Piriformis syndrome

| Piriformis syndrome | |

|---|---|

| |

| Location of piriformis syndrome within the body | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | Orthopedics, sports medicine |

| ICD-10 | G57.0 |

| ICD-9-CM | 355.0 |

| eMedicine | article/87545 |

| MeSH | D055958 |

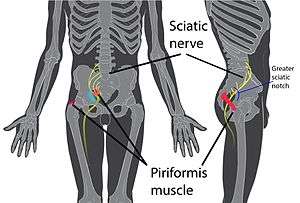

Piriformis syndrome is a somewhat controversial diagnosis of a neuromuscular disorder which is related to the sciatic nerve. According to the terms of the syndrome, the sciatic nerve becomes compressed or otherwise irritated by the piriformis muscle causing pain, tingling and numbness in the hip/ buttocks and along the path of the sciatic nerve descending the lower thigh and into the leg. It is one of the few conditions which causes posterior hip pain. The condition has no external signs. Diagnosis is often difficult due to few validated and standardized diagnostic tests, but two tests have been well-described and clinically validated: one is electrophysiological, called the FAIR-test,[1] which measures delay in sciatic nerve conductions when the piriformis muscle is stretched against it.[2]:41 The other is magnetic resonance neurography, a type of MRI that highlights inflammation and the nerves themselves.[3] Some say that the most important criterion is the exclusion of sciatica resulting from compression/irritation of spinal nerve roots, as by a herniated disc. However, compression may be present, but not causal, in the setting of sciatica due to piriformis syndrome.[4] Recovery time ranges between a few days to six weeks or more for complete recovery.

Possible causes of the syndrome are anatomical variations in the muscle-nerve relationship in the hip which place the piriformis muscle too close to the sciatic nerve (cadaver studies have shown this condition to be rather rare, however[5]), or from simple overuse or strain that causes swelling in the muscle and compression on the nerve.[6][7] Other research has suggested that pinching of the S1 nerve around the spine may cause the piriformis muscle to spasm secondarily; regardless, pain in the area of the piriformis often co-occurs with bona fide sciatica.[5]

One large scale formal prospective outcome trial found that the weight of the evidence-based medicine is that piriformis syndrome should be considered as a possible diagnosis when sciatica occurs without a clear spinal cause.[3][8] The need for controlled studies is supported by studies of spinal disc disease that show a high frequency of abnormal discs in asymptomatic patients.[9] Although damage to lower spinal discs is frequently associated with sciatic pain, such pain itself is not consistently associated with damaged discs, meaning other reasons (such as the swelling of the piriformis muscle) need to be considered, though spasms of the piriformis may also be caused by damage to the nerve roots of the sacrum— the causal relationship remains unclear, and the existence of the syndrome is itself open to question.

Signs and symptoms

In addition to causing gluteal pain that may radiate down buttock and the leg, the syndrome may present with pain that is relieved by walking with the foot on the involved side pointing outward. This position externally rotates the hip, lessening the stretch on the piriformis and relieving the pain slightly. Piriformis syndrome is also known as "wallet sciatica" or "fat wallet syndrome," as the condition can be caused or aggravated by sitting with a large wallet in the affected side's rear pocket.[10]

Pathophysiology

When the piriformis muscle shortens or spasms due to trauma or overuse, it can compress or strangle the sciatic nerve beneath the muscle. Generally, conditions of this type are referred to as nerve entrapment or as entrapment neuropathies; the particular condition known as piriformis syndrome refers to sciatica symptoms not originating from spinal roots and/or spinal disc compression, but involving the overlying piriformis muscle. In 17% of an assumed normal population the sciatic nerve passes through the piriformis muscle, rather than underneath it; however, in patients undergoing surgery for suspected piriformis syndrome such an anomaly was found only 16.2% of the time leading to doubt about the importance of the anomaly as a factor in piriformis syndrome.[11] Some researchers discount the importance of this relationship in the etiology of the syndrome.[11][12] Oddly, MRI findings have shown that both hypertrophy (unusual largeness) and atrophy (unusually smallness) of the piriformis muscle correlate with the supposed condition.[13]

