Autostereogram

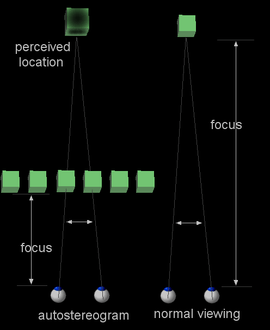

An autostereogram is a single-image stereogram (SIS), designed to create the visual illusion of a three-dimensional (3D) scene from a two-dimensional image. In order to perceive 3D shapes in these autostereograms, one must overcome the normally automatic coordination between accommodation (focus) and horizontal vergence (angle of one's eyes). The illusion is one of depth perception and involves stereopsis: depth perception arising from the different perspective each eye has of a three-dimensional scene, called binocular parallax.

The simplest type of autostereogram consists of horizontally repeating patterns (often separate images) and is known as a wallpaper autostereogram. When viewed with proper convergence, the repeating patterns appear to float above or below the background. The well-known Magic Eye books feature another type of autostereogram called a random dot autostereogram. One such autostereogram is illustrated above right. In this type of autostereogram, every pixel in the image is computed from a pattern strip and a depth map. A hidden 3D scene emerges when the image is viewed with the correct convergence.

Autostereograms are similar to normal stereograms except they are viewed without a stereoscope. A stereoscope presents 2D images of the same object from slightly different angles to the left eye and the right eye, allowing us to reconstruct the original object via binocular disparity. When viewed with the proper vergence, an autostereogram does the same, the binocular disparity existing in adjacent parts of the repeating 2D patterns.

There are two ways an autostereogram can be viewed: wall-eyed and cross-eyed.[lower-alpha 1] Most autostereograms (including those in this article) are designed to be viewed in only one way, which is usually wall-eyed. Wall-eyed viewing requires that the two eyes adopt a relatively parallel angle, while cross-eyed viewing requires a relatively convergent angle. An image designed for wall-eyed viewing if viewed correctly will appear to pop out of the background, while if viewed cross-eyed it will instead appear as a cut-out behind the background and may be difficult to bring entirely into focus.[lower-alpha 2]

History

In 1838, the British scientist Charles Wheatstone published an explanation of stereopsis (binocular depth perception) arising from differences in the horizontal positions of images in the two eyes. He supported his explanation by showing pictures with such horizontal differences, stereograms, separately to the left and right eyes through a stereoscope he invented based on mirrors. When people looked at these flat, two-dimensional pictures, they experienced the illusion of three-dimensional depth.[2][3]

Between 1849 and 1850, David Brewster, a Scottish scientist, improved the Wheatstone stereoscope by using lenses instead of mirrors, thus reducing the size of the device.[4]

Brewster also discovered the "wallpaper effect". He noticed that staring at repeated patterns in wallpapers could trick the brain into matching pairs of them as coming from the same virtual object on a virtual plane behind the walls. This is the basis of wallpaper-style "autostereograms" (also known as single-image stereograms).[2]

In 1851 H.W. Dove described "cross-eyed viewing as a stereoscope" with a standard pair of stereoscopic images.[5]

In 1939 Boris Kompaneysky[6] published the first random dot stereogram containing an image of the face of Venus,[7] intended to be viewed with a device.

In 1959, Bela Julesz,[8][9] a vision scientist, psychologist and MacArthur Fellow, invented the random dot stereogram while working at Bell Laboratories on recognizing camouflaged objects from aerial pictures taken by spy planes. At the time, many vision scientists still thought that depth perception occurred in the eye itself, whereas now it is known to be a complex neurological process. Julesz used a computer to create a stereo pair of random-dot images which, when viewed under a stereoscope, caused the brain to see 3D shapes. This proved that depth perception is a neurological process.[10][11]

Japanese designer Masayuki Ito, following Julesz, created a single image stereogram in 1970 and Swiss painter Alfons Schilling created a handmade single-image stereogram in 1974,[7] after creating more than one viewer and meeting with Julesz.[12] Having experience with stereo imaging in holography, lenticular photography, and vectography, he developed a random-dot method based on closely spaced vertical lines in parallax.[13]

