Votic language

| Votic | |

|---|---|

| Vod | |

| vađđa ceeli, maaceeli | |

| Native to | Russia |

| Region | Ingria |

| Ethnicity | Votes |

Native speakers | 68 (2010 census)[1] |

| Dialects | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-2 |

vot |

| ISO 639-3 |

vot – inclusive codeIndividual code: zkv – Krevinian |

| Glottolog |

voti1245[2] |

Votic or Votian (vađđa ceeli or maaceeli; also written vaďďa tšeeli, maatšeeli in old orthography[3]) is the language spoken by the Votes of Ingria, belonging to the Finnic branch of the Uralic languages. Votic is spoken only in Krakolye and Luzhitsy, two villages in Kingiseppsky District, and is close to extinction. In 1989 there were 62 speakers left, the youngest born in 1938. In its 24 December 2005 issue, The Economist wrote that there are only approximately 20 speakers left.[4]

History

Votic is one of numerous Finnic varieties known from Ingria, and generally considered the oldest of these. Votic shares some similarities with and has acquired loanwords from the adjacent Ingrian language, but also has deep-reaching similarities with Estonian to the west, which is considered its closest relative. Some linguists including Tiit-Rein Viitso and Paul Alvre[5] have claimed that Votic evolved specifically from northeastern dialects of ancient Estonian.[6] Votic regardless exhibits several features that indicate its distinction from Estonian (both innovations such as the palatalisation of velar consonants and a more developed system of cases, and retentions such as vowel harmony). According to Estonian linguist Paul Ariste, Votic was distinct from other Finnic languages, such as Finnish and Estonian, as early as the 6th century AD and has evolved independently ever since.

Isoglosses setting Votic apart from the other Finnic languages include:

- Loss of initial *h

- Palatalization of *k to /tʃ/ before front vowels. This was a relatively late innovation, not found in Kreevin Votic or Kukkuzi Votic.

- Lenition of the clusters *ps, *ks to /hs/

- Lenition of the cluster *st to geminate /sː/

Features shared with Estonian and the other southern Finnic languages include:

- Loss of word-final *n

- Shortening of vowels before *h

- Introduction of /ɤ/ from backing of *e before a back vowel

- Development of *o to /ɤ/ in certain words (particularly frequent in Votic)

- Loss of /h/ after a sonorant (clusters *lh *nh *rh)

In the 19th century Votic was already declining in favour of Russian (there were around 1,000 speakers of the language by the start of the World War I). After the Bolshevik Revolution, under Lenin, Votic had a brief revival period, with the language being taught at local schools and the first-ever grammar of Votic (Jõgõperä/Krakolye dialect) being published. But after Joseph Stalin came into power, the language began to decline. World War II had a devastating effect on the Votic language, with the number of speakers considerably decreased as a result of military offensives, deliberate destruction of villages by Nazi troops, forced migration to the Klooga concentration camp in Estonia and to Finland under the Nazi government, and the Stalinist policy of "dispersion" immediately after the war against the families whose members had been sent to Finland under the Nazi government. Since then, the Votes have largely concealed their Votic identity, pretending to be Russians in the predominantly Russian environment. But they continued to use the language at home and when talking to family members and relatives. After the death of Stalin, the Votes were no longer mistreated and many of those who had been sent away returned to their villages. But the language had considerably declined and the number of bilingual speakers increased. Because Votic was stigmatised as a language of "uneducated villagers", Votic speakers avoided using it in public and Votic children were discouraged from using it even at home because, in the opinion of some local school teachers, it prevented them from learning to speak and write in Russian properly. Thus, in the second half of the 20th century there emerged a generation of young ethnic Votes whose first language was Russian and who understood Votic but were unable to speak it.

Dialects

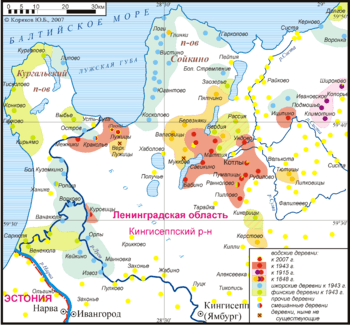

Three definite dialect groups of Votic are known:

- Western, the areas around the mouth of the Luga River

- Eastern, in villages around Koporye

- Krevinian, areas around the city of Bauska, Latvia

The Western dialect area can be further divided into the Central dialects (spoken around the village of Kattila) and the Lower Luga dialects.[7]

Of these, only the Lower Luga dialect is still spoken.