It has been theorized that people who regularly exercise by running, bicycling, and other forward-moving activities may be more susceptible to developing piriformis syndrome if they do not engage in lateral stretching and strengthening exercises. When not balanced by lateral movement of the legs, repeated forward movements can lead to disproportionately weak hip abductors and tight adductors.[14] Thus, disproportionately weak hip abductors/gluteus medius muscles, combined with very tight adductor muscles, can cause the piriformis muscle to shorten and severely contract. This means the abductors on the outside cannot work properly and strain is put on the piriformis.[14] However, it is also possible that such people are actually experiencing small herniations in a spinal disc which then impinge on the sciatic nerve and cause the piriformis to spasm secondarily. Evidence for a specific relationship between the strength or weakness of certain hip muscles and sciatic nerve pain centered around the piriformis muscle remains scant. Also, this sports-related explanation is useless for understanding piriformis syndrome in those who are not unusually physically active (which is often the case).

The result of the piriformis muscle spasm can be impingement of not only the sciatic nerve but also the pudendal nerve.[15] The pudendal nerve controls the muscles of the bowels and bladder. Symptoms of pudendal nerve entrapment include tingling and numbness in the groin and saddle areas, and can lead to urinary and fecal incontinence.

Piriformis syndrome may also be associated with direct trauma to the piriformis muscle, such as in a fall or from a knife wound.[16]

Diagnosis

Piriformis syndrome occurs when the sciatic nerve is compressed or pinched by the piriformis muscle of the hip. It usually only affects one hip at a given time, though both hips may produce piriformis syndrome at some point in the patient's lifetime, and having had it once greatly increases the chance that it will recur in one hip or the other at some future point unless action is taken to prevent this. Indications include sciatica (radiating pain in the buttock, posterior thigh and lower leg) and the physical exam finding of tenderness in the area of the sciatic notch. If the piriformis muscle can be located beneath the other gluteal muscles, it will feel noticeably cord-like and will will be painful to compress or massage. The pain is exacerbated with any activity that causes flexion of the hip including lifting, prolonged sitting, or walking. The diagnosis is largely clinical and is one of exclusion. During a physical examination, attempts may be made to stretch the irritated piriformis and provoke sciatic nerve compression, such as the Freiberg test, the Pace test, the FABER test (flexion, abduction, external rotation), and the FAIR test (flexion, adduction, internal rotation). Conditions to be ruled out include herniated nucleus pulposus (HNP), facet arthropathy, spinal stenosis, and lumbar muscle strain.[7]

Diagnostic modalities such as CT scan, MRI, ultrasound, and EMG are mostly useful in excluding other conditions. However, magnetic resonance neurography is a medical imaging technique that can show the presence of irritation of the sciatic nerve at the level of the sciatic notch where the nerve passes under the piriformis muscle. Magnetic resonance neurography is considered "investigational/not medically necessary" by some insurance companies. Neurography can determine whether or not a patient has a split sciatic nerve or a split piriformis muscle – this may be important in getting a good result from injections or surgery. Image guided injections carried out in an open MRI scanner, or other 3D image guidance can accurately relax the piriformis muscle to test the diagnosis. Other injection methods such as blind injection, fluoroscopic guided injection, ultrasound, or EMG guidance can work but are not as reliable and have other drawbacks.

Prevention

The most common etiology of piriformis syndrome is that resulting from a specific previous injury due to trauma.[17] Large injuries include trauma to the buttocks while "micro traumas" result from small repeated bouts of stress on the piriformis itself.[18] To the extent that piriformis syndrome is the result of some type of trauma and not neuropathy, such secondary causes are considered preventable, especially those occurring in daily activities: according to this theory, periods of prolonged sitting, especially on hard surfaces, produce minor stress that can be relieved with bouts of standing. An individual's environment, including lifestyle factors and physical activity, determine susceptibility to trauma of any given type. Although empirical research findings on the subject have never been published, many believe that taking sensible precautions during high-impact sports and when working in physically demanding conditions may decrease the risk of experiencing piriformis syndrome, either by forestalling injury to the muscle itself or injury to the nerve root that causes it to spasm. In this vein, proper safety and padded equipment should be worn for protection during any type of regular, firm contact (i.e., American football, etc.). In the workplace, individuals are encouraged to make regular assessments of their surroundings and attempt to recognize those things in one's routine that might produce micro or macro traumas. No research has substantiated the effectiveness of any such routine, however, and participation in one may do nothing but heighten an individual's sense of worry over physical minutiae while have no effect in reducing the likeliness of experiencing or re-experiencing piriformis syndrome.

