Federal Theatre Project

The Federal Theatre Project (1935–39) was a New Deal program to fund theatre and other live artistic performances and entertainment programs in the United States during the Great Depression. It was one of five Federal Project Number One projects sponsored by the Works Progress Administration. It was created not as a cultural activity but as a relief measure to employ artists, writers, directors and theater workers. It was shaped by national director Hallie Flanagan into a federation of regional theatres that created relevant art, encouraged experimentation in new forms and techniques, and made it possible for millions of Americans to see live theatre for the first time. The Federal Theatre Project ended when its funding was canceled after strong Congressional objections to the left-wing political tone of a small percentage of its productions.

Background

We let out these works on the vote of the people.

Part of the Works Progress Administration, the Federal Theatre Project was a New Deal program established August 27, 1935,[1]:29 funded under the Emergency Relief Appropriation Act of 1935. Of the $4.88 billion allocated to the WPA,[2] $27 million was approved for the employment of artists, musicians, writers and actors under the WPA's Federal Project Number One.[1]:44

Government relief efforts through the Federal Emergency Relief Administration and Civil Works Administration in the two preceding years were amateur experiments regarded as charity, not a theatre program. The Federal Theatre Project was a new approach to unemployment in the theatre profession. Only those certified as employable could be offered work, and that work was to be within the individual's defined skills and trades.[1]:15–16

"For the first time in the relief experiments of this country the preservation of the skill of the worker, and hence the preservation of his self-respect, became important," wrote Hallie Flanagan, director of the Federal Theatre Project.[1]:17 A theater professor at Vassar College who had studied the operation of government-sponsored theatre abroad for the Guggenheim Foundation,[1]:9 Flanagan was chosen to head the Federal Theatre Project by WPA head Harry Hopkins,[1]:20 a former classmate at Grinnell College.[1]:7 Roosevelt and Hopkins selected her despite considerable pressure to choose someone from the commercial theatre; they believed the project should be led by someone with academic credentials and a national perspective.[3]:39

Flanagan was given the daunting task of building a nationwide theater program to employ thousands of unemployed artists in as little time as possible. The problems of the theatre preceded the financial collapse of 1929. By that time it was already threatened with extinction due to the growing popularity of films and radio, but the commercial theatre was reluctant to adapt its practices.[3]:38 Many actors, technicians and stagehands had suffered since 1914, when movies began to replace stock, vaudeville and other live stage performances nationwide. Sound motion pictures displaced 30,000 musicians. In the Great Depression, people who had no money for entertainment found an entire evening of entertainment at the movies for 25 cents, while commercial theatre charged $1.10 to $2.20 admission to cover the cost of theater rental, advertising and fees to performers and union technicians. Unemployed directors, actors, designers, musicians and stagecrew took any kind of work they were able to find, whatever it paid, and charity was often their only recourse.[1]:13–14

"This is a tough job we're asking you to do," Hopkins told Flanagan at their first meeting in May 1935. "I don't know why I still hang on to the idea that unemployed actors get just as hungry as anybody else."[1]:7–9

Hopkins promised "a free, adult, uncensored theatre"[1]:28 — something Flanagan spent the next four years trying to build.[1]:29 She emphasized the development of local and regional theatre, "to lay the foundation for the development of a truly creative theatre in the United States with outstanding producing centers in each of those regions which have common interests as a result of geography, language origins, history, tradition, custom, occupations of the people."[1]:22–23

Operation

On October 24, 1935, Flanagan prefaced her instructions on the Federal Theatre's operation with a statement of purpose:

The primary aim of the Federal Theatre Project is the reemployment of theatre workers now on public relief rolls: actors, directors, playwrights, designers, vaudeville artists, stage technicians, and other workers in the theatre field. The far reaching purpose is the establishment of theatres so vital to community life that they will continue to function after the program of this Federal Project is completed.[4]

Within a year the Federal Theatre Project employed 15,000 men and women,[5]:174 paying them $23.86 a week.[6] During its nearly four years of existence it played to 30 million people in more than 200 theaters nationwide[5]:174 — renting many that had been shuttered — as well as parks, schools, churches, clubs, factories, hospitals and closed-off streets.[3]:40 Its productions totalled approximately 1,200, not including its radio programs.[1]:432 Because the Federal Theatre was created to employ and train people, not to generate revenue, no provision was made for the receipt of money when the project began. At its conclusion, 65 percent of its productions were still presented free of charge.[1]:434

