Vivarium

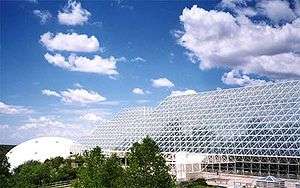

A vivarium (Latin, literally for "place of life"; plural: vivaria or vivariums) is an area, usually enclosed, for keeping and raising animals or plants for observation or research. Often, a portion of the ecosystem for a particular species is simulated on a smaller scale, with controls for environmental conditions.

A vivarium may be small enough to sit on a desk or table, such as a terrarium or an aquarium, or may be a very large structure, possibly outdoors. Large vivaria, particularly those holding organisms capable of flight, typically include some sort of a dual-door mechanism such as a sally port for entry and exit, so that the outer door can be closed to prevent escape before the inner door is opened.

In modern literature, the word was not heavily used until a publication called "Vivarium", the first of its kind, was created by Phillipe De Vosjoli in San Diego, California to share information about the keeping of reptiles, amphibians and other terrestrial animals in captivity.

Flora and fauna

There are various forms of vivarium, including:

- Aquarium, simulating a water habitat; for instance a river, lake or sea; but only the submerged area of these natural habitats. Plants in the water will use some nitrogen present within the system, and will provide areas for organisms to hide and forage.

- Oceanarium, containing larger ocean-dwelling fish and mammals, such as sharks or dolphins.

- Insectarium, containing insects, arachnids, and other similar arthropods.

- Formicarium, with species of ants.

- Terrarium, simulating a dry habitat, for instance desert or savannah. A terrarium can also be formed to create a temperate woodland habitat, and even a jungle-like habitat. This can be created with pebbles, leaf litter and soil. By misting the terrarium, a natural water cycle occurs within the environment by condensation forming on the lid causing precipitation. Many kinds of plants are suitable for these habitats, including bromeliads, African violets and Crassulaceae. Animals commonly held for observation include reptiles, amphibians, insects, spiders, scorpions and small birds.

- Paludarium, a semi-aquatic enclosure simulating a rain forest, swamp or other wetland environment. It also can be seen as an aquarium interconnected with a terrarium, having both the underwater area as well as the shore.

- Penguinarium, containing penguins.

- Riparium, a new kind of planted aquarium system that recreates the wet habitats found along the edges of lakes, rivers, ponds and streams. This zone hosts marginal plants, which are rooted in the saturated soil at the edge of the water, but hold their leaves up in the air. Unlike a paludarium however, ripariums do not have a significant land portion, making them unsuitable for most amphibians. Instead, they utilize specialized planters which either hang onto the sides of the tank or float on the water's surface.

- Herpetarium, containing various species of reptiles and amphibians. Herpetariums may fall under another category of vivariums, depending on the natural habitat of the species being kept.

Size and materials

A vivarium is usually made from clear container (often plastic or glass). Unless it is an aquarium, it does not need to withstand the pressure of water, so it can also be made out of wood or metal, with at least one transparent side. Modern vivariums are sometimes constructed from epoxy-coated plywood and fitted with sliding glass doors. Coating the inside of a plywood vivarium helps to retain the natural effect of the environment. Epoxy-coated plywood vivariums retain heat better than glass or plastic enclosures and are able to withstand high degrees of humidity. They may be cubical, spherical, cuboidal, or other shapes. The choice of materials depends on the desired size and weight of the entire ensemble, resistance to high humidity, the cost and the desired quality.

The floor of a vivarium must have sufficient surface area for the species living inside. The height can also be important for the larger plants, climbing plants, or for tree climbing animal species. The width must be great enough to create the sensation of depth, both for the pleasure of the spectator and the good of the species inside.

The most commonly used substrates are: common soil, small pebbles, sand, peat, chips of various trees, wood mulch, vegetable fibres (of coconut for example), or a combination of these. The choice of the substrate depends on the needs of the plants or of the animals, moisture, the risks involved and aesthetic aspects. Sterile vivariums, sometimes used to ensure high levels of hygiene (especially during quarantine periods), generally have very straightforward, easily removable substrates such as paper tissue, wood chips and even newspaper. Typically, a low-nutrient, high-drainage substrate is placed on top of a false bottom or layer of LECA or stones, which retains humidity without saturating the substrate surface.

Environmental controls

Lighting

A lighting system is necessary, always adapted to the requirements of the animal and plant species. For example, certain reptiles in their natural environment need to heat themselves by the sun, so various bulbs may be necessary to simulate this in a terrarium.

Also, certain plants or diurnal animals need a source of UV to help synthesize Vitamin D and assimilate calcium. Such UV can be provided by specialized fluorescent tubes or daylight bulbs, which recreate the reptiles' natural environment and emit a more natural sunlight effect compared to the blue glow of a fluorescent tube.

A day/night regulator might be needed to simulate with accuracy the alternation of light and dark periods. The duration of the simulated day and night depends on the conditions in the natural habitat of the species and the season desired.

Temperature

The temperature can be a very important parameter for species that cannot adapt to other conditions than those found in their natural habitat.

Heating can be provided by several means, all of which are usually controlled by a thermostat: heating lamps or infrared lamps, hot plates and heat mats, providing heat at the base or sides of a terrarium, heating cords or heat mats placed beneath the substrate, heat rocks, or more complex equipment generating or producing hot air to the inside of the vivarium.

Similar to lighting, a decrease in temperature might be needed for the simulated night periods, thus keeping living species healthy. Such variation need to be coherent to those found in the natural habitats of the species. Thermo-control systems are often used to regulate light cycles and heating, as well as humidity (coupled to built-in misting or rain systems). Light-dependent resistors or photo-diodes connected to the lighting are frequently used to simulate daytime, evening and nighttime light cycles, as well as timers to switch lighting and heating on and off when necessary.

Humidity

Many plants and animals have quite limited tolerance to the variation of moisture.[1]

The regulation of humidity can be done by several means: regular water pulverization, water evaporation inside (from a basin, or circulation of water), or automated pulverization systems and humidifiers.

Ventilation and openings

Access inside the vivarium is required for the purpose of maintenance, to take care of the plants and animals, or for the addition and withdrawal of food. In the case of some animals, a frontal opening is preferable because accessing a vivarium from the top is associated by some species with the presence of predators and can therefore cause unnecessary stress.

Ventilation is not just important for circulating air, but also for preventing the growth of mold and development and spread of harmful bacteria. This is especially important in warm, humid vivariums. The traditional method consists of placing a suction fan (or ventilation slits) at a low level and another exhaust fan at a higher level, which allows the continual circulation of fresh air.

Gallery

.jpg) Butterfly vivarium or Insect home, Henry Noel, ca. 1858.

Butterfly vivarium or Insect home, Henry Noel, ca. 1858. Two large glass terrariums with plants

Two large glass terrariums with plants

Vivarium with epoxy-coated plywood walls.

Vivarium with epoxy-coated plywood walls.- Binturong (Arctictis binturong) in vivarium Darmstadt, Hessen, Germany.

See also

- Aquascaping

- Biome

- Biosphere

- Closed ecological system

- Ecosphere

- Ecosystem

- Wardian case

- Winogradsky column

- Micro landschaft

- Ex situ conservation

- Botanical garden

- Barn

- Stable

- Greenhouse

References

- ↑ "The Fever Trail" - Mark Honigsbaum (MacMillan 2001)