William Smellie (obstetrician)

| William Smellie | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

5 February 1697 Lanark, Scotland |

| Died |

5 March 1763 Lanark, Scotland |

| Nationality | Scottish |

| Fields | Obstetrics, Anatomy |

| Alma mater | University of Glasgow |

William Smellie (5 February 1697, Lanark – 5 March 1763, Lanark) was a Scottish obstetrician who practiced and taught primarily in London .[1] He is notable as one of the first prominent male midwives in Britain. Through his work, he established safer delivery practices and helped make obstetrics more scientifically based.[2]

Life

Smellie was born on 5 February 1697 in the town of Lanark, Scotland. He practiced medicine before getting a license, opening an apothecary in 1720 in Lanark. It was not a particularly lucrative venture, as also sold cloth as a side business to supplement his income, but he began reading medical books and teaching himself obstetrics at this time. By 1728, he was married to Eupham Borland, who was seven years his senior.[2] He enrolled later at the University of Glasgow and received his M.D. degree in 1745. After training in obstetrics in London and Paris, he opened a practice in London and began teaching. This practice proved far more successful than his first one, and Smellie made a name for himself in London (much to the surprise of friends from his hometown).[2]

Smellie's work helped make obstetrics much more scientifically-based.[3] He invented a "machine", an obstetrical manikin, for instructing his students. It essentially functioned as a model of the birthing process, and would nowadays be referred to as a "phantom". While not an original idea, the phantom was far more accurate than previous models and allowed him to visually demonstrate midwifing techniques.[2] He also designed an improved version of the obstetrical forceps, which had been recently revealed after the midwifing Chamberlen family had kept it secret for generations.[2] He publicized the use of these instruments although promoted natural birth as the best method of delivery due to its less invasive nature. In his new version, Smellie shortened and curved the blades and included a locking mechanism.[3] In addition, he described the mechanism of labour, devised a maneuver to deliver the head of a breech, and published his teachings. He was the first observer and recorder of the natural birthing process and detailed the method by which the head of the child exited the female pelvis.[4] Smellie also challenged the commonly accepted concept of saving the mother over the child in times of complication. Through the introduction of forceps in the field of obstetrics, more delicate maneuvers could be performed and therefore obstetricians were able to equally weigh the life of the mother and child when complications did arise and were more often able to resolve the problem and save both. He was the first recorded figure to be able to resuscitate an infant after lung collapse and describe in detail uterine dystocia.[5]

Smellie was highly respected as not just a midwife but a teacher. Ten years after establishing his London practice, Smellie had 900 pupils and 200 lecture courses. His students did not gain any certification or fulfill medical training requirements by attending his courses, but came seeking to enhance their knowledge[2] As a teacher, Smellie tried to provide his students with live demonstrations to go along with course lectures. Consequently, he offered free midwifing services to patients if they allowed his students to observe the birthing process. This led to a more general practice of medical students attending parturition as a part of their medical training.[6] One of his students, William Hunter, went on to become a well-known obstetrician as well and served as the official midwife of Queen Charlotte, wife of King George III. Unlike William Hunter, William Smellie was able to gain prestige and success without connections to highly reputable individuals in society. Through his humble background, Smellie was able to gain great acclaim through his deep interest in the field of obstetrics and is now seen as a pioneer in not only OBGYN but also an innovator of medical tools and reference literature.

His work was not without opposition though. At the time, midwifery was a female-dominated profession. Most female midwives argued that it was inappropriate for men to assist women with childbirth, and many patients agreed. However, Smellie's work helped begin the shift of obstetrics from the work of women with some degree of experience to a medical field practiced largely by trained male physicians and surgeons.[2]

He taught and midwifed until 1759, in which year he retired and returned to his hometown Lanark. He passed his practice on to Dr. John Harvie, who had married Smellie's niece. In retirement, Smellie focused on compiling and refining his findings into books, including the last volume of A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Midwifery" . He died at the age of 66 on 5 March 1763, in time to finish his book but not to see it published.[2]

In 1828, John Harvie donated a portrait of William Smellie to the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh. Smellie most likely painted this portrait himself in 1719.[2]