The total cost of the Federal Theatre Project was $46 million.[3]:40

"In any consideration of the cost of the Federal Theatre," Flanagan wrote, "it should be borne in mind that the funds were allotted, according to the terms of the Relief Act of 1935, to pay wages to unemployed people. Therefore, when Federal Theatre was criticized for spending money, it was criticized for doing what it was set up to do."[1]:34–35

The Federal Theatre Project did not operate in every state, since many lacked a sufficient number of unemployed people in the theatre profession.[1]:434 The project in Alabama was closed in January 1937 when its personnel were transferred to a new unit in Georgia. Only one event was presented in Arkansas. Units created in Minnesota, Missouri and Wisconsin were closed in 1936; projects in Indiana, Nebraska, Rhode Island and Texas were discontinued in 1937; and the Iowa project was closed in 1938.[1]:434–436

Many of the notable artists of the time participated in the Federal Theatre Project, including Susan Glaspell who served as Midwest bureau director.[1]:266 The legacy of the Federal Theatre Project can also be found in beginning the careers of a new generation of theater artists. Arthur Miller, Orson Welles, John Houseman, Martin Ritt, Elia Kazan, Joseph Losey, Marc Blitzstein and Abe Feder are among those who became established, in part, through their work in the Federal Theatre. Blitzstein, Houseman, Welles and Feder collaborated on the controversial production, The Cradle Will Rock.

The Federal Theatre Project was the most costly of the Federal One projects, consuming 29.1 percent of Federal One's budget, which was itself less than three-fourths of one percent of the total WPA budget.

On June 30, 1939, the Federal Theatre Project ended when its funding was canceled, largely due to strong Congressional objections to the overtly left-wing political tones of less than 10 percent of the Federal Theatre Project productions.[1]:361–363

Living Newspaper

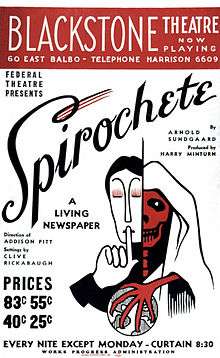

Living Newspapers were plays written by teams of researchers-turned-playwrights. These men and women clipped articles from newspapers about current events, often hot button issues like farm policy, syphilis testing, the Tennessee Valley Authority, and housing inequity. These newspaper clippings were adapted into plays intended to inform audiences, often with progressive or left-wing themes. Triple-A Plowed Under, for instance, attacked the U.S. Supreme Court for killing an aid agency for farmers. These politically themed plays quickly drew criticism from members of Congress.

Although the undisguised political invective in the Living Newspapers sparked controversy, they also proved popular with audiences. As an art form, the Living Newspaper is perhaps the Federal Theatre's most well-known work.

Problems with the Federal Theatre Project and Congress intensified when the State Department objected to the first Living Newspaper, Ethiopia, about Haile Selassie and his nation's struggles against Benito Mussolini's invading Italian forces. The U.S. government soon mandated that the Federal Theatre Project, a government agency, could not depict foreign heads of state on the stage for fear of diplomatic backlash. Playwright and director Elmer Rice, head of the New York office of the FTP, resigned in protest and was succeeded by his assistant, Philip W. Barber.

New productions

Numbers following the city of origin indicate the number of additional cities where the play was presented.

| Title | Author | City | Dates |

|---|---|---|---|

| Highlights of 1935 | Living Newspaper staff | New York | May 12–30, 1936[1]:390 |

| Injunction Granted | Living Newspaper staff | New York | July 24–October 20, 1936[1]:390 |

| Living Newspaper, First Edition | Cleveland Bronner | Norwalk, Conn. | June 1–July 2, 1936[1]:390 |

| Living Newspaper, Second Edition | Cleveland Bronner | Norwalk, Conn. | August 18–25, 1936[1]:390 |

| The Living Newspaper | Project staff | Cleveland | March 11–28, 1936[1]:390 |

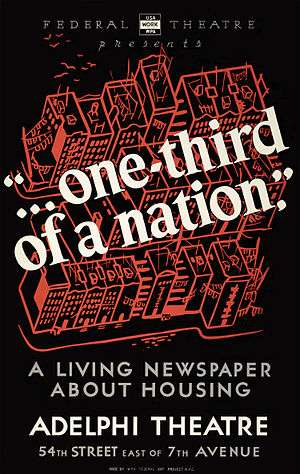

| One-Third of a Nation | Arthur Arent | New York + 9 | January 17–October 22, 1938[1]:390 |

| Power | Arthur Arent | New York + 4 | February 23–July 10, 1937[1]:390 |

| Spirochete | Arnold Sundgaard | Chicago + 4 | April 29–June 4, 1938[1]:390 |

| Triple-A Plowed Under | Living Newspaper staff | New York + 4 | March 14–May 2, 1936[1]:390 |

