Volunteer Training Corps

| Volunteer Training Corps | |

|---|---|

|

Proficiency Badge of the Volunteer Training Corps, depicting the war goddess Bellona | |

| Active | September 1914 – December 1918 |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Role | Defence from invasion |

| Disbanded | January 1920 |

The Volunteer Training Corps was a voluntary home defence militia in the United Kingdom during World War I.

Early development

After war had been declared in August 1914, there was a popular demand for a means of service for those men who were over military age or those with business or family commitments which made it difficult for them to volunteer for the armed services. At this stage in the war, Britain relied entirely on a voluntary system of enlistment and many men still held to the Victorian principle that it was the task of professional troops to fight a war whilst voluntary militias provided for home defence.[1] Combined with the perceived risk of a German invasion, this resulted in the spontaneous formation of illegal "town guards" and volunteer defence associations around the country, often organised by former Regular Army or Volunteer Force officers. The government was suspicious of this movement, seeing it as potentially diverting men from volunteering for the armed services. The enthusiasm was, however, unstoppable; by September 1914, a central committee had been formed and on 19 November 1914, a renamed Central Association of Volunteer Training Corps was recognised by the War Office.[2] Lord Desborough became the President of the Association and General Sir O'Moore Creagh VC was appointed the Military Advisor.[3]

Official recognition

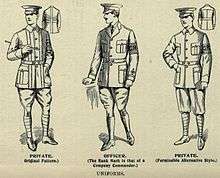

Although the Central Association had been officially recognized, the local Volunteer Training Corps were not. Units had to be financially self-supporting and members had to provide their own uniforms, which could not be khaki; the Association recommended Lovat green. All members were required to wear a red brassard or arm band, bearing the letters "GR" for Georgius Rex (i.e. the then sovereign, King George V).[4] No weapons or equipment were provided from public funds, although local Territorial Army Associations were asked to supply a few "DP" rifles, which were dummy weapons intended for "Drill Purposes".[5] The volunteers therefore had to purchase their own weapons and ammunition - typically Martini Enfield carbines and rifles. Membership of the Corps was only open to those who had "genuine reasons" for not enlisting in the regular armed forces although the list of exempted occupations was very wide and the CAVTC interpreted this as including those responsible for widowed mothers, unmarried sisters and those running small businesses.

Local VTCs soon grouped together to form county Volunteer Regiments. In October 1915, the Marquess of Lincolnshire attempted to give the Volunteers legal status by means of a private member's bill in the House of Lords, but it ran out of parliamentary time. However, MPs discovered that the Volunteer Act 1863 had never been repealed and the VTC Battalions legally became Volunteer Regiments in April 1916 as part of a new 'Volunteer Force'. Eventually they were allowed to wear khaki and equipment began to be officially supplied. In July 1918, the War Office decided to include the VTC Battalions into the County Infantry Regiment system, and they became numbered "Volunteer" battalions of their local regiment.[6] With the introduction of conscription in 1916, came the power of the Military Service Tribunals to order men to join the VTC; however, the clause in the 1863 act which allowed resignation after fourteen days' notice initially made this unenforceable, so a Volunteer Act 1916 was passed which obliged members to remain in the Corps until the end of the war. By February 1918, there were 285,000 Volunteers, 101,000 of whom had been directed to the Corps by the Tribunals.[7]

Equipment, training and role

During 1917, P.14 Enfield Rifles began to be issued, followed by Hotchkiss Mk I machine guns.[5] The Corps trained in drill and, if the equipment was available, use of the rifle. In case of a German invasion, battalions were tasked with roles such as line of communication defence and forming the garrison of major towns; 42 battalions were to defend London. Volunteers undertook a wide range of other tasks including; guarding vulnerable points, munitions handling, digging anti-invasion defence lines, assisting with harvesting, fire fighting and transport for wounded soldiers. In north Worcestershire some units helped to man anti-aircraft guns ringing Birmingham.[8] In 1918, when there was an acute shortage of manpower because of the German spring offensive, c.7,000 Volunteers undertook three-month coast defence duties in East Anglia. The force was sometimes ridiculed by the public; there were jokes that the "GR" on their armbands stood for "George's Wrecks", "Grandpa's Regiment", "Genuine Relics",[9] "Gorgeous Wrecks" or "Government Rejects".[10]

The Easter Rising in Dublin

The only time that Volunteer Training Corps men were engaged in actual combat, was in the Easter Rising in Dublin starting on Easter Monday, 24 April 1916. Some 120 members of the 1st (Dublin) Battalion, Associated Volunteer Training Corps were returning from field exercises at Ticknock, when they heard news of the uprising. The commanding officer, Major Harris, decided to march to Beggars Bush Barracks. They carried rifles but were without ammunition or bayonets. They were fired on by a party of Irish Volunteers from a railway bridge. Part of the VTC force entered the barracks by the front gate, others made their way to the rear and scaled the wall. About 40 men at the rear of the column were pinned down by fire from surrounding houses and four were killed, including the first-class cricketer, Francis Browning, who had been second-in-command. The VTC men then assisted the small garrison of regular soldiers to hold the barracks for eight days.[11] In total, five members of the battalion were killed and seven wounded.[12]

Disbandment

The Volunteer Training Corps was suspended in December 1918, and officially disbanded in January 1920, with the exception of the Volunteer Motor Corps which was retained until April 1921 in case of civil disorder.[13]

See also

References

- ↑ Osborne, John (Jan 1988). "Defining their own patriotism: British Volunteer Training Corps in the First World War". Journal of Contemporary History.

- ↑ Ian Frederick William Beckett, A Nation in Arms: A Social Study of the British Army in the First World War, Manchester University Press 1985, ISBN 0-7190-1737-8 (p. 15)

- ↑ Blake, J. P. (editor), The Official Regulations for Volunteer Training Corps and for County Volunteer Organisations (England and Wales) The Central Association Volunteer Training Corps 1916 (p. 10)

- ↑ H. Keatley Moore and W.C. Berwick Sayers (Editors), Croydon and the Great War Croydon Central Library 1920 (pp. 104–5)

- 1 2 King's Own Royal Regiment Museum - 1st & 2nd Volunteer Battalions, King’s Own Royal Lancaster Regiment (Volunteer Training Corps) by H. H. Owtram, April 1934

- ↑ Kent War Memorials Transcription Project - Reports - West Kent Units

- ↑ Beckett, A Nation in Arms, pp. 15–16.

- ↑ Atkin, Malcolm. "Introduction to the Worcestershire Volunteer Force". Worcestershire VTC & Volunteer Force.

- ↑ Frederick William Beckett, The Amateur Military Tradition, 1558-1945, Manchester University Press 1991, (p. 240) ISBN 978-0-7190-2912-7.

- ↑ A Dictionary of Slang and Unconventional English by Eric Partridge (8th edition, edited by Paul Beale), pp. 490–1.

- ↑ Sinn Fein Rebellion handbook, Easter, 1916. The Irish Times, 1917 (p. 22)

- ↑ Irish Times (p.58)

- ↑ Beckett, A Nation in Arms, p. 16.

External links

- British Pathé newsreel of the Pharmacists' VTC being inspected by Brigadier General Bridgeman in a London park in 1916

- British Pathé newsreel of the City of London VTC parading past the Lord Mayor at Mansion House in 1916

- British Pathé newsreel: "The King Calls For Volunteers", showing VTC men digging trenches and rigging a barbed wire entanglement for home defence in 1917

- A red VTC brassard bearing the letters "GR" in black, preserved at the Imperial War Museum, London