W.E.B. Du Bois Boyhood Homesite

|

W.E.B. Du Bois Boyhood Homesite | |

Memorial boulder, 2010 | |

| |

| Location | Great Barrington, Massachusetts |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 42°10′42″N 73°23′37″W / 42.17833°N 73.39361°WCoordinates: 42°10′42″N 73°23′37″W / 42.17833°N 73.39361°W |

| Area | 5 acres (2.0 ha)[1] |

| Architect | Unknown |

| NRHP Reference # | [2] |

| Added to NRHP | May 11, 1976 |

The W.E.B. Du Bois Boyhood Homesite (or W.E.B. Du Bois Homesite) is a National Historic Landmark in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, commemorating an important location in the life of African American intellectual and civil rights activist W.E.B. Du Bois (1868–1963). The site contains foundational remnants of the home of Du Bois' grandfather, where Du Bois lived for the first five years of his life. Du Bois was given the house in 1928, and planned to renovate it, but was unable to do so. He sold it in 1954 and the house was torn down later that decade. The site is located on South Egremont Road (state routes 23 and 41), west of the junction with Route 71.

Plans to develop the site as a memorial to Du Bois in the late 1960s were delayed due to local opposition. The site's proponents attributed this in part to racism, but opinions were generally expressed as opposition to Du Bois' more radical politics in later life. On May 11, 1976 the site was declared a National Historic Landmark and listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The site was donated to the state in 1987, and is administered by the University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

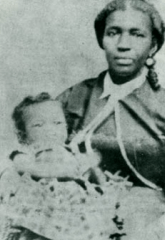

History

The Burghardt family (of Dutch origin) was present in the vicinity of Great Barrington, Massachusetts in colonial times, with documented ownership of land in the area from the 1740s. Tom Burghardt, an African-American slave of the family with Dutch, English, African and Native American ancestry, probably earned his freedom for his participation in the American Revolutionary War.[3] One of his descendants was Mary Silvinia Burghardt, the mother of William Edward Burghardt Du Bois (commonly referred to as W.E.B. Du Bois), born in 1868. He became a leading African American intellectual, civil rights activist, and co-founder of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).[1]

By the early 19th century, the "Black Burghardts" had settled in the Egremont Plain area a few miles outside the center of Great Barrington.[4] Du Bois' birthplace was torn down around 1900).[5] When abandoned by Du Bois' father, his mother moved with her infant son to the house of her parents, Othello Burghardt and his wife.[6] In his 1928 article, "The House of the Black Burghardts", Du Bois described the house as "a delectable place — simple, square and low, with the great room of the fireplace, the flagged kitchen, half a step below, and the lower woodshed beyond. Steep strong stairs led to Sleep, while without was a brook, a well and a mighty elm."[7]

When Du Bois was five years old, his grandfather died, and his grandmother was forced to sell her house to settle debts.[8] Du Bois' mother moved the family into Great Barrington, where she struggled to support her son. A gifted student, Du Bois attended Fisk University on scholarship and with funds raised by members of his First Congregational Church in town. He completed a second bachelor's degree at Harvard, as well as graduate work there and in Berlin, becoming the first African American to earn a doctorate at Harvard. He embarked on a distinguished career.[1] Over the next decades, Du Bois periodically returned to Great Barrington. His children were born there (in the homes of maternal relatives). He buried his son Burghardt (1887–89) and wife Nina (d. 1950) there. In 1906, he sent his young family to Great Barrington from where he was working in Atlanta, Georgia, after that year's race riots.[9]

Dubois expressed interest in purchasing his grandfather's property on a visit to Great Barrington in 1925.[10] Three years later the brothers Joel and Arthur Spingarn, both civil rights activists involved in the NAACP, raised funds and purchased the old Burghardt homestead as a gift to Du Bois for his sixtieth birthday.[11] Du Bois had plans to transform the property into a middle-class summer retreat, but financial difficulties and his move in 1934 from New York City to Atlanta made it too difficult to accomplish that. Du Bois finally sold the property to a neighbor in 1954, who had the house (by then dilapidated) torn down.[12]

Conversion to memorial

In 1967 Walter Wilson and Edmund W. Gordon purchased two parcels of the old Burghardt lands, including the site of the Burghardt house, that form a U shape around a private residence,[1][7] and announced the intention of converting the property into a park to commemorate Du Bois. This plan met with local opposition. Wilson and Gordon were both outsiders: Wilson was a controversial area real estate developer originally from Tennessee, and Gordon was from New York City.[13]

Opposition was generally couched as criticism of Du Bois for his Communist sympathies and his renunciation of American citizenship for that of Ghana late in life. He died and was buried there. This was a period in the United States of growing controversy related to the Vietnam War and tumultuous social changes, and Du Bois' position was resented by veterans' organizations such as the Veterans of Foreign Wars.[14] Wilson worked to explain Du Bois' complex legacy and support for civil rights. He noted that Benedict Arnold was memorialized at Saratoga for his role in the 1777 Battles of Saratoga despite his later treason during the Revolution.[15] Some supporters of the memorial suspected the FBI was behind the opposition (Du Bois having been under its scrutiny because of his Communist views). The FBI was found to have considered planting a critical news story, but it concluded that local opposition was sufficient and did not intervene.[16] Wilson felt that many opponents were motivated by racial issues, although no opposition was expressed in racial terms. This was a period in which the Civil Rights Movement had captured national attention, court decisions, and legislation that resulted in major changes.[17]