African-American theatre

The Negro Theatre Unit was part of the Federal Theatre Project and had units that were set up in cities throughout the United States. The units were located in four different geographical regions of the country. In the West, units were located in Seattle, Washington, and Los Angeles, California. In the East, units were located in New York City, New York, Boston, Massachusetts, Hartford, Connecticut, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and Newark, New Jersey. In the South, there were units in Raleigh, North Carolina, Durham, North Carolina, and Birmingham, Alabama. In the Midwest, units were located in Chicago, Illinois, Peoria, Illinois, and Cleveland, Ohio. The project provided employment and apprenticeships to black playwrights, directors, actors, and technicians. The project offered a much needed source of assistance for African-American theatre from 1935 to 1939. The project's inspiring purposes further influenced the founding within a year of the American Negro Theater, 1940 – 1949.

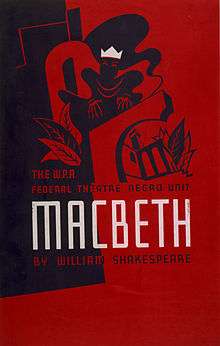

The Negro Theatre Unit of New York City was the best known. It was headquartered at the Lafayette Theatre in Harlem, where some 30 plays were presented. The first was Frank H. Wilson's folk drama, Walk Together Chillun (1936), about the deportation of 100 African-Americans from the South to the North to work for low wages. The second was Conjur' Man Dies (1936), a comedy-mystery adapted by Arna Bontemps and Countee Cullen from Rudolph Fisher’s novel. The most popular production was the third, which came to be called the Voodoo Macbeth (1936), director Orson Welles's adaptation of Shakespeare's play set on a mythical island suggesting the Haitian court of King Henri Christophe.[7]:179–180

New drama productions

Numbers following the city of origin indicate the number of additional cities where the play was presented.

| Title | Author | City | Dates |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accident Policy | Arthur Akers | Birmingham | July 31–August 3, 1936[1]:392 |

| Advent and Nativity of Christ | adapted by Hedley Gordon Graham | New York | December 20–24, 1937[1]:392 |

| Bassa Moona (The Land I Love) | Momodu Johnson, Norman Coker | New York | December 8, 1936 – March 20, 1937[1]:392 |

| Big White Fog | Theodore Ward | Chicago | April 7–May 30, 1938[1]:392 |

| Black Empire | Christine Ames, Clarke Painter | Los Angeles + 1 | March 16–July 19, 1936[1]:392 |

| The Case of Philip Lawrence | George MacEntree | New York | June 8–July 31, 1937[1]:392 |

| Conjur' Man Dies | Rudolph Fisher, adapted by Arna Bontemps and Countee Cullen[7]:179 | New York + 1 | March 11–July 4, 1936[1]:392 |

| Did Adam Sin? | Lew Payton | Chicago | April 30–May 14, 1936[1]:392 |

| An Evening with Dunbar | Paul Laurence Dunbar, adapted by project staff | Seattle | October 31–December 17, 1938[1]:392 |

| Great Day | M. Wood | Birmingham | October 7, 1936[1]:393 |

| Haiti | William DuBois | New York + 1 | March 2–November 5, 1938[1]:393 |

| Heaven Bound | Nellie Lindley Davis, adapted by Julian Harris | Atlanta | October 10, 1937 – January 8, 1938[1]:393 |

| Home in Glory | Clyde Limbaugh | Birmingham | April 16–May 15, 1936[1]:393 |

| It Can't Happen Here | Sinclair Lewis, John C. Moffitt | Seattle | October 27–November 6, 1936[1]:393 |

| Jericho | H. L. Fishel | Philadelphia + 3 | October 16, 1937 – April 4, 1938[1]:393 |

| John Henry | Frank Wells | Los Angeles | September 30–October 18, 1936[1]:393 |