Other suggestions from some researchers and physical therapists have included prevention strategies include warming up before physical activity, practicing correct exercise form, stretching, and doing strength training, though these are often suggested for helping treat or prevent any physical injury and are not piriformis-specific in their approach[19] As with any type of exercise, it is thought that warmups will decrease the risk of injury during flexion or rotation of the hip. Stretching increases range of motion, while strengthening hip adductors and abductors theoretically allows the piriformis to tolerate trauma more readily.[17] However, to the extent that piriformis syndrome is actually related to sciatic nerve pain based in the spine, physically "warming up" the hip muscles will have no effect in preventing disc herniation and subsequent experience of pain along the sciatic pathway.

Treatment

Immediate though temporary relief of piriformis syndrome can usually be brought about by injection of a local anaesthetic into the piriformis muscle.[20] Symptomatic relief of muscle and nerve pain can also sometimes be obtained by non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and/or muscle relaxants, though the use of such medication or even more powerful prescription medication for relief of sciatica is often assessed by patients to be largely ineffective at relieving pain. Conservative treatment usually begins with stretching exercises, myofascial release, massage, and avoidance of contributory activities such as running, bicycling, rowing, heavy lifting, etc. Some clinicians recommend formal physical therapy, including soft tissue mobilization, hip joint mobilization, teaching stretching techniques, and strengthening of the gluteus maximus, gluteus medius, and biceps femoris to reduce strain on the piriformis. More advanced physical therapy treatment can include pelvic-trochanter isometric stretching, hip abductor,external rotator and extensor strengthening exercises, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), and massage physiotherapy of the piriformis muscle region.[21] One study of 14 people with what appeared to be piriformis syndrome indicated that rehabilitation programs that included physical therapy, low doses of muscle relaxants and pain relief medication were effective at alleviating most muscle and nerve pain caused by what the research subjects had been told was piriformis syndrome.[21] However, as this study included very few individuals and did not have a control group not receiving treatment (both serious methodological flaws), it provides no insight as to whether the pain in the piriformis would have simply dissipated on its own without any treatment at all and is therefore not only uninformative, it may actually be misleading. The injury is considered largely self-limiting and spontaneous recovery is usually on the order of a few days or a week to six weeks or longer if left untreated.[22]

Stretching

Most practitioners will agree that spasm/ strain/ pain in any muscle can often be treated by regular stretching exercise of that muscle, no matter the cause of the pain. Stretching is recommended every two to three waking hours. Anterior and posterior movement of the hip joint capsule may help optimize the patient's stretching capacity.[23] The muscle can be manually stretched by applying pressure perpendicular to the long axis of the muscle and parallel to the surface of the buttocks until the muscle is relaxed.[24] Another stretching exercise is to lie on the side opposite of the pain with the hip and knee of the upper leg flexed and adducted towards the ground while the torso is rotated so that the back of the upper shoulder touches the ground.[1] Physical Therapists may suggest stretching exercises that will target the piriformis, but may also include the hamstrings and hip muscles in order to adequately reduce pain and increase range of motion. Patients with piriformis syndrome may also find relief from applications of ice which will help reduce inflammation and so may help limit pressure on the sciatic nerve. This treatment can be helpful when pain starts or immediately after an activity that is likely to cause pain. As the length of time progresses, heat may provide temporary relief from many types of muscle pain and will temporarily increase muscle flexibility.