Books

A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Midwifery (published in three volumes from 1752–64) describes the mechanism of labour and how to handle the normal birthing process along with various complications that might arise.[3] Furthermore, the book was the first to set up procedures for ensuring the safe use of obstetrical forceps, as Smellie recognized that the forceps were a life-saving tool but best used sparingly.[6] By the time Smellie published the first volume book, he had been practicing for over 30 years and was involved in around 1,150 deliveries. The information presented in his book was illuminating, as few people at the time had so much experience in midwifing.[2]

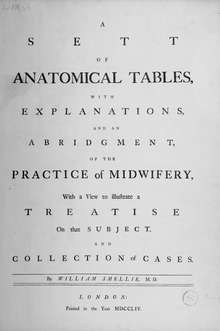

A Sett of Anatomical Tables (1754) was also an important contribution to the field of obstetrics. This was a compilation of his anatomical drawings depicting childbirth and pregnancy. Though only one hundred copies were made, it was groundbreaking in its detail and anatomical accuracy.[3]

Controversy

Modern historical analysis from the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine has come to question William Smellie’s practice of obstetrics and the methods by which he performed his research. Through modern analysis, historians have come to believe that William Smellie and his collaborator and later competitor William Hunter were the cause of several dozen murders of pregnant women in order to gain access to corpses for anatomical dissection and physiological experimentation. Due to the inadequate match between supply and demand of corpses, scientists had to find other means, often requiring illegal methods, to obtain access. The process was named "burking" after the anatomist William Burke who performed or commissioned several dozen murders in the name of scientific experimentation.[7] Oftentimes, grave robbing was also not a sufficient method by which obstetricians could access the specific type of tissue required for testing and dissection. There are varied hypothesis on what was the primary motivation behind the supposed mass killings. Historians hypothesize that one of the driving forces was the rivalry between William Smellie and William Hunter and their desire to be the leading researcher and physician on the field of obstetrics. Both physicians worked to understand the mechanisms of cesarean sections and reviving unborn fetuses after the pregnant woman has died. William Smellie is often hailed as the "father of British midwifery" by many historians. Although he has been viewed as a major figure in propelling the field of obstetrics, he also received much back-lash against his work during his time. In 1755, there was much fervor and questioning of Smellie’s access to these corpses. Many of the accusations came from competitors, and fearing trial and even execution, Smellie stopped his work for several years in an effort to quench the suspicion that had been raised.[7]

Legacy

The tomb in which William Smellie (and later his wife) was buried still stands in the St. Kentigerns section of the state run Lanark graveyard. The William Smellie Memorial Hospital which provided maternity services in Lanark closed in the early 1990s and was re-located to a unit at the Law Hospital in Carluke. This was also subsequently closed and maternity services moved to Wishaw General Hospital.

References

- ↑

"Smellie, William (1697-1763)". Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

"Smellie, William (1697-1763)". Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900. - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Smellie, William (1876). Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Midwifery. Ed. with annotations, by Alfred H. McClintock. London: The New Syndenham Society. pp. 1–23. ISBN 9780882751597.

- 1 2 3 4 "William Smellie". Vaulted Treasures: Historical Medical Books at the Claude Moore Health Sciences. 2007. Retrieved 9 March 2017.

- ↑ Campbell, Dennis (February 6, 2010). "Founders of British obstetrics 'were callous murderers'". The Guardian.

- ↑ Dunn, P.M. (January 1995). "Dr William Smellie (1697-1763), the master of British midwifery.". NIH. 72: F77–8. PMC 2528415

. PMID 7743291. doi:10.1136/fn.72.1.f77.

. PMID 7743291. doi:10.1136/fn.72.1.f77. - 1 2 "Medicine in the 18th Century". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 3 March 2017.

- 1 2 Encyclopedia Wikipedia Editors (December 7, 2012). "William Smellie".

- Speert, H (1958). Essays in Eponymy: Obstetric and Gynecologic Milestones. Macmillan.

- Lanark Museum

External links

- William Smellie: A sett of anatomical tables, with explanations, and an abridgment, of the practice of midwifery (London, 1754)]. Selected pages scanned from the original work. Historical Anatomies on the Web. US National Library of Medicine.

Media related to William Smellie (obstetrician) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to William Smellie (obstetrician) at Wikimedia Commons