| Lysistrata | Aristophanes, adapted by Theodore Browne | Seattle | September 17, 1936[1]:393 |

| Macbeth | William Shakespeare, adapted by Orson Welles | New York + 8 | April 14–October 17, 1936[1]:393 |

| The Natural Man | Theodore Browne | Seattle | January 28–February 20, 1937[1]:393 |

| The Swing Mikado | adapted from Gilbert and Sullivan | Chicago + 3 | September 25, 1938 – February 25, 1939[1]:393 |

| Return to Death | P. Washington Porter | Holyoke, Mass. | August 17–20, 1938[1]:393 |

| The Reverend Takes His Text | Ralf Coleman | Roxbury, Mass. + 3 | December 12, 1936[1]:393 |

| Romey and Julie | Robert Dunmore, Ruth Chorpenning | Chicago | April 1–25, 1936[1]:393 |

| Sweet Land | Conrad Seiler | New York | January 19–February 27, 1937[1]:393 |

| The Taming of the Shrew | William Shakespeare, adapted by project staff | Seattle | June 19–24, 1939[1]:393 |

| The Trial of Dr. Beck | Hughes Allison | New Jersey Spots + 2 | June 3–12, 1937[1]:393 |

| Trilogy in Black | Ward Courtney | Hartford | June 18, 1937[1]:393 |

| Turpentine | J. Augustus Smith, Peter Morell | New York | June 26–September 5, 1936[1]:393 |

| Unto Such Glory | Paul Green | New York | May 6–July 10, 1936[1]:393 |

| Walk Together Chillun | Frank H. Wilson | New York | February 4–March 7, 1936[1]:393 |

Standard drama productions

Numbers following the city of origin indicate the number of additional cities where the play was presented.

| Title | Author | City | Dates |

|---|---|---|---|

| Androcles and the Lion | George Bernard Shaw | Seattle + 2 | November 1–6, 1937[1]:428 |

| Bloodstream | Frederick Schlick | Boston | March 17–27, 1937[1]:428 |

| Bound East for Cardiff | Eugene O'Neill | New York | October 29, 1937 – January 15, 1938[1]:428 |

| Brother Mose | Frank Wilson | New York + 20 | July 25, 1934 – December 21, 1935[1]:428 |

| Cinda | H. J. Bates | Boston + 4 | January 21–24, 1936[1]:428 |

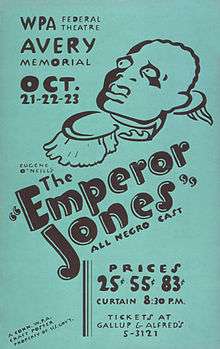

| The Emperor Jones | Eugene O'Neill | Hartford + 1 | October 21–23, 1937[1]:428 |

| The Field God | Paul Green | Hartford | February 17–19, 1938[1]:428 |

| Genesis | H. J. Bates, Charles Flato | Hyde Park, Mass. + 2 | February 26, 1936[1]:428 |

| Hymn to the Rising Sun | Paul Green | New York | May 6–July 10, 1937[1]:428 |

| In Abraham's Bosom | Paul Green | Seattle + 1 | April 21–May 22, 1937[1]:428 |

| In the Valley | Paul Green | Hartford | September 7–10, 1938[1]:428 |

| In the Zone | Eugene O'Neill | New York | October 29, 1937 – January 15, 1938[1]:428 |

| Just Ten Days | J. Aubrey Smith | New York | August 10–September 10, 1937[1]:428 |

| The Long Voyage Home | Eugene O'Neill | New York | October 29, 1937 – January 15, 1938[1]:428 |

| Mississippi Rainbow (Brain Sweat) | John Charles Brownell | Cleveland + 7 | April 18–May 10, 1936[1]:428 |

| The Moon of the Caribbees | Eugene O'Neill | New York | October 29, 1937 – January 15, 1938[1]:428 |

| Noah | André Obey | Seattle + 4 | April 28–July 8, 1936[1]:428 |

| Porgy | DuBose Heyward, Dorothy Heyward | Hartford | March 17–May 14, 1938[1]:428 |

| Roll, Sweet Chariot | Paul Green | New Orleans | June 16–18, 1936[1]:428 |

| Run, Little Chillun | Hall Johnson | Los Angeles + 2 | July 22, 1938 – June 10, 1939[1]:428 |

| The Sabine Women | Leonid Andreyev | Hartford | December 15–17, 1936[1]:429 |

| The Show-Off | George Kelly | Hartford | March 5–July 3, 1937[1]:429 |

| Stevedore | Paul Peters, George Sklar | Seattle | March 25–May 9, 1937[1]:429 |

| Swamp Mud | Harold Courlander | Birmingham | July 11, 1936[1]:429 |

| The World We Live In | Josef Čapek, Karel Čapek | Hartford | January 13–15, 1938[1]:429 |