Strengthening

One research group reported a case study of a single individual with piriformis syndrome whose symptoms were entirely resolved through physical therapy sessions that worked to strengthen the hip abductors, external rotators and extensors.[25] This treatment involved three phases: non-weight bearing exercises, weight bearing exercises, and ballistic exercises. The purpose of non-weight bearing exercises is to focus on isolated muscle recruitment.[25] Ballistic and dynamic exercises consists of plyometrics. As this was a case study of a single individual, however, its statistical significance is meaningless and it may indicate nothing important regarding piriformis syndrome.

Failure of conservative treatments such as stretching and strengthening of the piriformis muscle or a high level of immediate pain intensity may bring into consideration various therapeutic injections such as local anesthetics (e.g., lidocaine), Anti-inflammatory drugs and/or corticosteroids, botulinum toxin (BTX, BOTOX), or a combination of the three, all of which have a well-documented effectiveness at relieving muscle-related pain.[7] Injection technique is a significant issue since the piriformis is a very deep seated muscle. A radiologist may assist in this clinical setting by injecting a small dose of medication containing a paralysing agent such as botulinum toxin under high-frequency ultrasound or CT control. This inactivates the piriformis muscle for 3 to 6 months, without resulting in leg weakness or impaired activity.[26] Though the piriformis muscle becomes inactivated, the surrounding muscles quickly take over its role without any noticeable change in strength or gait. Such treatments may be more or less curative (with no return to pain), or may have limited timespans of effectiveness.

Surgery

For rare cases with unrelenting chronic pain, surgery may be recommended. Surgical release of the piriformis muscle is often effective. Minimal access surgery using newly reported techniques has also proven successful in a large-scale formal outcome published in 2005.[27] As with injections, the deactivated/ excised muscle's role in leg movement is completely compensated for by surrounding hip muscles.

Failure of piriformis syndrome treatment may be secondary to an underlying obturator internus muscle injury.[28]

Epidemiology

Piriformis syndrome (PS) data is often confused with other conditions[17] due to differences in definitions, survey methods and whether or not occupational groups or general population are surveyed.[29] This causes a lack of group harmony about the diagnosis and treatment of PS, affecting its epidemiology.[30] In a study, 0.33% of 1293 patients with lower back pain cited an incident for PS.[30] A separate study showed 6% of 750 patients with the same incidence.[30] About 6% - 8% of lower back pain occurrences were attributed to PS,[1][7] though other reports concluded about 5% - 36%.[17] In a survey conducted on the general population, 12.2% - 27% included a lifetime occurrence of PS, while 2.2% - 19.5% showed an annual occurrence. However further studies show that the proportion of the sciatica, in terms of PS, is about 0.1% in orthopaedic practice.[29] This is more common in women with a ratio of 3 to 1[30] and most likely due to the wider quadriceps femoris muscle angle in the os coxae.[17] Between the years of 1991- 1994, PS was found to be 75% prevalent in New York, Connecticut, New Jersey, Pennsylvania; 20% in other American urban centers; and 5% in North and South America, Europe, Asia, Africa and Australia.[1] The common ages of occurrence happen between thirty and forty, and are scarcely found in patients younger than twenty;[30] this has been known to affect all lifestyles.[17]

Piriformis syndrome is often left undiagnosed and mistaken with other pains due to similar symptoms with back pain, quadriceps pain, lower leg pain, and buttock pain. These symptoms include tenderness, tingling and numbness initiating in lower back and buttock area and then radiating down to the thigh and to the leg.[31] A precise test for piriformis syndrome has not yet been developed and thus hard to diagnose this pain.[32] The pain is often initiated by sitting and walking for a longer period.[33] In 2012, 17.2% of lower back pain patients developed piriformis syndrome.[32] Piriformis syndrome does not occur in children, and is mostly seen in women of age between thirty and forty. This is due to hormone changes throughout their life, especially during pregnancy, where muscles around the pelvis, including piriformis muscles, tense up to stabilize the area for birth.[30] In 2011, out of 263 patients between the ages of 45 to 84 treated for piriformis syndrome, 53.3% were female. Females are two times more likely to develop piriformis syndrome than males. Moreover, females had longer stay in hospital during 2011 due to high prevalence of the pain in females. The average cost of treatment was $29,070 for hospitalizing average 4 days.[34]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 Fishman LM, Dombi GW, Michaelsen C, et al. (March 2002). "Piriformis syndrome: diagnosis, treatment, and outcome--a 10-year study". Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 83 (3): 295–301. PMID 11887107. doi:10.1053/apmr.2002.30622.