In 1979, Christopher Tyler of Smith-Kettlewell Institute, a student of Julesz and a visual psychophysicist, combined the theories behind single-image wallpaper stereograms and random-dot stereograms (the work of Julesz and Schilling) to create the first black-and-white "random-dot autostereogram" (also known as single-image random-dot stereogram) with the assistance of computer programmer Maureen Clarke using Apple II and BASIC.[14] This type of autostereogram allows a person to see 3D shapes from a single 2D image without the aid of optical equipment.[15][16] In 1991 computer programmer Tom Baccei and artist Cheri Smith created the first color random-dot autostereograms, later marketed as Magic Eye.[17]

A computer procedure that extracts back the hidden geometry out of an autostereogram image was described by Ron Kimmel.[18] In addition to classical stereo it adds smoothness as an important assumption in the surface reconstruction.

How they work

Simple wallpaper

Stereopsis, or stereo vision, is the visual blending of two similar but not identical images into one, with resulting visual perception of solidity and depth.[19][20] In the human brain, stereopsis results from complex mechanisms that form a three-dimensional impression by matching each point (or set of points) in one eye's view with the equivalent point (or set of points) in the other eye's view. Using binocular disparity, the brain derives the points' positions in the otherwise inscrutable z-axis (depth).

When the brain is presented with a repeating pattern like wallpaper, it has difficulty matching the two eyes' views accurately. By looking at a horizontally repeating pattern, but converging the two eyes at a point behind the pattern, it is possible to trick the brain into matching one element of the pattern, as seen by the left eye, with another (similar looking) element, beside the first, as seen by the right eye. With the typical wall-eyed viewing, this gives the illusion of a plane bearing the same pattern but located behind the real wall. The distance at which this plane lies behind the wall depends only on the spacing between identical elements.[21]

Autostereograms use this dependence of depth on spacing to create three-dimensional images. If, over some area of the picture, the pattern is repeated at smaller distances, that area will appear closer than the background plane. If the distance of repeats is longer over some area, then that area will appear more distant (like a hole in the plane).

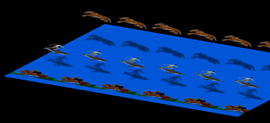

People who have never been able to perceive 3D shapes hidden within an autostereogram find it hard to understand remarks such as, "the 3D image will just pop out of the background, after you stare at the picture long enough", or "the 3D objects will just emerge from the background". It helps to illustrate how 3D images "emerge" from the background from a second viewer's perspective. If the virtual 3D objects reconstructed by the autostereogram viewer's brain were real objects, a second viewer observing the scene from the side would see these objects floating in the air above the background image.

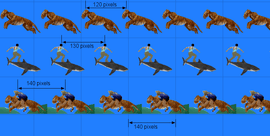

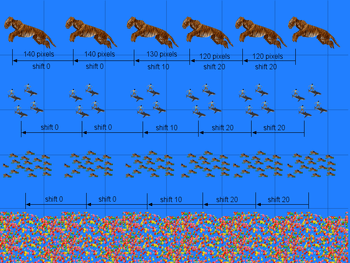

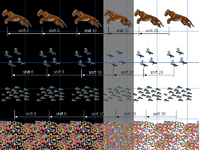

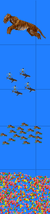

The 3D effects in the example autostereogram are created by repeating the tiger rider icons every 140 pixels on the background plane, the shark rider icons every 130 pixels on the second plane, and the tiger icons every 120 pixels on the highest plane. The closer a set of icons are packed horizontally, the higher they are lifted from the background plane. This repeat distance is referred to as the depth or z-axis value of a particular pattern in the autostereogram. The depth value is also known as Z-buffer value.

This picture illustrates how 3D shapes from an autostereogram "emerge" from the background plane, when the autostereogram is viewed with proper eye divergence. |

Depth or z-axis values are proportional to pixel shifts in the autostereogram. |

The brain is capable of almost instantly matching hundreds of patterns repeated at different intervals in order to recreate correct depth information for each pattern. An autostereogram may contain some 50 tigers of varying size, repeated at different intervals against a complex, repeated background. Yet, despite the apparent chaotic arrangement of patterns, the brain is able to place every tiger icon at its proper depth.