Wilson and Gordon established the Du Bois Memorial Foundation to take ownership of the property. Funded in part by high-profile donors including Ruby Dee, Ossie Davis, Sidney Poitier, and Norman Rockwell, the foundation received the property in September 1969 and dedicated it to Du Bois later that year.[7][18] Local hostility continued; the Berkshire Courier, while counseling against violence, suggested the site be vandalized.[19] The town briefly threatened to prevent the dedication ceremony, suggesting there was a question as to whether the intended use of the site met local zoning regulations.[20]

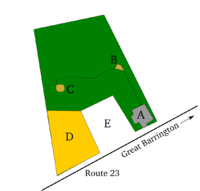

- *A: Parking lot

- *B: Interpretive display

- *C: Commemorative boulder

- *D: Home site area

- *E: Private property

Over the next ten years, the Foundation did not develop the property in any significant way. Its members were reluctant to place permanent markers and displays on it for fear of vandalism or theft.[21] In 1976, a decade after Du Bois' death, the site was designated a National Historic Landmark, and listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[2] In 1983 the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, with the permission of the Foundation, began a series of archaeological excavations on the property, seeking to research the history of the "Black Burghardt" family. It already had amassed a collection of Du Bois papers.[22] In 1987 the Foundation turned the property over to the state, with the university as its steward. The university paid for the construction of a parking area and the installation of interpretive signs.[7]

Today

Since the late 20th century, the two parcels of land that form the 5-acre (2.0 ha) site have been planted with a thick grove of pine trees. A path leads north from the parking area to an informational kiosk about Du Bois and his life. From there another path leads west, into a small depression where a memorial boulder was installed with a commemorative plaque. Near the southwest corner of the property are the remnants of the original house's stone foundation.[1] Although Great Barrington residents have come to support the Du Bois legacy and have marked other places in town important in his life, the site has been the occasional target of vandalism. But this happens in many public places.[23] The site is considered part of the Upper Housatonic Valley National Heritage Area.[7]

— W.E.B. Du Bois[24]

See also

- List of National Historic Landmarks in Massachusetts

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Berkshire County, Massachusetts

- African-American historic places

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 Graves, Lynn Gomez (October 30, 1975). "National Register of Historic Places nomination, W.E.B. Du Bois Boyhood Home Site" (PDF). National Park Service. Retrieved 2013-05-29.

- 1 2 National Park Service (2008-04-15). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- ↑ Lewis, p. 13

- ↑ Glassberg and Paynter, p. 243

- ↑ Lewis, p. 21

- ↑ Wolters, pp. 6–8

- 1 2 3 4 5 "W.E.B. Du Bois Boyhood Homesite and Great Barrington: A Plan for Heritage Conservation and Interpretation" (PDF). Friends of the W.E.B. Du Bois Homesite. Retrieved 2013-05-29.

- ↑ Lewis, pp. 22–23

- ↑ Bass, pp. 25–26

- ↑ Drew, p. 3

- ↑ Lewis, p. 493

- ↑ Glassberg and Paynter, p. 245

- ↑ Bass, p. 58

- ↑ Bass, pp. 60–63

- ↑ Bass, pp. 71–72

- ↑ Bass, pp. 122–123

- ↑ Bass, pp. 74–75

- ↑ Bass, pp. 88–90

- ↑ Glassberg and Paynter, p. 246

- ↑ Bass, p. 88

- ↑ Bass, pp. 132–133

- ↑ Glassberg and Paynter, p. 249

- ↑ Glassberg and Paynter, pp. 250–252

- ↑ Bass, p. 5

References

- Bass, Amy (2009). Those About Him Remained Silent: The Battle Over W.E.B. Du Bois. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 9780816644957. OCLC 351318474.

- Drew, Bernard (Winter 2012). "Have I got a building lot for you! Warren Davis said" (PDF). Newsletter of the Friends of W.E.B. Du Bois Homesite. W.E.B. Du Bois Homesite (5).

- Glassberg, David; Paynter, Robert (2012). "Du Bois in Great Barrington". Born in the U.S.A.: Birth, Commemoration, and American Public Memory. University of Massachusetts Press. ISBN 9781558499386. OCLC 768167097.

- Lewis, David (2009). W.E.B. Du Bois: A Biography. New York: Henry Holt. ISBN 9780805087697. OCLC 176972569.

- Wolters, Raymond (2004). Du Bois and his Rivals. Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press. ISBN 9780826215192. OCLC 176796914.

Further reading

- Paynter, Robert (2014). "Building an Historical Landscape, Commemorating W.E.B. Du Bois". International Journal of Historical Archaeology. 18: 316–39.

External links

- Official website

- Website of Friends of the W. E. B. Du Bois Homesite

- UMass Archaeological survey of the site