Dance drama

New productions

Numbers following the city of origin indicate the number of additional cities where the play was presented.

| Title | Author | City | Dates |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adelante | Helen Tamiris | New York | April 20–May 6, 1939[1]:386 |

| All the Weary People | Project staff | Portland, Ore. | September 28, 1937[1]:386 |

| An American Exodus | Myra Kinch | Los Angeles + 1 | July 27, 1937 – January 4, 1939[1]:386 |

| Ballet Fedre | Berta Ochsner, Grace and Kurt Graff, Katherine Dunham | Chicago | January 27–February 19, 1938[1]:386 |

| Bonneville Dam | Project staff | Timberline Lodge, Ore. | September 29, 1937[1]:386 |

| Candide | Charles Weidman | New York | June 19–30, 1936[1]:386 |

| The Eternal Prodigal | Gluck-Sandor | New York | December 2, 1936 – January 2, 1937[1]:386 |

| Fantasy 1939 (Immediate Comment) | Berta Ochsner, David Campbell | New York | June 26–27, 1939[1]:386 |

| Federal Ballet | Ruth Page, Kurt Graff | Chicago + 5 | June 19–July 30, 1938[1]:386 |

| Federal Ballet (Guns and Castanets) | Ruth Page, Bentley Stone | Chicago + 1 | March 1–25, 1939[1]:386 |

| Folk Dances of All Nations | Lilly Mehlman | New York | December 27, 1937 – April 11, 1938[1]:386 |

| How Long Brethren | Helen Tamiris | New York + 1 | May 6, 1937 – January 15, 1938[1]:386 |

| Invitation to the Dance | Josef Castle | Tampa | July 18–22, 1937[1]:386 |

| Little Mermaid | Roger Pryor Dodge | New York | December 27, 1937 – April 11, 1938[1]:386 |

| El Maestro de Ballet | Senia Solomonoff | Tampa | July 18–22, 1937[1]:386 |

| Modern Dance Group | Project staff | Philadelphia | March 29, 1939[1]:386 |

| Mother Goose on Parade | Nadia Chilkovsky | New York | December 27, 1937 – April 11, 1938[1]:386 |

| Music in Fairyland | Myra Kinch | Los Angeles | December 25, 1937 – January 1, 1938[1]:386 |

| Prelude to Swing | Melvina Fried | Philadelphia | June 12–30, 1939[1]:386 |

| Salut au Monde | Helen Tamiris | New York | July 23–August 5, 1936–[1]:386 |

| Texas Flavor | B. Collie | Dallas | November 8–30, 1936[1]:387 |

| Trojan Incident | Euripides, adapted by Philip H. Davis | New York | April 21–May 21, 1938[1]:387 |

| With My Red Fires, To the Dance, The Race of Life | Doris Humphrey | New York | January 30–February 4, 1939[1]:387 |

| Young Tramps | Don Oscar Becque | New York | August 6–8, 1936[1]:387 |

Foreign-language drama

These plays were given their first professional production in the United States by the Federal Theatre Project. Titles are shown as they appeared on event programs. Numbers following the city of origin indicate the number of additional cities where the play was presented.

New productions

German

| Title | Author | City | Dates |

|---|---|---|---|

| Die Apostel | Rudolph Wittenberg | New York | April 15–20, 1936[1]:389 |

| Doktor Wespe | Roderich Benedix | New York | September 4–18, 1936[1]:389 |

| Einmal Mensch | Fritz Peter Buch | New York | December 3, 1936 – February 18, 1937[1]:389 |

| Seemanns-Ballade | Joachim Ringelnatz | New York | October 1–8, 1936[1]:386 |

Spanish

| Title | Author | City | Dates |

|---|---|---|---|

| Esto No Pasará Aqui | Sinclair Lewis, John C. Moffitt | Tampa | October 27–November 1, 1936[1]:389 |