The brain can place every tiger icon on its proper depth plane. ( |

This image illustrates how an autostereogram is perceived by a viewer |

Depth maps

Depth map example autostereogram: Patterns in this autostereogram appear at different depth across each row. | ||||

Depth map greyscale example autostereogram: The black, gray and white colors in the background represent a depth map showing changes in depth across row. |

Pattern image | |||

Autostereograms where patterns in a particular row are repeated horizontally with the same spacing can be read either cross-eyed or wall-eyed. In such autostereograms, both types of reading will produce similar depth interpretation, with the exception that the cross-eyed reading reverses the depth (images that once popped out are now pushed in).

However, icons in a row do not need to be arranged at identical intervals. An autostereogram with varying intervals between icons across a row presents these icons at different depth planes to the viewer. The depth for each icon is computed from the distance between it and its neighbor at the left. These types of autostereograms are designed to be read in only one way, either cross-eyed or wall-eyed. All autostereograms in this article are encoded for wall-eyed viewing, unless specifically marked otherwise. An autostereogram encoded for wall-eyed viewing will produce inverse patterns when viewed cross-eyed, and vice-versus.[lower-alpha 2] Most Magic Eye pictures are also designed for wall-eyed viewing.

The wall-eyed depth map example autostereogram to the right encodes 3 planes across the x-axis. The background plane is on the left side of the picture. The highest plane is shown on the right side of the picture. There is a narrow middle plane in the middle of the x-axis. Starting with a background plane where icons are spaced at 140 pixels, one can raise a particular icon by shifting it a certain number of pixels to the left. For instance, the middle plane is created by shifting an icon 10 pixels to the left, effectively creating a spacing consisting of 130 pixels. The brain does not rely on intelligible icons which represent objects or concepts. In this autostereogram, patterns become smaller and smaller down the y-axis, until they look like random dots. The brain is still able to match these random dot patterns.

The distance relationship between any pixel and its counterpart in the equivalent pattern to the left can be expressed in a depth map. A depth map is simply a grayscale image which represents the distance between a pixel and its left counterpart using a grayscale value between black and white.[16] By convention, the closer the distance is, the brighter the color becomes.

Using this convention, a grayscale depth map for the example autostereogram can be created with black, gray and white representing shifts of 0 pixels, 10 pixels and 20 pixels, respectively as shown in the greyscale example autostereogram. A depth map is the key to creation of random-dot autostereograms.

Random-dot

Depth map |

Pattern |

A computer program can take a depth map and an accompanying pattern image to produce an autostereogram. The program tiles the pattern image horizontally to cover an area whose size is identical to the depth map. Conceptually, at every pixel in the output image, the program looks up the grayscale value of the equivalent pixel in the depth map image, and uses this value to determine the amount of horizontal shift required for the pixel.

One way to accomplish this is to make the program scan every line in the output image pixel-by-pixel from left to right. It seeds the first series of pixels in a row from the pattern image. Then it consults the depth map to retrieve appropriate shift values for subsequent pixels. For every pixel, it subtracts the shift from the width of the pattern image to arrive at a repeat interval. It uses this repeat interval to look up the color of the counterpart pixel to the left and uses its color as the new pixel's own color.[21]

Three raised rectangles appear on different depth planes in this autostereogram. ( |

Every pixel in an autostereogram obeys the distance interval specified by the depth map. |

Unlike the simple depth planes created by simple wallpaper autostereograms, subtle changes in spacing specified by the depth map can create the illusion of smooth gradients in distance. This is possible because the grayscale depth map allows individual pixels to be placed on one of 2n depth planes, where n is the number of bits used by each pixel in the depth map. In practice, the total number of depth planes is determined by the number of pixels used for the width of the pattern image. Each grayscale value must be translated into pixel space in order to shift pixels in the final autostereogram. As a result, the number of depth planes must be smaller than the pattern width.

The fine-tuned gradient requires a pattern image more complex than standard repeating-pattern wallpaper, so typically a pattern consisting of repeated random dots is used. When the autostereogram is viewed with proper viewing technique, a hidden 3D scene emerges. Autostereograms of this form are known as Random Dot Autostereograms.

