination procedures that were used in the treatment of brain-injured patients and in industrial aptitude tests. He was among the first high school teachers who advocated openly for Nazism before the "seizure of power" (Machtergreifung). His psychometric tests are often used in visual neuropsychology, especially the Poppelreuter figure visual perceptual function test.[1]

Biography

The son of a high school director, Poppelreuter studied philosophy with a special emphasis on experimental psychology in Berlin and received his doctorate in 1908 in Königsberg. He then studied medicine and graduated in 1914.[2] He came on as assistant to Gustav Aschaffenburg at the Psychiatric Hospital of Cologne, which during the First World War was the Cologne fortress hospital for head injuries.[3]

In 1919, Poppelreuter moved to Bonn and became head of the newly founded "Institute for Applied Psychology"[4] - trade station for German brain-injured war victims. In 1922, he received a position at the University of Bonn as an associate professor of clinical psychology. Poppelreuter's work on brain injury gave him high professional recognition. He developed a series of psychometric examination methods that were used in industrial psychology and vocational counseling. His clinical interest was given to the possible treatment of neuropsychological dysfunction.

Against his resistance Poppelreuter's "Brain-Injured Institute" moved in 1925 to Düsseldorf; however, it had been vacant since 1924. Poppelreuter had given himself a sabbatical in 1923/24 and turned to ergonomic issues at Gelsenkirchen mine association. In 1925, he became head of the Institute of Work Psychology at RWTH Aachen University and founded in 1928 on Adolf Wallichs guided Chair for teaching a laboratory for industrial psycho-technique. Here he continued the experience he had gained from the inclusion of war-disabled in the rationalization of work processes in order.

In the winter semester 1931/32 he held a series of lectures on political psychology as applied psychology on the basis of Hitler's book Mein Kampf, which he in 1934 under the title Hitler, the political psychologist published. Hitler had told him in July 1932 in writing his joy that the first time his book will issue a lecture at a university.

In the Nazi period, Poppelreuter operated as a consultant of the National Socialist German Institute for Technical Work Research and Training in Düsseldorf. In Bonn, he served as Deputy Chairman of Psychology at the German Society. Shortly before his death, occupational and partisan judicial proceedings had been initiated against him for alcohol abuse and reprehensible means in a divorce dispute.

Contributions to psychology

Poppelreuter's law

Poppelreuter's Law is a law of physiological training that states that when teaching a skill requiring both speed and accuracy, it is better in the early stages to limit speed and practice until a certain degree of accuracy has been attained, and then gradually increase the speed.[5]

The law was invented and so named by Walther Poppelreuter in 1922. Subsequent research has invalidated the law, indicating that the neuromuscular patterns between the same activity performed slow and fast oftentimes are completely different and therefore unable to be trained simultaneously.

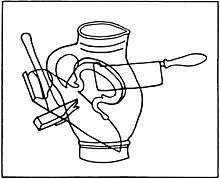

Poppelreuter figure visual perceptual function test

Poppelreuter invented the overlapping figures test in 1917 as one method of assessing brain injury incurred during World War I.[6] It is typical for people with apperceptive agnosia to have difficulty with the overlapping figures, but not for people with associative visual agnosia.[7]

Honors and criticism

The Walther-Poppelreuter Medal was named in his honor. In addition, houses and streets were named after him. Poppelreuter's Nazi past was only noticed by the publication of a book on child euthanasia in the Bonn children's institution in the public consciousness. In 1990, Hannelore Kohl returned the Poppelreuter medal conferred in 1986. In the series were streets in Oldenburg and Koblenz, as well as a named after Poppelreuter rehabilitation clinic in Vallendar renamed.

Published in 2003, the Aachen neurologist Gereon R. Fink in the journal The neurologist a text that Poppelreuters medical work as "not be overestimated" valued. The fact that Fink Nazi convictions and his behavior towards Lowenstein not taken into account in its assessment Poppelreuters, was criticized by Peter Frommelt, Linda Orth, and Ralf Forsbach.

In the district of Cologne Ostheim, there was a Poppelreuter Street since 1957. Due to Poppelreuter's involvement in Nazism, the road was renamed Josef-Poppelreuter Street, after the first director of the Roman division of the Wallraf-Richartz Museum.

References

- 1 2 Walther Poppelreuter (1990). Disturbances of lower and higher visual capacities caused by occipital damage: with special reference to the psychopathological, pedagogical, industrial, and social implications. Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-852190-7.

- ↑ Georg Lamberti: Die Psychotechnik in den zwanziger Jahren des 20. Jahrhunderts. In: Georg Lamberti (Hrsg.): Intelligenz auf dem Prüfstand: 100 Jahre Psychometrie. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2006, ISBN 3-525-46241-7, S. 49.

- ↑ Barbara A. Wilson (23 September 2005). Neuropsychological Rehabilitation: Theory and Practice. CRC Press. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-203-97101-7.

- ↑ Ulfried Geuter (18 December 2008). The Professionalization of Psychology in Nazi Germany. Cambridge University Press. p. 127. ISBN 978-0-521-10213-1.

- ↑ Hellebrandt, F. A. (1972). The physiology of motor learning. In R. N. Singer (Ed.), Readings in motor learning (pp. 397-409). Philadelphia, PA: Lea & Febiger.

- ↑ Muriel Deutsch Lezak (2004). Neuropsychological Assessment. Oxford University Press. p. 403. ISBN 978-0-19-511121-7.

- ↑ A.J. Larner (10 January 2012). Dementia in Clinical Practice: A Neurological Perspective: Studies in the Dementia Clinic. Springer. p. 48. ISBN 978-1-4471-2361-3.