Yiddish

| Title | Author | City | Dates |

|---|---|---|---|

| Awake and Sing | Clifford Odets, adapted by Chaver Paver | New York + 1 | December 22, 1938 – April 9, 1939[1]:389 |

| Awake and Sing | Clifford Odets, adapted by Sigmund Largman | Los Angeles | April 1, 1937 – April 11, 1938[1]:389 |

| It Can't Happen Here | Sinclair Lewis, John C. Moffitt | Los Angeles New York Paterson, N. J. |

October 27–November 3, 1936[1]:389 October 27, 1936 – May 1, 1937[1]:389 April 18–19, 1937[1]:389 |

| Monesh | I. L. Peretz, adapted by Jonah Spivak | Chicago | September 7–November 14, 1937[1]:389 |

| Professor Mamlock | Friedrich Wolf | Peabody, Mass. + 3 | February 10, 1938[1]:389 |

| The Tailor Becomes a Storekeeper | David Pinski | Chicago + 1 | February 25–April 9, 1938[1]:389 |

| Uptown and Downtown | Boris Thomashefsky and Cornblatt | New York | January 1, 1935 – June 17, 1936[1]:389 |

| We Live and Laugh | Project staff | New York | June 9, 1936 – March 5, 1937[1]:389 |

Radio

The Federal Theatre of the Air began weekly broadcasts March 15, 1936. For three years the radio division of the Federal Theatre Project presented an average of 3,000 programs annually on commercial stations and the NBC, Mutual and CBS networks. The major programs originated in New York; radio divisions were also created in 11 states.[1]:267–268, 397

Series included Professional Parade, hosted by Fred Niblo; Experiments in Symphonic Drama, original stories written for classical music; Gilbert and Sullivan Light Opera, the complete works performed by Federal Theatre actors and recordings by D'Oyly Carte; Ibsen's Plays, performances of 12 major plays; Repertory Theatre of the Air, presenting literary classics; Contemporary Theatre, presenting plays by modern authors; and the interview program, Exploring the Arts and Sciences.[1]:268

The radio division presented a wide range of programs on health and safety, art, music and history. The American Legion sponsored James Truslow Adams's Epic of America. The children's program, Once Upon a Time, and Paul de Kruif's Men Against Death were both honored by the National Committee for Education by Radio. In March 1939, at the invitation of the BBC, Flanagan broadcast the story of the Federal Theatre Project to Britain. Asked to expand the program to encompass the entire WPA, the radio division produced No Help Wanted, a dramatization by William N. Robson with music by Leith Stevens. The Times called it "the best broadcast ever sent us from the Americas".[1]:268–269[8]

Productions criticized by Congress

A total of 81 of the Federal Theatre Project's 830 major titles were criticized by members of Congress for their content in public statements, committee hearings, on the floor of the Senate or House, or in testimony before Congressional committees. Only 29 were original productions of the Federal Theatre Project. The others included 32 revivals or stock productions; seven plays that were initiated by community groups; five that were never produced by the project; two works of Americana; two classics; one children's play; one Italian translation; and one Yiddish play.[1]:432–433

The Living Newspapers that drew criticism were Injunction Granted, a history of American labor relations; One-Third of a Nation, about housing conditions in New York; Power,[1]:433 about energy from the consumer's point of view;[1]:184–185 and Triple A Plowed Under, on farming problems in America.[1]:433 Another that was criticized, on the history of medicine, was not completed.[1]:434

Dramas criticized by Congress were American Holiday, about a small-town murder trial; Around the Corner, a Depression-era comedy; Chalk Dust, about an urban high school; Class of '29, the Depression years as seen through young college graduates; Created Equal, a review of American life since colonial times; It Can't Happen Here, Sinclair Lewis's parable of democracy and dictatorship; No More Peace, Ernst Toller's satire on dictatorships; Professor Mamlock, about Nazi persecution of Jews; Prologue to Glory, about the early life of Abraham Lincoln; The Sun and I, about Joseph in Egypt; and Woman of Destiny, about a female President who works for peace.[1]:433

Negro Theatre Unit productions that drew criticism were The Case of Philip Lawrence, a portrait of life in Harlem; Did Adam Sin?, a review of black folklore with music; and Haiti, a play about Toussaint Louverture.[1]:433