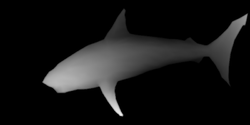

Smooth gradients can also be achieved with an intelligible pattern, assuming that the pattern is complex enough and does not have big, horizontal, monotonic patches. A big area painted with monotonic color without change in hue and brightness does not lend itself to pixel shifting, as the result of the horizontal shift is identical to the original patch. The following depth map of a shark with smooth gradient produces a perfectly readable autostereogram, even though the 2D image contains small monotonic areas; the brain is able to recognize these small gaps and fill in the blanks (illusory contours). While intelligible, repeated patterns are used instead of random dots, this type of autostereogram is still known by many as a Random Dot Autostereogram, because it is created using the same process.

The shark figure in this depth map is drawn with a smooth gradient. |

The 3D shark in this random-dot autostereogram has a smooth, round shape due to the use of depth map with smooth gradient. ( |

Animated

When a series of autostereograms are shown one after another, in the same way moving pictures are shown, the brain perceives an animated autostereogram. If all autostereograms in the animation are produced using the same background pattern, it is often possible to see faint outlines of parts of the moving 3D object in the 2D autostereogram image without wall-eyed viewing; the constantly shifting pixels of the moving object can be clearly distinguished from the static background plane. To eliminate this side effect, animated autostereograms often use shifting background in order to disguise the moving parts.

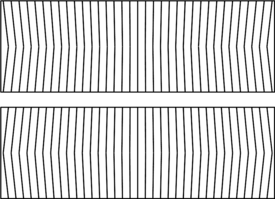

When a regular repeating pattern is viewed on a CRT monitor as if it were a wallpaper autostereogram, it is usually possible to see depth ripples. This can also be seen in the background to a static, random-dot autostereogram. These are caused by the sideways shifts in the image due to small changes in the deflection sensitivity (linearity) of the line scan, which then become interpreted as depth. This effect is especially apparent at the left hand edge of the screen where the scan speed is still settling after the flyback phase. On a TFT LCD, which functions differently, this does not occur and the effect is not present. Higher quality CRT displays also have better linearity and exhibit less or none of this effect.

Mechanisms for viewing

Much advice exists about seeing the intended three-dimensional image in an autostereogram. While some people may quickly see the 3D image in an autostereogram with little effort, others must learn to train their eyes to decouple eye convergence from lens focusing.

Not every person can see the 3D illusion in autostereograms. Because autostereograms are constructed based on stereo vision, persons with a variety of visual impairments, even those affecting only one eye, are unable to see the three-dimensional images.

People with amblyopia (also known as lazy eye) are unable to see the three-dimensional images. Children with poor or dysfunctional eyesight during a critical period in childhood may grow up stereoblind, as their brains are not stimulated by stereo images during the critical period. If such a vision problem is not corrected in early childhood, the damage becomes permanent and the adult will never be able to see autostereograms.[2][lower-alpha 3] It is estimated that some 1 percent to 5 percent of the population is affected by amblyopia.[23]

3D perception

Depth perception results from many monocular and binocular visual clues. For objects relatively close to the eyes, binocular vision plays an important role in depth perception. Binocular vision allows the brain to create a single Cyclopean image and to attach a depth level to each point in it.[10]

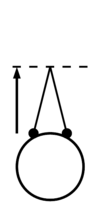

The two eyes converge on the object of attention. |

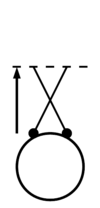

The brain creates a Cyclopean image from the two images received by the two eyes. |

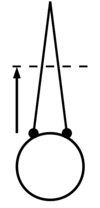

The brain gives each point in the Cyclopean image a depth value, represented here by a grayscale depth map. |

The brain uses coordinate shift (also known as parallax) of matched objects to identify depth of these objects.[21] The depth level of each point in the combined image can be represented by a grayscale pixel on a 2D image, for the benefit of the reader. The closer a point appears to the brain, the brighter it is painted. Thus, the way the brain perceives depth using binocular vision can be captured by a depth map (Cyclopean image) painted based on coordinate shift.

The eye operates like a photographic camera. It has an adjustable iris which can open (or close) to allow more (or less) light to enter the eye. As with any camera except pinhole cameras, it needs to focus light rays entering through the iris (aperture in a camera) so that they focus on a single point on the retina in order to produce a sharp image. The eye achieves this goal by adjusting a lens behind the cornea to refract light appropriately.