- ↑ Loren M. Fishman; Allen N Wilkins (4 November 2010). Functional Electromyography: Provocative Maneuvers in Electrodiagnosis. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-1-60761-020-5.

- 1 2 Filler AG, Haynes J, Jordan SE, et al. (February 2005). "Sciatica of nondisc origin and piriformis syndrome: diagnosis by magnetic resonance neurography and interventional magnetic resonance imaging with outcome study of resulting treatment". Journal of Neurosurgery. Spine. 2 (2): 99–115. PMID 15739520. doi:10.3171/spi.2005.2.2.0099.

- ↑ Fishman LM, Schaefer MP (November 2003). "The piriformis syndrome is underdiagnosed". Muscle & Nerve. 28 (5): 646–9. PMID 14571472. doi:10.1002/mus.10482.

- 1 2 Jennifer Baima (2009). Sports Injuries. Greenwood. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-313-35977-4.

- ↑ Piriformis Syndrome: Treatment & Medication

- 1 2 3 4 Kirschner JS, Foye PM, Cole JL (July 2009). "Piriformis syndrome, diagnosis and treatment". Muscle & Nerve. 40 (1): 10–8. PMID 19466717. doi:10.1002/mus.21318.

- ↑ Lewis AM, Layzer R, Engstrom JW, Barbaro NM, Chin CT (October 2006). "Magnetic resonance neurography in extraspinal sciatica". Archives of Neurology. 63 (10): 1469–72. PMID 17030664. doi:10.1001/archneur.63.10.1469.

- ↑ Deyo RA, Weinstein JN (February 2001). "Low back pain". The New England Journal of Medicine. 344 (5): 363–70. PMID 11172169. doi:10.1056/NEJM200102013440508.

- ↑ Piriformis Syndrome (Hip/Buttocks Pain)

- 1 2 Smoll NR (January 2010). "Variations of the piriformis and sciatic nerve with clinical consequence: a review". Clinical Anatomy. 23 (1): 8–17. PMID 19998490. doi:10.1002/ca.20893.

- ↑ Benzon HT, Katz JA, Benzon HA, Iqbal MS (June 2003). "Piriformis syndrome: anatomic considerations, a new injection technique, and a review of the literature". Anesthesiology. 98 (6): 1442–8. PMID 12766656. doi:10.1097/00000542-200306000-00022.

- ↑ Pope T, Bloem HL, Beltran J, Morrison WB, Wilson DJ (3 November 2014). Musculoskeletal Imaging. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 507. ISBN 978-0-323-27818-8.

- 1 2 http://www.drpribut.com/sports/piriformis.html%5B%5D%5B%5D

- ↑ http://www.chiroweb.com/mpacms/dc/article.php?id=44401%5B%5D%5B%5D

- ↑ Kuncewicz E, Gajewska E, Sobieska M, Samborski W (2006). "Piriformis muscle syndrome". Annales Academiae Medicae Stetinensis. 52 (3): 99–101; discussion 101. PMID 17385355.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Boyajian-O'Neill LA, McClain RL, Coleman MK, Thomas PP (November 2008). "Diagnosis and management of piriformis syndrome: an osteopathic approach". The Journal of the American Osteopathic Association. 108 (11): 657–64. PMID 19011229.

- ↑ Jawish RM, Assoum HA, Khamis CF (2010). "Anatomical, clinical and electrical observations in piriformis syndrome". Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery and Research. 5: 3. PMC 2828977

. PMID 20180984. doi:10.1186/1749-799X-5-3.

. PMID 20180984. doi:10.1186/1749-799X-5-3. - ↑ Keskula DR, Tamburello M (1992). "Conservative management of piriformis syndrome". Journal of Athletic Training. 27 (2): 102–10. PMC 1317145

. PMID 16558144.