Also criticized for their content were the dance dramas Candide, from Voltaire; How Long Brethren, featuring songs by future Guggenheim Fellowship recipient Lawrence Gellert; and Trojan Incident, a translation of Euripides with a prologue from Homer.[1]:433

Help Yourself, a satire on high-pressure business tactics, was among the comedies criticized by Congress. Others were Machine Age, about mass production; On the Rocks by George Bernard Shaw; and The Tailor Becomes a Storekeeper.[1]:433

Children's plays singled out were Mother Goose Goes to Town, and Revolt of the Beavers, which the New York American called a "pleasing fantasy for children".[1]:433

The musical Sing for Your Supper also met with Congressional criticism, although its patriotic finale, "Ballad for Americans", was chosen as the theme song of the 1940 Republican National Convention.[1]:433

Cultural references

A fictionalized view of the Federal Theatre Project is presented in the 1999 film Cradle Will Rock, in which Cherry Jones portrays Hallie Flanagan.[9]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 87 88 89 90 91 92 93 94 95 96 97 98 99 100 101 102 103 104 105 106 107 108 109 110 111 112 113 114 115 116 117 118 119 120 121 122 123 124 125 126 127 128 129 130 131 132 133 134 135 136 137 Flanagan, Hallie (1965). Arena: The History of the Federal Theatre. New York: Benjamin Blom, reprint edition [1940]. OCLC 855945294.

- ↑ Roosevelt, Franklin D. (August 26, 1935). "Letter on Allocation of Work Relief Funds". The American Presidency Project. Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley. Retrieved 2015-03-04.

- 1 2 3 4 Ross, Ronald (January 1974). "The Role of Blacks in the Federal Theatre, 1935–1939". The Journal of Negro History. 59 (1): 38–50. JSTOR 2717139.

- ↑ Flanagan, Hallie (October 24, 1935). "Instructions for Federal Theatre Projects of the Works Progress Administration". New Deal Stage. Library of Congress. Retrieved 2015-03-08.

- 1 2 Houseman, John (1972). Run-Through: A Memoir. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-671-21034-3.

- ↑ Dunning, Jennifer (July 5, 1981). "'New Deal' Artists Star in a TV Documentary". The New York Times. Retrieved 2015-02-27.

- 1 2 Hill, Anthony D. (2009). The A to Z of African American Theater. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group. ISBN 9780810870611.

- ↑ "No Help Wanted". RadioGOLDINdex. Retrieved 2015-03-31.

- ↑ Maslin, Janet (December 8, 1999). "Cradle Will Rock (1999): Panoramic Passions On a Playbill From the 30's". The New York Times. Retrieved 2015-03-02.

Further reading

- Batiste, Stephanie Leigh. Darkening Mirrors: Imperial Representation in Depression-Era African American Performance (Duke University Press; 2012) 352 pages; Explores African-Americans' participation on stage and screen; especially FTP's "voodoo" Macbeth.

- Newton, Christopher. "In Order to Obtain the Desired Effect": Italian Language Theater Sponsored by the Federal Theatre Project in Boston, 1935–39," Italian Americana, (Sep 1994) 12#2 pp 187–200.

- Osborne, Elizabeth A. Staging the People: Community and Identity in the Federal Theatre Project. New York: Palgrave, 2011.

- Quinn, Susan. Furious Improvisation: How the WPA and a Cast of Thousands Made High Art Out of Desperate Times. New York: Walker and Company, 2008.

- Schwartz, Bonnie Nelson. Voices from the Federal Theatre. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2003.

- Witham, Barry B. The Federal Theatre Project: A Case Study (2004).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Federal Theatre Project. |

- Library of Congress

- Billy Rose Theatre Division, New York Public Library for the Performing Arts

- Federal Theatre Project Materials Collection at George Mason University

- Federal Theatre Project Collection, 1936–1939, CTC.1979.02, Curtis Theatre Collection, Special Collections Department, University of Pittsburgh

- BlackPast.org: Federal Theatre Project (Negro Units)

- "An Hour Upon the Stage: The Brief Life of Federal Theatre". Humanities: The Magazine of the National Endowment for the Humanities, July/August 2003

- American Studies at the University of Virginia: Triple A Plowed Under — full text plus recreation-for-radio production of the Federal Theater Project drama.

- Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture — Federal Theater Project

- "Federal Theater Project in Washington State", by Sarah Guthu — from the Great Depression in Washington State Project