Stereo-vision based on parallax allows the brain to calculate depths of objects relative to the point of convergence. It is the convergence angle that gives the brain the absolute reference depth value for the point of convergence from which absolute depths of all other objects can be inferred.

Simulated 3D perception

The eyes normally focus and converge at the same distance in a process known as accommodative convergence. That is, when looking at a faraway object, the brain automatically flattens the lenses and rotates the two eyeballs for wall-eyed viewing. It is possible to train the brain to decouple these two operations. This decoupling has no useful purpose in everyday life, because it prevents the brain from interpreting objects in a coherent manner. To see a man-made picture such as an autostereogram where patterns are repeated horizontally, however, decoupling of focusing from convergence is crucial.[2]

By focusing the lenses on a nearby autostereogram where patterns are repeated and by converging the eyeballs at a distant point behind the autostereogram image, one can trick the brain into seeing 3D images. If the patterns received by the two eyes are similar enough, the brain will consider these two patterns a match and treat them as coming from the same imaginary object. This type of visualization is known as wall-eyed viewing, because the eyeballs adopt a wall-eyed convergence on a distant plane, even though the autostereogram image is actually closer to the eyes.[21] Because the two eyeballs converge on a plane farther away, the perceived location of the imaginary object is behind the autostereogram. The imaginary object also appears bigger than the patterns on the autostereogram because of foreshortening.

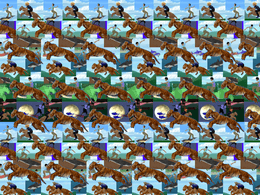

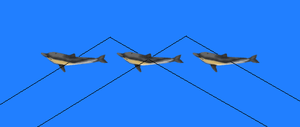

The following autostereogram shows three rows of repeated patterns. Each pattern is repeated at a different interval to place it on a different depth plane. The two non-repeating lines can be used to verify correct wall-eyed viewing. When the autostereogram is correctly interpreted by the brain using wall-eyed viewing, and one stares at the dolphin in the middle of the visual field, the brain should see two sets of flickering lines, as a result of binocular rivalry.[10]

The two black lines in this Autostereogram help viewers establish proper wall-eyed viewing, see right. |

When the brain manages to establish proper wall-eyed viewing, it will see two sets of lines. |

While there are six dolphin patterns in the autostereogram, the brain should see seven "apparent" dolphins on the plane of the autostereogram. This is a side effect of the pairing of similar patterns by the brain. There are five pairs of dolphin patterns in this image. This allows the brain to create five apparent dolphins. The leftmost pattern and the rightmost pattern by themselves have no partner, but the brain tries to assimilate these two patterns onto the established depth plane of adjacent dolphins despite binocular rivalry. As a result, there are seven apparent dolphins, with the leftmost and the rightmost ones appearing with a slight flicker, not dissimilar to the two sets of flickering lines observed when one stares at the 4th apparent dolphin.

Because of foreshortening, the difference in convergence needed to see repeated patterns on different planes causes the brain to attribute different sizes to patterns with identical 2D sizes. In the autostereogram of three rows of cubes, while all cubes have the same physical 2D dimensions, the ones on the top row appear bigger, because they are perceived as farther away than the cubes on the second and third rows.

Viewing techniques

If one has two eyes, fairly healthy eyesight, and no neurological conditions which prevent the perception of depth then one is capable of learning to see the images within autostereograms. "Like learning to ride a bicycle or to swim, some pick it up immediately, while others have a harder time."[24]

As with a photographic camera, it is easier to make the eye focus on an object when there is intense ambient light. With intense lighting, the eye can constrict the pupil, yet allow enough light to reach the retina. The more the eye resembles a pinhole camera, the less it depends on focusing through the lens.[lower-alpha 4] In other words, the degree of decoupling between focusing and convergence needed to visualize an autostereogram is reduced. This places less strain on the brain. Therefore, it may be easier for first-time autostereogram viewers to "see" their first 3D images if they attempt this feat with bright lighting.