In 1848 it was estimated that of a total of 5,298 speakers of Votic, 3,453 (65%) spoke the western dialect, 1,695 (35%) spoke the eastern and 150 (3%) spoke the dialect of Kukkuzi. Kreevin had 12-15 speakers in 1810, the last records of Kreevin speakers are from 1846. The Kreevin dialect was spoken in an enclave in Latvia by descendants of Votic prisoners of war who were brought to the Bauska area of Latvia in the 15th century by the Teutonic order.[8] The last known speaker of the eastern dialect died in 1960, in the village of Icäpäivä (Itsipino).[9]

A fourth dialect of Votic has often been claimed as well: the traditional language variety of the village of Kukkuzi. It shows a mix of features of Votic and neighboring Ingrian, and some linguists have claimed that it is actually rather a dialect of Ingrian.[10] The vocabulary and phonology of the dialect are largely Ingrian-based, but it shares some grammatical features with the main Votic dialects, probably representing a former Votic substratum.[7] In particular, all phonological features that Votic shares specifically with Estonian (e.g. the presence of the vowel õ) are absent from the dialect.[11] The Kukkuzi dialect has been declared to be extinct since the 1970s,[9] although three speakers have still been located in 2006.[7]

Orthography

In the 1920s, the Votic linguist Dmitri Tsvetkov wrote a Votic grammar using a modified Cyrillic alphabet. The current Votic alphabet was created by Mehmet Muslimov in 2004:[12]

| A а | Ä ä | B b | C c | D d | D' d' | E e | F f | G g |

| H h | I i | J j | K k | L l | L' l' | M m | N n | N' n' |

| O o | Ö ö | Õ õ | P p | R r | R' r' | S s | S' s' | Š š |

| Z z | Z' z' | Ž ž | T t | T' t' | U u | V v | Ü ü | Ts ts |

In linguistic works, one may find different transcriptions of Votic. Some use a modified Cyrillic alphabet, and some Latin. The transcriptions based on Latin have many similarities with closely related Finnic languages, such as the use of č for /t͡ʃ/. At least a couple of ways exist for indicating long vowels in Votic; placing a macron over the vowel (such as ā), or as in written Estonian and Finnish, doubling the vowel (aa). Geminate consonants are generally represented with two characters. The representation of central vowels varies. In some cases the practice is to use e̮ according to the standards of Uralic transcription, while in other cases the letter õ is used, as in Estonian.

Phonetics and phonology

Vowels

Votic has 10 vowels, which are loosely represented by the following chart. The Votic õ, however, is known to be a bit higher than the Estonian õ, but the rest of the vowels generally correspond to Estonian.

| (IPA) (FUT) | Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| unrounded | rounded | |||

| Close | /i/ i | /y/ ü | /ɨ/ i̮ | /u/ u |

| Close-mid | /e/ e | /ø/ ö | /ɤ/ õ | /o/ o |

| Open | /æ/ ä | /ɑ/ a | ||

All of the vowels may occur short or long, however in some central dialects the long mid vowels /eː oː øː/ have been diphthongized to /ie uo yø/. Thus, tee 'road' is pronounced as tie. Votic also has a large inventory of diphthongs.

Votic has a system of vowel harmony, rather similar to Finnish in its overall behavior: the vowels are divided in three groups, front-harmonic, back-harmonic and neutral. Words may generally not contain both front-harmonic and back-harmonic vowels; but both groups can combine with neutral vowels. The front-harmonic vowels are ä e ö ü; the corresponding back-harmonic vowels are a õ o u. Unlike Finnish, Votic only has a single neutral vowel, i.

However, there are some exceptions with the behavior of o ö. Some suffixes including the vowel o do not harmonize (the occurrence of ö in non-initial syllables is generally a result of Finnish or Ingrian loan words), and similarly onomatopoetic words and loanwords are not necessarily subject to rules of vowel harmony.

Consonants

| Labial | Dental | Postalveolar | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | pal. | |||||||

| Nasal | m | n | nʲ | ŋ | ||||

| Plosive | voiceless | p | t | tʲ | k | |||

| voiced | b | d | dʲ | ɡ | ||||

| Affricate | voiceless | ts | (tsʲ) | tʃ | ||||

| voiced | (dʒ) | |||||||

| Fricative | voiceless | f | s | sʲ | ʃ | x | h | |

| voiced | v | z | zʲ | ʒ | ʝ | |||

| Trill | r | rʲ | ||||||

| Lateral approximant | l | lʲ | ||||||

Notes:

- /dʒ/ occurs only in eastern Votic, as a weak-grade counterpart to /tʃ/.

- Palatalised consonants are rare and normally allophonic, occurring automatically before /i/ or before a consonant that in turn is followed by /i/. Phonemic palatalised consonants occur mostly as the result of a former following /j/, usually as geminates. In other environments they are almost entirely found in loanwords, primarily from Russian. In some words in certain dialects, a palatalised consonant may become phonemic by the loss of the following vowel, such as esimein > eśmein.

- /tʲ/ is affricated to [tsʲ] in Kukkuzi Votic.

Nearly all Votic consonants may occur as geminates. Also, Votic also has a system of consonant gradation, which is discussed in further detail in the consonant gradation article, although a large amount of alternations involve voicing alternations. Two important differences in Votic phonetics as compared to Estonian and Finnish is that the sounds /ʝ/ and /v/ are actually fully fricatives, unlike Estonian and Finnish, in which they are approximants. Also, one possible allophone of /h/ is [ɸ], ühsi is thus pronounced as IPA: [yɸsi].