. PMID 16558144. - ↑ Hayek SM, Shah BJ, Desai MJ, Chelimsky TC (16 April 2015). Pain Medicine: An Interdisciplinary Case-Based Approach. Oxford University Press. p. 240. ISBN 978-0-19-939081-6.

- 1 2 Ruiz-Arranz, J.L.; Alfonso-Venzalá, I.; Villalón-Ogayar, J. (2008). "Síndrome del músculo piramidal. Diagnóstico y tratamiento. Presentación de 14 casos" [Piriformis muscle syndrome. Diagnosis and treatment. Presentation of 14 cases]. Revista Española de Cirugía Ortopédica y Traumatología (in Spanish). 52 (6): 359–65. doi:10.1016/S1988-8856(08)70122-6.

- ↑ Sterling G. West (5 November 2014). Rheumatology Secrets. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 480. ISBN 978-0-323-03700-6.

- ↑ Klein, M. J. (2012). Physical medicine and rehabilitation for piriformis syndrome. In C. Lorenzo (Ed.),Medscape Reference: Drugs, Diseases and Procedures.

- ↑ Steiner C, Staubs C, Ganon M, Buhlinger C (April 1987). "Piriformis syndrome: pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment". The Journal of the American Osteopathic Association. 87 (4): 318–23. PMID 3583849.

- 1 2 Tonley JC, Yun SM, Kochevar RJ, Dye JA, Farrokhi S, Powers CM (February 2010). "Treatment of an individual with piriformis syndrome focusing on hip muscle strengthening and movement reeducation: a case report". The Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy. 40 (2): 103–11. PMID 20118521. doi:10.2519/jospt.2010.3108.

- ↑ Lang AM (2004). "Botulinum toxin type B in piriformis syndrome". Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 83 (3): 198–202. PMID 15043354. doi:10.1097/01.PHM.0000113404.35647.D8.

- ↑ "Spine Table of Contents Menu". Archived from the original on 2008-02-03. Retrieved 10 January 2014.

- ↑ "Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation for Piriformis Syndrome Treatment & Management". Retrieved 10 January 2014.

- 1 2 Hopayian K, Song F, Riera R, Sambandan S (December 2010). "The clinical features of the piriformis syndrome: a systematic review". European Spine Journal. 19 (12): 2095–109. PMC 2997212

. PMID 20596735. doi:10.1007/s00586-010-1504-9.

. PMID 20596735. doi:10.1007/s00586-010-1504-9. - 1 2 3 4 5 6 Papadopoulos EC, Khan SN (January 2004). "Piriformis syndrome and low back pain: a new classification and review of the literature". The Orthopedic Clinics of North America. 35 (1): 65–71. PMID 15062719. doi:10.1016/S0030-5898(03)00105-6.

- ↑ Wong LF, Mullers S, McGuinness E, Meaney J, O'Connell MP, Fitzpatrick C (August 2012). "Piriformis pyomyositis, an unusual presentation of leg pain post partum--case report and review of literature". The Journal of Maternal-fetal & Neonatal Medicine. 25 (8): 1505–7. PMID 22082187. doi:10.3109/14767058.2011.636098.

- 1 2 Kean Chen C, Nizar AJ (April 2013). "Prevalence of piriformis syndrome in chronic low back pain patients. A clinical diagnosis with modified FAIR test". Pain Practice. 13 (4): 276–81. PMID 22863240. doi:10.1111/j.1533-2500.2012.00585.x.

- ↑ Dere K, Akbas M, Luleci N (2009). "A rare cause of a piriformis syndrome". Journal of Back and Musculoskeletal Rehabilitation. 22 (1): 55–8. PMID 20023365. doi:10.3233/BMR-2009-0213.

- ↑ hcupnet.ahrq.gov,2011

- ↑ Hcupnet.ahrq.gov (2010, 2011)

External links

- Image sequence of piriformis muscle being injected under CT guidance

- Miller TA, White KP, Ross DC (September 2012). "The diagnosis and management of Piriformis Syndrome: myths and facts". The Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences. Le Journal Canadien Des Sciences Neurologiques. 39 (5): 577–83. PMID 22931697. doi:10.1017/s0317167100015298.

- Piriformis-Syndrome at NINDS