Vergence control is important in being able to see 3D images. Thus it may help to concentrate on converging/diverging the two eyes to shift images that reach the two eyes, instead of trying to see a clear, focused image. Although the lens adjusts reflexively in order to produce clear, focused images, voluntary control over this process is possible.[25] The viewer alternates instead between converging and diverging the two eyes, in the process seeing "double images" typically seen when one is drunk or otherwise intoxicated. Eventually the brain will successfully match a pair of patterns reported by the two eyes and lock onto this particular degree of convergence. The brain will also adjust eye lenses to get a clear image of the matched pair. Once this is done, the images around the matched patterns quickly become clear as the brain matches additional patterns using roughly the same degree of convergence.

When one moves one's attention from one depth plane to another (for instance, from the top row of the chessboard to the bottom row), the two eyes need to adjust their convergence to match the new repeating interval of patterns. If the level of change in convergence is too high during this shift, sometimes the brain can lose the hard-earned decoupling between focusing and convergence. For a first-time viewer, therefore, it may be easier to see the autostereogram, if the two eyes rehearse the convergence exercise on an autostereogram where the depth of patterns across a particular row remains constant.

In a random dot autostereogram, the 3D image is usually shown in the middle of the autostereogram against a background depth plane (see the shark autostereogram). It may help to establish proper convergence first by staring at either the top or the bottom of the autostereogram, where patterns are usually repeated at a constant interval. Once the brain locks onto the background depth plane, it has a reference convergence degree from which it can then match patterns at different depth levels in the middle of the image.

The majority of autostereograms, including those in this article, are designed for divergent (wall-eyed) viewing. One way to help the brain concentrate on divergence instead of focusing is to hold the picture in front of the face, with the nose touching the picture. With the picture so close to their eyes, most people cannot focus on the picture. The brain may give up trying to move eye muscles in order to get a clear picture. If one slowly pulls back the picture away from the face, while refraining from focusing or rotating eyes, at some point the brain will lock onto a pair of patterns when the distance between them matches the current convergence degree of the two eyeballs.[15]

Another way is to stare at an object behind the picture in an attempt to establish proper divergence, while keeping part of the eyesight fixed on the picture to convince the brain to focus on the picture. A modified method has the viewer focus on their reflection on a reflective surface of the picture, which the brain perceives as being located twice as far away as the picture itself. This may help persuade the brain to adopt the required divergence while focusing on the nearby picture.[26]

For crossed-eyed autostereograms, a different approach needs to be taken. The viewer may hold one finger between their eyes and move it slowly towards the picture, maintaining focus on the finger at all times, until they are correctly focused on the spot that will allow them to view the illusion.

Terminology

- Stereogram and autostereogram

- Stereogram was originally used to describe as a pair of 2D images used in stereoscope to present a 3D image to viewers. The "auto" in autostereogram describes an image that does not require a stereoscope. The term stereogram is now often used interchangeably with autostereogram.[27] Dr. Christopher Tyler, inventor of the autostereogram, consistently refers to single image stereograms as autostereograms to distinguish them from other forms of stereograms.[16]

- Random dot stereogram (RDS)

- Random dot stereogram, describes a pair of 2D images containing random dots which, when viewed with a stereoscope, produced a 3D image. The term is now often used interchangeably with random dot autostereogram.[15][21]

- Single image stereogram (SIS)

- Single image stereogram (SIS). SIS differs from earlier stereograms in its use of a single 2D image instead of a stereo pair and is viewed without a device. Thus, the term is often used as a synonym of autostereogram. When the single 2D image is viewed with proper eye convergence, it causes the brain to fuse different patterns perceived by the two eyes into a virtual 3D image without, hidden within the 2D image, the aid of any optical equipment. SIS images are created using a repeating pattern.[16][28] Programs for their creation include Mathematica.[29][30]

- Random dot autostereogram/hidden image stereogram

- Is also known as single image random dot stereogram (SIRDS). This term also refers to autostereograms where the hidden 3D image is created using a random pattern of dots within one image,[28] shaped by a depth map within a dedicated stereogram rendering program.[31]

- Wallpaper autostereogram/object array stereogram/texture offset stereogram

- Wallpaper autostereogram is a single 2D image where recognizable patterns are repeated at various intervals to raise or lower each pattern's perceived 3D location in relation to the display surface. Despite the repetition, these are a type of single image autostereogram.

- A single image random text ASCII stereogram is an alternative to SIRDS using random ASCII text instead of dots to produce a 3D form of ASCII art.