The lateral /l/ has a velarized allophone [ɫ] when occurring adjacent to back vowels.

Voicing is not contrastive word-finally. Instead a type of sandhi occurs: voiceless [p t k s] are realized before words beginning with a voiceless consonant, voiced [b d ɡ z] before voiced consonants (or vowels). Before a pause, the realization is voiceless lenis, [b̥ d̥ ɡ̊ z̥]; the stops are here similar to the Estonian b d g. Thus:

- pre-pausal: [vɑrɡɑz̥] "thief"

- before a voiceless consonant: [vɑrɡɑs‿t̪uɤb̥] "a thief comes"

- before a voiced consonant: [vɑrɡɑz‿vɤt̪ɑb̥] "a thief takes"

Grammar

Votic is an agglutinating language much like the other Finnic languages. In terms of inflection on nouns, Votic has two numbers (singular, plural), and 16 cases: nominative, genitive, accusative (distinct for pronouns), partitive, illative, inessive, elative, allative, adessive, ablative, translative, essive, exessive, abessive, comitative, terminative.

Unlike Livonian, which has been influenced to a great extent by Latvian, Votic retained its Finnic characteristics. There are many loan words from Russian, but not a phonological and grammatical influence comparable with the Latvian influence to Livonian.

In terms of verbs, Votic has six tenses and aspects, two of which are basic: present, imperfect; and the rest of which are compound tenses: present perfect, past perfect, future and future perfect. Votic has three moods (conditional, imperative, potential), and two 'voices' (active and passive). Caution however should be used with the term 'passive', with Finnic languages though as a result of the fact that it is more active and 'impersonal' (it has an oblique 3rd person marker, and so is not really 'passive').

References

- ↑ Votic at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015)

Krevinian at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) - ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin; Bank, Sebastian, eds. (2016). "Votic". Glottolog 2.7. Jena: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- ↑ V. Černiavskij. "Vaďďa tšeeli (Izeõpõttaja) / Водский язык (Самоучитель) ("Votic Self-Taught Book")" (PDF) (in Russian). Retrieved 2009-04-17.

- ↑ Staff writer (December 24, 2005 – January 6, 2006). "The dying fish swims in water". The Economist. pp. 73–74.

- ↑ Viitso, Tiit-Rein: Finnic Affinity. Congressus Nonus Internationalis Fenno-Ugristarum I: Orationes plenariae & Orationes publicae. (Tartu 2000)

- ↑ Paul Ariste: Eesti rahva etnilisest ajaloost. Läänemere keelte kujunemine ja vanem arenemisjärk. Artikkeli kokoelma. Eesti Riiklik Kirjastus, 1956

- 1 2 3 Kuznetsova, Natalia; Markus, Elena; Mulinov, Mehmed (2015), "Finnic minorities of Ingria: The current sociolinguistic situation and its background", in Marten, H.; Rießler, M.; Saarikivi, J.; et al., Cultural and linguistic minorities in the Russian Federation and the European Union, Multilingual Education, 13, Berlin: Springer, pp. 150–151, ISBN 978-3-319-10454-6, retrieved 2015-03-25

- ↑ The Uralic languages By Daniel Mario Abondolo

- 1 2 Heinsoo, Heinike; Kuusk, Margit (2011). "Neo-renaissance and revitalization of Votic — who cares?" (pdf). Eesti ja soome-ugri keeleteaduse ajakiri. ISSN 2228-1339. Retrieved 2014-09-22.

- ↑ Jokipii, Mauno: "Itämerensuomalaiset, Heimokansojen historiaa ja kohtaloita". Jyväskylä: Atena kustannus Oy, 1995. ISBN 951-9362-80-0 (in Finnish)

- ↑ Kallio, Petri (2014), "The Diversification of Proto-Finnic", in Frog; Ahola, Joonas; Tolley, Clive, Fibula, Fabula, Fact. The Viking Age in Finland, Studia Fennica Historica, 18, Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, ISBN 978-952-222-603-7

- ↑ http://www.kirj.ee/public/va_lu/ling-2006-1-1.pdf

Further reading

- Ariste, Paul (1968). A Grammar of the Votic Language. Bloomington: Indiana University. ISBN 978-0-87750-024-7.

- Kettunen, Lauri (1915). Vatjan kielen äännehistoria. Suomalaisen kirjallisuuden seura.

External links

| Votic language test of Wikipedia at Wikimedia Incubator |

| Wikiversity has learning resources about Grammar of Votian dialects |

- Votian at Indigenous Minority Languages of Russia

- Virtual Votia

- The Red Book of the Peoples of the Russian Empire

- Classification of Votian dialects at wikiversity

- Чернявский В. М. Vaďďa ceeli. Izeõpõttaja / Водский язык. Самоучитель.