- Map textured stereogram

- In a map textured stereogram, "a fitted texture is mapped onto the depth image and repeated a number of times" resulting in a pattern where the resulting 3D image is often partially or fully visible before viewing.[31]

See also

Notes

- 1 2 The terms "cross-eyed" and "wall-eyed" are borrowed from synonyms for various forms of strabismus, a condition where eyes do not point in the same direction when looking at an object. Wall-eyed viewing is informally known as parallel-viewing.

- 1 2 If a two-image stereogram, wallpaper, or random-dot autostereogram designed for wall-eyed viewing is viewed cross-eyed, or vice-versus, all details on the z-axis will be reversed – objects that were meant to be seen to rise above the background will appear to sink into it. However, there may be some incoherence due to overlapping (an object originally intended to project in front of another object will now project behind it). For example, the black lines in File:Stereogram Tut Simple.png.

- ↑ It is generally thought that amblyopia is a permanent condition, but NPR reports a case where a patient with amblyopia regains stereo vision (Susan R. Barry).[22]

- ↑ See aperture on similarity between aperture and pupil. See depth of field for relationship between aperture and lens.

References

- 1 2 3 Stephen M. Kosslyn, Daniel N. Osherson (1995). An Invitation to Cognitive Science, 2nd Edition - Vol. 2: Visual Cognition, p. 65 fig. 1.49. ISBN 978-0-262-15042-2.

- 1 2 3 4 Pinker, S. (1997). "The Mind's Eye", How the Mind Works, pp. 211–233. ISBN 0-393-31848-6.

- ↑ Wheatstone, Charles (1838). "Contributions to the Physiology of Vision, 1. On Some Remarkable, and Hitherto Unobserved, Phenomena of Binocular Vision", Philosophical Transactions. London: Royal Society of London. (Stereoscopy.com).

- ↑ Brewster, David (1856). The Stereoscope: Its History, Theory, and Construction, with Its Application to the Fine and Useful Arts and to Education, . J. Murray.

- ↑ https://books.google.nl/books?id=Wz4-AQAAMAAJ&dq=%22annalen%20der%20physik%22%20%22band%20LXXXIII%22&pg=PA183#v=onepage&q&f=false

- ↑ Kompaneysky, Boris N. (1939). "Depth sensations: Analysis of the theory of simulation by non exactly corresponding points", Bulletin of Ophthalmology (USSR) 14, pp. 90–105. (in Russian)

- 1 2 Weibel, Peter (2005). Beyond Art: A Third Culture: A Comparative Study in Cultures, Art and Science in 20th Century Austria and Hungary, p. 29. ISBN 978-3-211-24562-0.

- ↑ Julesz, Bela (1960). "Binocular depth perception of computer-generated patterns", Bell Technical Journal, p. 39.

- ↑ Julesz, Bela (1964). "Binocular depth perception without familiarity cues", Science, p. 145.

- 1 2 3 Julesz, B. (1971). Foundations of Cyclopean Perception, . Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-41527-9.

- ↑ Shimoj, S. (1994). Interview with Bela Julesz. In Horibuchi, S. (Ed.), Super Stereogram, pp. 85–93. San Francisco: Cadence Books. ISBN 1-56931-025-4.

- ↑ Weibel (2005), p. 125.

- ↑ Sakana, Itsuo (1994). Stereogram, pp. 75–76. Ed. Seiji Horibuchi and Yuki Inonue. San Francisco: Cadence Books. ISBN 978-0-929279-85-5

- ↑ Tyler, Christopher W. (1983). "Sensory processing of binocular disparity", Vergence Eye Movements, Basic and Clinical Aspects, . ed. L.M. Schor and K.J. Ciuffreda. London. 0409950327.

- 1 2 3 Magic Eye Inc. (2004). Magic Eye: Beyond 3D, . Kansas City: Andrews McMeel Publishing. ISBN 0-7407-4527-1.

- 1 2 3 4 Tyler, C.W. (1994). "The Birth of Computer Stereograms for Unaided Stereovision". In Horibuchi, S. (Ed.), Stereogram (pp. 83–89). San Francisco: Cadence Books. ISBN 0-929279-85-9.

- ↑ Innovation and Visualization: Trajectories, Strategies, and Myths. p. 211. Retrieved 2013-07-02.

- ↑ R. Kimmel. (2002) 3D Shape Reconstruction from Autostereograms and Stereo. Journal of Visual Communication and Image Representation, 13:324–333.

- ↑ Cassin, B. and Solomon, S. (1990). Dictionary of Eye Terminology, . Gainesville, Florida: Triad Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-937404-33-1

- ↑ Tyler, Christopher W., Lauren Barghout, and Leonid L. Kontsevich. "Computational reconstruction of the mechanisms of human stereopsis." Computational Vision Based on Neurobiology. International Society for Optics and Photonics, 1994.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Andrew A. Kinsman (1992). Random Dot Stereograms, . Rochester: Kinsman Physics. ISBN 0-9630142-1-8.

- ↑ Krulwich, Robert (2006). "Going Binocular: Susan's First Snowfall", NPR.org.

- ↑ Webber, Ann; Joanne Wood (November 2005). "Amblyopia - prevalence, natural history, functional effects and treatment". Clinical and Experimental Optometry. Retrieved 2006-07-17.

- ↑ Kosslyn and Osherson (1995), p. 64.

- ↑ McLin LN Jr, Schor CM (1988 Nov). "Voluntary effort as a stimulus to accommodation and vergence.", Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci., Vol. 29, No. 11, pp. 1739–46. PMID 3182206.

- ↑ Magic Eye Inc. (2004). Magic Eye: 3D Hidden Treasures, . Kansas City: Andrews McMeel Publishing. ISBN 0-7407-4791-6.

- ↑ Horibuchi, S. (1994). Stereogram, pp. 8–10, 22, 32, 36. San Francisco: Cadence Books. ISBN 0-929279-85-9. The term stereogram is used as a synonym of stereo pair, autostereogram, and random dot autostereogram throughout the book.

- 1 2 Open University Course Team (2008) The Science of the Senses, p. 183. Open University. ISBN 0-7492-1450-3.

- ↑ Donald Row, Talmage James Reid (2011). Geometry, Perspective Drawing, and Mechanisms, p. 142. ISBN 978-981-4343-82-4.

- ↑ Heikki Ruskeepää (2009). Mathematica Navigator: Mathematics, Statistics, and Graphics, p. 146. ISBN 978-0-12-374164-6. .

- 1 2 Gene Levine, Gary W. Priester (2008). Hidden Treasures: 3-D Stereograms, . ISBN 978-1-4027-5145-5.

Bibliography

- N. E. Thing Enterprises (1993). Magic Eye: A New Way of Looking at the World. Kansas City: Andrews and McMeel. ISBN 0-8362-7006-1

- Tyler, C.W. and Clarke, M.B. (1990) "The Autostereogram". Stereoscopic Displays and Applications, Proc. SPIE Vol. 1258:182–196.

- Marr, D. and Poggio, T. (1976). "Cooperative computation of stereo disparity". Science, 194:283–287; October 15.

- Julesz, B. (1964). "Binocular depth perception without familiarity cues". Science, 145:356–363.

- Julesz, B. (1963). "Stereopsis and binocular 3d Stereogram rivalry of contours". Journal of the Optical Society of America, 53:994–999.

- Julesz, B. and J.E. Miller. (1962). "Automatic stereoscopic presentation of functions of two variables". Bell System Technical Journal, 41:663–676; March.

- Scott B. Steinman, Barbara A. Steinman and Ralph Philip Garzia. (2000). Foundations of Binocular Vision: A Clinical perspective. McGraw-Hill Medical. ISBN 0-8385-2670-5

- Ron Kimmel. (2002) 3D Shape Reconstruction from Autostereograms and Stereo. Journal of Visual Communication and Image Representation, 13:324–333.

External links

-

Media related to Autostereograms at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Autostereograms at Wikimedia Commons - Scholarpedia article on autostereograms Peer-reviewed article on autostereograms by Christopher Tyler

- Stereograma - A Free Open-Source Cross-Platform Stereogram Generator

- Autostereograms - 3D Magic eye, SIRDS - Gallery Images

- Online ASCII stereogram generator

- Stereogram examples

- Animated autostereogram of two tori at the Wayback Machine (archived March 26, 2009)